A Curious History of Vegetables: Aphrodisiacal and Healing Properties, Folk Tales, Garden Tips, and Recipes - Wolf D. Storl (2016)

Common Vegetables

Potato (Solanum tuberosum)

Family: Solanaceae: nightshade family

Other Names: Murphy (Irish potato), spud, tater, tuber

Healing Properties: builds up base levels (ideal for the stomach), reduces acidity

TAKEN EXTERNALLY: as a poultice eases joint inflammation, rheumatism, and swollen lymph nodes

TAKEN INTERNALLY: the juice eases heartburn and stomach ulcers

Symbolic Meaning: stupidity, egoism, lack of inspiration, materialism

Planetary Affiliation: moon

After rice, the potato is the second-most-cultivated nutritional plant worldwide—darling of the agricultural industry and private vegetable gardens alike. Potatoes will grow for anyone, even those who do not otherwise have a green thumb. Some children enjoy harvesting them almost as much as searching for Easter eggs. And when it comes to the potato patch, even the most hard-boiled rationalist will at some point dabble in magical thinking: perhaps planting the spuds right after the full moon, or consulting the Farmer’s Almanac for which day the moon will be in an earth sign (Taurus, Virgo, Sagittarius). In Switzerland and other alpine countries, many gardeners note whether the moon is ascending or descending, that is, whether it’s on its way to the highest zodiac sign (Gemini) or heading back down to the lowest sign (Sagittarius). Why? When Luna comes down from the higher zodiacal signs to the lower ones, it is believed she brings life energy down into earth, which is, of course, ideal for the tuber. Then there are other guidelines for when to plant, these concerning the “sidereal moon,” that is, the quality of the sign in which the moon finds itself at the time. For example, old garden rules claim a moon in Virgo is unfavorable because then the shrub will blossom continually, later producing measly, thin tubers; or, if planted when the moon is in Sagittarius, the potatoes will be small and hard; in Aquarius and Pisces they will be watery; in Cancer they will be wormy and scabby. Other signs are favorable, though: if one plants when the moon is in Gemini and Libra, the harvest will be double; when in Leo and Taurus, the potatoes will be big. Furthermore, gardeners consider how close the moon is to the earth: when it is closest (perigee) vs. when it is farthest (apogee). It’s considered best to put the spuds in their beds at the time of moon’s perigee. And then there is also the “synodic moon” to be considered: when it waxes and wanes. As you can see, potato planting can be a complicated business. But there is also an old saying claiming “the dumbest farmer has the biggest potatoes.” There is some truth to this, for such a farmer relies on his gut instinct and intuition, which is often more reliable than abstract intellectual rules when it comes to working with living organisms.

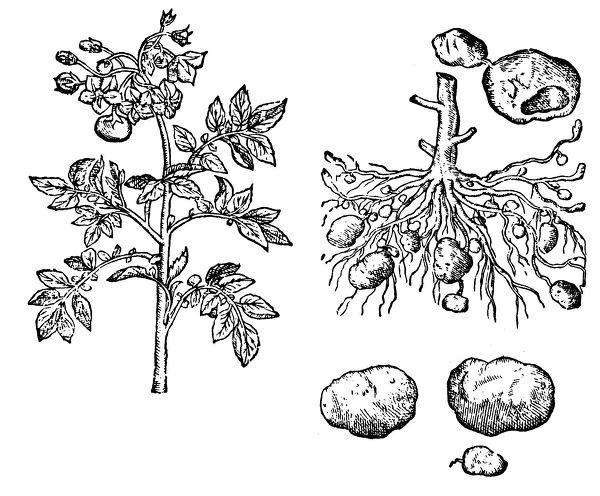

Illustration 59. One of the earliest drawings of the potato (Carolus Clusius, Rariorum Plantarum Historia, 1601)

Nowadays, one can hardly imagine life without the nourishing, starchy tuber. From scalloped potatoes to potato salads, from chips to French fries, there are more potato dishes in the Americas than can be mentioned in one breath. Most regions have their own kinds of potatoes and their own favorite dishes; in Europe, these are as varied as are the different dialects. From dumplings in Saxony, lefsa (soft flatbread) in Norway, and rösti (like hash browns) in Switzerland, potatoes are used in both salty and sweet dishes. A simple potato soup was known to be the favorite food of German emperor Wilhelm II (1859-1940).

