The Encyclopedia of Spices and Herbs: An Essential Guide to the Flavors of the World - Padma Lakshmi (2016)

SPICES, HERBS, AND BLENDS FROM A TO Z

C

PREVIOUS SPREAD, CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT: cloves, Chinese five-spice powder, coriander, cinnamon, curry leaves, cassia (ground), cilantro, chaat masala, Chinese black cardamom, cumin, chives, Colombo, celery seeds, cassia, caraway, green and white cardamom, and chervil

CARAWAY

BOTANICAL NAME: Carum carvi

OTHER NAMES: siya jeera, Persian caraway, Roman cumin, wild cumin; shahi jeera, sajira (black caraway)

FORMS: whole seeds and ground

CARAWAY TEA Add 1 to 2 teaspoons crushed caraway seeds to 1 cup boiling water and steep for 10 to 15 minutes, then strain.

Caraway is a biennial herb native to Asia and northern and central Europe. A member of the same family as parsley, it is an ancient plant, and evidence of its culinary use dates back to 3000 BC. Today, the Netherlands is the largest producer; caraway is also grown in Scandinavia, Germany, Poland, Russia, Canada, the United States, Morocco, and northern India.

The small, ridged, curved brown seeds—the split halves of the plant’s fruits—are pointed at the ends. They have a warm, very pungent aroma that is like a combination of the aromas of dill and aniseed and a tangy, nutty flavor. Black caraway seeds are darker and thinner and they have a flavor of cumin that is not found in regular caraway; in fact, they are sometimes referred to, erroneously, as black cumin. Both caraway and cumin may be called jeera or zira in India; adding to the confusion is the fact that the Swedish name for caraway is kummin.

Caraway is harvested in the early morning, when the dew is still on the plants—once dried by the sun’s warmth, the seedpods will shatter, dispersing the precious seeds onto the ground below. The plant stalks are allowed to dry and further ripen for about ten days, then threshed to remove the seeds. Ground caraway loses its fragrance fairly quickly, so it’s best to purchase whole seeds, which are easy to grind if first toasted in a dry skillet.

Caraway is used predominantly in Europe and the Middle East. It pairs well with cabbage (notably in sauerkraut), fruits such as apples, and pork. It seasons myriad sausages, and it is found in many European cheeses. Caraway seeds are used in European breads such as rye bread and the French pain d’épices. They are also found in some versions of the spice blends ras el hanout, garam masala, and harissa. In the Middle East, a dish made with caraway called moughli is served to celebrate childbirth. Black caraway, which is native to Persia, is used in northern India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh, where it adds its distinctive rich, nutty taste to biryanis, kormas, and some Moghul-style and tandoori preparations. Caraway’s essential oil flavors liqueurs such as aquavit, kümmel, and schnapps.

MEDICINAL USES: Considered a digestive, caraway can be used to make a soothing tea (see sidebar). The seeds, though bitter, can be chewed (preferably after being toasted) to relieve an upset stomach.

TOASTING SPICES

Toasting spices brings out their flavor and fragrance. The easiest way to do this is to dry-roast them in a cast-iron or other heavy skillet: Heat the pan for a minute or two over medium heat, then add the spices and toast, shaking the pan frequently to prevent scorching, for 2 to 3 minutes, or until very aromatic; depending on the spices, they may turn a few shades darker. Immediately transfer the spices to a plate or bowl to cool, so they don’t burn in the hot skillet. It is best to toast spices whole and then grind or crush them if desired; ground spices will toast unevenly and are much more likely to burn.

CARDAMOM

BOTANICAL NAME: Elettaria cardamomum

OTHER NAMES: green cardamom (see below for brown and red cardamom)

FORMS: pods, whole seeds, and ground

Cardamom is a tropical perennial bush in the ginger family native to southern India and Sri Lanka. It is also grown in Vietnam, Guatemala, and Tanzania. It is one of the most expensive spices in the world, a fact explained in part by its relatively limited growing area and the laborious harvesting process. Cardamom is called the queen of spices in India (pepper is the king), and the best green cardamom comes from Kerala.

Cardamom is harvested by hand just before the fruit is ripe—if left to mature, the pods will split open and the seeds will be scattered and lost. Because the pods do not all ripen at the same time, harvesting takes place over several months, with skilled workers choosing only those pods that are ready. The best cardamom is dried in special sheds heated by wood-fired furnaces rather than under the hot sun, which would bleach the pods.

Green cardamom pods are about half an inch long and contain twelve to twenty dark brown to black seeds that may be oily or somewhat sticky. Cardamom has a warm, sweet fragrance with delicate citrus and floral top notes and a refreshing undertone of eucalyptus. The seeds are aromatic, with a floral scent and a fresh, lemony flavor. Look for bright green pods. White cardamom pods have been bleached and should generally be avoided, although white cardamom is used in some Indian desserts where the green color would be undesirable. When used whole, the pods are usually cracked before being added to a stew or other dish. Some recipes call for the whole seeds, but they are more often ground; the seeds are best ground in a spice grinder. If buying ground cardamom, note that it should be a fairly dark brown; lighter powders are made from ground whole pods and are of lesser quality, as the husks have little flavor.

Cardamom is used in a wide variety of savory and sweet preparations. It features prominently in Indian, Persian, Turkish, and Arabic cuisines, in stews, curries, and biryanis and other rice dishes; it is also used to season vegetables. It is an essential ingredient in garam masala, and it is found in many other spice blends as well, including baharat and ras el hanout, and in curry powders. It flavors many Indian sweets and desserts, including kulfi and rice pudding, and it complements poached pears and other fruits. Cardamom pairs well with sweet spices such as cinnamon, allspice, cloves, and nutmeg, and in Scandinavia, it is used in cakes, cookies, and Danish pastries. In the Middle East and North Africa, cardamom often flavors the coffee served after a meal; it is also added to tea. Since cardamom is a stimulant, it was used in love potions in mythology.

Black cardamom (sp. Amomum subulatum), also called brown cardamom, is not true cardamom; its many common names include bastard cardamom and false cardamom. Also known as Bengal cardamom, Nepal cardamom, and winged cardamom, it is valued for certain preparations. The dried oval pods, which are much larger than those of regular cardamom, are dark brown, ribbed, and rough, and they can contain as many as fifty seeds. The pods have a smoky, woody aroma, and the seeds have a camphorous fragrance and taste, with slightly sweet notes. Black cardamom is used whole, usually crushed, or finely or coarsely ground in certain Indian meat and vegetable dishes, especially more rustic or spicier preparations.

Chinese black cardamom (sp. Amomum costatum), also known as red cardamom, is a different species, grown in southwestern China and in Thailand. The large dark-reddish-brown pods, which can be 1 inch long or more, are ribbed and sometimes still have the stems intact. They have a strong, spicy flavor and, unless dried in the sun, a gentle smoky flavor from the drying process. Chinese black cardamom is popular in Szechuan and other Chinese regional cuisines and in Vietnamese cooking. The hard pods are added whole to slow-cooked dishes, such as braises, and to steamed rice or soups. The ground seeds are sometimes added to stir-fries.

CAROM/CARUM

See Ajowan.

CASSIA

BOTANICAL NAMES: Cinnamomum cassia (Chinese), C. burmannii (Indonesian), C. louririi (Vietnamese), C. tamala (Indian)

OTHER NAMES: false cinnamon

FORMS: sticks, pieces, and ground

Cassia comes from the bark of a tropical evergreen that is related to the bay laurel tree. It is native to Indonesia and, according to some sources, also to northeastern India. The Cinnamomum family includes dozens of members; C. zeylanicum is considered “true cinnamon” (see Cinnamon). Like cinnamon, cassia is an ancient spice, and its history dates back centuries. It has been cultivated in China since 4000 BC, and it was an important part of the spice trade. The major producers of cassia today are Indonesia, China, and Vietnam; it is cultivated in India, too, where the leaves of the tree are also used as a spice (see Cassia Leaves).

