Riot. Strike. Riot: The New Era of Uprisings (2016)

PART 1: RIOT

CHAPTER 1

What Is a Riot?

At stake in the definition of riot is not simply the possibility of making useful historical distinctions, but the deciphering of the riot’s political significance and potential. It is also a problem for research. Certainly, riots often feature violence, direct, indirect, or threatened. Problems arise once the two are indexed to each other. If one is, for example, parsing public records and selects violence and related words for search terms, this indexing will have a profound effect on the results. Just so, the presupposition that violence indicates a riot will instantly present challenges for any useful conceptualization of the activity in question.

Consider the confusions that proliferate once one makes the conflation, in this example from the opening of Gilje’s Rioting in America:

Even in the opening years of the nineteenth century, just as workers refined their strike tactics, coercion was needed to enforce unity and to persuade owners of the legitimacy of the laborers’ demands. That coercion frequently took the form of rioting—whether it was tarring and feathering a recalcitrant shoemaker in Baltimore, or brawling with strikebreakers on New York docks. Force was often garnered to meet force, and riots and violence represent the signposts of American labor history from the 1830s to the twentieth century. Before 1865 most violent strikes were limited to cracked heads and were local affairs. After 1865, the rioting became national in scope. In the great railroad strike of 1877 workers fought the military from Baltimore to San Francisco. The dimensions of these labor wars continued to capture national headlines with battles at Homestead in 1892, Pullman in 1894, Ludlow in 1914, and Blair Mountain, West Virginia, in 1921. Add to these major cataclysms countless skirmishes in the cities, towns, and countryside, and we can see that much of the history of American labor is written in blood as riots.1

The riot, we are somewhat surprised to learn, is a signal aspect of labor history. It is an adjunct to the strike, its armed wing. Or perhaps riot is simply a subcategory, the violent strike; these sometimes rise to the status of “labor wars,” eventually arriving at the final, grammatically awkward flourish, determined to place the words “riots” and “blood” in closest possible proximity.

As is often the case with even the most arbitrary concatenations, a truth is nonetheless captured. The echo of “written in letters of blood and fire” is suggestive. Marx’s famous description of primitive accumulation insists on the violence of the expropriations producing the conditions of possibility for capitalism. As the chevaliers of industry replace the chevaliers of the sword, it will henceforth appear that the appropriation of surplus under capital, unlike all previous modes of production, is secured through assent freely given. But this double freedom of labor—from the means of subsistence, and to dispose of one’s capacities at will—is precisely what was secured by that originary violence, which is not dissolved, but rather sublated and preserved within the impersonal domination of the labor relation.

It can be no wonder, then, that violence stalks the scene of labor. This is the kernel of truth in Gilje’s retelling, and the moment in which violence could have been recognized as analytically independent from the constitution of riot. With such a clarifying separation, the ideological force of this exclusive association could come up for inspection. This is precisely what does not happen. It is the character of bourgeois thought to preserve moral rather than practical understanding of social antagonism. So, instead, we encounter the remarkable insistence that violence is always and in every case the sign of riot—even when it involves “brawling with strikebreakers,” an evident absurdity. Citing “some legal precedent,” Gilje will eventually arrive at his completed definition of riot as “any group of twelve or more people attempting to assert their will immediately through the use of force outside the normal bounds of the law.”2 A riot, we cannot help but notice, is the perfect obverse of a jury.

The riot is, in this telling, always and everywhere illegitimate, which might not surprise us but for the initial claim that it has served “to persuade owners of the legitimacy of the laborers’ demands.” From there, the categorical problems only proliferate. The consequence of this particular telling is to reduce the strike in its entirety to that most minimal and ascetic aspect, the inaction to be found in the downing of tools. It is always pacific and always within the law—this despite the long stretches of history during which even the meekest strike or “combination” has been illegal, and against the countless examples of picket line struggles and other forms of violence.