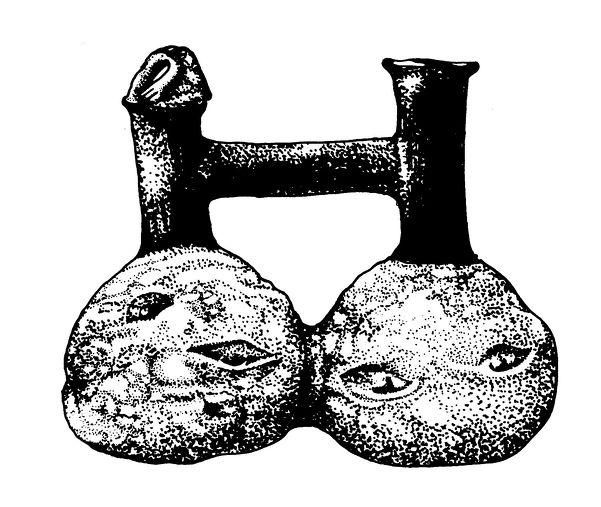

Illustration 60. Potato-shaped vessel of the Peruvian Chimú culture

Fries and chips, which are as much a part of international modern life as are hamburgers and cola, have had interesting beginnings. When French fries (pomme frites) were first made in France in the eighteenth century, they were considered for a long time to be a refined dish fit only for aristocracy. (Thomas Jefferson brought the recipe back from France and served thick-cut fries at Monticello.) More than a century later, this treat led to the accidental invention of the potato chip. A guest in a fancy resort in Saratoga Springs, New York, had ordered the French potato delicacy; being fastidious, he sent the fries back to the back to the kitchen, claiming they were too thick. The hotel’s cook, a mixed-race African American/Native American named George Crum (1822- 1914), made a new batch with thinner strips, but the guest was still not satisfied. Finally Crum decided to fry them so thin they couldn’t be “skewered with a fork.” Rather than being upset, the guest was delighted. Soon these “Saratoga Chips” became the specialty of the house (Panati 1998, 388).

But, despite their long-beloved status, potato dishes were not always so popular. In Europe, when the Spanish first brought the tubers from South America toward the end of the sixteenth century, this nightshade plant was viewed quite skeptically because it was common knowledge that nightshades, such as belladonna or angel’s trumpet, can be very poisonous. At this stage the plant was assumed to have aphrodisiacal and possibly healing properties. Ultimately, it was mainly curious pharmacists or pastors interested in botany who first planted this “apple of the earth” (French pommes de terre) or “American truffle” (the German word for potato, “kartoffel,” comes from the Italian tartufolo = truffle). Indeed, the first potato planted in Germany was in an apothecary garden in Breslau in 1587. But the European royalty was also interested in the exotic plant, and passed it on from court to court, letting their cooks experiment in their kitchens. Of course, one must be careful when experimenting. Sir Walter Raleigh (~1554-1618), who received the plant from an aristocrat, got solanum poisoning from eating the berries instead of the tubers. Queen Elizabeth I (1533-1603) didn’t fare any better when she had potato leaves prepared and served as a sort of spinach; she had received the plant as a gift from the New World from Sir Francis Drake (~1540- 1596), pirate in the service of her Majesty.

Except for the tubers, the nightshade plant is indeed poisonous. Though the potato does not contain tropane alkaloids (atropine or scopolamine) found in belladonna or henbane, the green portions of the plant do contain solanine, which is nearly as poisonous as strychnine. Even small amounts cause stomach pain, cramps, and diarrhea. The solanine in the potato plant functions to both disrupt the skin-shedding metamorphosis of hungry insects and protect its tubers from rot.

Not surprisingly, at first country folk didn’t want anything to do with this exotic tuber. Because of the “signature” of the tubers, the peasants feared eating them might give them leprosy, tumors, or scrofula (lymphadenitis). In some regions the plant was even officially forbidden, as in Besancon in 1630, where the city council declared: “The potato contains poisons that can cause leprosy.” Puritans and the Russian Orthodox did not eat them because they were not mentioned in the Bible; being therefore not the “Word of God,” they must be of the devil. Even today anthroposophists are careful with potatoes, recommending sick people avoid this bloated, proliferous tuber, claiming it dampens the spirit and encourages uninspired materialistic thought.

Only hardship and famine taught people to value the potato. This first occurred in the seventeenth century in British-controlled Ireland. The periodic uprisings by rebellious Irish were suppressed by the British tactic of burning or trampling the fields, an approach that, though effective in destroying grain fields, left potatoes unharmed; potatoes thus helped stave off famine. Then, during colonization the English overlords confiscated the best soils to grow grain and raise beef cattle, which were intended for export. Before long practically all that was left for the Irish to eat were potatoes and skimmed milk.