Cassia is harvested at the beginning of the rainy season, when it is easiest to remove the bark from the trees. The bark is cut off in large sections; depending on the region, the coarser outer bark may be scraped off before the cassia is dried in the sun. As it dries, the bark, which is thicker than cinnamon bark, curls into what are called quills; cassia is also sometimes sold as small flat pieces. Once dried, cassia turns a dark reddish-brown; its color is darker than that of cinnamon. Although the quills, or sticks, can be used whole, the bark is very hard and difficult to grind at home, so much of the crop is ground commercially. Ground cassia is also darker and redder than ground cinnamon. Cassia has a warm, sweet fragrance similar to that of cinnamon but less intense; the flavor is stronger than that of cinnamon, mildly sweet but with a bitter undertone. Saigon, or Vietnamese, cassia has a higher oil content and a more pungent taste than the other cassias on the market.

Although it is illegal to label cassia as “cinnamon” in some countries, no such distinctions are made in the United States, and in fact, the cinnamon found in almost all supermarkets is actually cassia, most of which comes from Indonesia. In North America, cassia cinnamon is a favorite ingredient in cookies, spice cakes, and other baked goods and desserts. In many other countries, however, it is more widely used in savory dishes. In India, cassia—often as whole quills—seasons curries, rice, and vegetables. In Malaysia and Southeast Asia, it is used in savory stews and rice dishes. Cassia is also one of the ingredients in Chinese five-spice powder and the Middle Eastern seven-spice mix (see Baharat).

MEDICINAL USES: Cassia has been used in traditional medicine to treat a variety of ailments, including stomachaches and other digestive problems. It is considered an appetite stimulant and is valued for its antioxidant properties.

CASSIA LEAVES

BOTANICAL NAME: Cinnamomum tamala

OTHER NAMES: Indian bay leaves, tej patta, tejpat

FORMS: fresh and dried

Cassia leaves come from the tree, native to northern India, that is the source of cassia cinnamon (see Cassia); it is in the same family as the species that is the source of our familiar bay leaves. The shiny dark green leaves are much larger than bay leaves and each one has three prominent veins running down its length, rather than the single vein of bay leaves. The aroma and taste are mildly cinnamony, with a hint of cloves. Cassia leaves are widely used in Indian cooking and in some Asian cuisines, more often dried than fresh. They are added to Indian curries, stews, and rice dishes and to Moghul-style biryanis, kormas, and vegetable pulaos. The leaves are also used in Kashmiri and Nepalese cooking, and they are infused to make an herbal tea in Kashmir. Cassia leaves are one of the ingredients in garam masala.

MEDICINAL USES: Traditional medicine ascribes antibacterial, antifungal, and anti-inflammatory properties to cassia leaves. An infusion of cassia leaves is sometimes prescribed for an upset stomach and other digestive disorders.

CELERY SEEDS

BOTANICAL NAME: Apium graveolens

OTHER NAMES: wild celery, smallage

FORMS: whole and ground

CELERY SALT Combine 3 parts salt and 2 parts ground celery seeds. Dried parsley and/or dill can be added for more flavor.

Native to eastern and southern Europe, the celery plant that supplies the familiar seeds is a descendant of wild celery, or smallage, which was used for medicinal purposes in ancient times. Related to parsley, it’s a biennial that is now grown throughout Europe, including Scandinavia, and in North America, North Africa, and northern India.

Celery seeds are tiny and practically weightless—there are close to half a million seeds in one pound. The curved ridged seeds, which are, in fact, split halves of the plant’s fruits, are light to dark brown in color, with a penetrating aroma like that of stalk celery. They have a strong, warm, somewhat bitter flavor, although they are far less bitter than the seeds of their ancestor smallage. Cooking reduces the bitterness and enhances the sweetness of the seeds.

The seeds are usually used whole because they are so small, but crushing them will make them more aromatic. If they are ground, they should be used fairly quickly, as the flavor is fleeting and the bitterness will become more pronounced. The seeds are also ground for celery salt, which sometimes contains dried herbs such as parsley and/or dill (see Celery Salt).

The flavor of celery seeds complements tomatoes particularly well, and the spice is found in many tomato and vegetable juices (and, of course, in Bloody Marys). Celery seeds are also used commercially in ketchup, pickles, and numerous spice blends, particularly those for poultry and meats. They are often added to salads or coleslaw or sprinkled over bread doughs before baking. In Scandinavia and parts of Russia, celery seeds are added to soups and sauces. They also season various Indian curries, especially tomato-based ones, and pickles and chutneys.

Caution: Celery seeds are used to make restorative infusions and tonics in India, but these should not be taken by pregnant women or anyone on blood pressure medicine or diuretics.

CEYLON CINNAMON

See Cinnamon.

CHAAT MASALA

Chaat (sometimes spelled chat) masala is a ubiquitous Indian spice blend, used to season everything from meat and vegetables to fresh fruit and salads. A typical mix includes amchur (mango powder), cumin, coriander, mint, ginger, chile pepper, ajowan, asafoetida, anardana (dried pomegranate seeds), cloves, salt, and—one of the defining ingredients—Indian black salt. It’s a pungent, hot, sweet, salty mix made sour by the mango powder. Most popular Indian street foods, referred to as chaat, are seasoned with this blend.

CHAIMEN

See Armenian Spice Mix.

CHARMOULA

See Charmoula and Other Spice Pastes.

CHERVIL

BOTANICAL NAME: Anthriscus cerefolium

FORMS: fresh and dried leaves

A member of the parsley family, chervil is an annual native to eastern Europe. Sometimes called garden chervil to distinguish it from other varieties, the herb looks something like a cross between a fern and parsley, with delicate, wispy leaves. Its flavor is also delicate, with slight anise notes reminiscent of tarragon and undertones of parsley. The flavor of the dried leaves is muted, and they should be added in generous amounts to a dish toward the end of cooking; chervil, whether fresh or dried, does not stand up well to heat. Look for dark green leaves when buying dried chervil and avoid any hints of yellowing, which indicates age or improper storage.

Chervil is essential in French cuisine but little used in cooking elsewhere. It is particularly good in scrambled eggs and omelets—it is one of the ingredients in the herb blend fines herbes, often used in egg dishes. It pairs well with fish and shellfish and is used in light cream sauces. It also complements spring vegetables such as peas, early carrots, and asparagus.

CHILES

BOTANIC NAMES: Capsicum annum (also spelled annuum), C. frutescens, C.chinense, C. baccatum, C. pubescens

FORMS: whole dried chiles, dried chile flakes, and ground dried chiles (pure chile powder)

All chiles are native to Latin America, particularly Mexico, and the West Indies, though they are now found around the world in tropical and temperate climate zones. Their history dates back to 7000 BC, and they were probably first cultivated in Latin America not long after that. But they were unknown beyond their native regions until Columbus took chiles back to Spain—and they then traveled throughout Europe and into Asia. Columbus thought chiles were related to Piper nigrum, the climbing vine that is the source of pepper, and because of that confusion, chiles are often referred to as peppers. The name chile comes from the Nahuatl word chilli—and the spelling still varies today, depending on the country, with chili being another form. Mexico remains a major producer, along with India, China, Thailand, Indonesia, and Japan.

Several hundred varieties of chiles have been identified, and the plants cross-cultivate and hybridize easily. Capsicum annum is the most common species, with C. frutescens second to that; some sources believe that these two originally came from the same species. (Other less-common species are listed above.) C. annum is an annual, and most chile plants are grown that way, but C. frutescens is more often cultivated as a perennial. Capsaicin is the compound that gives chiles their heat, and it is most concentrated in the ribs and seeds of the fruits. Generally, smaller chiles are the hottest ones and larger chiles less hot, but there are exceptions. The heat of a chile also varies depending on the climate, soil, and other factors—and sometimes even chiles from the same harvest will vary in hotness.

