Victory: The Triumphant Gay Revolution - Linda Hirshman (2012)

Chapter 2. Red in Bed: It Takes a Communist to Recognize Gay Oppression

It’s been a long time since many Americans looked up to Joseph Stalin. But from the time gay-movement founder Harry Hay joined the Communist Party in 1934 to his departure sixteen years later, he did. Hay even got married to satisfy Uncle Joe, which was a real tribute, because Hay had been an active homosexual since he was nine.

Stalin didn’t much like homosexuals. Although the Bolsheviks decriminalized homosexual acts in 1918, sixteen years later, the dictator acted personally to reverse that liberal development. After 1934, the Soviets treated homosexuality as the decadent product of bourgeois culture, punishable by years at hard labor.

When Harry Met Willy

Hay the homosexual Communist was a traitor to his class. His father was a successful mining engineer and his mother was born to a mining family with a long military tradition and exalted social contacts. Hay never lost the willful, patrician manner he learned as a boy. Even cross-dressing decades later, he always wore a proper string of pearls.

When Harry was four, his father had a bad industrial accident and had to retire. The family settled on some land he bought in California. Not having a large industrial-mining operation to boss around wasn’t great for Harry’s father, whose disposition quickly led to conflict with his strong-willed, smart offspring. For years, Harry’s father whipped him to cure him of being … left-handed. One night, Big Harry said something at dinner about Egypt that contradicted what his nine-year-old son had been reading. The kid disagreed and his father dragged him off to the garage for a whipping with a razor strop followed by bed without dinner. Some hours later, Harry’s mother crept into his room with a tray of supper to find her unrepentant son, surrounded by his reference books, looking up quotations on being true to yourself no matter what.

When Harry got to high school, he added to his father’s woes by taking a deep interest in drama class. Although their son grew tall early in youth and had a Californian’s love of hiking and the out-of-doors, the senior Hays, perhaps sensing something, sent him off to his cousin’s farm to “toughen him up.” Unbeknownst to Harry’s establishment family, several of their field hands were members of the super lefty union, the Industrial Workers of the World (“Wobblies”). Soon Harry was riding on the hay wagon with copies of Marx’s “Wage Labor and Capital.” Bringing in the hay with the workers of the world quickly captured the idealistic young man’s attention.

After a year at Stanford, Harry left school for Los Angeles to try to become an actor. He found a left-leaning community there, too. Apparently California Communists didn’t take quite as hard a line on sexual deviance as the Muscovite branch, because Harry was recruited to the party by a lover, Will Geer. Geer, a homosexual and lifelong radical, later immortalized as the all-American Grandpa Walton on The Waltons television series, took Hay to San Francisco during the General Strike of 1934. While they were there, the state militia killed two of the strikers and sent eighty or more to the hospital. There was a big political funeral, and young Hay was hooked.

Communism and the Homosexual

Some of the elements of revolution were there before Harry Hay appeared on the scene. There were crowds. Sometimes the benches in New York’s Central Park were so crowded with gay men, cruising and schmoozing, that there was no room for anyone else to sit down. Every time there was a gay ball, there was a crowd. When the performer Beatrice Lillie (kind of an early Judy Garland) appeared, there seemed to be no one but gays in the audience. They were subjected to a universe of indignities. Police were spying on them in the subway bathrooms and throwing them into jail on the easily provable charge of disorderly conduct. But they had money to spend. When apartment houses started to spring up in New York, gay men moved into them. They gave great parties—liquor flowed freely throughout Prohibition. They went to Europe on great steamer lines. They never missed a play or a concert.

When like-minded people come together, sometimes they are liberated to act to release their underlying feelings in ways they would never do alone. Terrified French aristocrats called it madness. But as revolution became more common, theorists realized that crowds are actually a convergence of like-minded individuals. Gathering on the streets, abused by the dominant society, tied by bonds of desire, and possessed of resources and a secret language, the gay men of New York, San Francisco, and Los Angeles were a crowd. But crowds do not always or even usually produce a social movement. For that to happen, a community must develop a rebellious state of mind, what the theorists call oppositional consciousness. The crowd of the gay community lacked pretty much all the possible social-movement triggers. It had no ideology, no organizational strategy, and no leader. Until Harry Hay.

Early in his dual career as a homosexual and a Communist, Hay figured out that the revolutionary tenets of Communism could be applied to homosexuals. When he made a tentative suggestion to Geer that they form a “team of brothers” along the communist model, Geer replied that the theater was enough of a homosexual brotherhood. The theatrical brotherhood doesn’t talk politics, Hay objected. There was nothing political to discuss, Geer said.

Technically, Geer was right. With communist glasses on, what we now call identity politics, like the homosexual association Hay suggested, were indeed invisible. Marxism teaches that only economic relationships matter. Once the relationships of class are straightened out, the other oppressions will disappear in due course. The oppression experienced by homosexuals, or blacks and women, simply does not matter in the inexorable march to the triumph of the proletariat. When Hay’s homosexual commitments finally overwhelmed his communist loyalties in 1950, he was graciously allowed to resign from the party, his political family for sixteen years. And when the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) came after him anyway, the lawyers who usually defended party members left him to depend on the kindness of strangers.

But whether the party liked it or not, communist theory, filtered through the fertile brain of Harry Hay, did indeed apply to the situation of homosexuals. Hay would find a support for this thinking in, of all things, Stalin’s own writings. Despite identity politics’ invisibility to Marx, Stalin was moved to address the subject, because, as the Communists rose to power in the early twentieth century, they had to compete with national-liberation movements, like the ones threatening to break up the Austrian and Russian Empires. In 1913, Stalin wrote a description of people who qualified as “nations” for purposes of self-determination. A nation is a historically stable community of people, according to his definition. It has a common vernacular language. It occupies a single piece of territory. It has an integrated, coherent economy. It possesses a community of psychological makeup (a folk-psychology, or national character). And it is “a historical category belonging to a definite epoch, the epoch of rising capita1ism.” Despite Stalin’s rather narrow definition of a nation, under his tutelage, Communism did make common cause with some insurgent ethnic groups.

Hay considered his appropriation of the homophobic Stalin’s writing to be his finest act. Homosexuals did not exactly fit Stalin’s description of a suppressed nation. True, in the epoch of rising American industrial capitalism, gay and lesbian people gathered in large cities and colonized similar pieces of territory. They had developed a common vernacular language. They had something of a coherent economy. And they had a community of psychological makeup. Hay believed that “language and culture were enough to make a minority.” But its sites were scattered, its economic institutions were primitive at best, and it encompassed a wide range of psychological attitudes. Conceiving “Gay New York” as a colonial nation in revolt was a stretch to say the least.