In Germany, Scandinavia, and Poland it was abject poverty that led to the widespread eating of potatoes. The first potato fields in central Europe were planted in 1680 in impoverished Vogtland, where it was proverbially said:

Potatoes for breakfast,

at midday in the soup,

for supper in their skins,

potatoes ’til I drop!

The rulers of the Age of Enlightenment during the eighteenth century soon recognized the potential of the potato. The economist Adam Smith (1723-1790), the prophet of modern capitalism, recommended mass cultivation of potatoes as a cheap source of food for the working classes. He believed the tubers, which have more nutritional value and produce more bulk per acre than do wheat and other cereal grains, would be more economical.1 More peasants could be relieved of tilling the soil—so he calculated—and put to work in the mills and factories.

In France, pharmacist Antoine-Augustin Parmentier (1737-1813) pointed out to His Majesty Louis XVI that pommes de terre would be good food for the masses; unfortunately, the people weren’t willing to oblige. During the famines of 1780s the clever, upper-class tactician ordered potatoes to be planted in parks and empty lots in and around Paris, the fields patrolled by day by armed guards. In the evening, however, the guards left their posts. Thinking they were outfoxing the pharmacist, during the night the rabble plundered the fields stealing potatoes—just as they were intended to do. Soon Parisians took a fancy to these exotic “earth apples.” The rulers in Prussia and in Russia were less subtle: they simply ordered by decree that all subjects plant potatoes—while simultaneously highly taxing flour. As a result, the consumption of cereals between 1690 and 1790 was halved. In turn, the people came to appreciate potatoes, but not just as food—since it’s also enjoyed distilled as high-proof potato spirits, potato whiskey, or schnapps.

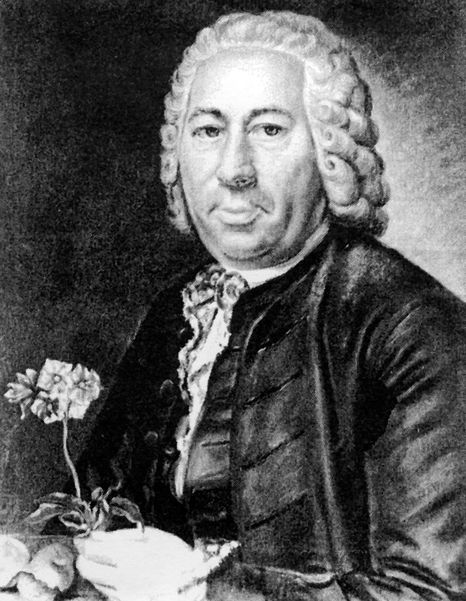

Illustration 61. Antoine-August Parmentier made potatoes popular in France in 1780 (Brendan Lehane, The Power of Plants, 1977)

Prehistoric hunters and gatherers in Monte Verde, Chile, foraged for wild potatoes as long as 10,000 years ago. Later, on the foggy, moist slopes of the Andes where it is too cold for corn, the ancestors of the Incas cultivated potatoes—papas—by creating level terraces that they irrigated. In time they developed some three thousand varieties: white, yellow, red, purple, and brown; big and small, sweet and bitter. (The bitter ones were used only as fodder for lamas and alpacas.) The Incas felt that the potato connected them to the great Earth Mother and to their ancestors. The tuber was also connected to the jaguar spirit, which at times had to be appeased with bloody rituals. They also prayed to Axomama, the potato mother or goddess. In a ritual similar to how European peasants paid tribute to the last sheaf of grain they cut, the Indios honored Axomama in a “ceremony to renew the potato.” First they spread out the harvested potatoes on the ground to let them freeze for three nights; then, after stomping them with their feet until all of the water squeezed out, they dried them in the sun. To this day these freeze-dried potatoes—chuños—are the main staple of the Quechua and Aymara people.