Chiles are green when immature and will ripen to red, yellow, deep purple, orange, brown, or almost black, depending on the variety. They may be harvested when green or fully ripe. Dried chiles, whatever their locale, have traditionally been dried in the sun, either on mats or concrete slabs, or sometimes simply on flat rooftops. They are often left to cure out of the sun for several days before drying begins, and they are usually covered at night during the drying process (not unlike vanilla beans). Another traditional way to dry chiles is to tie them into ristras, or garlands, or wreaths and hang them in the sun. While the traditional methods persist, today many chiles are commercially dried.

Chiles are used in cuisines around the world, from Mexico to the Mediterranean and Africa to Asia. They feature in salsas and hot sauces, spice pastes, and table condiments, and they season innumerable dishes. Although chiles are always associated with heat to one degree or another, they can also add complex flavor, and good cooks in any country choose their chiles carefully. Below are some of the most popular dried chiles, along with a number of more unusual varieties. (Note: As this is a book about spices and herbs, the focus is on dried chiles; other common chiles, such as jalapeños, that are best or only used fresh are not covered here.)

THE SCOVILLE SCALE

In 1912, Wilbur Scoville, a chemist, devised a test to determine the perceived heat of chile peppers, which became known as the Scoville Organoleptic Test. Capsaicin is the compound that gives chiles their heat, and Scoville based his test on the amount of capsaicin per chile. Chiles were rated according to Scoville Heat Units, with bell peppers ranking 0, jalapeños ranging from 2,000 to 5,000, and superhot peppers like habaneros registering from 200,000 to 300,000 units. However, his test was based on taste and hence is a subjective one. A more modern test used by the scientific community employs a high-pressure liquid chromatograph (HPLC), which is far more reliable. Its results are given in ASTA (American Spice Trade Association) units, but Scoville’s name is so ensconced in memory that these are often converted to Scoville units. Nevertheless, the heat of a particular chile can vary depending on growing conditions and a variety of other factors, and so results and rankings can vary greatly as well, with some sources, for example, giving a range of from 2,500 to 10,000 for jalapeño peppers. In this book, we use a simple scale of 1 to 10 to rate the heat of the chiles.

AJÍ AMARILLO (C. baccatum, sometimes identified as C. chinense; heat level: 7 to 8 on a scale of 10)

Native to the Andes, the amarillo chile is most widely used in Peru. Amarillos are usually more orange than yellow (despite the fact that amarillo means “yellow” in Spanish), and the dried chiles are orange. They are about 4 inches long and narrow, with a pointed tip. Despite their heat, they have a fruity flavor. The fresh chiles are often made into a paste that seasons a variety of dishes; dried amarillos are usually used in sauces. The dried chile is also sometimes known as ají mirasol.

AJÍ PANCA (C. baccatum, sometimes identified as C. chinense; heat level: 1.5)

Panca chiles are widely grown along the Peruvian coast and are a staple of Peruvian cuisine. They are about 5 inches long and 1 to 1½ inches wide. They ripen to a deep burgundy color, and the dried chiles are wrinkled and almost black. Panca chiles have only mild heat and a sweet, fruity, berry-like flavor. They are used in stews, fish dishes, and sauces.

ANCHO (C. annum; heat level: 3 to 5)

The ancho, the most popular dried chile in Mexico, is a dried poblano. It’s a larger pepper, 4 to 5 inches long, and broad-shouldered (ancho means “wide” in Spanish). It’s usually deep red when dried but can be darker, and it is sometimes confused with the mulato chile; it is also, confusingly, called a pasilla chile in parts of Mexico. Good-quality ancho chiles are still flexible, not completely dried. They have a fruity flavor and they tend to be on the milder end of the scale but can sometimes be surprisingly hot.

TOASTING AND SOAKING DRIED CHILES

Many recipes call for toasting dried chiles before using them, to bring out their flavor; the heat will often also soften the chiles slightly. Heat a large cast-iron or other heavy skillet over medium heat until hot, then add the chiles and toast, turning them once or twice, until fragrant, about 2 minutes. Remove from the heat.

Dried chiles are generally rehydrated before using. Put the chiles—toasted or not—in a deep bowl and add very hot water to cover. Let soak for 20 to 30 minutes, until softened. Often the chiles are then pureed in a blender (with or without other ingredients) with enough of the soaking water to give the chile paste or puree the desired consistency.

BIRD’S-EYE CHILE

This name can apply to any of a variety of small hot chile peppers, but it is most commonly applied to a type of Thai chile.

BYADGI (C. annum; heat level: 6)

These chiles come from the town of Byadgi in the Indian state of Karnataka, in the southwestern part of the country. The dried chiles are around 2 inches long and bright to dark red. Like Kashmiri chiles, they are valued for the color they impart to the dish in which they are cooked, as well as for their fruity flavor and moderate heat, and, in fact, they are sometimes misidentified as Kashmiri chiles (and vice versa). However, they are noticeably thinner than the Kashmiri (they are sometimes referred to as kaddi, which means “stick-like”). Byadagi chiles are widely used in the cooking of South India.

CALABRIAN (C. annum; heat level: 3 to 4)

These chiles come from Calabria in southern Italy, a region known for its chile peppers. In fact, there are numerous capsicums grown there, but most of them are simply called Calabrian chiles. The dried chiles are deep red and usually 2 to 3 inches long. The red pepper flakes found in any pizzeria in Italy, called peperoncini, are usually from dried Calabrian chiles. American chefs cooking Italian food have recently become enamored of Calabrian chiles and are using them in many dishes. The dried chiles are also sold packed in oil.

CAROLINA REAPER (C. chinense; heat level: 10)

For the moment, at least, the Carolina Reaper holds the title for the world’s hottest chile. It dethroned the Trinidad Scorpion in 2013, with a Scoville rating that averages 1,569,000 units but is sometimes as high as 2,200,000. The Carolina Reaper is a cross between a ghost chile and a red habanero. The dried chiles are about 1 inch long, wrinkly, and dark red. Proceed with caution!

CASCABEL (C. annum; heat level: 4)

The cascabel is a small round chile that gets its name from the way the seeds rattle inside the dried chiles—cascabel is the Spanish word for “rattle.” It is also sometimes called chile bola (ball chile). The chiles are about 1½ inches in diameter, thick fleshed, and dark reddish brown. They have a slight smoky-sweet flavor and a nutty taste, which is accentuated when the chiles are toasted.

CAYENNE (C. annum; heat level: 8)

Most North Americans know cayenne chiles only in their powdered dried form, but the chiles—there are many different varieties—are grown in India, Asia, and Africa, as well as in Mexico, and they are especially popular in Indian and Asian cuisines. Cayenne chiles also grow in Louisiana and South Carolina, and they are widely used in Cajun and Creole cooking, and in hot sauces. The dried chiles are bright red, from 2 to 6 inches long, and narrow, with smooth skin—and very hot.

CHILCOSLE (C. annum; heat level: 5)

These chiles are a relative of the Mexican chilhuacle rojo (see below) and are also native to Oaxaca; their name is sometimes spelled chilcostle. They are about 5 inches long, fairly narrow, and often curved. They are thin fleshed and aromatic. Like chilhuacles, chilcosle chiles are most often used in moles and other cooked sauces.

CHILHUACLE (C. annum; heat level: 3 to 5, depending on the type)

Chilhuacle chiles come from southern Mexico—specifically the regions of Oaxaca and Chiapas—and are not often seen in the United States. They are thick-fleshed medium chiles, and there are three varieties: amarillo (yellow), negro (black), and rojo (red). Most are about 2 to 3 inches long, but some are more tapered than others. Amarillos have broad shoulders tapering to a point; they are reddish-yellow when fresh and dark red or almost brown when dried. They have a tart taste with some sweetness. Negros are squatter and look something like small bell peppers; they are a deep mahogany when fresh and a darker brown when dried. They have an intense flavor with notes of licorice. Rojos are red when fresh and a mahogany color when dried. They have a rich, fruity, sweet taste. All these chiles have complex levels of flavor, and they are most often used in the mole sauces that are the hallmark of Oaxacan cooking.

