Growing Beautiful Food: A Gardener's Guide to Cultivating Extraordinary Vegetables and Fruit (2015)

GROW

Chickens, Eggs & Coops

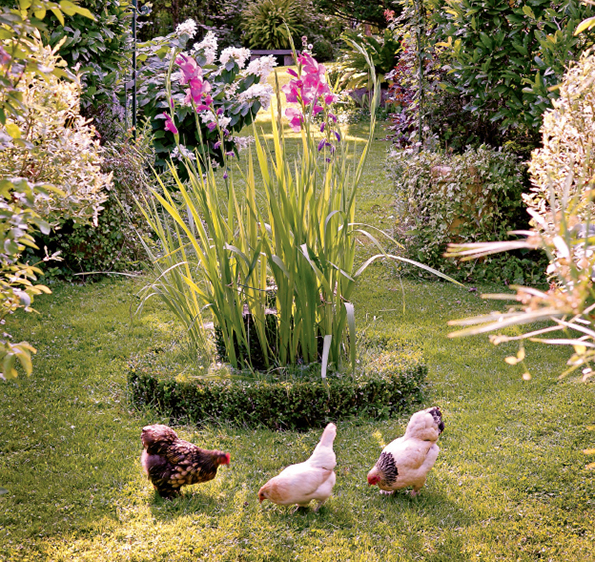

THERE’S NOTHING LIKE A FEW CHICKENS strutting and fretting around the farm to bring the place to life. For all their magic, walking about is something earthbound plants don’t do. Chickens, on the other hand, cluck and peck and flutter like feathered perennials on legs. Brightly plumed and insatiably curious, chickens spend the day foraging for insects, seeds, and scraps; taking long, languorous dust baths; and murmuring praise to themselves for producing one of nature’s truly elegant wonders: the egg.

Freshly laid eggs are a daily blessing at the farm, and a hen in her prime will average one a day. In muted tones of linen white, beach glass blue and green, and deep speckled brown, eggs from your own flock will be the best eggs you’ve ever tasted. Instead of industrial feed, antibiotics, and growth hormones, your flock will be pumped full of all the dynamic life and flavor of free ranging.

They’re also great at keeping pests under control, and their droppings, if left to mellow, will add some serious high-octane nitrogen to your growing beds. Chicken care is pretty basic. Given decent shelter from predators and weather, clean water, and a healthy diet, they’ll take care of the rest, the one caveat being that they might also take care of a few of your precious baby greens or dig a big dust bath in the middle of your bok choy. Chickens may not know a weed from arugula, but a little loss of green seems a small price to pay for the delicious, nutrient-dense eggs you’ll be getting.

Why Chickens?

If ever there were a path to instant farm cred, a fallback to hopping up on your straw bale and shouting “Hey, I’m farming here!” chickens might be it. They clearly send the message that you’re a serious and self-sufficient foodie. And knowing what we know about the wing-on-wing crowding and misery of most poultry farms, keeping a few contented chickens makes a lot of karmic sense. We eat with our eyes and minds as much as we do our tongues, and the sight of a small flock of freely ranging hens clucking about the property, happily creating delicious eggs, is an ongoing delight.

Supermarket birds, even those labeled “free range” and “organic,” are usually fed an unnatural compromised diet, meaning a less varied forage and inferior eggs. Once you’ve tasted poached or soft-boiled perfection from your own flock, with their firm whites and rich orange yolks, it’s hard to settle for less.

We let our chickens range freely in the enclosed orchard, pecking at fallen fruit, digging for seeds and bugs, and dust bathing. This keeps them content and well fed, and—if you believe in karmic gratitude—they thank us with their remarkable eggs.

Chickens have been around for thousands of years, and there are hundreds of recognized breeds. Some are prodigious egg layers, others are bred for their meat, while many are simply ornamental. Bantam breeds are popular for their showy, patterned plumage and small size, a plus when your property is modest. All breeds are egg layers, although bantam eggs are smaller. Breeds come in a dazzling blend of colors and patterns, some with feathered feet, others with fleecy plumes or mop tops. A flock of mixed, multicolored hens is a beautiful garden unto itself.

