A Curious History of Vegetables: Aphrodisiacal and Healing Properties, Folk Tales, Garden Tips, and Recipes - Wolf D. Storl (2016)

Common Vegetables

Bell Pepper and Chili Pepper (Capsicum annuum, C. fructescens)

Family: Solanacea: nightshade family

Other Names: green pepper, sweet pepper, cayenne pepper, ornamental pepper

Healing Properties:

TAKEN EXTERNALLY: topical applications warm and relax muscle tissues, reduce pain; ideal for rheumatism and lumbago

TAKEN INTERNALLY: stimulates blood circulation, thins the blood; increases stomach digestive juices and lessens nausea (as such supports alcohol withdrawal); induces sweating; lowers fever; reduces pain; strengthens the immune system

Symbolic Meaning: incarnates the fire power of hot summer: awakens zest for life; generates inner cleansing; protects against evil eye/sadness; stokes creative energy

Planetary affiliation: Mars

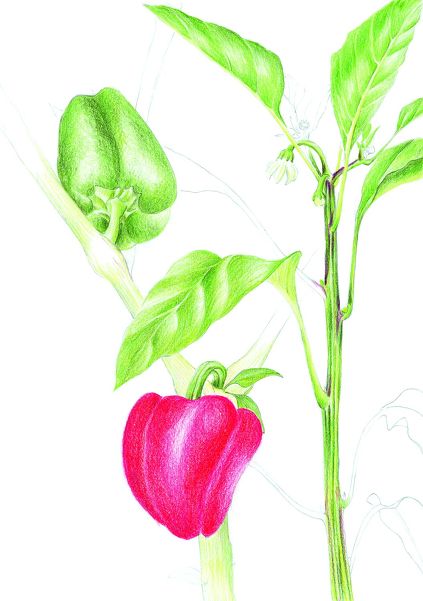

How to describe peppers? Some are colorful—bright yellow to deep red—crispy, fleshy pepper fruits that make a feast for the eyes. Some are the more or less hot and spicy peppers that pep up soups and meats. They are abundantly available in supermarkets and are found in the plots or green houses of enthusiastic gardeners who pamper them into thriving. The many kinds of Capsicum—from those with lip-burning long pods to the fleshy sweet ones and mild—all belong to the same genus as part of the nightshade family. They love the summer heat and need a temperature of at least 66 °F (19 °C) in order to blossom—otherwise there will be no fruit. In the tropics they are perennials, just as tomatoes are, but in northern climates they are annual plants perforce. The “pods,” which are actually berries, contain plenty of vitamins—mainly vitamin C and provitamin A—and the spicy substance capsaicin (from the Greek capto, to bite), which can still be tasted in dilutions of 1:2,000,000.

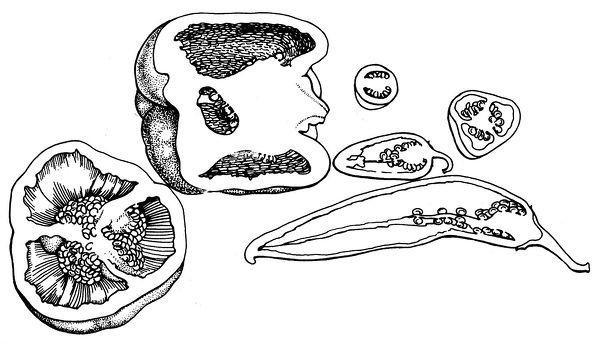

Illustration 14. Bell pepper and chili pepper cut in half

Many people associate the pepper with Hungary—and for good reason. The word “paprika” is Hungarian, though it derives from the Serbo-Croatian word “papar” (pepper). Indeed, paprika is at least as intimately connected to the Hungarian soul as, for example, cucumber with the Polish soul, cabbage with the German soul, or potato with the Irish soul. Peppers—some pale and mild, some bright and hot—are echoed in Hungarian music, which often ranges from soft and melancholy to passionate, even ecstatic. And the character of this plant fits very well with the formerly wild, shamanistic horse-riding people from the western Asian steppes that settled in the Danube River area in between agricultural Slavs and Germanics. The Hungarians believe that peppers protect from the evil eye and wicked vampires. For example, pepper pods are put under the pillows of women in childbirth in order to protect them. But the strongest association derives from the fact that paprika is the Hungarian national seasoning, used in their famous goulash, salami, and gypsy schnitzel. Hungarian gardeners naturally cultivated a whole pallet of various kinds of paprika, and Hungarian scientists have vigorously studied their “soul plant.” In fact, Albert Szent-Györgyi (1893-1986), director of the Institute of Medical Chemistry at the University in Szeged, was the first to prove that paprika contains four to six times the vitamin C found in lemons or oranges.

