A Curious History of Vegetables: Aphrodisiacal and Healing Properties, Folk Tales, Garden Tips, and Recipes - Wolf D. Storl (2016)

Common Vegetables

Fennel (Foeniculum vulgare)

Family: Apiaceae, Umbelliferae: umbellifer or carrot family

Other Names: finocchio, Florence fennel (the bulb used as a vegetable), spignel, sweet fennel

Healing Properties: detoxifies body, prevents convulsions (anticonvulsant), reduces flatulence, inhibits fungi and bacteria, stimulates menstruation (emmenagogue), increases milk production, clears mucus (expectorant), reduces phlegm, calms stomach; beneficial for spleen

Symbolic Meaning: clairvoyance, spiritual clarity; success, victory; transmits cosmic fire, expelling demons. In ancient world attributed to Prometheus and Dionysus; in Christianity associated with St. John and St. Giles

Planetary Affiliation: Mercury

Though fennel was not known until fairly recently as a comestible, this fine, aromatic vegetable is becoming ever more popular. It has a lot of roughage, it improves cellular metabolism, and it’s a diuretic, an expectorant, and a detoxifier. It soothes the intestines and calms the nerves. Eaten raw in salads finocchio (Florence fennel) is a veritable health elixir, one particularly ideal for those working to lose weight. Indeed, the seventeenth-century English doctor William Cole (1626-1662), wrote: “Those who have become fat and indolent use the seeds, leaves, and roots in drinks and soups in order to lose weight and become slim and trim.” When scientists recently tested the effects of fennel oil on mice they discovered that those consuming higher doses lost more weight. Fennel does this by binding lipid substances in the intestines so that the body absorbs fewer triglycerides, which are associated with obesity. Aromatic, yellowish fennel oil has an antiflatulent, antifermentative, antispasmodic effect: it relaxes smooth musculature and also stimulates the flow of bile. Small doses of fennel oil increase discharge in the mucous membranes in the stomach, intestines, and lungs (fennel is often an ingredient in cough medicine). The roots of this biennial, harvested in March of the second year, are regarded by folk medicine—next to parsley, celery, and asparagus—as “cleansing, healing roots.” Anthroposophic doctors emphasize that these effects are typical of the entire apiaceae-, or umbelliferae, family, as they all seem to have either a boosting or an inhibitive effect on the gland system. Warming and relaxing, fennel stimulates the glands.

Illustration 39. Prometheus and the eagle (detail from a drinking vessel, ~540 BC, Greece)

In western Asia and the Mediterranean region—where fennel originated—there are different kinds of wild fennel. They are all characterized by light green, fine filigree, aromatic leaves and yellow umbrella-shaped blossoms, and everywhere they grow they are regarded as sacred and healing. In ancient Greece wild fennel played a central role in the mystery cults. Giant fennel, which grows up to nine feet (three meters) high, was dedicated to Prometheus, the god of fire. This Titan, whose name means “forethinker,” hid the fire he stole from heaven in the stalk of such a fennel plant when he brought it to humankind. (This could be a remnant from primeval memory: archeologists assume that Stone Age foragers of the Mediterranean area carried glowing embers from camp to camp inside dried fennel stalks.) The Greeks believed fennel, a member of the carrot family, improved eyesight. Roman natural historian Pliny the Elder (23-79 AD) claimed that snakes eat fennel after shedding their skin and rub themselves on the stalk so as to renew their eyesight with its juice. Medieval doctors prescribed eye baths with fennel tea, an ophthalmological treatment known to modern-day Egyptian Copts.

The thyros—a wand or scepter that the Greek god of inebriation, Dionysius, used to rule over his enraptured maenads (female followers), satyrs, and sileni—is said to have been made of a fennel stalk decorated with ivy and pine cones. Scholars report that the actors in the Dionysian mystery dramas wore wreaths made of fennel foliage.

Illustration 40. Dionysus on a donkey with a scepter (thyros) (copy of an ancient Greek illustration reproduced in Lexikon abendländischer Mythologie, 1993)

In the ancient Greek language fennel is called “marathón.” Marathon, or “fennel field,” was the name of the location where in 409 BC the Greeks defeated the far more powerful Persian invaders. A messenger then ran forty-two kilometers nonstop to bring the joyous news to Athens, where he shouted before he collapsed and fell dead to the ground, “Victory is ours!” Due to this dramatic incident fennel came to symbolize courage, victory, and success. A marathon-race is still carried out ritually in the Olympic games. Warriors—and later also gladiators—ate fennel or rubbed themselves down with fennel juice in order to succeed in battle and the victors were crowned with aromatic fennel foliage.

The ancients were convinced that evil, disease-causing spirits could be conquered with this strong plant. The physician Dioscorides (~40-90 AD), who was well versed in plant lore, prescribed the marathon plant for bladder and kidney ailments, for nausea and heartburn, for the bites of poisonous animals, as an eye medicine, as a remedy for menstruation irregularities, and “to fill women’s breasts with milk”—all uses that have lasted through to modern day.

