A Curious History of Vegetables: Aphrodisiacal and Healing Properties, Folk Tales, Garden Tips, and Recipes - Wolf D. Storl (2016)

Common Vegetables

Lamb’s Lettuce (Valerianella locusta, Valerianella olitoria)

Family: Valerianaceae: valerian family

Other Names: corn salad, field lettuce, little valerian, mâche, vineyard lettuce

Healing Properties: cleanses blood, regulates bowel movements, prevents infection; prevents spring fatigue

Symbolic Meaning: green life energy that withstands winter and death, a light bringer, an attribute of the goddesses Persephone, Brigit, and Freya

Planetary Affiliation: Saturn

Lamb’s lettuce is surprisingly new as a garden vegetable. John Gerard (~1545-1612), an English herbal doctor who lived in Shakespeare’s time, wrote in his 1597 Herball, or Generall Historie of Plantes of his astonishment at seeing foreigners—Dutch and French living temporarily in England—sow “lamb’s lettuce” in their gardens and harvest it during the time of fasting. His was the first official mention of the plant being cultivated. He was astonished because to him lamb’s lettuce was a prevalent wild plant; though the shiny, lush little rosettes were valued in soups and salads, it was nonetheless just one of countless field weeds. It grew in fallow fields, between stubbles in grain fields, and especially in vineyards or grape orchards. It was even called “vineyard lettuce” in many regions, and was gathered by the basket. It didn’t need to be sown any more than one would sow dandelion, sour dock, or watercress. It was a gift of goodly nature. (Today, except for in the dry, western states it can be found growing wild all over the United States.)

Though it was a latecomer to the cultivated garden, lamb’s lettuce has been eaten for thousands of years. Prehistorians found seeds of the small plant in excavation sites of Neolithic and Bronze Age lake dwellings on Lake Constance, Lake Zurich, and other Alpine lakes. Botanists assume that the plant was originally native to the entire Mediterranean region and Caucasia, and that when Neolithic swidden farmers crossed the Alps to settle in the North they carried their seed and livestock with them. Incidentally they also brought the seeds of agricultural weed species, including the nut-like seeds of corn lettuce.

Returning to John Gerard’s observation: lamb’s lettuce was first taken into garden cultivation toward the end of the seventeenth century in central and western Europe. French settlers later brought the plant to North America; in the early 1800s Thomas Jefferson cultivated it in his garden in Virginia. Its mildly nutty tasting leaves were especially valued as a winter lettuce, when other lettuces are rare. A spot in a president’s garden was certainly a step up for what others had deemed mere weeds.

Illustration 44. Lamb’s lettuce was once sacred to the goddess Persephone (motif from a Greek vase in Gerhard Bellinger, Knaurs Lexikon der Mythologie, 1989)

Of course, the concept of “weed” is a rather modern category; for most shifting cultivators and simple planters the wild companion plants in the fields played an important role as healing plants, psychedelics, spices, and as nutritional supplements in soups and salads. It was usually believed that they were under the protection of certain gods, spirits, or totems, and that they had a prominent place in the rituals and cult practices of the cultivators. Now, lamb’s lettuce is neither a healing or psychedelic plant, but it has a significant asset—even in cooler climates, it grows abundantly in the winter. As a lettuce that could withstand frost it had an important task: when the days were lacking in sunlight, it helped to keep the winter demon scurvy at bay. This wretched disease saps the life energy out of the body, loosens teeth, causes gums to bleed, and makes the skin saggy and scabby. The tender yet ever-so-hardy dark leaves can drive off scurvy because they contain large amounts of ascorbic acid. (Ascorbin is a Greek coinage joining a- [not] and scorbin [scurvy].) Ascorbin is better known as vitamin C.

There is much evidence that lamb’s lettuce was dedicated to the White Goddess, the virginal goddess of light that returns from the underworld and brings light and joy to the beings on earth as the days become longer. This radiant, divine maiden, dressed in white, was the muse of the poets, prophets, and healers. The Greeks knew her as Persephone, the Celts as Brigit, and the Germanics as Ostera (“the one who comes radiantly from the East”). Candlemas Day (Groundhog Day) in the beginning of February was originally her holyday. Lamb’s lettuce is sacred to this goddess, as are the first green of springtime, the primroses, the lesser figwort, and cress. She made her appearance in the season that the lambs are born, and one of her attributes is indeed the gentle lamb. European names of the plant suggest the connection: such as the French laitue brebis, or, in parts of Germany, “sheep’s mouth” (Schaufmäule) or “little lambs.” In the Middle Ages it was called “lamb’s pasture,” or pastus agnorum, known as an herb that “lambs like to eat and is fine fodder for them,” as Tabernaemontanus wrote in 1588.

