A Curious History of Vegetables: Aphrodisiacal and Healing Properties, Folk Tales, Garden Tips, and Recipes - Wolf D. Storl (2016)

Common Vegetables

Pumpkin and Squash (Cucurbita pepo, C. maxima, C. moschata)

Family: Cucurbitaceae: gourd family

Other Names: gourd, Jack-o’-lantern, pepo, vine

Healing Properties:

Flesh: eases kidney ailments, obesity, and stomach ailments

Seeds: eases prostate hyperplasia and urinary infections, expels worms

Symbolic Meaning: world egg (Native Americans, Africans), primeval union of yin-yang, luck-bringer, long life (China), shortness and elusiveness of life (Christian); honoring the dead; end of summer; Halloween and St. Martin’s Day

Planetary Affiliation: moon and Jupiter

On December 3, 1492, on the island of Cuba, Christopher Columbus became the first European to lay his eyes on a pumpkin field. He knew at once that the opulent pumpkin plant, with its big, rough leaves and tendrils, yellow-gold blossoms, and rotund orange fruits is an “Indian” variety of the Cucurbita, or Curbita, the melons (Cucumis) and gourds (Lagenaria) of the Old World.

In northern Europe, aside from cucumbers and poisonous bryony, the latter of which was used in occult rituals, not much attention was paid to this plant family—perhaps because these plants need a lot of warmth and are very sensitive to frost. Watermelons had been known in Mediterranean countries since ancient times, and were served—like ice cream today—as common refreshments. And gourds, with their hard, dry shells, were used by the Romans to make containers, drinking vessels, and rattles. But otherwise the cucurbitas were considered to be commonplace. This American pumpkin, however, was of a completely different caliber.

For North and South American natives the pumpkin was a nutritional mainstay, and one of the oldest plants cultivated. Like corn and beans, it was regarded as an incarnated goddess descended from the heavens. Pumpkin seeds found in caves in Oaxaca, Mexico, and other places are dated to be some 10,000 years old. These were wild plants, though—the flesh scant and bitter. They were gathered for their seeds, which contained valuable protein and oils. Over the course of several thousand years, Native American gardeners bred and cultivated hundreds of squash varieties of different sizes, shapes, and colors—acorn squash, banana squash, chayote, crookneck, flying saucer (also called “scallop squash” and “pattypan squash”), golden nugget (also called “Oriental pumpkin”), zucchini, and many, many others—all of which have delicate, easily digestible flesh.

Illustration 63. “Santa Maria,” flagship of Christopher Columbus, the first European to see a pumpkin

In the Americas of today gardeners still produce a striking variety of this plant family, all referred to as squash. Because the white settlers had no word for this unusual vegetable, they took over the Narragansett Algonquian word “askutasquash” (“green thing eaten raw”), which they simplified to squash. (In Britain, where the term “squash” refers to either a pressed citrus fruit juice or a game similar to tennis, the vegetable is called “vegetable marrow.”) Americans distinguish between winter and summer squash, the former kinds (C. maxima, C. moschata) have a round stem and are eaten when fully ripe; the latter (C. pepo) have a square stem and are usually eaten before they are ripe. Most of the various members of this plant family need a very long period of sun to ripen; therefore in northern climates only a few kinds thrive. Among these various summer squash, the extremely productive zucchini (“courgette” in France and Britain) is an all-time favorite in personal vegetable gardens. Blossoming continually, each plant repeatedly produces long, green, cucumber-like fruits—so many that a single family cannot consume them all. One solution to this “problem” is to fry some of the blossoms in batter—a first class delicacy!—before they get a chance to ripen.

Illustration 64. Extraterrestrial “pumpkin head”

The giant pumpkin (C. maxima) is probably the largest vegetable of the entire plant kingdom. In the year 1900 at the Paris World’s Fair (Expostition Universelle) a 400-pound pumpkin with a diameter of three feet broke the established record; in 2014 a Swiss accountant grew a pumpkin weighing more than a ton (2,323 pounds). With possible genetic manipulation, the future might bring us even bigger pumpkin monsters.

As it was for the Native Americans, the pumpkin also has cult status in modern America: as both Halloween jack-o’-lanterns and pumpkin pie at Thanksgiving, the harvest time festival. This celebration and feast serves to remind us of the Pilgrim Fathers who were saved from starvation by the local Amerindian tribe, the Wampanoag, in the winter of 1620. Sadly, we tend to forget that the Wampanoag were shortly afterward expelled and nearly extinguished by these very settlers.

By the end of the sixteenth century pumpkins were also grown in the gardens and fields of the Old World. Nonetheless, it took Europeans a long time to warm up to eating them as a vegetable. Even today in France pumpkin is mainly used as cattle fodder. The huge berry—botanically speaking it’s a berry!—instead inspired fantasy visions, both then and now. Charles Perrault (1628- 1703) incorporated it into his version of “Cinderella” by having the fairy godmother turn a pumpkin into Cinderella’s carriage. And “galactic boat people,” extraterrestrials that have supposedly crashed in the Mojave Desert, are generally called “pumpkin heads” (which is, of course, also a term for a nitwit).