Hay had some help making the connection. In 1930, after the Communists had become a serious international force, the body charged with giving direction to Communist parties everywhere—the Comintern—put out a flexible definition of “nationhood.” The Communists wanted to attack America in its treatment of its “12 million Negroes.” American Negroes, a historically stable community with its own economy, vernacular language, and psychology, were concentrated in the Black Belt of the American South. The Comintern and the American Communist Party first advocated the establishment of an independent Negro state there. The aforesaid Negroes, however, had already begun a substantial migration that would scatter them throughout the North. The Communists wound up supporting Negro struggle everywhere it occurred. And they made a difference: when the Communist Party took up the cause of the Scottsboro boys, nine black youths arrested and eight convicted of raping a white woman in Alabama in 1931, they gained a foothold in the emerging movement, much to the chagrin of the mainstream NAACP.

Once the Communist ideology machine recognized the special place of the oppressed Negro minority in the human liberation project, the way was opened for other American identity groups, such as Hay’s team of brothers, to use the idea of a national minority for their own liberation. When Hay joined the Communist Party in 1934, then, the ideas that he would use for the liberation of homosexuals—collective identity and moral claim to equality—were in place. For the next fifteen years he would devote himself to mastering them.

Better Red Than Bed

There’s a fabulous head shot of Harry Hay in the thirties, with a natty ascot tie and a flat cap covering his premature bald spot. Level, intense gaze and cleft chin: it’s understandable that his early years as a card-carrying Communist involved as much rolling in the hay as remembering the Haymarket. After comrade Will Geer, Harry had a fling with a Brazilian FBI stooge and spent months in the arms of a seventeen-year-old jail bait. All the while he was screwing around, he went to ideology school at the various Communist Party centers. But no matter how Harry tried, he could not reconcile his two worlds. None of his homosexual lovers was the least bit interested in politics. When he came to a gay Halloween party one year around 1936 dressed as the “demise of Fascism,” no one could figure out what his costume meant.

Harry finally gave up on his conflicting passions after his most deeply felt homosexual love affair went south. His beloved, Stanley Taggart, had appeared one night at the stage door of a play Harry was in, Clean Beds. Six blissful months later, Taggart’s mother, the matriarch of the Kansas Taggarts, took her wayward son to England for a spell of reparative therapy. The next thing Harry knew he was opening a wedding announcement. When Taggart returned a year later—repentant, but uninterested in politics and, indeed, still dragging his wife after him, Harry finally confronted the gulf between his life in the closeted gay world and his political commitments. His internist referred him to a psychiatrist—the only time in his ninety-year life he ever saw one—who suggested that a mannish girl might be just as good as the girly men he seemed to prefer. Six months later, in 1938, Harry Hay married Jewish fellow traveler Anita Platky and told his local party officials that his wandering days were over. They adopted two children. He went to work at the Leahy boiler factory in Los Angeles to support the family.

Before the marriage was a year old, Hay was cruising in Los Angeles’s Lafayette Park. But during his decade as a purported heterosexual married Communist, Hay devoted himself to learning and teaching every aspect of Marxist thought. He taught political economy, he taught how to run a meeting, and he taught courses on imperialism and, his great love, “Music, the Barometer of the Class Struggle.”

Bachelors for Wallace

Just as Hay was putting the finishing touches on his music syllabus in 1948, Bill Lewis, one of the gay men at the Leahy factory, brought his friend “Chuck” to lunch. Chuck was visiting from DC, where he was one of the top secretaries at the Department of State, and Lewis thought Hay should hear what he had to say. “Everyone in his department was terrified,” Chuck reported to Hay. A “dreamboat” named Andrew had shown up at State one day from an assignment somewhere else and the lucky guys who slept with him were called in and lost their jobs.

In 1947 President Harry S. Truman had already set up the first security investigations in the executive branch. In February 1950, Senator Joseph McCarthy would tell the good citizens of Wheeling, West Virginia, that he had a list of 205 card-carrying Communists who were working in the State Department. A few months after the Wheeling speech, the State Department’s deputy undersecretary for administration, John Peurifoy, went to Congress to represent the department in a security investigation and proudly announced that, although there were no Communists in the State Department, the department’s security apparatus had unearthed ninety-one homosexuals, who had been separated from their posts.

Red and lavender, the scares began.

As usual with Hay, the warning about the dangers of trying to organize homosexuals had the opposite effect. “The country, it seemed to me,” he remembered thinking, “was beginning to move toward fascism and McCarthyism; the Jews wouldn’t be used as a scapegoat this time—the painful example of Germany was still too clear to us. The black organizations were already pretty successfully looking out for their interests. It was obvious McCarthy was setting up the pattern for a new scapegoat, and it was going to be us—Gays. We had to organize, we had to move, we had to get started.”

A few weeks after his friend warned him about the dangerous new order in Washington, Hay went to a signing for the new Progressive Party. The party was fielding FDR’s very liberal ex-vice president, Henry Wallace, as a third-party candidate for president. Hay was pleasantly surprised at how many people added their names to his candidacy petitions. At dinner on the night of the signing, his wife, Anita Platky, who’d had just about enough of the Communist Party and her homosexual husband, was singularly uninterested in his Progressive Party—and in the party he was going to after they finished eating. Just as well: the invitation for the evening came from the handsome guy Harry had picked up cruising one of Los Angeles’s gay parks.

When Hay walked into the party near the University of Southern California that night, he found a gathering of seminary and music students all of whom seemed to be gay. A young seminary student from France opened the conversation. Had Hay heard of the Kinsey Report, Sexual Behavior in the Human Male, published just months before in 1948? In this first purportedly scientific study of human sexual behavior, zoologist Alfred Kinsey had reported that 37 percent of American men had had at least one homosexual experience. Hay lit up: Kinsey’s report, contested though it was, suggested a substantial population of “brothers.” If the Democratic Party could spawn Wallace’s Progressive candidacy, what else might be possible?