CHIPOTLE (C. annum; heat level: 5 to 6)

Chipotles are dried jalapeños, though other fresh chiles can be treated in the same way. The chiles are picked when ripe and smoke-dried. The larger chipotles also known as chiles mecos are brown and very wrinkled; they are 2½ to 3½ inches long and about 1 inch wide. They are hotter than the typical green jalapeño, since they have ripened on the plant, and they have a fruity, smoky-sweet flavor. Mora and morita chiles are smoke-dried jalapeños, though moritas in fact may also be dried serrano chiles. Moras are slightly smaller than chiles mecos and moritas are just 1 to 2 inches long; some cooks think moritas have the most complex flavor. Chipotles are often sold canned en adobo, a sweetish, tangy tomato sauce.

COSTEÑO (C. annum; heat level: 4 to 7, depending on the type)

Costeños come primarily from the coastal areas of the Mexican states of Oaxaca and Guerrero (costeño means “coast”), and the chiles, which are usually dried, are little known outside their native regions. The dried red costeño, costeño rojo, also referred to as chile bandeño, is related to the guajillo chile. It is about 3 inches long, narrow, slightly curved, deep red, and quite hot, registering 6 to 7 on a scale of 10. The less-common yellow costeño, costeño amarillo, is bronze or amber in color when dried. It is usually less spicy than the red costeño, with a heat level of about 4, although it is sometimes hotter. It has a more complex flavor than the red costeño. It is used in some versions of mole amarillo.

DE ÁRBOL (C. annum; heat level: 7.5)

Also known as bird’s beak chiles, these are one of the most popular dried chiles. The name de árbol means “from the tree,” or “tree-like” in Spanish, and the bush that produces them can develop woody stems like a small tree. The bright red chiles, a close relative of cayenne peppers, are 2½ to 3 inches long, thin, and curved; the dried chiles range from bright to brick red. They are thin fleshed and very hot, with a smoky flavor. They are a good choice for chile oils or vinegars. The whole or ground dried chiles are used to season sauces, stews, and soups.

DUNDICUT (C. annum; heat level, 7 to 9)

These small chiles are indigenous to Pakistan, the major producer today. They are thin fleshed, round or tear shaped, and ½ to 1 inch in diameter. The dried chiles are scarlet and slightly wrinkled. Their heat level varies, but they can be very hot; along with heat, they add a fruity flavor to sauces, curries, and other dishes. Dundicuts are often compared to Scotch bonnet chiles, but they are not as hot.

GHOST CHILE (C. chinense/frutescens hybrid; heat level: 10)

Native to Bangladesh, the ghost chile was declared the world’s hottest chile (from 850,000 to more than 1,000,000 Scoville units, depending on the harvest and the source of the ranking) in 2007, but there are more recent contenders for the title; see Trindidad Scorpion, and Carolina Reaper. In India, its names include naga jolokia and bhut jolokia; it is also referred to as Tezpur chile, for the region in northeastern India where it grows. The dried chiles are 1½ to 2 inches long, wrinkled, and red to dark reddish-brown, with thin skin. Obviously they must be used in moderation.

GUAJILLO (C. annum; heat level: 2 to 4)

The guajillo is the most common chile in Mexico. It is about 5 inches long and 1 inch or so across; the dried chile is deep red to mahogany in color, smooth, and shiny. The heat can vary from mild to fairly hot and the flavor is fruity but somewhat sharp. It is a thin-fleshed chile, and the skin can be tough, so sauces made with guajillos should generally be strained.

GUINDILLA (C. annum; heat level: 6 to 7)

These chiles are popular in Spain, especially in the Basque region. Long, curved, and thin, they are thin fleshed, with moderate heat and an underlying sweetness. Dried guindillas are used in Basque dishes identified as al pil pil, meaning “with chiles,” such as bacalao (salt cod) or gambas (shrimp) al pil pil.

JAPONÉS (C. frustescens; heat level: 5 to 6)

Native to Mexico and used in Latin American and Caribbean cooking, these widely grown chiles are also cultivated in Japan and season many Japanese and Chinese dishes. The dried red chiles are about 2 inches long, narrow, and thick fleshed; some sources suggest substituting chiles de árbol for japonés chiles if they are unavailable, though de árbol are thinner fleshed and less meaty. Japonés chiles tend to have more heat than complexity of flavor. They can be used to make a spicy chile oil.

KASHMIRI (C. annum; heat level: 4 to 6)

From India’s northernmost state, this chile is sometimes used as much for the color it imparts to any dish as for its fruity flavor and its heat, which is moderate. The thin-fleshed chiles are around 2 inches long, tapering to a pointed tip, and dark red and wrinkled when dried. They are often soaked in hot water to soften them and then ground to a paste before using, but they can also simply be dry-roasted until fragrant and added to a soup, stew, curry, or tomato sauce. Dried Kashmiri chiles are also available powdered, but be aware that the spice sold as “Kashmiri chile powder” is frequently a blend of different chiles, often not even from the region—check the label carefully.

MALAGUETA (C. frutescens; heat level: 7 to 8)

The malagueta is a hot chile from Brazil, and it is beloved there and in Portugal and Mozambique. It is sometimes called Brazilian hot pepper; it should not be confused with the Melegueta pepper from Africa’s western coast, the source of grains of paradise. The dried red peppers are fairly narrow and range from ¾ inch to 2 inches long; the smaller ones are sometimes called malaguetinha or piri piri peppers (piri piri is a name given to several different small dried chiles; see here). Malagueta peppers are the base of many Portuguese and Brazilian hot sauces (sometimes labeled “piri piri sauce”). They are used in stews and marinades in Brazil, Portugal, and Mozambique, and they are a favorite seasoning for chicken. (Also see the spice blend known as piri piri.)

MULATO (C. annum; heat level: 3 to 4)

The mulato is a close relative of the poblano and the dried chile is similar to the ancho. Ripe mulatos have medium-thick chocolate-brown flesh and are around 5 inches long and 2 to 3 inches wide at their broad shoulders. The dried chiles are a very deep brown and wrinkled; their flavor is sweet, with notable smoky notes and a hint of chocolate. Mulatos are one of the chiles used in some classic mole sauces, notably the famous mole of Puebla.

NEW MEXICO (C. annum; heat level: 3 to 4)

There are several types of chiles called New Mexico chiles, many of which are cultivars developed at New Mexico State University. The most common dried New Mexico chile is a large red chile also called chile colorado (colorado means “red” in Spanish) or California chile. It is thin fleshed and dark red when dried; it is usually 6 to 7 inches long and about 1½ inches wide at its broadest point. Its heat is on the milder side but noticeable, and its flavor is earthy and somewhat fruity. Dried New Mexico chiles are used in many sauces and often processed into chile flakes or powder.

PAPRIKA

See here.

PASILLA (C. annum; heat level: 3 to 5)

The pasilla chile is a dried chilaca pepper. It is dark brown to black, and it is also called chile negro (black chile). The word pasilla means “little raisin,” referring to the chile’s color and very wrinkled skin. Pasillas are thin-skinned, about 6 inches long by 1 inch wide, and slightly curved. The flavor is fruity, and the heat is medium to hot. Pasilla, ancho, and mulato chiles are known as the “holy trinity” for the classic mole sauces of Puebla.