Through such counterfactual constructions, we obtain a gravely narrowed model of strike, both in terms of what actions it might comprise, and its scope historical and geographical. Indeed, the strike contemplated here barely exists at all. Such a definition has as well the contrary effect of broadening and disfiguring our sense of riot beyond any particularity; it is to be found in all times and places as something verging on transhistorical essence. A more persuasive but still limited definition is offered by David Halle and Kevin Rafter:

[The riot] involves at least one group publicly, and with little or no attempt at concealment, illegally assaulting at least one other group or illegally attacking or invading property … in ways that suggest that authorities have lost control … the attacks on another group or on property to reach a certain threshold of intensity.3

This might be usefully contrasted with the assessment of William Sewell, one of the foremost historians of collective action. While drawing on Tilly, Sewell, too, gives violence pride of place within his analytic framework across historical periods, concluding, “Tilly’s essential argument can still be explicated most economically by using his typology of competitive, reactive, and proactive violence.”4 Where Sewell differs from Gilje is that, by displacing the riot/strike terms onto registers of violence rather than overlaying the two frameworks by force, he is able to reckon the shift from one leading orientation to another within a repertoire of actions open to historical transformation. That is to say, he retains the possibility of periodizing as such. This is exactly what Gilje effectively abandons by obscuring fully half of the work of history. Tilly notes,

The repertoire of collective actions evolves in two different ways: the set of means available to people changes as a function of social, economic and political transformations, while each individual means of action adapts to new interests and opportunities for action. Tracing that double evolution of the repertoire is a fundamental task for social history.5

The account of riot as the protean expression of general social violence changing form willy-nilly as circumstances dictate informs the second half of this, while effacing the first—and, with it, any chance of grasping the systematic import of the riot’s return.

The Economic and the Political

The equivocation of riot and violence has been an essential tool in the political reduction of the riot, its cordoning off from politics proper, the measure of which rests implicitly on a model of self-consciousness or its absence. It was this that Thompson set out to pillory, calling it a “spasmodic view” of popular history:

According to this view, the common people can scarcely be taken as historical agents before the French Revolution. Before this period, they intrude occasionally in moments of sudden social disturbance. These irruptions are compulsive, rather than self-conscious or self-activating: they are simple responses to economic stimuli.6

Such conceptualizations are renewed in the positivistic, quantitative science of, for example, the New England Complex Systems Institute. Their 2011 study, focused on low-wage nations, charts a single-bullet correlation wherein the authors “identify a specific food price threshold above which protests become likely.”7 There are more nuanced departures from these underlying suppositions, articulating unbearable rises in commodity prices with broader economic changes, such as IMF restructuring programs and enforced trade relations, that provide the conditions for precarious food regimes. Emphasizing the constructedness of famine and dearth, these accounts nonetheless assume a veritably autonomic mechanism of enchained stimulus and response. The effective definition of riot here is conditional. It is simply what happens once food prices achieve a certain apogee, a version of the approach by “growth historians” dismissed by Thompson for “obliterating the complexities of motive, behavior, and function, which, if they noted it in the work of their Marxist analogues, would make them protest.”8

Such an approach finds its counterpoint somewhat perversely in Alain Badiou. He offers an abstracted, qualitative sense of the political moment. In many regards, his account transcends the limits of his contemporaries, left intellectuals who, confronted with the Tottenham riots of 2011, found little to learn. At best, we were given to understand, the riots achieved a sorry spontaneism, that accusation which is socialist thought’s reanimation of the “spasmodic” trope. It was an odd spectacle to see a once-modern political theory offered as a truism, as if the debate between Lenin and Luxemburg had been settled and its conclusions were good for all time, no real analysis required. In general, the reports were even less generous. The participants were dupes of the society before them, driven by the self-canceling compulsions of the age, avatars of materialistic individualism momentarily unshackled, perhaps eligible to escape from meaningless outbursts if provided a political program. As Slavoj Žižek inquired plaintively from the paper precincts of the London Review of Books, “Who will succeed in directing the rage of the poor?” It was hard not to fear that a philosopher might wish to appoint himself the task.

Badiou, however, is clear that the riots to which he turns his attention are not in search of a vanguard directorate without which they can only affirm the society from which they burst forth. He identifies them as a periodizing fact in the midst of its own realization:

several peoples and situations are telling us in a still indistinct language that this period is over; that there is a rebirth of History. We must then remember the revolutionary Idea, inventing its new form by learning from what is happening.9

The Idea arises from the event of the riot, which it then provides with an organizational force and duration.