As the beer flowed, Hay played out how such a group might organize. They could call their organization Bachelors for Wallace. In the midst of relentless mockery (guests proposed campy, derisive names like Fruits for Wallace), Hay laid down most of the elements of a social movement in the liberal state. Homosexuals might organize gay votes for the liberal presidential candidate, participating in collective self-governance. Then, in a classic political move, they would cash out their efforts and their votes, demanding a plank in the party platform. Their platform would include another hallmark of the liberal state—the right to be left alone—in the form of a “privacy” plank, which was code talk for letting them engage in sodomy without putting them in jail. But Hay didn’t stop there; as would characterize the gay movement whenever it succeeded, he demanded respect. Maybe someone of serious social standing might take up their cause and speak for them, dare they think it, at the Democratic National Convention? When he got home, he wrote it up as “International Bachelors Fraternal Order (sometimes referred to as ‘Bachelors Anonymous’).”

The next day Hay called the guy who gave the party and got names and phone numbers of the other attendees. But all anyone wanted to talk about next morning was how hung over they were. From 1948 to 1950, as homosexuals were fired or driven from the service of their government by the score, and Peurifoy’s “ninety-one” came to be smarmy code talk for the love that dare not speak its name, Hay could not find one person to join him in his Bachelors Anonymous.

Hay, always thinking, took the time to figure out a plan of action and a framework derived from his long-held views about oppressed minorities. Unlike the other two great movements, which were identified by race or sex, first, “What we had to do was to find out who we were.” Once that big task was behind them, “What we were for would follow. I realized that we had been very contributive [sic] in various ways over the millennia, and I felt that we could return to being contributive again.” Homosexuals didn’t have their own land or economy, but they had a unique culture and a kind of language. He set out the crucial demand that has fueled and refueled the gay revolution ever since: to “be respected for our differences not for our samenesses to heterosexuals. Our organization would renegotiate the place of our minority into the majority.”

As with all identity movements, “who we were” would prove to be much fuzzier than the orderly Hay anticipated. At the very moment Hay was drafting his manifesto, a few male cross-dressers gathered in clubs like Los Angeles’s Hose and Heels, whose founder, Charles, would one day become Virginia. George Jorgensen went to Denmark for sex-reassignment surgery and returned transformed as the camera-ready Christine. Who were we? Hay himself liked to dress in women’s clothing.

Still, however permeable the boundaries, through Hay, the gay movement is rooted in a concept of identity that had flared up only once before, in black separatist Marcus Garvey’s short-lived Universal Negro Improvement Association: not the same, but equally to be respected. Recognizing the distinctive gay minority with its own language and culture was crucial to the success of the movement. Any other starting place would have been a lie and likely to fail. Worse, if gays based their claim to proper treatment on sameness to nongays, they would have been conceding that their difference was a drawback or a failing. Decades later, scholars would call this refusal of minority cultures to evolve into heterosexual white Protestant suburban Americans “beyond the melting pot,” after Nathan Glazer and Daniel P. Moynihan’s book published in 1970. Stalin’s definition of a minority, derived from the indigestible ethnic minorities—Hungarians, Serbs, Georgians—of the waning days of the Russian and Hapsburg Empires, would find a whole new life in the anonymous bachelors of Southern California.

The Red Golden Age of the Mattachine Society

On July 6, 1950, one of the products of the old Hapsburg Empire, Viennese Jewish refugee Rudi Gernreich, arrived as usual for a rehearsal of his dance performance at Los Angeles’s avant-garde Lester Horton Dance Company. Family man Harry Hay was there watching his talented dancer daughter, Hannah. Across a crowded rehearsal room, he spotted the face of the gorgeous Gernreich, who would one day be one of America’s leading avant-garde clothing designers, dressed, as usual, in his sexy black turtleneck and trousers. Harry could not believe Rudi was staring back. They arranged to meet.

It’s hard to take the sex out of homosexual. Of course, no human being is defined by what he or she does, as one of my gay friends says, twice a week for fifteen minutes if they’re lucky. But the gay revolution was both strengthened and weakened by the sexual connections that were possible among its makers. An amazing amount of the gay revolution turns on those ties. Hay brought a copy of his Bachelors Anonymous manifesto to his first date with Gernreich. “We were in love with each other and each other’s ideas,” Hay remembers.

Before Gernreich had left Vienna in the nick of time in 1938, he had known about the German Magnus Hirschfeld’s Institute for Sexual Research, a pioneering effort to identify the extent of homosexuality and study the subject scientifically. He thought the Nazis identified homosexuals for prosecution from the records they found there and was suitably respectful of the dangers in the McCarthyite prosecutions that were now well under way.

Harry and Rudi went to a Malibu beach famously colonized by gay bathers and got five hundred signatures on a petition to pull the United States out of the Korean War. But not a single peacenik would agree to come to a covert meeting to discuss Kinsey’s new findings about social deviancy. Hay was powerfully disappointed. Homosexuals were willing to take on the entire United States military-industrial complex but not to discuss Sexual Behavior in the Human Male?

Understanding why people would be reluctant to come forward, Rudi was undeterred. You’re teaching progressive music classes, Gernreich observed a few months later in November. Why not try that little blond guy you think is homosexual? Nervously, Hay proffered a copy of his manifesto to his student, Bob Hull, at the next class. Shortly after that, Hull phoned to ask if he and a friend could come to Hay’s to discuss what he had provided. As Hay and Gernreich anxiously waited, they caught sight of Hull’s roommate, the very Midwestern Chuck Rowland, with his buck teeth and rimless glasses, running up the hill to the house waving the thing “like a flag.” “I could have written this myself” were Rowland’s first words. Four gay men—three Communists and one closeted would-be fashion icon—the gay movement in America was officially launched. Another sexual connection brought the fifth founder, Hull’s then-lover, Dale Jennings. After a stint as a carnival roustabout, the macho Jennings was writing for a living.

Hay may have read Robert Duncan’s call to homosexuals to abandon the destructive campy bar talk, because he, with Rowland, pushed hard for the new organization to develop “an ethical homosexual culture.” They wanted to discuss how the gay culture could enable gay people to lead well-adjusted, wholesome, and socially productive lives. For a while, Harry and Rudi and Chuck and Bob and Dale and a shifting group of others just talked about their lives, finding comfort in their familiarity and creating their own normalcy through shared experience. They called their relationships “homophile”—loving friendship of men—to replace the clinically tainted term “homosexual.”