Despite all of this, pepper did not come to Hungary until shortly before the eighteenth century. Legend tells that a Hungarian water-carrier named Ilona smuggled some of the “Turkish pepper” fruits from Ottoman governor Pasha Mehmed’s flower garden in Buda. The Turks, who also cherish the fiery plant, had gotten it from the Spanish, Sicilians, or Portuguese in the sixteenth or seventeenth centuries—and they, in turn, had learned of pepper from Native Americans.

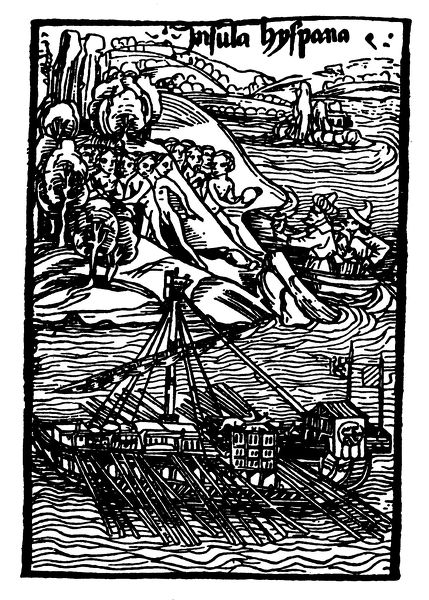

Toward the end of the Middle Ages Europeans were addicted to exotic spices, especially black pepper. But the export trade in spices was controlled by middlemen Arabs, who monopolized the ports of Venice and Genoa and charged shockingly high prices. It was precisely high demand for expensive exotics that prompted Christopher Columbus to sail west in search of India. Of course, Columbus did not reach India, and he did not find black pepper, but he did find red pepper; he and his crew were the first Europeans to do so. This occurred on January 15, 1493, on the island of Haiti. The maritime explorers did not like the hellish hot peppers the Haitian natives called “ají,” but it is said that on the return trip Columbus did eat dried peppers as treatment for heartburn or chest constriction. On the admiral’s second trip, the ship’s doctor, Dr. Chanka, took some seeds—which he prescribed for migraine—back to Spain. And under the hot Spanish sun the plant thrived. In this way, “Spanish pepper” began its long world journey, and soon found its way into African kitchens, where the sharpest and spiciest kinds are cultivated, and into Indian and Indonesian cooking, where it is used in curries and sambals. Interestingly, India, the country of black pepper, is today the biggest producer of red pepper, specifically extremely sharp capsicum.1

Archeological finds indicate that peppers have been cultivated for at least seven thousand years in tropical America. In Mexico alone over seventy kinds are still cultivated—about one-third milder varieties and two-thirds hotter. It’s the spicier strains that give such dishes as chili con carne, tamales, and other Mexican culinary delights their typical flavor. (“Chili” is the Aztec’s Nahuatl word for pepper.) Indeed, the Aztecs peppered all their meat with the fiery seasoning—such as Chihuahua meat (the maize-fed dogs were raised as we raise chickens), turkey, and other game. Some scholars claim that the upper classes also cannibalized the enemies captured in the “flower wars,” who were sacrificed in rituals performed atop the temple-pyramids. With obsidian knives they cut out the victim’s beating heart, offering it to the sun god Huitzilopochtli as food; later the victim’s head was placed in the temple. Some contend the victims’ torsos were served to the elite in a spicy pepper and tomato stew garnished with squash leaves; other scholars consider incidents of Aztec cannibalism to be much more the exception than the rule.