Whether you allow them to free range or keep them in a coop and run, caring for backyard chickens is relatively easy. As long as they have access to clean water, food, shade, and shelter, they’ll go about their business without much fuss. The rewards of caring for your own feathered flock are many, and you may find yourself bonding with your birds like with any other pet. Their insatiable curiosity and amusing social habits are always entertaining around the home. Besides all their bug-eating and egg-laying benefits, chickens are just plain fun to have around.

Where to Begin?

Be sure to check local ordinances before you decide to raise a backyard flock. Some towns and municipalities don’t allow chickens, while others restrict the size of the flock and whether roosters are permitted. You may also want to let your neighbors know, appeasing any concerns with the promise of fresh, organic eggs.

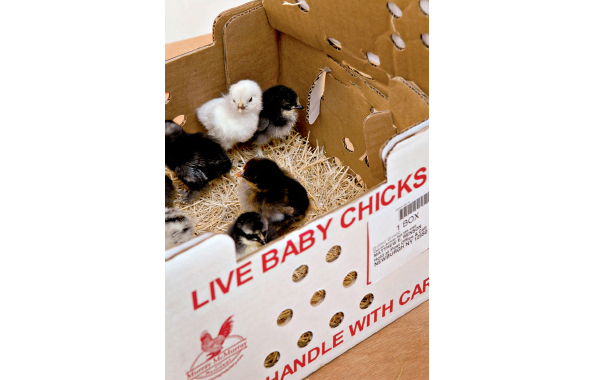

Chicks should be ordered in early spring. They can be bought either at the local farm supply store or from catalogs and online suppliers. Ordering online has the advantage of variety, although most hatcheries require you to order a minimum of 25 chicks, as they come cheeping in the US mail, huddled together for warmth. The least expensive orders are straight runs, which are usually half roosters, half hens. Since a flock needs only one rooster to produce fertile eggs, a “sexed” run of all females and one male is best. If you just want a laying flock and don’t plan on breeding chicks (or if roosters would unnerve the neighbors), order a sexed run of only females.

Chick Care

Your baby chicks will need close attention and care for the first few weeks, so be sure your schedule fits theirs. It’s important to have your brooder box set up before you order. This is an enclosed space for day-old chicks with a water fountain, feeder, and heat lamp. It can be as simple as a large cardboard box with wood shavings or paper towels as bedding, but be sure to change the bedding regularly. The brooder box needs to be draft free and placed somewhere in the house or garage where it can be checked on easily at least a half-dozen times a day (although chicks are so adorably fuzzy and cute you may find that they monopolize your time!).

Baby chicks need a steady heat source for the first few weeks of their lives—95°F (35°C) for the first week, 90°F (32°C) for the second, and so on, reducing the temperature by 5 degrees each week. Keep a thermometer in the brooder to monitor the heat: Extremes in either direction could be fatal. An infrared lamp (250 watts) is a good heat source, and its red spectrum is less disruptive than white light.

Baby chicks can be chaotic and messy when it comes to drinking and eating, so invest in a waterer and feeder designed specifically for them. The waterer should be filled a few times each day, as 95°F and no shade brings on thirst. The feed you’ll need, usually called starter feed, is a finely ground mash, or crumble, that’s medicated to prevent certain diseases in young chicks. You can even feed them the odd bug or two, which they’ll love!

By the second week, your chicks will be strong and curious enough to flap out of their brooder box unless the top is covered with netting or chicken wire. If you find a chick poking around in your sock drawer, you know it’s time to put the roof on.

Once your chicks are a few weeks old, and if it’s warm enough outside, you can bring them out for a little romp in the garden. Be sure they have access to water and shade and protection from drafts and predators. Until fully grown (and their sharp beaks are at eye level with the family cat), they’re on everyone’s meal plan.

Housing

Before you consider keeping chickens, determine where your chicks will live after they leave the brooder, because you’ll need to have your housing ready for shelter and egg laying. Ideally, it’s in partial shade in summer and has access to electricity for a winter heat lamp and water warmer. The closer to your home the better in order to keep an eye out and to make egg harvesting more convenient.