At first the group took the name Society of Fools. From his extensive researches into the history of music, Hay knew that, in many European cultures, fools were more like jesters than crazies. They were privileged by their clownish disguise to speak truth to power. There were even societies of fools, revelers who used the ancient festivals—the Feast of Fools, which we now know as a range of prankish holidays from Halloween to April Fools’ Day—to mock the otherwise untouchable rulers of church and state. Hay concluded—not without support in the scholarship—that some of those societies known for a warlike dance, the mattasin, were called, in translation, the Mattachines. Mindful of the negative associations of “fools,” the group adopted the name Mattachine Society: masked revelers bearing a message of insurrection. Coincidentally, just before Hay’s bachelors organized themselves as revelers, gay men routinely had started calling each other “gay.” Unlike, say, “queer,” which had been the most common description, meaning, strange or not the norm, “gay” had a happy sound. By the fifties, “homosexuals” had made an important move to call themselves something positive.

Each of the original five Mattachines brought in their acquaintances. They even tried again with the antiwar closeted beach gays from the prior summer’s busted play. Within a year, the last two of the essential founders, and, fatefully, the first members without ties to the Communist Party—joined. When one of the newbies saw a copy of the Daily Worker on Bob Hull’s couch, he thought it was a joke.

Hay and the other founders recognized, crucially, that gay people had a mighty task of self-invention on their hands, because most people learn their values and form their consciousness in their heterosexual families. The Mattachines rejected what they considered the sick and perverse imitation by gays of heterosexual values, with their grounding in rigid gender roles. Thus, long before any modern feminist movement came on the scene, the first months of Mattachine meetings were devoted to what the groups of liberation-seeking women would later call “consciousness raising.”

Hay even had a theory for the structure of the organization: like the Communists and the Masons, another subversive group, the Mattachines would be organized in cells, called “guilds.” As the discussion groups flourished, the founders selected representatives from the bottom-level groups to join the guilds. Only the guild members knew the names of any other members of their own guild. Altogether, the guild members were the first level of governance. Had they attracted enough people, representatives from the guilds at the first level would come together to form the second level, and so on up a pyramid of increasing hierarchy until they reached the fifth level, which the founders assigned to themselves. Since they never attracted enough people to make it to the third and forth levels, the pyramid mostly consisted of discussion groups and their representatives in first-level guilds. The founders continued to run the show.

The Mattachine Society manifestly tapped into a latent social need. Within a year or two of the founding, there were discussion groups of as many as 150 people and a first level of guilds populated by handpicked representatives. Wow! The beautiful Rudi returned from an abortive effort to start his designing career in New York. Harry divorced his wife and resigned from the Communist Party. It was 1952. He was at the top of his game.

The People v. Dale Jennings

Mattachine founder Dale Jennings, on the other hand, was feeling like shit. He and his longtime lover, Bob Hull, had just broken up. Dale decided to run over to Westlake Park and see who was around. There was a man in the toilet. I’ll follow you home, the man said; can you make me a cup of coffee? When they got to Dale’s home, Dale was going to the kitchen when he noticed the toilet guy fussing with his window blind. One minute later, he heard knocking and saw the flash of handcuffs as another policeman came through his door.

At two a.m., Harry Hay’s phone rang. Fifty dollars’ bail later, Hay and Jennings were sitting at the Brown Derby eating breakfast. Hay had one of his moments. “We’re going to make an issue of this thing. We’ll say you are homosexual but the cop is lying.”

Hay called an emergency meeting of the Mattachine founders for that very night and made an impassioned plea for the group to “press the issue of oppression.” Rudi Gernreich, who was always a little different from the rest, had already fought back against similar police tactics, insisting on going to trial when he got caught years earlier. To his amazement, Gernreich was convicted. But not discouraged.

Perhaps emboldened by the unexpected success of their burgeoning organization, everyone agreed that Jennings should fight. The young Mattachine group created a pseudonym for his defense: Citizens Committee to Outlaw Entrapment. The committee hired one of the leading liberal lawyers in Southern California, a straight criminal defense and labor attorney, George Shibley, and prepared to go to trial.

When the establishment media would not carry news of the trial, the committee summoned the gay community into political action. They cranked out leaflets, “Are You Left-Handed?” and the unprecedented “Anonymous Call to Arms.” Claiming common cause with the nascent civil rights movement, the gay pamphleteers of 1952 argued that police brutality against minorities was also being applied to them. They distributed their propaganda at gay beaches and bars, in the bathrooms, benches, and bus stops of gay LA. They even got supermarket clerks to put their fliers in their gay clients’ grocery bags. They held dances and beach parties and raised thousands of dollars to pay their lawyer and get transcripts for distribution. For at least six decades, American cities, including Los Angeles, had included a minority community with its own coded language, traditions and geography, bars, baths, beaches, and balls. The Mattachine Society and the Jennings trial offered the gay community, at last, politics. In two years, Hay’s efforts had gone from talk at a “bachelor” party that no one could remember the next morning to a major civil rights initiative.

And they won! Shibley opened by arguing that the only true perverts in the courtroom were the cruising policemen intent upon entrapment. Forty hours into deliberation, the jury declared itself hung, because one juror wouldn’t agree with the other eleven that Jennings should be acquitted. “Victory!” crowed the pamphlet the committee sent out when the establishment media refused to run a word about the unprecedented decision.

Many-parented Victory also had a thousand sons. Gay Angeleno Dorr Legg was working in his city-planning job as usual when one of his coworkers walked up to his desk. “Have you heard about the guy here who has fought the police and won?” “No.” “Well, he has, and there’s an organization about it.” One year after Jennings’s trial, two thousand people were talking about homosexuality at a hundred Mattachine-sponsored discussion groups from San Diego to San Bernardino. A San Francisco peacenik, Gerry Brissette, started a San Francisco chapter.

As the chapters proliferated, they became more diverse. The San Francisco chapter actually attracted female members in noticeable numbers, while the chapter around UCLA undertook a project of scholarly research. Mattachine applied to incorporate as a foundation with Hay’s matronly mother, Margaret Neall Hay, as treasurer. They thought they could get heterosexual allies to support them with research and funding.

Fun-loving Martin Block, legendary for his female impersonation of a garden-club chair at the Mattachine meetings, nearly lost his fur piece at a meeting at Al Novick and Johnny Button’s house that spring. “I’m tired of talking,” Button blurted out. “I want to do something! Why don’t we start a magazine?” The first issue of ONE magazine (out of many, one), January 1953, was devoted to Jennings’s story. Soon the magazine had sales of two thousand copies a month and a circulation of many more. Fortunately, as it turned out, Jennings, Legg, and the other ONE editors organized the magazine separately from the Mattachine Society. The independent Jennings did not want to be bossed around by bossy Harry Hay.