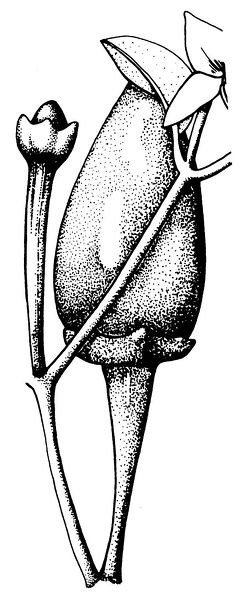

Illustration 15. Chili pepper

Another misappropriated origin tale of the pepper concerns Tabasco sauce, named after a river in Mexico. But the hot sauce was actually the discovery of Edmund McIlhenny (1815-1890), a New Orleans banker who fled the Yankees during the Civil War. After the war he came back to what little remained of his sugar cane plantation and villa. With nothing left to harvest but a crop of Mexican pepper pods, McIlhenny mixed the chili peppers with vinegar and salt and steeped the brew in oak barrels. He later sold perfume jars filled with the devilish-smelling brew to a large distributor, whereafter it became a culinary hit. And the name Tabasco? The entrepreneur simply loved the sound of the name (Panati 1987, 404-405).

Traditional Medical Use

Peppers play a significant role in the cuisines of tropical countries because they have a bacteria-killing quality that keeps foods from spoiling too quickly. The spicy ingredient capsaicin simultaneously discourages intestinal parasites and stimulates digestive juices in the stomach, which helps in the digestion of carbohydrate-rich foods commonly found in developing countries. The hot spices also induce sweating, which vaporizes on the skin and cools the body.

But there is another reason that people love this vegetable, whose biting sharpness nearly burns the mouth and draws tears to the eyes. In 1992 Australian scientists at the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO), reported that our reaction to extreme spice is in reality an impression of pain, which triggers the body’s opiates—essentially feel-good endorphins. Some people in fact become addicted to hot spices (Dayton, 1992). (This knowledge is, however, not really as new as it may seem: the 1741 edition of Württemberger Pharmacopeia cites: “Spanish pepper has a caustic effect and therefore lessens pain in inner organs”).

For thousands of years Native Americans have discovered many medicinal properties of this nightshade plant. Aztecs found peppers to energize the body, strengthen the stomach, and encourage flatulence—as well as to serve as a diuretic, laxative, and sexual stimulant. They made an expectorant tea of the leaves for asthma and breast pain. From the roots they made a tonic for stomach pain and colic. Rashes were treated with hot urine and paprika powder. Incas and other Peruvian Indians drank corn beer (chicha) seasoned with hot peppers for constipation and as a diuretic and aphrodisiac. For the Mayans hot pepper was known as a heal-all used in different preparations for tuberculosis, sore throat, diarrhea, cramps, blood in the stool or in the urine, coughing blood, delayed afterbirth, black widow bites, rheumatism, hemorrhoids, dizziness, skin ailments, and toothache. For earaches the blossom was rubbed between the fingers and wrapped in cotton blossoms and then put into the ear. For bone pain and cramps paprika leaves were cooked and added to a bath. Hot peppers were also rubbed into wounds or onto boils: though the ensuing pain was so strong that the patient often fainted, it was claimed that the bad “magic” that had caused the disease could be killed in this way.

Everywhere Native Americans used chili pepper for fevers—not so much to lessen the fever but to support the fire of life, to energize and to bring the strength of the sun back into the body. During sweat baths cayenne pepper tea supported the effects of the heat. For flu South American aboriginals drink spicy corn beer to increase sweating—which we know today is a sensible cure. The heat, combined with the effect of hot pepper, has a strong stimulating effect on the immune system. This method was the core of the medical reform movement of Samuel Thomson (1769-1843) in the nineteenth century. These patients were given a hot tea with a purgative in it containing cayenne pepper, lobelia, and various herbs for the specific sickness. A portion of the tea was also administered as an enema. After the resulting purge the patient was given a steam bath followed by a cold shower. As these methods often brought about spectacular cures, such approaches are finding their way into modern natural healing as well.

Illustration 16. The Spanish land in Haiti (medieval woodcut)

In Mexico today paprika plants are still used to cleanse (limpia) the body of evil spirits or curses by rubbing the body with pepper fruits. (In age-old country practices European grandmothers added so-called “spell plants” to the baths of children who’d been cursed.) The limpia is prescribed for a number of conditions: when the evil eye has been cast upon someone; when someone is affected by the aires—the cold, sickening wind from the ghosts of the dead, wicked witches, or from wee men who dwell in caves or near springs; or when someone has been “shamed” (as in public mortification, dishonor, or ridicule) or “saddened” (as in depression). As many Mexicans believe all of these states can lead to vomiting, diarrhea, nervousness, or sleeplessness. Hot chili peppers are applied to burn the negative energy.