For the Romans fennel was of no less importance. The seeds, herbage, and roots of the umbellifer were valued for their healing virtues. Galen (129-~216 AD), founder of humoral pathology, assigned the medicinal properties of fennel as “warm to the third degree” and “dry to the first degree.” The effects were described as warming, diuretic, diluting, widening (for blockage in the glands), dissipating, and loosening. In other words, fennel purifies or purges “bad fluids.” Galen also noted that it increased milk flow and facilitated menstruation.

The Romans valued the plant as a spice and raw vegetable as well. They seasoned vinegar, bread, meat broth, and pickled olives with the seeds, and added the foliage to salads and soups. But even so, though Roman legionaries cultivated fennel as one of their favorite plants in the colonies north of the Alps, it was the Christian monks who established it as a spice and medicinal herb in their cloister gardens. This is partly because fennel was a genuine monk’s medicine, considered an ally in heralding a Christian “spin” on established, “pagan” beliefs; it could stand its ground in the face of the traditional healing plants used by heathen wise women and “wortcunners”: knowers of herbs. It is listed in the St. Gall Cloister Garden layout plans in Switzerland; it appears as well in the ninth-century poem Hortulus, in which monk Walafrid Strabo described the garden he tended. Charlemagne (742-814), untiring conqueror of the heathens, decreed it be planted on all of the royal estates.

Fennel was considered one of the best means of driving off devils and demons; just as it cleanses the body fluids, it also cleanses the astral atmosphere. Like other aromatic herbs—dill, lovage, oregano, thyme, sage, rue—it repels the invisible, swirling astral bodies of wicked witches. Indeed, religious legend claims fennel was one of the herbs that relieved the Savior’s pain as he hung upon the cross. As stated in the tenth-century “Nine Herb Charm (Lacnunga)” of the Anglo-Saxons:

Chervil and fennel, fearsome pair,

These herbs were wrought by the wise lord,

holy in heaven, there did he hang;

He set and sent them in seven worlds

To remedy all, the rich and the needy.

Such a powerful plant soon found a place of honor in Christian folk culture. Fennel became obligatory for seasoning fish in the time of fasting; the poor ate the fasting herb even without fish. Anglo-Saxon laece (leeches, shamanistic healers) brewed a healing potion out of fennel and other herbs as protection against harassment by the devil—which, after Christianization, meant either a figure of a furry, horn-bearing nature spirit or the shaman god Wōdan (Odin). A German folktale claims that the fennel plant is as effective as holy water in driving off nasty dwarves and elves: dangerous figures that not only spook human beings but also inflict pain and disease with their “elf-shots.” In England children wore a sachet with fennel seeds as a necklace to protect them from the evil eye. At the birth of Till Eulenspiegel, a German prankster and magician, the midwife supposedly said: “I bring the lucky child angelica, which protects people from lust; and fennel, which drives the devil away.”

Fennel played also a role in the St. John’s Day celebrations, which were a continuation of old heathen midsummer festivities. Before going to the festival on the village greens, French peasants stuffed fennel foliage into the keyholes of their doors, saying: “In case a magician wants to enter the room through this keyhole, fennel, let him feel your presence and power, so he will be afraid to enter.” Then they could dance and drink with no concern. In the olden days the French also believed that a fennel stalk that’s been drawn nine times through the St. John’s Day fire would protect from magical spells. In England, fennel foliage was hung on doors and windows at the time of St. John. This effective preventative meant witches trying to enter buildings would be forced to count the countless pointed leaves; but as they constantly lost count and had to start over again, their efforts for evil magic proved futile. In East Prussia it was customary to brush the udders and horns of the cows with fennel foliage on the St. John’s Eve (June 23); in Italy the cows’ horns were decorated with it to protect them from the bad spirits that cause disease.

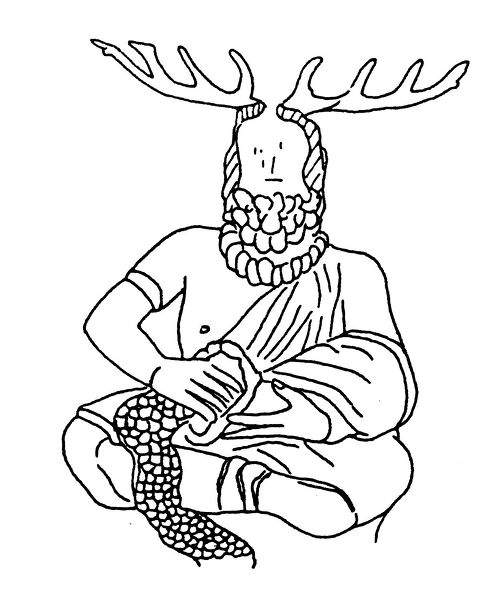

On September 1, the patron day of St. Giles, the Spanish celebrate a regular fennel benediction. In the seventh century St. Giles lived as a pious hermit in a forest hermitage in Provence. There he took into his protection a female deer that had been wounded by hunters. From that day on he became the patron of nursing mothers and milk cows. (Again, fennel, an effective galactagogue, increases the flow of mothers’ milk.) In France, where he is called “St. Gilles,” he replaced the old Celtic god Cernunnos as the “patron of the animals.” For the Germans, too, he became the “patron of fennel”; depending on the region, he is known as Till, Gild, Gill, or Ilg, and is considered one of the “Fourteen Holy Helpers.”