The Mattachines were on a roll. When it came time for the elections for Los Angeles City Council early in 1953, they sent a questionnaire to each and every candidate, demanding to know their positions on questions of interest to the homophile organization, such as, what did the candidates think of police harassment of homosexuals and sex education in the public schools? It was the first time homosexuals in America tried to call their elected representatives to account. It was almost the last.

Better Dead Than Red

A few days later, the nascent activists opened their afternoon copies of the Los Angeles Mirror to read “Well, Medium and Rare,” a column about their “strange new pressure group” by the paper’s columnist Paul Coates. Now look who thinks they can hold their legislators to account, Coates crowed. He easily unearthed the unfortunate fact that Mattachine corporate lawyer Fred Snider had refused to answer questions from the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), invoking his Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination. Homosexuals had been “found to be risks in our State Department,” Coates reminded his readers and told the Mattachine members they had reason to worry about who was in their new club.

In hindsight, the confrontation was inevitable. While the Communist-inspired homosexual organization had been crowing about its victory before one Los Angeles criminal jury in the Jennings case, homosexuals and Communists were everywhere under fire. As Bill Lewis’s friend from State had warned Harry Hay in 1948, the search for Communists in American institutions had exploded across the American scene. HUAC, the FBI, the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee—actually headed for a time by the eponymous McCarthyite Senator Joseph McCarthy—were all issuing subpoenas, taking testimony, asking for names, and prosecuting for everything from treason to perjury. The foreign-policy establishment was a particular target for the red hunters, as some of their activities were a response to the victory of the Chinese Communists, an event inexplicable to some as anything but a product of American treason. “Who lost China?” became a watchword of their inquisition.

The search for traitors quickly turned to the institutions of American culture as the obvious place for undermining the great republic. HUAC was particularly feared in California; it had been investigating the Hollywood movie industry almost since 1947. (In an unfortunate coincidence, HUAC was holding hearings in LA when the Coates article appeared.) The government was somewhat constrained by the constitutional right against self-incrimination, and a lot of the people HUAC targeted invoked the Fifth Amendment rather than testify against themselves or incriminate others. Senator McCarthy, with his acute ear for demagoguery, called people who invoked their constitutional rights “Fifth Amendment Communists.” The film business, not constrained by the niceties of constitutionality, agreed to blacklist anyone who admitted to being or who was accused of being a Communist. Scholars estimate that hundreds of people went to jail and tens of thousands lost their jobs.

As Hay astutely figured out, once the forces of inquisition—rural, anti-intellectual, insular—were unleashed, homosexuals would be the obvious targets. After all, Jews had been persecuted and killed only recently; blacks could look for support to the visibly activist NAACP, which had just recently obtained upgrades for the disproportionately black blue-discharge victims while homosexuals got nothing.

The scene for focusing on homosexuals was actually set a little earlier, when, as luck would have it, the perfect symbol of everything the McCarthyites hated—New Deal President Franklin Roosevelt’s wealthy Boston Brahmin undersecretary of state Sumner Welles—got caught with a Pullman porter one drunken night in 1940. By 1943, even FDR’s loyalty (as a boy, Welles had carried Eleanor Roosevelt’s bridal train) could not save Welles from being fired. Thanks to the fuss over Welles, once the witch-hunting for Communists got going after the Communists conquered China and the Soviet Union exploded its atom bomb, the problem of homosexuals in the State Department was teed up. Lost China and too interested in china: the gossip about the gay State Department became so dire by 1950 that a DC newspaper carried a cartoon portraying an anxiously heterosexual former diplomat boasting, “I was fired for disloyalty!”

The nature of homosexuality, being behavior and feelings, made it uniquely vulnerable to persecution and much harder to defend than the congenital, morally neutral characteristics like race and gender. The inquisitors did not usually argue that homosexuals were more likely than others to be Communists. They did argue that gays might be blackmailed into treason, although a decade and a half of inquiry never produced a single instance of such a thing. Mostly, though, the prosecution and discharge of homosexuals from the government was justified on the grounds that their behaviors were immoral and their feelings were crazy or both. Someone who was already immoral (or crazy) might do other immoral (or crazy) things like betray their country, the gay hunters argued.

Despite much speculation, no one really knows why longtime bachelor Senator McCarthy was significantly uninterested in the problem of homosexuals in the United States government, but the task was left to North Carolina Democratic senator Clyde Hoey and Nebraska’s Republican senator Kenneth Wherry. In 1950 Wherry, using his position as head of the Senate Committee overseeing the District of Columbia, brought DC vice cop Roy Blick to testify about how many homosexuals must be working for the federal government. Considering how many homosexuals his division had arrested, and what that said about how many homosexuals there were in DC altogether, divided by the percentage of DC residents employed by the federal government, Blick concluded that there must be 3,750 homosexuals working for the feds as of 1950. The exact number had an oddly convincing quality despite Blick’s admission that he had mostly made it up. Senator Hoey’s investigations produced the “finding” that homosexuals threatened national security. A scant seven years later, a Navy Department report concluded that the Hoey report was, well, hooey, but after 1950 the homosexual security threat was a legislative fact. In April 1953, President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed Executive Order 10450 barring “sexual perverts” from federal employment.

And the consequences were scalding. Departments that did keep records indicate that a hundred employees a year resigned or were fired for sexual perversion, rising to four hundred a year between 1953 and 1955. By 1960, the State Department reported firing one thousand homosexuals. Historian David Johnson estimates that the numbers from State imply at least five thousand firings in the government as a whole. Government contractors took their cue from their biggest customers. Congress, which at that time legislated for the District of Columbia, passed a tough new sexual psychopath law and leaned on the DC police to enforce it in order to smoke out individuals who were also federal employees. Jeb Alexander’s old flame Dash lost his job at State when he refused to sign a loyalty oath, and Jeb spent the McCarthy years “terrified that the hideous spotlight will land on me.” “The only thing I regret,” Peter Szluk, head of security for the State Department until 1962, told historian Griffin Fariello about his job firing gays, “was within minutes and sometimes maybe a week, they would commit suicide. One guy he barely left my office and … boom—right on the corner of Twenty-first and Virginia.”