Illustration 17. A Peruvian woman cooking peppers

Of course, this ancient vegetable is also a magical and ritual plant. For the Guayupe Indians in Venezuela, for example, after a couple had their second child the father would retreat alone, fast, and then wash his entire body with a pepper brew; it was thought that if he did not perform such austerities the child would die. This Indio tribe allowed only virginal girls to sow the pepper seeds; otherwise, they believed, the seeds would not germinate. The Chibcha tribes in Colombia doused hot chili brew into the eyes of adulterers. Orinoco Indians rubbed hot chili salve into their arrow tips. European magicians and witches on the order of Harry Potter make an amulet out of green pepper seeds to strengthen their own energy. And, as mentioned earlier, pepper serves as an aphrodisiac; according to the Magister (Master) Botanicus, a modern school of magical herbalism in Germany, it makes us “hot.”

Modern phytotherapy recommends a capsici tincture be rubbed into the joints for rheumatism. Cayenne tincture is also used to help alcoholics overcome their addiction. New research shows that pepper also helps lower cholesterol levels, as the spicy seasoning stimulates circulation and dissolves coagulated blood in the arteries. The hot power of chili peppers is also said to combat winter depression (seasonal affective disorder). Some even claim that, used as a flower essence, cayenne stimulates fire; its resulting energy helps to remove blockages so that the soul can develop (McIntyre 2012: 252).

Garden Tips

CULTIVATION: Pepper seeds should be started in a well-lighted greenhouse or a protected room for about ten weeks before they are transferred outside to a very sunny spot after there is no more danger of frost and the air and soil temperature remains above 50 °F (10 °C). Mulch around the plants to keep the soil moist and the weeds down. (LB)

SOIL: All pepper varieties like rich compost in the soil; magnesium and phosphorus are especially important.

Recipe

Bell Peppers Stuffed with Hummus ✵ 4 SERVINGS

BELL PEPPERS: ¾ cup (175 grams) chickpeas, cooked ✵ 4 tablespoons almond butter ✵ 2 tablespoon sesame oil ✵ 1 teaspoon coriander powder ✵ 1 tablespoon lovage leaves, finely chopped ✵ 2 tablespoons parsley leaves, chopped ✵ 8 tablespoons sunflower seeds, soaked in water ✵ paprika ✵ herbal salt ✵ pepper ✵ 4 bell peppers (preferably green), tops cut off as lids, cored, seeds removed ✵ CHILI GARLIC SAUCE: 1 cup (225 milliliters) olive oil ✵ 2 to 3 garlic cloves ✵ 2 to 3 chili peppers, cored and cut into strips ✵ a few drops of lemon juice

SAUCE: Put all the ingredients in a small sauce pan and simmer, covered, on lowest heat for about 4 hours. Let cool. Drizzle some sauce on the stuffed peppers. (See also TIP below.)

BELL PEPPERS: Note that the peppers can be eaten raw or baked. If you choose to bake them, preheat the oven to 350 °F (175 °C). In a medium bowl, mash the cooked chickpeas; mix in the almond butter and sesame oil. Add the coriander, lovage, parsley, and sunflower seeds. Season to taste with paprika, herbal salt, and pepper. Fill the prepared bell peppers with this mixture. Bake at 350 °F (175 °C) for 40 minutes or until peppers are tender; alternatively, they can be eaten at room temperature. Serve drizzled with the garlic sauce.

TIP: The sauce is best prepared in a larger quantity, as such produces a more intense flavor. The quantities for 1 quart CHILI GARLIC SAUCE is as follows: 1 quart (945 milliliters) olive oil ✵ 20 garlic cloves ✵ 20 chili peppers, cored and cut into strips ✵ 1 teaspoon lemon juice ✵ Put all the ingredients in a large pan and simmer, covered, on lowest heat for about 4 hours. Once the sauce has cooled, pour it into sterilized jars; store the sealed jars in a cool place. The sauce will keep well for a few months.