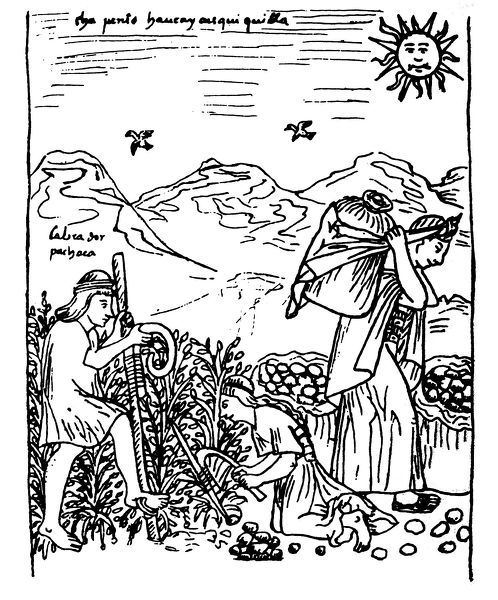

Illustration 62. Incas harvesting potatoes (Spanish drawing, sixteenth century)

The potato deva, a truly mighty being, has changed the destiny of humanity. The Spanish fed their Indian slaves working in the silver mines of Potosí with chuños stolen from the Incas’ larders. With the immense wealth obtained from this mined silver, the Spanish lords financed both their world power ambitions and the Counter-Reformation. But, despite such ill-begotten treasure, the geopolitical center of power migrated—thanks to the potato—from southern to northern Europe. The potato preferred the cool and moist Atlantic climate to that of the hot and dry Mediterranean. Plus, due to its high vitamin C content, the potato became an ideal winter food, putting an end to pernicious scurvy. Soon, potatoes could feed entire armies of soldiers and, a little later, factory workers; potato alcohol also helped the populace to bear the brutality of early industrialization. In this way the productive tuber greatly facilitated the Industrial Revolution in northern Europe.

Potatoes supposedly arrived in the North American colonies in 1621 when the governor of Bermuda, Nathaniel Butler, sent two large cedar chests containing “Spanish tubers” and other vegetables to Governor Francis Wyatt of Virginia at Jamestown. Nearly two hundred years later, Thomas Jefferson, always interested in horticultural novelties, grew them on his estate. But during their early American history potatoes were grown only sporadically in vegetable gardens; they didn’t become a major staple until the influx of the Irish and central and eastern Europeans in the middle of the nineteenth century.

The potato literally revolutionized nutrition in Europe: after its ascendancy, oatmeal, millet, and root vegetables like parsnips, skirret, and rampion vanished from dining tables. The potato tuber, which was thereafter eaten at nearly every mealtime and is easily digested, contains lots of vitamins, proteins, and amino acids (lysine, leucine, valine, etc.), as well as starch and even trace elements (aluminum, nickel, zinc, and iodine, among others). The introduction of the potato enabled Europeans to live longer, healthier lives and reproduce more.

Unfortunately, overreliance on one crop is a dangerous gamble, as was keenly felt in 1845, the fateful year the potato blight (Phytophthora infestans) suddenly appeared in Ireland, rotting and blackening the harvested potatoes. The fungus was especially devastating because all the potatoes were basically a single variety; as they had an extremely narrow genetic basis, they could offer little resistance to the invasive fungus. By the time this blight had lasted three consecutive years, the Irish population had been reduced by half: one-fourth of the Irish starved to death, and one-fourth—some two million people—emigrated, mainly to North America. The beleaguered newcomers, however, were not particularly welcome, being as they were both Catholic and inclined toward alcohol, neither of which suited the Puritan ethos. In addition, the narrow nourishment of potatoes and skimmed milk over several generations had left the Irish rather small in stature. All in all, the resident Caucasian Americans were afraid the Irish “dwarves” would genetically ruin their race. Of course, thanks to the better nutrition to be found in the States the children of the Irish immigrants soon grew as big and strong as their compatriots.

The potato blight raged in other parts of Europe as well, inciting many millions of poor peasants, especially from Scandinavia, the Netherlands, and the German-speaking countries, to make the hard decision to emigrate to the New World. As a result, most of today’s Caucasian Americans are the descendants of potato blight refugees.

Potatoes As Healers

It’s to be expected that healers in Europe appropriated for their own purposes the tuber that had conquered the dining table. At first, seventeenth-century doctors, who didn’t yet distinguish between potatoes and sweet potatoes,2believed that the longish tuber could improve a man’s potency. Indeed, for Shakespeare potato fingers were a symbol of lust:

How the devil Luxury, with his fat rump and

potato-finger, tickles these together! Fry, lechery, fry!

—Troilus and Cressida, Act 5, Scene 2

Henry Hudson (~1565-1611), British commentator on Shakespeare’s works, wrote: “It is said that potato fingers have lust and prurience because it is believed that the potato strengthens the body and creates lust.” This misconception, however, didn’t last long.