That the lawyer who helped incorporate the Mattachine Society in 1953 was a “Fifth Amendment Communist” came as a surprise to Marilyn “Boopsie” Rieger of one of the LA discussion groups. As the cell-like structure of the guilds reflected, the Mattachine founders had gone to some lengths to keep everyone’s identity a secret. The groups didn’t know who was behind their gratifying new liberation machine; even the first “order” delegates from the groups to the guilds knew only their fellow guild members. Once she found out that the system was concealing people who might be Communists, Rieger attacked the whole system. “To continue working for the cause,” Rieger told her group, “she needed faith in the people setting the policies.”

Had the founders been more experienced, they would never have called a meeting. But, idealists that they were, Hay and the rest of the founders acknowledged that the explosive growth of the Mattachine Society after the Jennings trial required a new structure with more openness and accountability, as Rieger and others demanded. At the founders’ request, two delegates from each guild in California came to the First Universalist Church of Los Angeles. Once everyone got over the amazing sight of some five hundred organized gays and lesbians in one room, the two factions at the 1953 Mattachine convention laid down the terms of argument for the gay revolution from that day forward.

Homosexuals, the founders told the delegates, are different. Because they have been excluded from conventional society for so long, they have a different culture and different interests. Most tellingly, Hay reminded the assembled representatives, they could not protect their marginalized group by distancing themselves from other persecuted people, like the Communists that Coates was attacking. The people coming for the Communists, Hay said, would also come for them. Homosexuals had an interest in a society governed by due process of law. The conservative members might be anti-Communist, but when the interests of homosexuals and the members’ other interests come into conflict, it is the homosexual interest that must prevail, not the others.

Wrong, said Rieger and her allies, Kenneth Burns, a conservative corporate type, and Hal Call, an insurgent from San Francisco. Homosexuals are not like Communists, they argued. Homosexuals are just like mainstream heterosexuals except for what they do in bed. The insurgents thought that people should be judged not by the specifics of their sexual choices, but by the content of their character. And the opportunity to be treated just as ordinary individuals would never come as long as they kept doing uppity things like asking the cops to stop following them around the toilet. Instead, according to Burns, their greatest contribution “will consist of aiding established and recognized scientists, clinics, research organizations and institutions … studying sex variation problems.” The new homosexual order of sameness would hold no place for what would later be called the transgendered minority either. As it happens, at about the same time, the doctors like Harry Benjamin who were doing sexual-reassignment surgery were developing a regime of complete changeover followed by disappearance into the heterosexual society, accompanied, presumably, by a new sexual interest in people of the (now) opposite sex.

The sameness approach had enormous appeal. Unlike Hay’s Communist Party, the Mattachines had not come together because they shared common beliefs in the inevitability of the dictatorship of the proletariat or some such thing; their commonality was their same-sex attraction and practices. Put to a vote, they would probably all have wished to stop being entrapped and discharged from their jobs, but how to get there—into the melting pot or beyond the melting pot—was the difference that could not be bridged. The Mattachine convention also introduced the practice that was to bedevil gay organizations for decades: governance by charisma. Hay’s communist idealism had saddled the society with the curse of unanimity, rather than the bourgeois conventions of majority rule and rules of order. Absent such orderly procedures, whoever spoke last always seemed to carry the day.

At the end of that day, it was Senator McCarthy who won (again). One of the insurgents proposed that all members sign a loyalty oath of noncommunist affiliation. Although they probably still controlled the majority of the delegates to the convention, Hay and Rowland and the other past or present party members knew that they and their membership could never withstand the scrutiny of the McCarthyite investigations, which were at that point at their height. The founders met and agreed they had to step down. Six months later, corporate sales manager Burns opened Mattachine’s November constitutional convention as the new head of the organization. From then on, there would be no political questionnaires. Hay and the others left. Hull and Jennings and other activists like Don Slater took refuge in the independent ONE magazine to fight another day. Hay was as close to suicide as he ever came in his long, productive life.

The new Mattachines provided something rare in social history—a controlled experiment. They tried advancing the homosexual cause without hewing to the principles of a successful social movement. Instead of putting forth their own ethics, the new Mattachines promised to conform as much as possible to the ethics of the existing society. Instead of characterizing themselves as a culture, the Mattachine members were to accept the characterizations of others, especially the members of the psychiatric establishment and other medical professionals. Instead of advocating their own interests, the Mattachines would work only through persons who commanded the “highest possible public respect.” The last thing they wanted, one such individual advised them, was to make special pleas for themselves as a “minority.” Stripped of its charismatic and driven founders, after 1953, the Mattachine Society almost ground to a halt. Discussion groups deteriorated into group therapy, membership plummeted, and the society referred calls from jail to a list of outside lawyers.

As the Mattachine Society hit bottom, in 1955, a tiny group of San Francisco lesbians started a social club, the Daughters of Bilitis. Phyllis Lyon and Del Martin had met and become lovers a couple of years before. Moving to San Francisco, they shyly ventured to the only place they knew to meet other lesbians, a lesbian bar, hoping to make friends they didn’t have to pretend with. When they stumbled across the grand total of five other lesbians who wanted to start a group, they offered their little house high on the hills above the city for meetings. Soon they were borrowing the mimeo machine from the local Mattachine chapter (“we didn’t think men were good for much,” Phyllis recalls, “but we could borrow their mimeo machine”) to put out a little newsletter, The Ladder. When the Daughters wanted to start dancing together at their meetings, they asked Phyllis and Del to put up curtains across the picture windows looking out at the bay. Someone might see them, the women feared.

Howl (Against the Dying of the Light)

The conventional faction of the Mattachine Society couldn’t have chosen a worse time to cave in. In 1954, one year after the Mattachine members drove out their visionary leaders, Senator Joseph McCarthy made the fatal error of turning his crusade against a real armed force—the United States Army. The army, ably represented by a Boston lawyer, Joseph Welch, took the senator down in a legendary confrontation fueled by what then passed for viral media, television. After repeatedly trying to deflect McCarthy from attacking a young lawyer in his firm as a former member of the left-wing National Lawyers Guild, Welch finally blew up: “You’ve done enough. Have you no sense of decency, sir, at long last? Have you left no sense of decency?”

Carried by three major television networks, Welch’s defiance of McCarthy began to wake the nation from its fevered dream. A few months later, the Senate censured McCarthy and he died in disgrace shortly thereafter. Within thirty days of McCarthy’s downfall, African Americans, asserting their status as a discrete and politically isolated minority, won a unanimous victory from the Supreme Court of the United States, ordering the end to segregated public schools. In 1956, Congress took up the first civil rights legislation since Reconstruction.