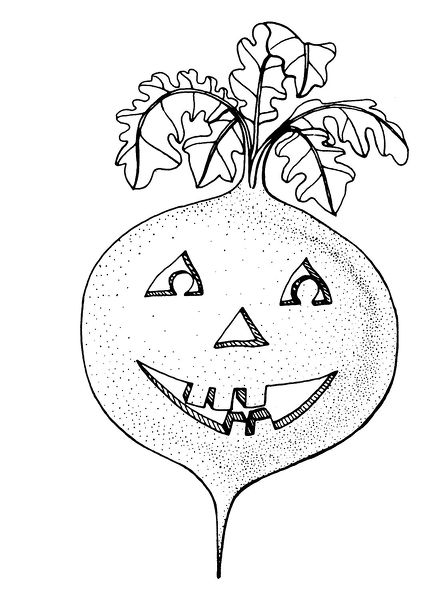

Records suggest a variant of Halloween has been celebrated since the Megalithic age, the era when Stonehenge was built. Then it was an end-of-the-year-festival, when winter was about to set in and the spirits of the dead temporarily left the “other world” to roam about begging for food. The Celts called these holy days “Samhain,” and celebrated them at full moon in November; in later eras they were known as “All Hallows’ Eve.” In order to receive blessings and protection from the departed, and to avoid being spooked or haunted, people would set out food offerings and lights on their doorsteps. The lights consisted of lanterns made by hollowing out big turnip roots, carving faces into them, and placing candles inside. The lit-up turnip roots represented the full moon, as it was thought the sprits of the dead traveled on moonbeams. (Since Classical antiquity, European Christians believed the souls of the dead ascended first to the lunar sphere, the first rung on the “ladder of heaven.”) When the descendants of these people came to America, they replaced the turnip with a pumpkin, and the festival became more secular and commercial, in time morphing into the trick-or-treat holiday we know today.

Illustration 65. Before pumpkins came to Europe, lanterns were carved out of turnips for “All Hallow’s Eve (Halloween)

Anthropologists consider the important Mexican holiday Día de Muertos (The Day of the Dead) to have originated some three thousand years ago. To this day candied pumpkin meat is offered to the departed as food on this holiday, now celebrated on November 1. This is yet another example of how, as a lunar plant, the pumpkin has long had a strong association with the dead. For another, in Slovakia it was the custom to boil garlic and squash stems in water with which to wash down the chairs and table where a dead person had been lying in state; the room was then sprinkled with this water. These precautions, it was believed, ensured the ghost would not come back to haunt the room.

As pumpkin and various other squash vegetables came to be known throughout the Old World, each region developed its own relationship to the quaint plants. For the Chinese, the pumpkin became a symbol for the primeval oneness of yin-yang; for the Africans it is the world egg, with the seeds of all beings within it. Because of the pumpkin’s plentiful seeds, to the Turks it symbolizes the female ovary, protecting from the “evil eye.” In Cairo pumpkins are hung to protect from the evil eye.

In rural South Africa pumpkin also became part of the folklore and healing lore. The Zulus and other Southern African peoples cook the yellow blossoms into a kind of relish that is eaten with corn mush, and roasted seeds are a popular snack. The herbal healers of the Zulus, the inyanga, cook pumpkin leaves and put them on the chest as hot compresses for pneumonia. They also recommend a tea made of the roots for rheumatic pains and ground seeds to get rid of tape worms.

Illustration 66. Woman and child carrying a pumpkin on their heads (illustration by K. Paessler, Gärtner Pötschkes Großes Gartenbuch. 1945)

The Spanish, who strictly discern between categories of “hot” and “cold” in their traditional healing, prepare the seeds (semena frigida majora) as a remedy for cooling intense, lustful passion and for lessening “hot” seminal fluid. In 1643, Nicholas Culpeper confirmed the “cooling” nature of the plant by placing it under the rule of the moon.

In southern and western France pumpkins are cultivated only as animal fodder; the French cannot imagine finding them tasty. Eastern Europeans, however, befriended pumpkins readily, approaching the plant in a typical Slavic way, pickling its flesh as they pickle its cousin, the cucumber. Hot pumpkin soup and even pumpkin porridge are also popular in these regions. The American favorite, pumpkin pie, on the other hand is considered an exotic dish.

The country folk in Europe also transferred onto the pumpkin the notions of sympathetic magic applied to other big vegetables. Pumpkin seeds, they believe, should be sown on Whitsuntide (Pentecost) Sunday when the church bells ring—so “they will grow to be as big as church bells.” (You may recall a similar belief having to do with cabbage.) For the same reason the seeds should be carried in a big bucket or basket. In Breslau, a woman with big buttocks would sit on the seeds so the pumpkins would grow as big as her bottom; for the same reason one should also tell a big lie while sowing the seed in the ground. In Lausanne, Switzerland, peasants brought the seeds to church to be blessed on Annunciation Day (March 25), the day when the archangel Gabriel announced to the Virgin Mary, she was with child; in the same way that Mary’s belly would grow big and round, so should grow the pumpkins. Other days serve as well: in some regions sowing on May 25, the day of St. Urban, “brings a big turban,” whereas the Polish plant on the day of St. Stanislaus (May 8).