In this schema, there is a certain alternation between periods in which “the revolutionary conception of political action has been sufficiently clarified … and on this basis has secured massive, disciplined support,” and “intervallic periods [when] by contrast, the revolutionary idea of the preceding period … is dormant.”10 Lacking an ordering idea (often appearing as the majuscule Idea), these latter periods give rise to the expression of that disorder in the protopolitical mode of riot. Badiou sees an “uncanny resemblance” between our recent past and the French Restoration following the final defeat of the Republican spirit: “from the start of the 1830s it was a major period of riots, which were often momentarily or seemingly victorious … These were precisely the riots, sometimes immediate, sometimes more historical, characteristic of an intervallic period.”11

The purely economistic and the purely political, as might be expected, display each other’s limits in negative. The indexical tale told by the New England Complex Systems Institute can do little but attend to certain quantities as they approach given levels and then await the riot that will inevitably follow. Their method appears to be relatively accurate, after the way of hard data, but it is scarcely explanatory regarding the riot as social phenomenon.

Badiou’s recounting, inversely, is admirably explanatory but inaccurate. That is to say, he provides a recognizable social context for riot as opposed to other forms of action, a periodizing claim, and he is prepared to accept the riot as serious testimony about historical transformation. There are nonetheless vagaries in his historical survey, which derives somewhat arbitrary periodizations of French history from imputed political desires, toward a global trajectory of riot to which such a historical apportioning does not correspond. The oscillating movement he educes for France, with phases lasting decades, has little periodizing force; arguably accurate for his native country, it matches little if at all with the tendencies of history elsewhere. Moreover, any given riot of political significance (a “historical riot,” in his typology) appears as a practically determinationless event, outside of time. The quants give us too much causality; Badiou too little.

These two approaches stand before us like Scylla and Charybdis, the hard shoals of vulgar economism and the whirlpool of political abstraction. How to navigate between them, between the riot as hunger game and the riot as emanation of a diaphanous structure of political feeling? No doubt, each is in some sense informative but not yet sufficient. If we have stressed periodization, it is first because fundamental and lasting changes within the repertoire of collective action suggest that periodization is possible in forms more thoroughgoing than spasm or oscillation, on both infranational and supranational scales. If the riot looks at periodization, the period in turn peers back at the riot through the dialectical keyhole. It is hard, perhaps impossible, to establish what a riot is without periodization; with it, the riot (and strike as well) can be understood as a set of practices in the face of practical circumstances, with or without an imaginary regarding the reflexive self-awareness of participants on which so many accounts rest.

It is on practice that Thompson founds his analysis. His conclusion aggregates a colloquy of other practices, including blockade, seizure, resale, threat and actual violence against traders and transporters. It is from these, in relation to a customary sense of the cost of staying alive, that he deduces the practice of price-setting as the unifying activity. Thompson has been in turn critiqued for the weight he gives to custom and to the assumed right to weaponize custom that is seized by the crowd. However, the more basic case he builds approaches the inarguable: the case for recognizing that the situation of riot is neither simple hunger nor political “emotion” (as riot had once been called), but rather the domination of the marketplace. If it was “the point at which working people most often felt their exposure to exploitation, it was also the point—especially in rural or dispersed manufacturing districts—at which they could most easily become organized,” and was thereby “as much the arena of class war as the factory and mine became in the industrial revolution.”12

Talk of class war cannot help but threaten a certain reductionism itself. It does not seem, at least in the orthodox sense it has acquired, entirely adequate to the protoindustrial world in question, nor to the present, when class belonging provides no less a limit than a logic for political mobilization. Just so, as our introduction notes, “price-setting of goods in the marketplace” describes only a fraction of the contemporary riot. Thompson, and he is not alone, points toward a way out in a moment of attention to the subject of the riot. He pauses in his survey to remark, “Initiators of the riots were, very often, the women,” for the evident reason that “they were also, of course, those most involved in face-to-face marketing, most sensitive to price significancies, most experienced in detecting short-weight or inferior quality.”13

This is only reasonable, that those excluded in advance from the “patriarchy of the wage”14 would encounter most keenly the struggle in the marketplace, once subsistence agriculture is undermined and the basic matter of survival is forced into an expanding sphere of exchange. And this offers us more than a logic of circulation, the sphere of consumption and exchange. It further begets a logic of reproduction as such.