Ignorant of his lack of stature, a humble government clerk-typist formed a little Mattachine chapter in DC, called the Council for Repeal of Unjust Laws. The handful of men in the DC Mattachine Society had noticed that the civil rights bill under consideration by Congress did not include homosexuals and that some of the most avid advocates of racial civil rights were among the biggest homophobes. They wrote to the national Mattachine Society about their plans to agitate to repeal unjust laws; the national office wrote back telling them to stop. The Mattachine charter, national said, only allows its chapters to engage in research and education. At about the same time, Philadelphian Barbara Gittings found a copy of ONE magazine and took her next vacation in California. By the time she left Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon’s living room, she was hooked. “You want to do something?” they asked. Start a New York chapter.

Just as the San Francisco headquarters of the Mattachine Society was telling their Washington members not to bother with unjust laws, a mile away, at San Francisco’s City Lights bookstore, Beat poet Allen Ginsberg was reciting his poem “Howl.” The Beat movement was at first a collection of young poets and writers who had migrated to the cheap galleries and bookstores and raffish reputation of San Francisco. There they gathered around an advocate of modernist poetry, Kenneth Rexroth, and inexplicably began to change American culture. Within a few years, the ragtag group of impoverished bohemian poets were immortalized in the pages of the New York Times Magazine. It says a lot about the political impotence of the fifties that poets would make a revolution. But they did.

Consistent with San Francisco’s long history of sexual libertinism, gay and straight, the Beat movement was both gay and straight. The Black Cat Bar, whose straight owner, Sol Stoumen, had fought a twenty-year battle with the government liquor police, was, according to Ginsberg, the “best gay bar in America.” The atmosphere of freedom drew rebels and poets to San Francisco for decades, including, in 1972, a young gay man named Cleve Jones. The emergence of San Francisco as a gay mecca is due, in no small part, to the Beats and their bookstore, City Lights.

A paean to “the best minds of my generation … who let themselves be fucked in the ass by saintly motorcyclists, and screamed with joy,” “Howl” aroused the police to arrest and the state to prosecute the bookstore owner, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, for obscenity. As luck would have it, three months later, the United States Supreme Court decided Roth v. United States. Books were only obscene under the US Constitution, the court suggested, if the “dominant theme taken as a whole appeals to the prurient interest” to the “average person, applying contemporary community standards” and is “lacking in the slightest redeeming social importance.” The court found that Roth’s product met even this difficult standard and still upheld the defendants’ jail sentences, but the opinion, which set new standards for obscenity, had immediate repercussions in San Francisco. Invoking Roth, a local judge acquitted Ferlinghetti, calling the poem a work of “redeeming social importance.”

The “Howl” case hinted that under Roth the presence of homosexual material didn’t automatically remove a publication from the protections of the Constitution. Just in the nick of time. The last remnants of the radical Mattachine Society, which had stayed at ONE magazine after the conservative takeover, were turning out some pretty confrontational stuff. In August 1953, the US Post Office held up mailing of ONE for three weeks before it passed up the opportunity for a showdown. ONE responded to the government’s act of tolerance with a cover essay in its next issue titled “ONE Is Not Grateful.”

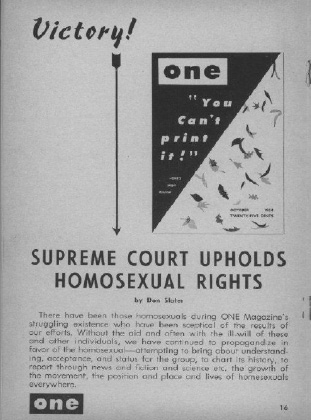

Despite the bravado, the editors of ONE asked their young heterosexual lawyer, Eric Julber, for a list of rules to avoid censorship. In the October 1954 issue, they published Julber’s rules under the cover “You Can’t Print It.” In a classic act of camp, the “You Can’t Print It” issue contained several items that violated the prohibitions on what to print: a story, “Sappho Remembered,” that ended with the heroine choosing her lesbian lover over a conventional life and a poem, “Lord Samuel and Lord Montagu,” that mocked the English prosecution of prominent homosexuals such as Sir John Gielgud (“some peers are seers / but some are queers”). When the post office took the bait and seized the October issue, ONE sued the postmaster in Los Angeles, Otto K. Oleson.

ONE lost both at the trial court and the court of appeals. In its opinion, the court of appeals acknowledged that it faced a rising tide of protection for sexually explicit material:

Much is now presented to the public, through eye and ear, which would have been offensive a generation ago, but does not today merit a second thought as to propriety. None the less, so long as statutes make use of such words as obscene, lewd, lascivious, filthy and indecent, we are compelled to define such expressions in the light of today’s moral dictionary, even though the definition is at best a shifting one.

Taking direct aim at the self-conscious moral claims of the ungrateful ONE magazine and its homosexual constituency, the court said, “An article may be vulgar, offensive and indecent even though not regarded as such by a particular group of individuals constituting a small segment of the population because their own social or moral standards are far below those of the general community. Social standards are fixed by and for the great majority and not by or for a hardened or weakened minority.”

Turning to “Sappho Remembered,” the court ruled that anything that ends happily for homosexuals must be obscene: “The climax is reached when the young girl gives up her chance for a normal married life to live with the lesbian. This article is nothing more than cheap pornography calculated to promote lesbianism.”

So there it was—a clear invitation to the United States Supreme Court to rule that anything positive about homosexuality was automatically obscene and not entitled to the protection of the Constitution. In 1958, the Supreme Court turned the invitation down: “The petition for writ of certiorari is granted and the judgment of the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit is reversed. Roth v. United States, 354 U.S. 476.” It is impossible to express the meaning of ONE v. Oleson better than ONE did on the issue that followed: “By winning this decision ONE Magazine has made not only history but law as well and has changed the future for all U.S. homosexuals,” Slater exulted. “Never before have homosexuals claimed their right as citizens.”

