Real Food: What to Eat and Why - Nina Planck (2016)

Chapter 6. Real Fats

SURPRISING FACTS ABOUT FATS

The Bad for You Cookbook, published in 1992, in the midst of the frenzy for “light” cooking, extolled lard, eggs, butter, and cream—for pleasure if not health. Chris Maynard and Bill Scheller presented their favorite recipes for shirred eggs, lard pie crust, and trout with bacon with unguarded enthusiasm—and this disclaimer: “As for heart attacks … we are not going to make any hard-and-fast recommendations here because we are not doctors and—far more important—we are not lawyers.”

How little has changed since then. With the first printing of this book in 2006, I hoped to liberate eaters, to release them from fear of food, especially red meat and fat. Dear Reader, I’m polling you now. Have I succeeded?

I fear not. Many Americans are still terrified of eating fats and feel guilty when they do. Monounsaturated olive oil makes the official list of “good” fats, yet few will defend saturated fats. Traditional fats are certainly more fashionable recently. The television chef and restaurateur Mario Batali made a splash putting lardo (cured fatback) on his menus, and in 2005 the food writer Corby Kummer praised lard in the op-ed pages of the New York Times. “Here’s my prediction,” wrote the trend-spotting columnist Simon Doonan in the New York Observer, after he saw Kummer’s piece on lard. “This trend is not only going to catch on, it’s going to sweep the nation.”

I still hope so. Lard may be in vogue, but hardly anyone knows that lard is good for you. In 2000, when I began to read about fats with an open mind, I learned some curious things. Consider this: lard and bone marrow are rich in monounsaturated fat, the kind that lowers LDL and leaves HDL alone. Stearic and palmitic acid, both saturated fats, have either a neutral or beneficial effect on cholesterol. Saturated coconut oil fights viruses and raises HDL. Butter is an important source of vitamins A and D and contains saturated butyric acid, which fights cancer. As for the vaunted polyunsaturated vegetable oils, we eat far too many. Refined corn, safflower, and sunflower oil lower HDL and contribute to cancer.

Back when I took the warnings about saturated fats to heart, I cooked everything—from roast chicken to salmon, mashed potatoes to polenta—with olive oil. After I did a little homework on fats, life in the kitchen got more interesting. What fun to rediscover—and in some cases learn for the first time—how to cook with traditional fats like butter and lard. Now my kitchen is stocked with local butter, lard, duck fat, and beef fat, as well as exotic oils of coconut and pumpkin seeds.

Fats have many roles in cooking. Perhaps most important, they carry and disperse flavor throughout foods. Olive oil takes up the flavor of chili, garlic, or lemon and spreads it through the dish. Chicken breast has less flavor than dark thigh meat because it contains less fat, and modern commercial pigs, bred to be lean, make for dry and flavorless pork compared with traditional breeds. The Bad for You Cookbook authors want to know: “How did the fat get bred out of hogs to the point where you’d have to render three counties in Iowa to get a pound of lard?”

Fats add and retain moisture (in roasting, for example), and they keep food from sticking in frying and baking. Bakers use solid fats like butter, lard, and coconut oil to create a flaky, crumbly texture. Perhaps most delightful, fats contribute the inimitable quality known as “mouthfeel”—think of creamy butter, silky serrano ham, or crispy skin on roast chicken. The desire for the feel of fat in food is universal. As anyone who has tried fat-free versions of real food knows, it has not been easy for food scientists to mimic the delectable feel of fat without real fat. It seems our taste for fat is innate. In 2015, researchers at Purdue University claimed that fat is the sixth essential taste. Oleogustus, as they called it, is distinguishable from the desire for the texture of fat.

Fats, in other words, are delicious. They are also necessary for health. Fats in the omega family are called essential because the body cannot make them; we must get them from foods. The brain relies on omega-3 fats; deficiency causes depression. Without fats, the body cannot absorb the fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E, and K. Fats are key to many other functions, including building cell walls, immunity, and assimilation of minerals like calcium.

Digestion is impossible without fats. The cell membrane (also made of fats) controls the muscles of the gastrointestinal tract. Fats stimulate the secretion of bile acids, which are essential for digestion. The vital role of fat in digestion is illustrated by an obscure condition called rabbit starvation, caused by a diet exclusively of lean protein. The term comes from Arctic explorers forced to live on lean winter game for months, and the symptoms are lethargy, nausea, diarrhea, weight loss, and eventually death. Without fat, digestion literally fails and you starve—even if you’re eating plenty of calories.

Granted, this form of malnutrition is not likely to threaten many Americans. Fat is cheap and ubiquitous—or at least industrial fats are. Today, overeating low-quality food is more often the cause of poor nutrition than starvation. So how much fat is healthy? I don’t count fat grams or the percentage of calories from fat and don’t recommend it. My approach is simple: I eat a variety of traditional fats and oils, and I balance rich foods with lighter ones.