The Dilemma of Reproduction

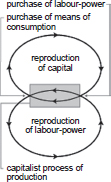

Social reproduction is always two-sided. From the side of the dispossessed of capital, it is both the sale of labor power and the purchase of what is needed to reproduce that labor power. From the side of capital itself, it is the valorization of commodities in production and the realization of that value in exchange. These are the same activities, evidently enough, seen from different positions. The clearest illustration of reproduction’s double character, its contradictory unity, is the so-called double moulinet or, in German, zwickmühle, a word that English translates as “dilemma.”

In the traditional telling of this dilemma, it is a story of labor: of labor power remade and resold for the wage, and of reproductive labor endlessly appropriated toward this process, most commonly as unwaged “women’s work.” What Thompson catches a glimpse of is that this reproductive work happens not just in the home—kitchen, bedroom, nursery—but is also, in the period he surveys, routed through the marketplace. When the marketplace seems to provide the main situation for reproduction, struggles over reproduction will inevitably situate themselves there. At the same time, we cannot help but notice that this situation does not apply to all subjects equally—that those who are last in and first out of the wage, those who have never been included, those who at best achieve secondary access, will be at the forefront of those who find themselves struggling over reproduction in ways beyond the wage. In this parceling of participants, we encounter another way to see the conjuncture of the eras marked as riot and riot prime.

Double moulinet

In the introduction, we settled on a tripartite definition of strike as the form of collective action that struggles to set the price of labor power, is unified by worker identity, and unfolds in the context of production; riot struggles to set prices in the market, is unified by shared dispossession, and unfolds in the context of consumption. Strike and riot are distinguished further as leading tactics within the generic categories of production and circulation struggles. We might now restate and elaborate these tactics as being each a set of practices used by people when their reproduction is threatened. Strike and riot are practical struggles over reproduction within production and circulation respectively. Their strengths are equally their weaknesses. They make structured and improvisational uses of the given terrain, but it is a terrain they have neither made nor chosen. The riot is a circulation struggle because both capital and its dispossessed have been driven to seek reproduction there.

If this seems a somewhat technical language for a sensuously laden experience—a dramatic social antagonism charged with danger and fury and desperation and a certain social pleasure—this is only in answer to the conventional dismissals of the riot already encountered, by way of presenting an argument that should not have needed making in the first place. The riot, comprising practices arrayed against threats to social reproduction, cannot be anything but political. This is not to say that the contradiction of reproduction can be resolved within circulation any more than within production. It is in fact the existence of those two spheres, in their unity and contradiction, that guarantees the existence of and gives form to struggles for reproduction. If the vast expansions of the industrial revolution provide the surpluses for the development of modern military and police apparatuses, they also provide surpluses that can be used to purchase social peace. As these surpluses melt away and increasing portions of the population are rendered surplus to the economy in turn, the state turns more and more to coercion as a management style: the social wage of the Keynesian compromise is withdrawn in favor of police occupation of excluded communities.

Police and riot thus come to presuppose each other. The riot comes to know itself through this imbrication. Walking through Hackney during the riots of 2011, past scenes of distress and excitement, past burning trash bins and the detritus of looting, some observers concluded that “a coherent struggle was being waged here … to insist upon respect from the cops, force recognition of a subject where daily grind sees only an abject.”15 The passage points to riot as a necessary relationship with the current structure of state and capital, waged by the abject—by those excluded from productivity. But it also points to the riot’s dependence on its antagonist. In the moment, the police appear as necessity and limit.

This is the dialectical theme, this dilemma of necessity and limit. The marketplace, the police, circulation. These are not situations where any final overcoming is possible; they are where struggles begin and flourish, desperately.