Cover of ONE magazine proclaiming the first-ever homosexual Supreme Court victory, 1958 (Courtesy of the ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives at the University of Southern California, ONE Incorporated records, Collection 2011.001)

The Homosexual Citizen

The editorialists at ONE couldn’t have known how quickly after their Victory an actual homosexual would claim his rights as a citizen. Frank Kameny was, he says, innocently taking a piss at the San Francisco bus station bathroom when the guy next to him made a pass. Maybe so. Of course, Kameny, a little over thirty, tall and thin with dark eyebrows over blue eyes, wasn’t someone you’d throw out of bed either. The two cops watching the men’s room through a ventilation grille that summer day in 1956 arrested him. The next morning they offered him the chance to plead guilty and leave town when his astronomers’ convention ended. He wouldn’t even leave a record, the probation officer at trial told him, if he petitioned the court to dismiss the charge after his probation was over. Sure enough, after Kameny completed his six months’ probation, the court entered a plea of not guilty and dismissed the complaint. When Kameny applied for a job as an astronomer with the federal government later that year, he admitted having been arrested, but said it had been dismissed.

Within a year, his bosses at the Army Map Service in Washington noticed the disorderly conduct arrest on his job application and called him in to ask if he had “engaged actively or passively in any oral act of coition, anal intercourse or mutual masturbation with another person of the same sex.” Although he was clear about his sexual orientation by the time they asked, Kameny refused to answer. “This was a personal matter with no relation to my job performance.” The commander of the map service fired him for not describing his offense adequately on his application form, and the Civil Service Commission followed with a ruling that he was immoral and thus unsuitable for federal employment.

By the time the army fired Kameny in 1957, other sections of the federal government, like the State Department, had logged several years of discharging a homosexual a week, without provoking a murmur from the ruined ex-bureaucrats, unless you count the occasional sound of gunshots to the temple. They had no idea what they were starting when they picked on Kameny. Brilliant, geeky, with a penchant for pure reason, and an uncanny memory for numbers, Kameny was one of those New York Jews who goes to Queens College at fifteen and winds up with a PhD from Harvard. No corporate sales manager or executive secretary, like the conformist leaders of the Mattachine Society, Kameny has always judged the world simply according to the extent to which it conforms to what he thinks. “If the world and I differ on something,” he says, “I’ll give it a second look and I’ll give them a second chance to make their case, if I still differ, then I am right and they are wrong and that is that.” No one could have invented a better character to represent the movement at its turning point than this man.

As a boy, Kameny had spent years going to the Hayden Planetarium in New York every month, each time it changed the exhibits. Before his arrest in a San Francisco toilet, he had quit school to fight the Nazis, seeing combat repeatedly in the American push across the Rhine. He came back from the war to get a PhD in astrophysics. During his postdoctoral year at the observatory in Tucson, Arizona, he met seventeen-year-old Keith, “who actively seduced the very willing” young astronomer on his twenty-ninth birthday. During his “golden summer” with his first love, Kameny used to drive up to Keith’s family cabin in the cool heights of Mount Lemmon every morning as dawn broke and ended his nights looking at the stars. (The two never completely lost touch. In May 2004, Keith, then married under the Dutch same-sex marriage law, called Kameny to note the fiftieth anniversary of their meeting.) Kameny settled in happily at the map service, even entertaining a dream of being an astronaut until someone noticed his admission of a disorderly conduct arrest on his job application.

The conservative paladins of the Mattachine Society may have shunned any comparison to Negroes or any other minority, but Kameny thought it through and decided to make the United States government recognize that homosexuals were no more deserving of persecution and discrimination than “those against Negroes, Jews, Catholics or other minority groups.” He immediately began to appeal his discharge, filing every conceivable motion with the administrative agencies within the civil service. When the civil service rejected him, he took it to federal court.

Although he had managed to convince the local office of the national American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of the injustice of his treatment, by the time his case reached the Supreme Court in 1961, his ACLU lawyer told him he could not win. The lawyer quit, leaving him to represent himself in the final, predictable defeat. Nationally, the ACLU had a policy treating homosexuality as conduct raising legitimate security concerns, a policy that would not change for almost a decade: homosexuals were subversive, and so not eligible for an equal share in the liberal state. In the hand-made brief to the Supreme Court that finally ended his unsuccessful legal quest for reinstatement, Kameny wrote, “It is in the public interest that many questions and issues relating to homosexuality be dealt with … realistically, civilizedly, and directly.”

Kameny doesn’t remember how he found out the court had rejected his petition, ending his life as an astronomer forever. Oh well, he says, there was nothing he could do to retrieve his professional life so he just moved ahead and took control of the gay movement. Many of the people interviewed for this book have said that at one time or another they contemplated suicide rather than face the reduced lives their homosexuality condemned them to. Not Kameny: “Oh no no no no no no no no, never. I never thought about what I had to give up. I am right and they are wrong and if they won’t change I will have to make them.”

With no other legal avenues available to him, he started gathering his friends to found a political organization to address the issues the court would not take up. After all, he had to do something to make the other guys change.

Earlier, when he realized he had been caught in the career-ending, life-altering federal discharge machine, he got in touch with the tiny gay movement of the time, and the Mattachine Society had given him fifty dollars. Kameny certainly wasn’t a Communist, and he didn’t know much about Harry Hay or the coup of 1953 at the time. But he knew fifty dollars wasn’t going to do it. At his instigation, on November 15, 1961, a new Mattachine Society with no ties to the national group—the Mattachine Society of Washington—opened its doors.

“Nobody was doing anything,” Kameny recalls. So the Mattachine Society of Washington commenced doing everything. He made a lifelong alliance and friendship with New York Daughters of Bilitis’s Barbara Gittings, who kept finding herself on the radical edge over at the Daughters. Eventually the handful of little societies formed a confederation, the Eastern Conference of Homophile Organizations. Where the other homophile organizations looked to the clergy and to psychiatrists for help, Kameny realized that “if we were going to be granted the equality we were seeking it was not going to be given to a bunch of loonies.” Anyway, as a scientist, he had long resented being analyzed by people he knew to be unqualified to speak to the subject of their supposed expertise.

Instead, Kameny helped found a DC chapter of the ACLU. The two organizations were so closely related that the Mattachine Society of Washington delayed its founding meeting a week so its founders could attend the founding of the new civil liberties organization. Stalin’s championship of the Negro minority had inspired Harry Hay, and now the Negroes were making the case for the rights of minorities, what we now call civil rights. Kameny had seen the litigation that had fueled the civil rights movement; knowing he was starting a civil rights movement, he too lined up with the ACLU.

But if litigation wouldn’t do it, he was prepared to try other techniques. He was not alone. The year was 1961. Buses full of Freedom Riders were just coming back from the South. A little band of unhappy students at the University of Michigan thought they should work toward a more democratic society.