PASILLA DE OAXACA (C. annum; heat level: 6 to 7)

These chiles are virtually unknown outside Oaxaca and parts of Puebla. They are sometimes called chile mixe, because they are grown in the Sierra Mixe. The chiles are picked when ripe and then smoked. The smoked dried chiles are deep red. They have a fruity, very smoky flavor, and are quite hot. They range in size from 1½ inches to 3½ or 4 inches long and are about 1 inch wide, tapering to a rounded or pointed tip. Larger ones are often stuffed, while the medium chiles are pickled. The small chiles are usually reserved for table (i.e., uncooked) salsas. These chiles are an important ingredient in Oaxaca’s mole negro. Rarely seen outside their native region, they are worth seeking out.

PIQUÍN (C. annum; heat level: 6)

The name chile piquín (or pequín) is given to a variety of small chiles in Mexico; they are also called bird peppers. They are usually no more than ½ inch in length and are often smaller, but they are quite hot. The dried chiles are deep red to reddish-brown and thin fleshed; the flavor is smoky, with an undertone of citrus. Ground dried piquín chile is a common seasoning in Mexico, served as a condiment for pozole and other soups and stews and used as a garnish for salads and even some sweet drinks. Elotes, the popular street food of roasted corn that is slathered with mayonnaise and coated with grated cotija cheese, is typically finished with a sprinkling of ground piquín chile.

PIRI PIRI (C. frutescens; heat level: 8)

The chile known as piri piri, or peri peri, in Africa is native to South America, but it grows widely, both wild and cultivated, all over the African continent. Piri is the Swahili word for “pepper”; the chile is also sometimes known as the African Red Devil pepper or African bird’s-eye pepper. The dried chiles are red, less than 2 inches long, narrow, and very hot. They are used to make hot sauces and in many traditional dishes.

PUYA (C. annum; heat level: 5 to 6)

The puya chile, also spelled pulla, is closely related to Mexico’s guajillo chile. It is 4 to 5 inches long and narrow, tapering to a sharp point (the word puya means “steel point” in Spanish). The dried chiles are deep red and spicy, with a fruity heat.

TEPÍN (C. annum; heat level: 8)

Also called chiltepín, the tepín chile is a wild piquín chile found in Mexico and the American Southwest, although both tepín and chiltepín may be used to refer to any piquín chile in different parts of Mexico. The tepín is another bird pepper, very small but very hot. The chiles are about ¼ inch in diameter, thin fleshed, and red or reddish-yellow when dried. They are sometimes infused to make chile vinegar.

THAI (C. frutescens, C. annum, C. chinense; heat levels vary)

A number of different chiles belonging to several species grow in Thailand and while they range in size and color, most are hot, some searingly so. One of the most common is the small red chile often referred to as Thai bird’s-eye chile, or simply bird chile. In terms of heat, it registers 8 to 9 on a scale of 10. It is widely used in other Southeast Asia cuisines as well. The dried chiles are added whole to stir-fries and other dishes and also used in sauces.

TIEN TSIN (C. annum; heat level: 9)

These chiles are native to Tientsin Province in China, and they are also referred to as Chinese hot chiles. One to two inches long and narrow, they resemble cayenne peppers. The dried chiles are bright red to scarlet and very hot. They are used in many Hunan and Szechuan dishes and are popular in other Asian cuisines as well. Because they are so hot, they are often removed from a stir-fry or other dish before serving. A spicy chile oil made with Tien Tsin peppers is used for stir-frying or as a table condiment.

TRINIDAD SCORPION, BUTCH T STRAIN (C. chinense; heat level: 10)

The Trinidad Scorpion deposed the naga jolokia, or ghost chile, as the hottest chile in the world in 2011, with a heat level of 1,463,700 Scoville units. However, its reign was brief—see Carolina Reaper. It is a cultivar native to Trinidad and Tobago. The dried chiles are ¾ to 1 inch long and dark red; the pointed bottom tip of the pepper is said to resemble the stinger of a scorpion, hence the name. The chiles have a pungent aroma and are searingly hot—use in moderation, perhaps to flavor a big batch of cooked salsa. Bottled hot (very hot) sauces are sometimes made with scorpion chiles.

WIRI WIRI (C. chinense; heat level: 6 to 7)

This hot chile from Central America has a variety of names, including bird cherry pepper, hot cherry pepper, and Guyana cherry pepper; the “cherry” part of the name obviously comes from its round shape and small size. It is particularly popular in Guyana, although it is used elsewhere in Central America and in the Caribbean. The dried chiles are about ½ inch in diameter, wrinkled, and red or reddish-yellow in color. The chiles can be reconstituted in warm water before being used, but they are fairly brittle and can simply be crumbled between your fingers or crushed and added to a simmering stew or sauce.

RED PEPPER FLAKES

The RED PEPPER FLAKES [4] found on the grocery-store shelf—and in pizzerias—are most commonly crushed dried cayenne chiles, but other peppers, or a mix, may also be used. Beyond the familiar supermarket jar, however, there are a number of more exotic choices for adding heat and chile flavor to your dishes. Chile flakes from Turkey and Syria are increasingly appreciated in the West, and four types are described below, along with the Korean pepper flakes called gochugaru.

The ALEPPO [3] chile is named for the city of Aleppo in northern Syria, close to Turkey’s southern border. The city is also called Halab, and the pepper is sometimes called Halaby pepper. The bright red coarsely ground pepper does not contain any seeds; it is often processed with salt and olive or sunflower oil, giving it a salty taste and a moist, clumping texture. It has mild to moderate heat and a very fruity flavor. Aleppo pepper has traditionally been used throughout the Middle East, especially in regions along the eastern Mediterranean, and in Turkey. Unfortunately, the worsening political situation in Syria means that Aleppo pepper production has suffered and the chile flakes are difficult to find.

The MARAS [5] chile comes from the town of the same name (also called Kahramanmaraş) in southeastern Turkey, which is quite close to Aleppo, and the pepper has a similar flavor profile. The bright red red pepper flakes, which may be coarse or relatively fine, have a fruity taste and medium heat. Maras (also spelled Marash) chiles have a high oil content, but oil and/or salt is often added during processing, and the chile flakes are moister and oilier than the typical dried red pepper flakes.

The URFA [1] chile also comes from southeastern Turkey, near the Syrian border. Named for the town of Urfa, or Şanlıurfa, it is sometimes called Iost pepper. The chiles darken to almost a deep purple-black during the drying and curing process. Urfa chile flakes have a complex, somewhat fruity flavor, with undertones of smoke; they are often processed with salt, which complements their natural sweetness. Like the other chiles of the region, the peppers have a high oil content, and the pepper flakes are quite moist and can clump easily; as with those other chile flakes, olive oil is often added. The chile flakes are fruity and moderately hot, with a lingering heat. Most Urfa chiles are processed into chile flakes, so the whole chiles are rarely seen in the marketplace.

The Turkish KIRMIZI [2] chile is actually a blend of hot and milder dried chiles; Kirmizi biber translates simply as “red pepper.” Oil and salt are added to the chile flakes during the curing process, and they are fruity, sweet, and moderately hot.

Korean red pepper flakes are called GOCHUGARU [6], or kochukaru. The coarse flakes are bright red and their heat can range from mild to moderate. The heat level may be indicated on the package: maewoon means “very hot,” while those labeled deolmaewoon will be milder. They are an essential ingredient in kimchi, the spicy pickled vegetable condiment, most often made with cabbage, that is found on any Korean table. These chiles were traditionally dried under the sun, and the best versions are still sun-dried.

CHINESE ANISE

See Star Anise.

CHINESE BLACK CARDAMOM

See Cardamom.

CHINESE CHIVES

See Chives.

