A Curious History of Vegetables: Aphrodisiacal and Healing Properties, Folk Tales, Garden Tips, and Recipes - Wolf D. Storl (2016)

Forgotten, Rare, and Less-Known Vegetables

Shungiku or Garland Chrysanthemum (Glebionis coronaria, Chrysanthemum coronarium)

Family: Compositae:, daisy or aster family

Other Names: chop suey green, crown daisy, edible chrysanthemum, Japanese green, garland-chrysanthemum

Healing Properties: BLOSSOMS: reduces high blood pressure, soothes eyes, reduces headaches, heals infections; LEAVES: clears skin ailments and acne, heals abscesses

Symbolic Meaning: queen of flowers, longevity, autumn, reclusiveness, beauty in difficult circumstances, commemoration of the dead (East Asia); nobility, Christ, sun god, oracle flower, St. John (Europe)

Planetary Affiliation: sun, Venus

This garland chrysanthemum that we grow as an ornamental flower is cherished in eastern Asia as an aromatic leaf vegetable. It is part of the Japanese national dish, sukiyaki, which is made with tofu, strips of meat, onions, bamboo shoots, and other vegetables cooked in soy sauce, rice wine (sake), and sugar. The buds of the chrysanthemum, also known as shungiku, are pickled in vinegar. In China the young leaves are added to chop suey (the Cantonese shap sui = mixed together) along with bean sprouts, bamboo sprouts, onions, mushrooms, fish or meat, soy sauce, and water chestnuts.1

This plant germinates well and grows quickly, especially when supplied with enough water, sun, and good garden soil. As it grows quite tall, it should be placed where it won’t shade other crops. The young sprouts can be eaten raw in salads, soups, and mixed vegetables; they taste especially good with tomato salad. If one does not tear out the shallow roots when harvesting the sprouts, they will continue growing new shoots. Shungiku begins to blossom in the late fall, when the days get shorter, and will continue to flower profusely until the air gets too frosty. (It was a joyful experience for me the first time they bloomed in my garden, as the many bright yellow blossoms transformed my vegetable garden into a flower garden. I also enjoyed the flowers as garnishing for salads.) Shungiku can take quite cold weather. It can be sown fairly early in the year and then in intervals of two weeks. It is easy to keep some seeds for sowing out the next year.

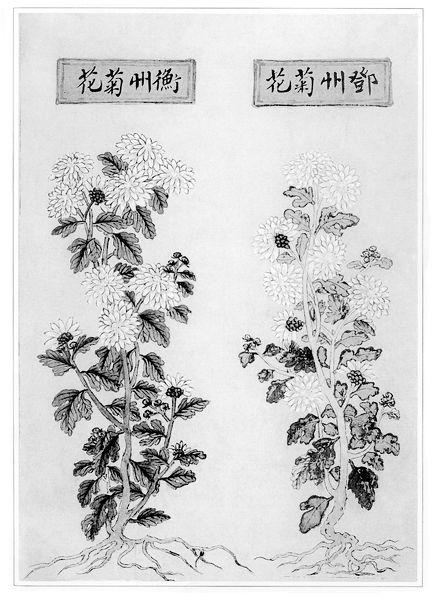

Illustration 95. Chrysanthemums (from the Ben cao gang mu, an encyclopedia of premodern Chinese pharmaceutical knowledge edited by Li Shizhen, sixteenth century)

This golden flower belongs to the composite family. In Europe, the most well-known member of the chrysanthemum genus is the oxeye daisy. Children like to put the flowers in their hair, and it’s a favorite for the playful “He loves me, he loves me not” pastime. This was the flower poor Gretchen plucked, considering this very question, in Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s 1808 tragic play Faust. For the Celts and Germanics of long ago, oxeye was a symbol for the sun; it was the “day’s eye” (daisy), that is, Baldur’s eye (the pre-Christian sun god); later it came to symbolize Christ’s eye. The young shoots of the oxeye are also edible, as modern-day wild food expert François Couplan informs us (Couplan 1997, 40).

The corn marigold, or corn daisy (C. segetum), which is also cultivated as a garden vegetable in Southeast Asia, is nearly identical to shungiku, especially its golden yellow blossoms. In the nineteenth century corn marigold was called a “bad flower” because it came to Europe from the Ukraine as an aggressive invasive plant. It spread like wildfire in the grain fields, and was fought viciously in Germany and Scandinavia. In Germany, names like “Groschenblume,” Hellerblume,” and “Batzenkraut”—all of which refer to money—remind of the fees that farmers had to pay if government inspectors found even one sample of this alien plant in their fields. Sadly, our modern agricultural practices and herbicides have brought this once-invasive plant to near extinction. Nowadays the pretty flower has become so rare it’s been put under nature conservation.

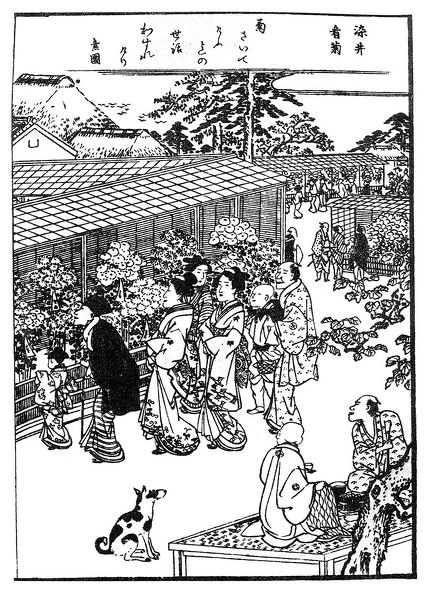

Illustration 96. Chrysanthemum exhibit in old Japan

The Mediterranean costmary, or balsam herb (Chrysanthemum balsamita), also belongs to this family. First dedicated to the goddess, it was later attributed to the Holy Mother; churchgoers often used one of the leaves as a bookmark for their Bible. The fresh leaves once seasoned soup, lamb roast, lentils, and herb liquors.