However, if you would like to know how much fat people eat and how much fat experts think we should eat, here are a few numbers. Deriving less than 20 percent of calories from fat is regarded as a low-fat diet, 30 to 40 percent moderate, and 60 percent high-fat. The extreme low-fat diet is recent, hard to follow, and nutritionally dubious. In 2006, the Women’s Health Initiative trial found that low-fat diets did not prevent weight gain, heart disease, stroke, or cancer.1 The women on the “low-fat” diet were instructed to limit fat to 20 percent of calories, but that proved impossible (or perhaps merely unpalatable). These unfortunate women, who gamely ate salads without olive oil for eight years with nothing to show for it, consumed about 29 percent of their calories from fat. That’s roughly what that U.S. government recommended. The lucky women who were allowed to eat whatever they wanted (researchers call that ad libitum, a term I love) ate 37 percent fat, which happens to be typical of most human diets.

In 2014, the Annals of Internal Medicine published a study comparing a low-carbohydrate diet with ample fat with a low-fat diet rich in grains. Those who avoided carbohydrates and ate more fat, including saturated fat, lost more weight and body fat, and improved heart disease risk factors (triglycerides and HDL/LDL ratios) more than the low-fat group.

Very high-fat diets are probably inappropriate for those of us who work at desks rather than at physical labor. Most diets—actual and recommended—are 35 to 40 percent fat. The accompanying table shows the wide range of calories from fat in diets old and new.

HOW MUCH FAT IS IN THE DIET?

|

DIET |

% OF CALORIES FROM FAT |

|

Nathan Pritikin and Dean Ornish |

10 |

|

American Heart Association (AHA) |

30 |

|

U.S. Government |

30 |

|

Average U.S. diet (according to the AHA) |

33 |

|

Neanderthin (based on hunter-gatherer diets) |

35 |

|

Hunter-gatherers (according to Cordain’s studies of 229 groups) |

28-57 |

|

American cookbooks circa 1900 |

40* |

|

South Beach diet, first phase |

40 |

|

General Foods recommended diet in the 1930s |

40 |

|

Modern Greeks |

40 |

|

American lumberjacks, circa 1911 |

43 |

|

Finns |

39-50 |

|

Fulani, a Nigerian tribe |

50* |

|

Greenland Eskimos (rich in omega-3 fats from fish) |

50 |

|

Recommended diet for infants and children up to two |

50 |

|

Pacific Islanders |

57* |

|

Atkins diet, first phase |

60† |

* About 50 percent saturated fat

† About 33 percent saturated fat

IF YOU HAVE ONLY TWO MINUTES FOR FATS...

When I started to learn about the intricate chemistry of fats, it was very exciting. I studied where plant and animal fats come from and marveled at how the body makes its own fats. I wondered why the body tends to hoard polyunsaturated fats in corn oil for a rainy day, while it burns the saturated fats in butter and coconut oil quickly. Unsatisfied with the charts and tables in books, I drew my own and hung them over my desk. You can imagine my situation. I soon discovered that my friends were less fascinated with fat metabolism than I was. They asked for the essential facts on fats. Here they are.

Members of the lipid family, fats and oils (which I will call fats) consist of individual fatty acids, which may be saturated, monounsaturated, or polyunsaturated—terms describing their chemical structure. All fatty acids are strings of carbon atoms encircled by hydrogen atoms. When every carbon atom bonds with a hydrogen atom, the fatty acid is saturated. If one pair of carbon atoms forms a bond, the fatty acid is monounsaturated. If two or more pairs of carbon atoms form a bond, the fatty acid is polyunsaturated. A carbon-hydrogen bond is known as a saturated or single bond. A carbon-carbon bond is called an unsaturated or double bond.

THE CHEMISTRY OF FATS

All fats consist of individual fatty acids made of hydrogen and carbon. Fatty acids may be saturated, monounsaturated, or polyunsaturated.

SATURATED

All carbon atoms form saturated bonds with hydrogen

Example: stearic acid (beef and chocolate)

MONOUNSATURATED

Two carbon atoms create one unsaturated bond

Example: oleic acid (olive oil and lard)

POLYUNSATURATED

More than one pair of carbon atoms create two or more unsaturated bonds

Example: linoleic acid (corn oil)

All the fats we eat are a blend of saturated, monounsaturated, and polyunsaturated fatty acids. Fats are identified by the predominant fatty acid. Beef is mostly saturated, so we call it a saturated fat—even though it contains monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids, too. Butter is mostly saturated, olive oil mostly monounsaturated, and corn oil mostly polyunsaturated. Lard is difficult to characterize because it varies with the diet of the pig, but it’s about 50 percent monounsaturated, 40 percent saturated, and 10 percent polyunsaturated. Because it is 60 percent monounsaturated and polyunsaturated, lard is correctly grouped with unsaturated fats.