In traditional folk medicine it is believed that to carry a potato around in one’s pocket helps against rheumatism. Poultices of mashed potatoes or fresh potato juice are used for gout, rheumatism, and lumbago. Raw, grated potatoes mixed with oil are used for burns, sunburn, and cracked skin. Hot potato poultices are used for infections, bronchitis, swelling, including of the lymph gland, lumbago, and other pain. Raw juice is drunk for stomach ulcers.

Potatoes are said to make people plump and sluggish—the infamous “couch potato.” In truth, potatoes on their own are ideal for keeping a slim figure; it is only the oils used in preparing them that makes them fattening. In increasing quantities of high-pH bases in the digestive system, potatoes help to prevent stomach acidity, constipation, and liver damage. New research suggests they may be anticarcinogenic because they contain protease-inhibiting agents that neutralize viruses and carcinogens as well as Chlorogenic acid, which guards against cell deterioration. In addition they have an antioxidant effect.

But even today there are still critics of the humble potato. Anthroposophists assert: “Creative thinking has diminished in Europe since the time that eating potatoes became popular.” They claim that potatoes make people dumb and egocentric, and that they are partially responsible for the present spiritual state of modern humanity. “The potato,” said Rudolf Steiner (1861-1925), “is digested in the head.” One of Steiner’s followers proclaims that potato consumption does not support inner awareness, that in the long term it can even harm the midbrain and the development and functioning of the brainstem” (Walter 1971, 102). Rudolf Hauschka, another anthroposophist, fears that even the children of excessive-potato-eating parents will have a hard time mastering their cerebral functions. Impressive tuber indeed!

Garden Tips

CULTIVATION AND SOIL: Though potatoes are basically undemanding, it is best they always have a fresh, new place in the garden each year. They should never be planted in the same bed in the following year, or following tomatoes, either; since both are nightshades, they can share diseases. The day before planting, cut the seed potatoes so that there is at least one eye to each cutting with plenty of flesh around the eye; let them dry overnight. Till the soil well the next day, making rows about two feet apart. Well-aged compost can be incorporated at this time. Hoe very shallow trenches and lay the potatoes in, eyes up. (LB)

Recipes

Olive-Potato Ravioli with Browned Butter ✵ 2 SERVINGS

DOUGH: 1 cup (225 grams) whole wheat flour ✵ 2 eggs, plus 2 egg yolks, whisked ✵ 3 tablespoons olive oil ✵ 2 tablespoons vegetable broth ✵ FILLING: 4 ounces onions, finely chopped ✵ some fresh thyme leaves ✵ 2 tablespoons olive oil ✵ 2 ounces black, pitted olives, chopped ✵ 1 cup (225 grams) mashed potatoes ✵ herbal salt ✵ pepper ✵ ground nutmeg ✵ 1 egg yolk, whisked with ½ teaspoon water ✵ 2 ounces butter

DOUGH: Knead the ingredients into a dough. Transfer to a covered container and refrigerate for 4 hours.

FILLING: Sauté the onions and thyme in the olive oil until browned. Add the olives and mashed potatoes. Season with salt, pepper, and nutmeg to taste. Set aside.

RAVIOLIS: Preheat the oven to 350 °F (175 °C). Roll out the chilled dough into a 3-inch log. Slice into rounds about ½ inch thick. Prepare a baking sheet with grease or with parchment paper. Taking 1 dough slice at a time, dab about 2 teaspoons of the filling in the middle of the dough slice. Brush the rim with egg yolk whisked with a few drops of water. Fold the dough in half to create half-moons; pinch the edges together to seal. Place the ravioli on the baking sheet and brush with egg yolk. Repeat with the remaining dough. Bake the ravioli at 350 °F (175 °C) for 10 minutes, or until golden brown. Transfer the baked ravioli to a serving dish.

BROWNED BUTTER: In a small pan, gently heat the butter until slightly browned, about 5 minutes; be sure not to burn it. When ready to serve, drizzle the butter over the ravioli.

Halved Baked Potatoes ✵ 4 SERVINGS

4 unpeeled potatoes, cut in half lengthwise ✵ 2 tablespoons olive oil ✵ salt

Preheat the oven to 350 °F (175 °C). Prepare a baking sheet with parchment paper. Rub each potato half with olive oil. Sprinkle cut sides with salt. Place each half, sliced side down, on the baking sheet. Bake at 350 °F (175 °C) for 20-30 minutes or until a fork goes through easily.