Standard breeds will need at least 1½ cubic feet per bird, while bantams will need 1 cubic foot. Coops can be stationary structures with access to a run so the birds can get outside, or you can let them out each day to free range on your property. Just remember that foraging birds are unprotected from predators (everything from hawks, raccoons, and coyotes to the family dog), so there’s risk in letting them range. We’ve lost a few hens to hawks, taken out by a swift set of talons in broad daylight. Chickens are easy to spot from above—a fluff of life against a monotony of grass, and not much of a match for a hawk’s silent wings and its keen, focused hunger. Aside from keeping chickens enclosed in a run or pen, however (which would counter our free-range philosophy), there’s really no protecting against a determined predator from above. If you are small and yummy and out under the open sky, they will have you.

Another option is a movable coop, or chicken tractor. These usually have a coop on top, with an enclosed run underneath. This can be moved to a new spot in the garden every other day, where there’s new turf for them to scratch and nibble. Moving your chickens around your property in a protected coop keeps them safe, gives them access to a varied diet, and evenly fertilizes your lawn.

NOTES FROM THE WONDERGROUND

Don Juan Draper

We ordered a sexed run of baby chicks in February, meaning all female (you don’t need a rooster to have eggs), and one of the Ameraucanas had always seemed a bit mannish—less chat and gossip, more heavy lifting—so I had my suspicions.

Then suddenly, a strident, piercing yodel, and all the aloof and indomitable maleness that follows. I’ve had to assert my alpha to his beta, of course, but the fluttering harem is his. Now the crow is all day long, a sexual marathon of carping because he just can’t get enough. (Meanwhile, we can easily get an oeuf from our teenage harpies without him, thank you very much.)

We’ve called the newly outed rooster Don Draper, after the oversexed drunk on Mad Men, and to stay on theme, our little covey of Peking ducks are Joan and Peggy. The rest of the hens are just flirty, egg-laying extras, hoping Don will offer them a drink and a shag.

I’m of two minds about roosters. They’re more imperious and beautiful than the hens, so points there for my meddlesome camera and me, but the noise and the rough sex are alarming—like a neighbor with multiple clients in cuffs and leather. There’s also not a lot of sweet feathered courtship or foreplay. It’s all frenetic, sexual hop-scotch (or would that be Kentucky bourbon for Don?).

Having a rooster around is an encounter with maleness at its most primal: all the territorial machismo, the rampant, brutish polygamy, the female subjugation. But it’s best not to project onto nature. She has her reasons. It’s only when we intervene and skew the balance that the trouble begins.

Mornings are the busiest for Mr. Draper. He wakes with a few good crows, then romps through the orchard, downing dead cicadas for protein and a few stray berries for breath, before going on the prowl, coming on to whatever bit of fluff will have him.

Because he’s still such a callow lover, he hasn’t yet learned the slow, copulatory waltz of chicken wooing: one wing down and extended, a rhythmic rattle and sway around the hen. His efforts are graceless and awkward, like any teenager.

For the hens, who are still learning to master the submissive come-hither crouch, this is just the laying before the laying. Let Don Juan Draper have his moment, then it’s on to the important business of making eggs or domestic squabbling over roosts and worm scraps.

Don is a future king. Though still too slight of crown and feather, he will enter his prime in the next year, a princely young cockerel to be reckoned with.

It’s breakfast in the orchard for Mr. Draper, then on to woo a few ambivalent hens under the apple trees. Regardless of his efforts at fertilization, the eggs will continue to be laid and harvested in abundance.

The coop will need to have certain essentials to keep your hens happy. A clean, ventilated space is important, with plenty of fresh bedding (either straw or untreated wood shavings). You’ll need nesting boxes, usually one for every three or four hens, a waterer (the larger the better), a feeder, and somewhere for chickens to roost. At night, chickens will want to roost on the highest spot in the coop, but make sure your roosts are not over the feeder or waterer or the device will be fouled by droppings.