CHINESE FIVE-SPICE POWDER

Star anise is the dominant flavor in this well-known Chinese spice blend; the other spices are cassia cinnamon, cloves, Szechuan pepper, and fennel seeds. Some mixes also contain ginger, cardamom, licorice root, and/or dried orange peel. The powder may be fine or more coarsely ground, and the color ranges from reddish brown to tan. Five-spice powder is used throughout southern China and in Vietnam, as well as in some other Asian cuisines. It is good with fatty meats such as duck and pork. Many traditional Chinese “red-cooked” dishes are seasoned with five-spice powder. It is used both as a dry rub for roasted poultry and meat and in marinades. Fragrant and spicy, the powder should be used sparingly, to avoid an overpowering flavor of star anise.

CHINESE PARSLEY

See Cilantro.

CHIVES

BOTANICAL NAMES: Allium schoenoprasum; A. tuberosum (garlic chives)

OTHER NAMES: Chinese chives (garlic chives)

FORMS: fresh and dried or freeze-dried chopped leaves

Chives are an allium, a member of the family that also includes onion, garlic, and leeks. Regular chives, occasionally referred to as garden or onion chives, are native to central Europe; garlic chives, also called Chinese chives, are indigenous to Central Asia. Unlike other members of the allium clan, chives have almost no bulb, and only their long, thin leaves are eaten. Garden chives have long, bright green, hollow leaves, and their flowers, which are also edible, resemble pale purple or mauve pom-poms; garlic chives, which can be slightly taller, have flattened pale-green stems and white flowers. Both have a more delicate flavor than other alliums, garden chives leaning toward onions in flavor, and garlic chives, not surprisingly, toward a more pronounced garlicky taste.

Fresh chives are used in many cuisines, but dried chives are almost as ubiquitous—particularly so since the advent of freeze-drying, which preserves their flavor and color much better than traditional methods. Most dried chives are garden chives, and freeze-dried chives will indicate that process on the label. Chives are very good in egg or cheese dishes, creamy white sauces, and salad dressings. They are one of the ingredients in the classic French herb blend fines herbes, and they are often combined with other herbs. They should be added near the end of cooking in most cases, to make the most of their flavor. Garlic chives are used in a variety of classic Chinese and other Asian dishes.

CILANTRO

BOTANICAL NAME: Coriandrum sativum

OTHER NAMES: coriander, Chinese parsley

FORMS: fresh and dried leaves

Cilantro is an annual herbaceous plant indigenous to southern Europe and the Middle East. It is valued for both its fresh growth and its seeds, which, unusually, have a very different aroma and taste from the leaves; for more on the history and background of cilantro, which is sometimes referred to as fresh coriander, see Coriander.

Cilantro has bright green leaves that bear a certain resemblance to flat-leaf parsley, which accounts for one of its common names, Chinese parsley. But it is not related to parsley—it is a member of the carrot family—and its flavor is distinctive. It also seems to be divisive: although many people love cilantro, others think it tastes like soap. (According to some recent studies, an intense distaste for cilantro may actually be genetic.) Aficionados, however, find its unusual fresh, citrusy flavor addictive. Like most tender herbs, cilantro is best used fresh, added at the end of cooking to preserve its flavor. Dried cilantro has little fragrance, but high-quality dried leaves can impart something of the unique flavor of the fresh herb when added shortly before serving and allowed to “blossom” in the heat or steam radiating from the dish.

Cilantro is widely used in Latin American, Caribbean, and Asian cuisines; the stems and roots, as well as the leaves, are added to many dishes. Mexican fresh salsas and guacamole are flavored with cilantro, as are ceviches in Peru, Mexico, and other countries. Cilantro is the Spanish word for coriander, and this may be why it is now used to describe the fresh leaf of the plant. It has a particular affinity for black beans and other beans. Its flavor is also good with hot chiles, and it is used in spicy stews and soups in Mexico and in curries, stir-fries, and other dishes in India and Southeast Asia. It is used as a garnish for lassis and the chopped salads called kachumbers, as well as made into chutneys in India and herb pastes in Thailand and other Southeast Asian countries, often in combination with garlic and/or chiles. Cilantro also pairs well with ginger, lemongrass, and mint, all signature flavors of Thai cuisine.

CINNAMON

BOTANICAL NAMES: Cinnamomum verum, C. zeylanicum

OTHER NAMES: Ceylon cinnamon

FORMS: quills and ground

True cinnamon comes from the bark of a tropical evergreen tree, a member of the laurel family, native to Sri Lanka. It has a long and venerable history, and it was known in the time of the pharaohs and in ancient Greece and Rome. It is mentioned in the Torah, and it was one of most sought-after commodities in the early days of the spice trade. Today, Sri Lanka is the main producer, and its cinnamon is believed to be the best. Cinnamon is also cultivated in other tropical regions, particularly the Seychelles. (See Cassia for information on other members of the large Cinnamomum genus.)

The bark of the tree is harvested during the rainy season, when it is moist and easier to remove. “Cinnamon peelers” are highly skilled, and often several generations of the same family will be involved in the harvests, each generation learning proficiency from the one before it. Workers first cut the small branches, or shoots, from the trees and scrape off the coarser outer bark. Then the thin inner layers are cut and painstakingly rolled into scrolls, or “quills,” and allowed to air-dry, protected from the sun. When the bark is processed, smaller pieces, called quillings, often break off, and these are inserted in the quills as the peelers form them. Quillings that break off as the cinnamon dries are used for ground cinnamon. Cinnamon bark is thinner and more brittle than cassia bark, and the fragrance is more delicate as well. The aroma is warm, sweet, and agreeably woody, and the taste is equally warm. Unlike cassia, cinnamon bark can be ground at home in a spice grinder. The quills are paler than cassia quills, and the powder is pale tan rather than reddish-brown.

Cinnamon is one of the most common spices used for baking, from cookies to cakes and pies to sweet breads, and for other desserts. Whole quills are often added to the poaching liquid for pears and other fruits, and they are traditional in mulled wine. Cinnamon sugar is sprinkled over cookies or other baked goods. Cinnamon also has a wide variety of uses in savory dishes. Many Moroccan tagines are flavored with cinnamon, as is bastilla (there are many variants of this name), the savory phyllo-dough pastry stuffed with a filling of chicken, ground almonds, and rose water or orange flower water. Cinnamon flavors biryanis and other rice dishes, as well as meaty stews and curries, throughout the Middle East, India and Pakistan, and Malaysia; it is a favorite seasoning for lamb in many cuisines. Cinnamon is an ingredient in garam masala, ras el hanout, and many other spice blends.

MEDICINAL USES: Cinnamon has long been part of traditional medicine in Asia and India, and it was used for medicinal purposes in ancient Egypt as well. It is believed to help cure gastric upsets and is often prescribed for colds and other respiratory ills.

CLOVES

BOTANICAL NAME: Eugenia caryophyllus

FORMS: whole and ground

Cloves are the unopened flower buds of a tropical evergreen tree native to the Moluccas (aka the Spice Islands) in eastern Indonesia. They were an important part of the early spice trade (Columbus was looking for the Spice Islands when he landed in the West Indies). Their name comes from the French word clou, meaning “nail,” because of their appearance, with a rounded head and tapered stem. Indonesia remains one of the largest producers, and the trees are now grown in Sri Lanka, Madagascar, Tanzania, and Grenada as well.

Cloves are harvested by hand, and the trees must be at least six years old before the first harvest, though they will then continue to bear fruit for fifty or so years longer. There are two yearly harvests, and the process requires a delicate touch. The buds are gathered when they have reached full size but have not yet opened, and they do not all reach the proper stage at the same time, so the pickers have to be discerning when choosing which clusters of buds to harvest. Then the buds are removed from the stems, again by hand, and dried in the sun for several days.

Dried cloves should be dark reddish-brown, though the bud end, which is surrounded by four “prongs,” will be somewhat lighter. They are pungent and highly aromatic, warm and slightly peppery. The taste is strong, even medicinal, warming, and sweet; if chewed, cloves leave a lingering numbing sensation on the tongue. Good-quality cloves may release a small amount of oil if pierced with a fingernail. When purchasing whole cloves, avoid jars or packages with many noticeable stems, which have far less of the volatile oil than the buds. Ground cloves should be dark brown; a lighter color is an indication that the mix includes ground stems as well and is of a lesser quality.