If one sows before sunrise on April 30, St. Walpurgis Day—a festival diametrically opposed to the fall festival of Samhain (Halloween)—the seeds will thrive as fast as witches fly. (We earlier noted the same belief associated with cucumbers.) In Brittany pumpkin seeds are sown on Good Friday so they will “resurrect” in big style.

The Healing Power of Pumpkins

Native Americans well knew the healing benefits of pumpkins. The Mayans used the juice in salves to treat burns. For round worms and tapeworms, the Aztecs made a medicine out of pumpkin seeds, onions, and wormseed (Chenopodium ambrosioides); for bladder and kidney diseases they made a medicine out of the pulp. The Catawba chewed the seeds to cure kidney problems; the Cherokee and Menominee used them as a diuretic and to cleanse the urine for bedwetting, dropsy, burning sensations while urinating, and cramps in the urinary organs.

Folk medicine concerning the pumpkin is quite similar in Europe, where it was traditionally believed the plant derived some of its healing properties from the abundant life energy it radiates. As a bland food, pumpkin flesh is recommended for stomach troubles and kidney/bladder ailments. Fresh pumpkin pulp is applied to furuncles, abscesses, varicose veins, and cankerous sores. Pumpkin seed oil is used to heal cracked skin and wounds, especially burns.

By at least the nineteenth century Europeans discovered something the Aztecs had known centuries earlier: pumpkin seeds get rid of worms. Eating just about ten ounces paralyzes the worms; after thirty minutes they can be excreted with the help of a half tablespoon of castor oil. (The famous Bavarian herbalist and healer Sebastian Kneipp [1821-1897] recommended wormwood tea [Artemisia absinthium] be mixed with the ground seeds.) Modern medical research has shown that the seeds help with benign swollen prostate gland; they contain delta-7 sterols, which resemble the male sex hormone, and dihydrotestosterone—as well as vitamin E and selenium, which have both anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects. And cancer researchers in South Africa are currently studying pumpkin seeds for their peponin, which is thought to block the production of HIV-1 enzymes.

As we see, given its many health benefits—and no known side effects—there are plenty of reasons to include tasty pumpkins in one’s diet.

Garden Tips

CULTIVATION: Before sowing, soak the seeds in milk until they are swollen. After there is no more danger of frost, plant the seeds into raised mounds. You can spur growth by adding liquid compost in the middle of the growing period. Pumpkins thrive very well—and will not get aphids—if grown with nasturtiums and angel’s trumpet. (LB)

SOIL: The pumpkin is a frost-sensitive heavy feeder; it grows best in sandy loam that has been well supplied with rotted manure. A midseason application of compost tea will spur growth. Any kind of quash plants also thrive well when planted into an old compost pile.

Recipes

Pumpkin Salad with Blueberry Sauce ✵ 2 SERVINGS

3 tablespoons mayonnaise ✵ 1 tablespoon olive oil ✵ 1 teaspoon honey ✵ 4 tablespoons fresh blueberries ✵ 1 tablespoon apple vinegar ✵ a bit of freshly ground ginger ✵ herbal salt ✵ white pepper ✵ 1 cup (225 grams) pumpkin, grated ✵ 4 to 6 leaves of endive lettuce

In a medium bowl, mix the mayonnaise, olive oil, honey, vinegar, and blueberries. Season with ginger, herbal salt, and pepper to taste. Add pumpkin, stirring until it’s fully covered in the sauce. Set the endive leaves on a serving dish. Spoon the pumpkin mix onto each leaf and serve.

Pumpkin with Yellow Boletus ✵ 4 SERVINGS

½ cup (115 grams) onions, finely chopped ✵ 1 cup (225 grams) fresh yellow boletus, chopped ✵ 2 bay leaves ✵ 4 sage leaves ✵ 2 tablespoons olive oil or lemon olive oil ✵ 1 cup (225 milliliters) white wine ✵ 1 cup (225 milliliters) vegetable broth ✵ 1 cup (225 milliliters) cream (18% fat) ✵ ½ cup hominy ✵ herbal salt ✵ 2 pounds (905 grams) pumpkin, cubed

In a large pot, sauté the onions and boletus with the bay leaves and sage leaves in the olive oil for about 5 minutes until nicely aromatic. Add the white wine and mix well. Add the vegetable broth and cream and bring to a boil. Add the hominy to slightly bind the mix. Add herbal salt to taste. Simmer, uncovered, for about 20 minutes. Stir in the pumpkin. Simmer, covered, for about 5 minutes.

TIP: Fine butter noodles go well with this soup.