An outlet in your coop is a good idea. Just be sure it has a protective outdoor-rated cover on it. A fan can be run in summer if temps are too hot, an infrared heat lamp and water warmer turned on in winter. The heat lamp can be set on a timer to go on at night when temperatures drop. This will keep the coop comfortable and also keep the hens laying, as light triggers a hen’s ovulating cycle. Hens will lay an average of one egg a day, so be sure to harvest regularly.

Because chickens are creatures of habit and like to roost and nest in the same spot every day, when you first move your month-old chicks to their new coop, give them a few days to imprint that this is their home. Begin by letting them free range only a few hours each day, then gradually increase their free time. This will keep them from getting lost or ending up in a neighbor’s tree.

Maintaining the Flock

Chickens are social creatures and love to strut about together, chattering and pecking at bugs and dirt. They will watch out for each other and holler loudly when danger is near. They’ll also squabble over eggs and nesting boxes, over roosts, or over some particularly tasty morsel. If a rooster is part of the flock, he’ll tend to keep things in order, but chickens will fight over hierarchy regularly. (Ever hear of “pecking order”?)

A chicken’s needs are pretty basic, but you will be responsible for meeting them. If they are sheltered with enough clean food and water and space, they will thrive. You will need to clean out the coop of droppings regularly (every month or so) or use a deep litter method, where at least 6 inches of straw or shavings are laid down and changed twice a year. This bedding can then be added to compost piles or tilled into the soil as an excellent nitrogen source.

Chickens love routine. To them, any change is loss, even the good changes. What they covet are the daily patterns of language they’ve learned since cracking out of the egg. Give them repetition, monotony even, and they seem content.

Chickens will begin laying at around 20 weeks. Once they do, you will need to change their feed to layer pellets or layer crumbles. These supply the extra protein that hens need to lay. You can also supplement their regular feed with a tossing of scratch (a mix of corn and other grains) once or twice a day, but don’t overdo it; this is a treat, not a staple. Your birds will also need grit, since chickens don’t have teeth. They store coarse grit in a crop in their neck where it mashes their food like teeth. Grit can be bought from your feed supplier and mixed in with their feed. Or if your birds are free ranging, they’re likely to ingest bits of stone or coarse sand on their own.

Chickens are über-omnivores: They’ll sample, trial, and taste almost anything, even chicken (don’t ask). They love scraps from the kitchen, and the more variety they eat, the better your eggs will taste. They love leftover rice and pasta, vegetable and fruit scraps, and greens. Avoid giving them citrus, onions, garlic, potato peels, bread, and meat. Generally, they know what’s good for them, but it’s best not to encourage a mistake.

They will get into all and everything, of course: raspberries, blackberries, tomatoes. I’ve watched them leap 3 feet in the air to snatch a raspberry, or balance on a tightrope of orchard wire to snack on currants, or peck incessantly through fencing to reach a tomato. They will also go after your greens, unraveling the beds into loose stitches, or decide, without much discretion, that your planting of fall spinach is a fine spot to take an afternoon siesta, so you find your coddled greens flattened here and there by the imprint of a settled hen. Just when a long-awaited apple, pear, or tomato is heavy with itself, it’s pecked into nothingness. Prevention with netting and fencing will do wonders to keep your chickens in check.

There’s no question that adding chickens to the garden ties us to another time, when they were an integrated part of domestic life. A farm livened up with the flutter and bustle of chickens—not to mention their usefulness—becomes a bigger, more fulfilling place.

Health and Diseases

Although there are many problems that can affect chickens, it is entirely possible to maintain a small flock without a hitch. Start with healthy birds from a reputable source, have them vaccinated for Marek’s disease (a highly contagious viral infection) before shipping, and offer them what they need to maintain their good health and vigor.

Given good nutrition, ample water, access to fresh air and exercise, protection from predators, and shelter that is clean, dry, and well ventilated, chickens can be reasonably trouble-free.

Provide food and water in containers that let the flock eat and drink without allowing them to foul the feed or water by standing in it. Keep the coop clean and change the straw or other bedding regularly to keep it fresh and dry. Good sanitation, applied regularly, keeps the proportions of the task manageable and avoids the buildup of droppings and moisture that can allow molds and bacteria and associated respiratory problems to develop in the flock. Many problems arise from keeping chickens in crowded, dirty conditions, so it’s vital to keep the coop clean.