Cloves are used in Middle Eastern, Indian, and North African cooking, in rich or spicy meat dishes, including Moroccan tagines, and in some curries, and they enhance many rice dishes. With their strong flavor, they should always be used sparingly. When the dish is served, the whole cloves may be removed or not, but they are generally not consumed. A clove-studded onion is often added to chicken stock as it simmers. Cloves are used in baking in Europe and North America, and in poached fruits and mulled wine. They combine well with many other spices, especially warming ones, and they are an ingredient in numerous spice blends, including garam masala, quatre épices, baharat, and berbere.

MEDICINAL USES: Cloves have been valued for medicinal purposes since ancient times, as a painkiller, among other uses (clove essential oil is still used to treat toothaches). They are also believed to alleviate intestinal distress, and they can be chewed as a breath freshener.

COCUM

See Kokum.

COLOMBO

OTHER NAMES: poudre de Colombo

Colombo is the name given to West Indian curry powders, specifically in Martinique and Guadaloupe; the blends are many and varied. Curry arrived in the Caribbean with immigrant workers from India in the mid-nineteenth century, and the name comes from the capital of Sri Lanka, Colombo. A basic mix consists of cumin, coriander, fenugreek, peppercorns, and mustard seeds; many blends include the decidedly non-Indian allspice, which is native to the Caribbean. Others may also include cardamom, ginger, cloves, turmeric, and/or ground dried bay leaves, and while some do contain dried chiles, others do not, as the dishes the blend is used for tend to include fresh chiles. In the West Indies, poudre de Colombo seasons curries made with goat, lamb, chicken, pork, or beef, as well as fish and vegetables. It is also used as a rub for grilled fish and meats.

CORIANDER

BOTANICAL NAME: Coriandrum sativum

FORMS: whole seeds and ground

A member of the carrot family, coriander is an annual plant native to the Mediterranean region, specifically southern Europe and the Middle East. It is an ancient spice, with a history dating back more than three thousand years; it is mentioned in the Bible and in Sanskrit texts (and in The Arabian Nights). It was one of the first spice plants grown in North America. Primary producers today include India, the Middle East, Central and South America, the United States, Canada, North Africa, and Russia.

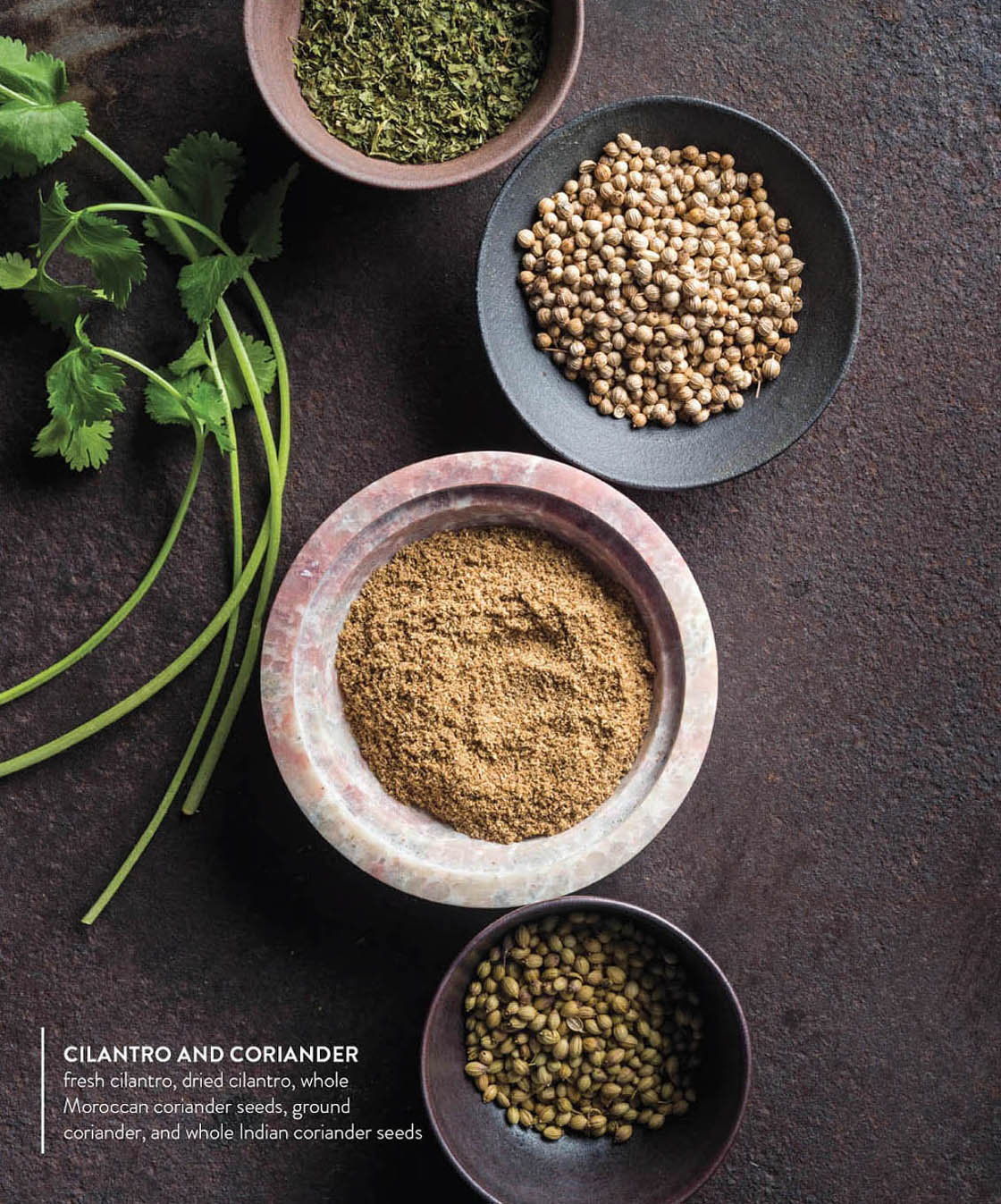

Unlike those of most herbaceous plants, the seeds of the coriander plant have a very different aroma and taste from the fresh leaves. And while the leaves, often called cilantro, are most popular in Asian and Latin American cooking, the seeds are widely used in many cuisines. There are two main types of coriander: Moroccan (kazbarah), which is more common, and Indian (dhania). The Moroccan seeds are pale tan to medium brown, spherical, and ribbed (looking something like miniature Chinese lanterns); the Indian are more oval in shape and range from a lighter tan to brown. The seeds have a warm, nutty fragrance and a sweet, somewhat pungent taste, with citrusy undertones of orange or lemon and faint notes of fresh sage; the Indian seeds are sweeter than the Moroccan. Both types have papery husks but are easy to grind, especially if they are first dry-roasted in a skillet. Coriander seeds are always toasted before grinding in India, but if they are to be used in baking and desserts, they should not be toasted. The seeds are best ground in a spice grinder, which will give a finer texture than a mortar and pestle. Ground coriander has a warm, mildly nutty fragrance and taste, again with notes of citrus.

Coriander seeds are harvested when mature, but the plants must be cut when the early-morning or late-afternoon dew is still upon them, or the seedpods will split. Then they are dried and threshed to remove the seeds.

Coriander is especially popular in Asian, Indian, African, and Mediterranean cuisines. It seasons curries, stews, and sauces, where it may also act as a thickening agent, and is added to chutneys. In India, it is used in drinks, and ground coriander is often dusted over raitas and lassis for garnish. Coriander is an essential ingredient in curry powder. It is considered an amalgamating spice, meaning it complements a wide range of other spices, and so it is used in many other spice blends as well, including ras el hanout, and in dukkah, the Egyptian spice and nut mix. In Europe and North America, coriander is more often used in baking and for pickling.