Illustration 41. Cernunnos (etching copied from an ancient Roman relief, Manfred Lurker, Lexikon der Götter und Dämonen, 1984)

Naturally Benedictine abbess Hildegard von Bingen (1098-1179) was also delighted by such a truly “Christian” healing plant that aids both humans and animals. “Feniculum,” she declared, “enlivens people, helps with digestion, gets rid of bad breath, helps as a collyrium (eye-cleansing water) for inflamed-eye conjunctiva, helps as a compress for bad eyesight and headaches, as a smudging plant along with dill for a painful runny nose, as a body rub against melancholy, as a salve for inflamed swelling of the male member, as a warm poultice to ease in giving birth; besides it is also good for lung ailments, strong coughing, heart pain, stomach and intestinal colic, and as a healing means for alcoholism.” She also advised, “An alcoholic should eat fennel foliage or fennel seeds. He will feel better afterward because fennel’s mild warmth and moderate power will tame the madness that the wine has caused.” She might have intended these wise words for monks, often confirmed drunkards. Indeed anethole (anise camphor), one of the main active ingredients in fennel, is thought to detoxify the liver of alcohol poisoning and reduce the effects of snakebites, poisonous plants, and mushrooms.

The “feniculum” Hildegard knew, the “ordinary” Mediterranean healing herb and spice plant, was not the fennel we grow today as a vegetable delicacy. It was not until the Renaissance that Italian master gardeners bred the delicate and popular Florence fennel, or finocchio, with its whitish green, thick, onion-shaped leaf sheaths. Fennel stalks, carosella (F. vulgaris var. azonicum), a popular vegetable in southern Italy, were also developed at this time. The Renaissance was, in fact, a time of glory for this aromatic plant. Nicholas Culpeper (1616-1654), who put fennel under the rule of the planet Mercury and the zodiac sign Virgo, was completely taken by fennel, as was the German herbal doctor Jacobus Theodorus Tabernaemontanus (1525-1590), who filled twelve pages of his 1588 publication Neuw Kreuterbuch describing fennel’s healing properties.

Since that time this “sacred plant of Italy” has spread across the globe, as it prospers in any climate where grapes do well. Today it can be found as an invasive plant growing wild in South Africa, in Argentina, or in California. Presumably European settlers brought the seeds to the Americas, where wild fennel is considered an aggressive invasive plant. In the world of culinary delights, it has become a regular cosmopolitan, serving as seasoning in fish soups and in salads.

Garden Tips

CULTIVATION: The biggest mistake a home gardener can make is to sow a whole row of fennel at once, as the plants will become woody if not harvested quickly. It is best to sow in short intervals, starting in early spring through to early summer—skipping any periods of summer that exceed temperatures of 70° F (24° C), when fennel can bolt to seed. (LB)

SOIL: Fennel prefers neutral soil. If planting in strongly acidic soil, it’s best to mix some limestone into the compost.

Recipe

Fennel Soup with Pesto ✵ 4 SERVINGS

SOUP: 4 fennel bulbs, cut into square cubes ✵ 2 onions, cubed ✵ 3 tablespoons olive oil ✵ ¼ cup (115 milliliters) white wine ✵ 1 quart (945 milliliters) vegetable broth ✵ 2 tablespoons fennel seeds ✵ sea salt ✵ white pepper

PESTO: 5 garlic cloves ✵ 1 tomato, cubed ✵ 1 bunch of sweet basil, leaves picked from the stems ✵ 3 ounces (80 grams) Parmesan cheese, grated ✵ 2 tablespoons olive oil ✵ black pepper

In a medium pan, sauté the fennel and onions in the olive oil. Add the white wine, then the vegetable broth. In a separate pan, roast the fennel seeds without oil on medium heat, constantly stirring or shaking the pan, until they become fragrant but before turning brown. Remove the seeds from the heat and grind them with a mortar and pestle. Stir them into the soup. Season the soup with salt and pepper, to taste. Simmer for about 30 minutes. Transfer to a serving dish.

PESTO: In a blender, mix the garlic, tomato, cheese, and olive oil until smooth. Add pepper to taste. Serve the pesto with the soup.