Make sure there is enough room at the feeders and waterers for all chickens to gain access, and design the space to be comfortable and secure. Crowding, overheating, or other stressors can prompt chickens to pick at themselves or at the rest of the flock. The picking out of a few feathers can escalate quickly into a free-for-all of pecking and plucking that often leads to bloodshed. As soon as you identify an episode of picking, separate injured chickens from the rest of the flock. Offer a few handfuls of greens or other treats to distract the aggressors from the undesirable behavior. Clean wounds and apply an antipick material such as pine tar (sometimes called Stockholm tar), dilute vinegar, or dilute Listerine before reintroducing birds that have been “picked on” back into the flock.

Various species of lice and mites may infest chickens during their lives, inflicting various levels of irritation and distress. Dust baths are chickens’ natural way of easing their discomfort and ridding themselves of tiny biting parasites, but populations of pests can sometimes escalate beyond the birds’ ability to dust them away. Prevent external parasites with good sanitation. Keep wild birds from building nests in the chicken coop. Paint wood surfaces in the coop, including roosts and nest boxes, with linseed oil, and apply lime to the chicken run annually. Including cedar chips in the bedding material can help deter mites.

The intestinal disease coccidiosis is caused by parasitic protozoans. Chickens ingest the parasite eggs in fecal matter in soiled litter. Warm, wet conditions increase the risk of infection. Good sanitation, such as keeping the litter clean and dry (but not dusty) and moving waterers around to avoid consistently wet areas, helps minimize coccidiosis. Chickens often host a few of the protozoans that cause coccidiosis without developing symptoms and can develop resistance to the disease, which tends to be most harmful to young birds. A few breeds of chickens are resistant to coccidiosis.

Most important, get to know the individual chickens in your flock and be familiar with their normal routines and behaviors. Make a habit of spending a few minutes observing each one daily. Besides being entertaining, this makes it easier to recognize when something’s amiss with a member of the flock. Many common diseases first appear as listless behavior, reduced eating and drinking, and unkempt feathers. If you are uncertain about a diagnosis or unsure how to treat a bird’s symptoms, seek professional advice. Spotting a problem early lets you isolate a sick chicken and increases the likelihood that proper care can restore a chicken to health and prevent illness from spreading through the entire flock.

Keeping Chickens Safe

Free-ranging chickens in open space also opens them up to dangers. A determined and hungry fox, coyote, raccoon, weasel, or hawk will be a challenging adversary for your flock.

A hawk on the hunt is a magical, ominous sight: its silent wings cutting loose, slow wheels of menace across the sky. If you can hear the high-pitched kee-eeeee-arr of a hawk, you know your chickens have heard it too (chickens are genetically programmed to fear this sound), and they’ll be warily seeking any cover they can find. They’ll crouch under brambles or join the songbirds that have muted themselves in thickets. All the mad, flitting bustle of life on the farm will come to an abrupt stop. The best defense is to try and herd chickens (like you’d herd cats) back into the coop and keep them in until the danger passes. Alternatively, you can make sure that they have a place to scurry and hide under when danger lurks, either a dense hedgerow with plenty of thorny brambles (blackberries are great for this, and this is where my birds hide when they’re out in my orchard) or some other protective structure. You can build a simple twig and bramble teepee for chickens to scurry to when they’re out in the open.

If you have a rooster, he will be a great help in protecting the flock and will alert them to danger. (Besides fertilizing eggs and flustering hens with his inexhaustible libido, flock protection is his business.) Hawks are bold and fearless and will not be deterred by your presence. We once lost a young Brahma hen that was foraging about 20 feet from us. A hawk swooped down silently from a perch where it had been keenly waiting, grabbed the terrified hen, and loped off with her, barely able to get off the ground. We found her later in a back field, her body opened like a book, with an assembly line of eggs still waiting to be hatched.