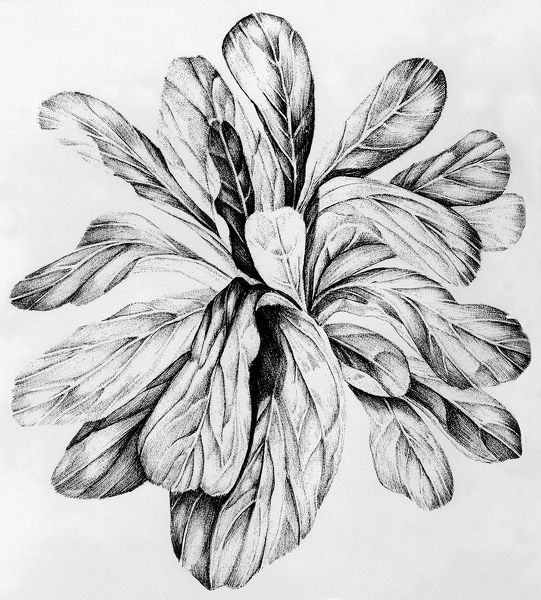

When it first appears in spring the lamb’s lettuce leaves form a shiny, lush rosette. In time a shoot with many branches grows up out of the rosette. Soon after, small, pale whitish-blue blossoms appear, out of which egg-shaped seeds develop. In midsummer the annual plant dies off. Once the plant reaches the flowering stage it’s recognizable as a member of the valerian family—especially recognizable to cats. Many a gardeners has encountered a wrecked bed of lamb’s lettuce after a cat has delightedly wallowed in it. Ethologists believe that the essential oils in valerian-type plants—specifically the iridoid actinidin—affect felines similarly to how natural hormonal attractants do.

As the anthroposophist Rudolf Steiner (1861-1925) emphasizes, valerian plants are light and warmth plants. They have a special relationship to “phosphor processes” in nature. Steiner claims that phosphorus (Greek for “light bearer”) is materialized etheric light and etheric warmth, and categorized valerian as “phosphorus in plant form.” An inherent “phosphorus” effect, the warmth and light radiation, in lamb’s lettuce keeps the rosettes fresh and green despite snow and cold. On a subtle material-energy level it is this same radiation that makes the plant so attractive to warmth-loving cats. (According to Steiner, cats are “phosphorus animals.”)

Illustration 45. Lamb’s lettuce

Just as the cat is especially fond of valerian, the goddess is especially fond of cats—whether that be the goddess Diana of ancient Greece, Durga of India, Isis of Egypt, or Freya of northern Europe. Lovely Freya, who incorporates love and joy, rides across the countryside in a carriage drawn by wild cats. Like the Celtic goddess, Brigit, she was associated with the fresh green of spring. In northern Europe in the spring, in honor of Freya women used to gather fresh green wild plants (“the nine green worts”) and prepare a ritual food out of them in order to reconnect with the rebounding spirit of life and help rid the body of its winter slack. Lush green lamb’s lettuce was always one of these gathered wild plants.

There are many interpretations of the Latin name of lamb’s lettuce. Some linguists believe that Valerianella (little valerian) refers to a rather mystical Roman doctor named Valerius. Others think it refers to the sun god Baldur, or the Roman province Valeria. But it is most likely that the name comes from valere, Latin for “healthy, fit.” This name is very appropriate! Even though lamb’s lettuce is not classified as a medicinal herb, it is extremely healthful. The shiny green leaves are antibacterial, blood cleansing, and “softening”; as such the plant can help regulate bowel movements, as it can soften stool. Lamb’s lettuce contains a lot of bioavailable (absorbable) iron, which serves to build red blood corpuscles, as well as calcium, phosphoric acids, and magnesium. As it contains relatively large amounts of vitamin A, the “little valerian” is beneficial for infections, helping to regenerate dermal tissue and accelerating the building of scar tissue. The previously mentioned ascorbic acid (vitamin C) in the small plant helps prevent spring fatigue, its riboflavin (vitamin B2) provides important digestive enzymes, and its thiamin (vitamin B1) calms nerves and aids in carbohydrate metabolism.

All in all, there’s a lot to be found within this little plant!

Garden Tips

CULTIVATION AND SOIL: Lamb’s lettuce grows well in just about any kind of soil and can be sown from spring to early fall. (Potato farmers, for example, often sow it in the fields after the potatoes are harvested.) In milder climates it can be easily grown all winter long. (LB)

Recipe

Lamb’s Lettuce Salad with Saffron and Strawberries ✵ 2 SERVINGS

SALAD: 4 ounces (115 grams) lamb’s lettuce ✵ 4 ounces (115 grams) fresh green onions ✵ 12 strawberries, halved ✵ SAUCE: 4 tablespoons vegetable broth, cold ✵ 1 tablespoon apple vinegar ✵ 2 tablespoons olive oil ✵ 1 tablespoon parsley, chopped ✵ 1 pinch saffron ✵ cayenne pepper ✵ herbal salt ✵ pepper

Mix the lamb’s lettuce and onions in a salad bowl. In a separate small bowl, mix the vegetable broth with the vinegar and olive oil. Add the parsley. Season to taste with saffron, cayenne, herbal salt, and pepper. Add the strawberries to the sauce; let marinade for about 5 minutes. Gently stir the berry sauce into the salad and serve.

TIP: This dish pairs nicely with freshly baked dark (whole wheat or rye) bread.