Various chrysanthemums, such as the Dalmatian pyrethrum, have active ingredients that are harmful to insects, fish, and amphibians—but not to warm-blooded mammals. For example, pyrethrum is the active ingredient in mosquito coils used to keep mosquitos out of tents. Since the pyrethrum in the Dalmatian chrysanthemum is an effective insecticide, it is sometimes used by organic gardeners against pest infestation.

Practically all the showy ornamental chrysanthemums or mums originated in East Asia. There, this “queen of flowers” has the same symbolic value as the lotus in Southern Asia or the rose or lily in the West. The plant decorates temples and shrines, and is a motif for artists painting porcelain, embroidering silk, or carving and sculpting in wood and metal. In Japan the sixteen-petaled chrysanthemum is the emperor’s flower: it is found on the coat of arms, embroidered on royal kimonos, and engraved on the emperor’s sword. In China and Japan the chrysanthemum festival is elaborately celebrated on the ninth day of the ninth month. The twin of the spring festival of cherry and plum blossoms, the fall festival symbolizes the end of the year, the turning from a life of toil back to a simpler life, the blessed time of rest found in winter. Chinese poet Tao Yuanming (365-427) wrote:

Autumn chrysanthemum in magnificent bloom,

I picked them in the morning dew

To take their purity into my soul as

I sit here alone with my glass of wine.

The golden flower symbolizes beauty maintained in a world full of haste and meanness. It reminds us of friends and ancestors who are gone and whispers gently of the love that transcends death. The flower is also a symbol of longevity (Beuchert 1995, 49). The flower is so noble that the Chinese empress did not find it below her dignity to cultivate the flowers for the palace herself. A court lady wrote: “Every day all of the court ladies and eunuchs accompanied the empress to the western shore of the lake. According to her instructions we cut small branches from the young plants and put them into flowerpots. When there was heavy rain her majesty ordered the eunuchs to shelter the chrysanthemums with delicate straw mats” (Tergit 1963, 130).

At the fall chrysanthemum festival, the Japanese drink a cup of sake with a golden blossom in it. It is a sacred rite that confirms their loyalty and allegiance to the emperor. The custom goes back to when twelfth-century Emperor Go-Toba gave his loyal knight Kusunoki Masashige such a drink as a sign of appreciation. Since those days of old, the Japanese and Chinese have cultivated thousands of wonderful kinds of chrysanthemums, some of which found their way to Europe via a merchant from Marseille during the French Revolution. Chrysanthemums have been cultivated in the royal gardens of Versailles since 1838.

Illustration 97. Chrysanthemum in a basket (Japanese sketch)

The native European chrysanthemum, the pretty oxeye daisy, was once used as balsam for wounds, and as a diuretic and sudorific tea. Nicholas Culpeper (1616-1654), who put the plant under the rule of Venus, advised using the plant for “swollen and hot testicles.” Naturally, in Eastern Asian medicine both the wild and the cultivated plant are also used medicinally. Indeed, the flower was mentioned in Shennong Bencaojing, believed to be the oldest herbal book, written by the third-century BC emperor Shennong, venerated as the father of medicine; it underlines the significance of the chrysanthemum that its use is traced to this mythical figure. The carefully dried flowers (in Chinese ju hua) are cooling, antibacterial, and detoxifying. In Chinese folk healing the flower is used for headaches, dizziness, and sleeplessness;2 combined with the blossoms of Japanese honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica) it is given for high blood pressure, angina pectoris, and arteriosclerosis (Foster and Chongxi 1992, 194).

In eastern Asia the chrysanthemum has played a role in household medicine for a very long time. It is used for headaches, bad breath, bitter taste in the mouth, and other diseases that come from “cool wind.” Cooked, warm blossoms are placed on tired, red eyes—such as after one has spent hours at the computer. Fresh, crushed leaves are applied for skin ailments like acne, boils, and eczema; in the winter dried leaves are scalded with hot water for the same purpose. The Chinese sleep on pillows stuffed with dried, aromatic chrysanthemum blossoms. Wine with chrysanthemum blossoms is considered strengthening. In Southern California the plant Chrysanthemum coronarium has become what some consider an invasive plant—possibly escaped the garden of Asian immigrants. But is this a problem? With its bright yellow flowers, the bloom can only beautify the countryside.

Recipe

Green Asparagus with Fried Shungiku ✵ 2 TO 4 SERVINGS

1 pound (455 grams) asparagus, cut in 1-inch pieces ✵ 4 tablespoons olive oil ✵ ½ cup (115 milliliters) white wine ✵ 4 tablespoons (50 grams) cream (18% fat) ✵ sea salt ✵ ¾ cup (175 grams) shungiku ✵ good-quality, neutral-tasting (such as sunflower) oil for deep frying ✵ tamari or soy sauce

Add the olive oil to a medium lidded pan. Sauté the asparagus, covered, for 5 minutes or until tender. Add the white wine and cream. Season with salt to taste. Simmer for 10 minutes. Deep-fry the shungiku. Serve the asparagus with the frittered shungiku alongside the tamari or soy sauce.