The best alternative to complete free ranging is to put in a sizable run (at least three times the square footage of the coop) with welded wire fencing around it that either goes into the ground a foot deep or skirts out a foot below the fenceline to keep digging predators from getting under your run. The top of the run can either be roofed or covered in netting or wire. Our run is covered in netting and clambered over by a vigorous grape vine, which adds shade and some support for the netting during snow. It’s also great snacking for chickens when the grapes ripen.

Raccoons can be a particular challenge to flock security. They can rip through chicken wire as though it were a bag of pretzels and can even open latches with their dexterous hands. Double locks on the coop doors and hardware cloth over the windows will work as a reasonable deterrent.

In order for chickens to maintain their health, it is important that they get a rich and varied diet from forage. If you don’t want to let them out to free range for fear of predators, you can bring in a daily supply of compost, weeds, and scraps. Scatter it in the run so that the chickens can dig through it to supplement their diet. Alternatively, you can range a small flock using what’s known as a “chicken tractor.”

Resources

There are many places to purchase chickens, from day-old chicks to year-old pullets. Feed stores and local farms will usually have chicks in spring, and online classifieds like Craigslist often offer chickens for sale right in your neighborhood. As backyard chickens have become increasingly popular, the number of online suppliers has skyrocketed. Purchasing through the Internet will offer the most choice of varieties and breeds, as well as supplies, although feed is best bought locally because of its weight. Some reliable Internet suppliers include Murray McMurray Hatchery (mcmurrayhatchery.com), Ideal Poultry (idealpoultry.com), and Privett Hatchery (privetthatchery.com). From large breeders, you will need a minimum order of 25 chickens, so splitting an order among a few people will work if 25 is too many. Smaller orders can be purchased from My Pet Chicken (mypetchicken.com) and Meyer Hatchery (meyerhatchery.com).

NOTES FROM THE WONDERGROUND

Magical Realism

It turns out our dizzy, mop-topped hen, Phyllis Diller, is actually Phil S. Diller, a transgender cockerel. He went from dulcet murmuring to an all-out strident crow in the space of a week. Give him some Spandex and he’s like a relic from an ’80s hair band.

Chickens are full of peculiar surprises, but this one I didn’t see coming. We put him on Craigslist, and a very nice couple from Connecticut adopted him. Apparently they’re into leather.

A new flock of fuzz (all female, I’ve been assured) arrived via the post office today. The promise of fresh farm eggs, along with these beautiful, warm April skies, has put dance back in our winter-weary bones here at Stonegate Farm.

Pulling a warm egg from beneath a broody hen is a magical thing: the ruffled murmur as she relinquishes; the egg’s perfect, spherical warmth, its bone-smooth promise. And fitting so perfectly in the palm of the hand, as though the relationship between laying and gathering always was.

Compared to a supermarket dozen, and to the USDA’s nutrient data on commercial eggs, our orchard-roaming hens will produce a vastly superior product. Their natural, free-range diet—including seeds, berries, insects, and greens, along with grain—will result in eggs with far less cholesterol and saturated fat and much higher levels of vitamin A, vitamin E, beta-carotene, and omega-3 fatty acids. Is it any wonder they taste better?

Even chickens labeled “free range” and “organic” at the Stop & Shop are usually fed a compromised diet of soy, corn, and cottonseed meal, laced with additives, with limited or no access to the outdoors. Jailbirds, basically.

When a new CSA member stopped by this week to say hello, I was unprepared for the power and imprint of memory that took hold on her visit. She had grown up on a farm in Iowa, and her connection to that time seemed to rill through her as we did our walkabout.

On the way out, we visited the hens in La Cage aux Fowl and, on putting a warm, just-laid egg in her palm, she began to cry softly. Clearly, the evocation was almost too much. There was some awkward silence as she held the egg—and her childhood—in her hand and struggled for composure. But she seemed grateful for the experience and what it summoned up.

There’s something in our collective genome that ties us to a past when farming and growing food were everywhere and everyone took part. For most people, the relationship between a meal and its source was immediate. If I can offer up the occasional connection, how wonderful. If a farm can serve as a common metaphor for connecting to our past, our food, our deeper responsibilities to the planet, so be it.

Chickens come in all shapes and sizes, from fanciful bantams to plain but productive layers.