CUMIN

BOTANICAL NAME: Cuminum cyminum

OTHER NAMES: jeera, white cumin (or black cumin)

FORMS: whole seeds and ground

Another member of the parsley family, cumin is an annual plant generally considered indigenous to the Middle East, although some sources say that it originated in the Nile Valley. Cumin is a major spice, and an old one—its culinary history dates back to 5000 BC. It was used by the ancient Egyptians in mummification and is mentioned in both the Old and New Testaments. It was also thought to encourage love and fidelity. Today, it grows throughout the Middle East and North Africa, with major producers including Iran, India, Turkey, and Morocco.

Cumin is harvested when the seeds have ripened, and the whole stalks are dried. Then they are threshed to remove the seeds and the seeds are rubbed, either mechanically or by hand, to remove most of the fine “tails.”

Cumin seeds look like caraway seeds, and the two are sometimes confused—the fact that the word jeera is used to refer to both spices in India adds to the confusion, though caraway is more properly called shia jeera. (For even more on mistaken identity, see black cumin.) The small seeds are slightly curved, ridged, and pale brown to greenish-gray, and they often still have some hair-like bristles, or tails, attached. They have a pungent, warm, earthy aroma, which becomes noticeably stronger when they are lightly crushed, and an equally pungent, lingering taste with a hint of bitterness. Ground cumin is reddish-brown and has a similarly strong aroma and slightly bitter but warm taste. Toasting the seeds before grinding will make the powder more pungent; ground cumin from toasted seeds is darker than powder from untoasted seeds and has a slightly smoky taste.

Cumin is an important seasoning in Indian, Middle Eastern, Asian, North African, and Mexican and other Latin American cuisines. It is used in couscous and merguez sausages in North Africa, in kebabs in many Middle Eastern countries, and in ground meat and vegetable dishes in Turkey. It is added to curries, stews, and other regional dishes throughout India, and it is used there in breads, pickles, and chutneys. It is an essential ingredient in spice mixes such as panch phoron and garam masala, and it is mixed with ground coriander to make the simple seasoning blend known as dhana jeera. Chili powder always includes cumin, as does charmoula, the Moroccan seasoning paste.

Black cumin (Bunium persicum) is primarily grown in Kashmir, India, and it also grows in Iran and Pakistan. It is known as kala jeera in India and is sometimes called Kashmiri cumin. It is often confused with nigella, which is sometimes called black cumin but is an entirely different spice. Black cumin seeds are darker, smaller, and finer than those of regular cumin, and their fragrance is less earthy and bitter. When the seeds are fried in oil, the taste becomes nutty. Black cumin is used mostly in northern Indian cuisines and Moghul-style dishes, such as biryani and korma, as well as in breads and some spice blends and pastes. It is also a seasoning in Pakistani and Bangladeshi cooking.

CURRY LEAVES

BOTANICAL NAME: Murraya koenigii

OTHER NAMES: meetha neem, kadhi patta

FORMS: fresh and dried

The curry tree is native to southern India and Sri Lanka, and its name gives rise to confusion on several fronts. A member of the citrus family, the tree is a small tropical evergreen, but there is also a curry plant from the same region, which is used more for ornamental purposes than for cooking. And while the leaves may be used in some curries and curry blends, they are by no means an essential ingredient in curry or curry powders.

Smaller than bay leaves, curry leaves are deep green. Their herbaceous aroma is reminiscent of curry powder, with an undertone of citrus, and their flavor can be slightly bitter, especially with longer cooking. When carefully dried, the leaves maintain their green color, although their fragrance will be muted; avoid dried leaves that have darkened or turned black. Fresh leaves are optimal.

Curry leaves are commonly used in southern India and in Sri Lanka but are rarely found in the cooking of the north, although they do figure in some Gujarati dishes. They are an essential ingredient in many vegetarian dishes, including dals and lentil soups, and in curries. The leaves are often fried in oil at the beginning of cooking until very fragrant, but they can also be warmed separately in oil or ghee (clarified butter) that is then used to finish a dish. Unlike bay leaves, you can eat them whole or chopped, but younger leaves are best. Curry leaves are an ingredient in many pickles and in some chutneys. Left whole or ground with a mortar and pestle, they flavor marinades for seafood and lighter meats.

MEDICINAL USES: Curry leaves are important in Ayurvedic medicine and are prescribed for a wide variety of ills. They are believed to stimulate the appetite and to soothe indigestion.

CURRY POWDER

There are dozens, even hundreds, of curry powders found throughout India, most extensively in the southern regions, and in neighboring countries. Generic “curry powder” does not exist in Indian kitchens; instead, the spices and proportions of each blend are tailored to both the other ingredients in the dish it will season and the cook’s personal taste. Madras curry powder may be the most familiar type to Western cooks looking beyond the generic jars in the supermarket spice section, but there are many others to explore.

VINDALOO CURRY POWDER

This extremely hot curry powder usually contains coriander, cumin, turmeric, ginger, black pepper, cinnamon, nutmeg, and cloves, with a good proportion of dried chiles. Vindaloo was originally a spicy pork stew from Goa, on the southwestern coast of India, a legacy of the Portuguese explorers who landed there in the fifteenth century. They prepared a stew of pork marinated in vinegar and garlic called carne de vinha d’alhos, and as the dish acquired more of the local flavors, the name morphed into vindaloo. Vindaloo is now also made with beef, chicken, lamb, shrimp, or vegetables, although the curry powder is so hot it will overpower most vegetables.

SRI LANKAN CURRY POWDER

Sri Lankan curry blends do not typically contain dried chiles, so they are much milder than their Indian counterparts. For the most interesting version, however, the spices are roasted until very dark before grinding, which gives the mix an intense smoky aroma and flavor. These blends are much darker than other curry powders, and, in fact, they are sometimes known as black curry powder. Some powders are more lightly toasted, and the mix can also be made with untoasted spices, but the dark-roasting is what makes Sri Lankan curry powder unique. A typical blend includes coriander, cumin, cardamom, fennel, fenugreek, turmeric, and mustard seeds, along with dried pandan and/or curry leaves. This strong-tasting curry powder is especially good in beef curries, braises, and other heartier dishes.

MALAYSIAN CURRY POWDER

Curry came to Malaysia via Indian immigrants (many of whom were brought there by the British to work on spice plantations). A typical Malaysian curry blend includes coriander, cumin, fennel seeds, cinnamon, turmeric, black pepper, cardamom, cloves, and dried chiles; the heat level, of course, can vary. Malaysian curry powder is used most often for chicken or vegetable curries, many of which include coconut milk. The Penang (or Panang) curries served in Thai restaurants in the West use a similar spice blend as their base; Penang is a state on Malaysia’s northwest coast.

MADRAS CURRY POWDER

The heat levels of Madras curry powder can range from mildly spicy to very hot. A basic mix consists of coriander, cumin, dried chiles, turmeric, ginger, black pepper, cinnamon, nutmeg, cardamom, and cloves; some blends include mustard seeds and, occasionally, curry leaves. The whole spices are toasted and then ground, although many people in India today use fresh ginger separately instead of including it in the grounded blend. Madras curry powder is used in all sorts of meat, chicken, fish, and vegetable curries, as well as in other stews, soups, and rice or lentil dishes.

SINGAPORE CURRY POWDER

The cuisine of Singapore has been influenced by waves of Chinese, Indian, and Malaysian immigrants, and curry is very popular there. A typical Singapore curry powder is made with coriander, cumin, fennel seeds, fenugreek, turmeric, cloves, cardamom, and varying amounts of dried chiles; some also include rice powder. The mix can be used as a rub for grilled or roasted fish or meats, as well as in noodle dishes and all sorts of curries.

Also see Colombo.