An important quality of every fatty acid is its ability to withstand heat. The more saturated the fat, the more sturdy it is, because saturated bonds are stronger than unsaturated bonds. Delicate unsaturated bonds are easily damaged or oxidized by heat. When you heat a fat to the smoking point, the fatty acids are damaged. Unsaturated fats also spoil more quickly than saturated fats. Spoiled fats are called rancid.

Oxidized fats contribute to cancer and heart disease. According to Science, “Unsaturated fatty acids … are easily oxidized, particularly during cooking. The lipid peroxidation chain reaction (rancidity) yields a variety of mutagens … and carcinogens.”2 At the University of Minnesota, researchers found that repeatedly heating vegetable oils, including soybean, safflower, and corn oil to frying temperature can create a toxic compound, HNE, linked to atherosclerosis, stroke, Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, and liver disease.3 “We are, it seems, biologically primed not to eat oxidated fat,” writes Margaret Visser in Much Depends on Dinner, “for doing so can cause diarrhea, poor growth, loss of hair, skin lesions, anorexia, emaciation, and intestinal hemorrhages.” That’s why it was bad news for health when fast-food restaurants stopped using saturated beef fat and palm oil, and started frying foods in rancid polyunsaturated oils.

In the kitchen, some fats are appropriate for heating, others acceptable, and some unsuitable. Heavily saturated fats (which tend to be solid at room temperature) are best for heating, monounsaturated fats are second best, and polyunsaturated fats (liquid at room temperature) are ideally used cold. Fortunately, there is a traditional fat for every culinary need. For roasting and sautéing, use butter, coconut oil, or lard, which are mostly saturated and monounsaturated. Chiefly monounsaturated oils, such as olive and macadamia nut, are the next best choice for cooking. A good blend for sautéing is half butter, half olive oil. Peanut and sesame oil, which contain more polyunsaturated fats, are less suitable for cooking but acceptable. In vinaigrettes and other cold dressings, use olive or nut oils.

THE BEST COOKING FATS

Traditional cooking fats are saturated and thus heat-stable.

|

SATURATED |

MONOUNSATURATED |

POLYUNSATURATED |

|

HEAT-STABLE |

MODERATELY STABLE |

UNSTABLE |

|

IDEAL FOR COOKING |

ACCEPTABLE FOR MODERATE HEAT |

IDEALLY USED COLD |

|

Beef |

Canola oil |

Fish oil |

|

Butter |

Lard |

Flaxseed oil |

|

Coconut oil |

Macadamia nut oil |

Walnut oil |

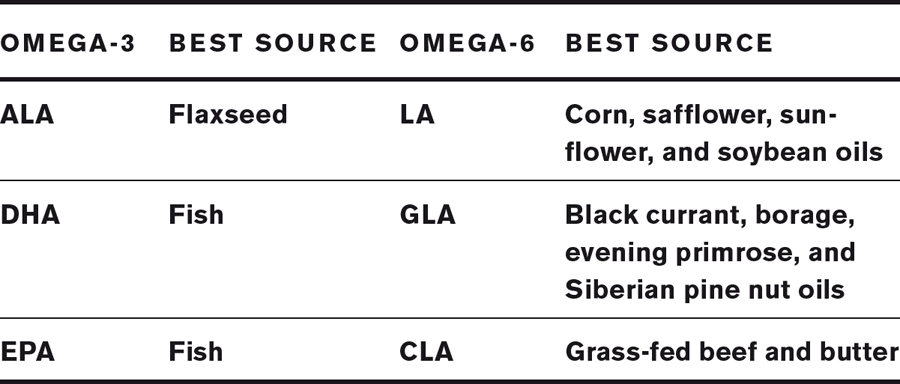

The body can manufacture some fats, while others, called essential, must be found in foods. The essential fats are polyunsaturated omega-3 (best found in fish) and omega-6 (grain and seed oils). They have equally important but opposite effects on the body. According to a 2015 study published in Nutrition Journal, the ideal diet contains roughly one to four times more omega-6 than fats, but the typical American eats eleven to thirty times more omega-6 than omega-3 fats. Too few omega-3 and too many omega-6 fats leads to inflammation, obesity, diabetes, heart disease, cancer, and depression.

Omega-3 fats include alpha-linolenic acid (ALA), docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA). Flaxseed oil, grass-fed beef and butter, and pastured eggs all contain some omega-3 fats, but the best source is fish. The main omega-6 fat is linoleic acid (LA), found in grain and seed oils such as corn, safflower, and soybean oil. Once rare in the diet, the omega-6-rich oils are now ubiquitous, especially in junk food, and we eat too many.

Gamma-linolenic acid (GLA) and conjugated linoleic acid (CLA) are omega-6 fats which tend to behave like omega-3 fats in the body. In theory, the body can make GLA from the LA in corn, but the conversion is inhibited by many factors. Direct food sources of GLA are the oils of borage, black currant seed, evening primrose, and Siberian pine nuts. GLA can address premenstrual problems, reduce inflammation, dilate blood vessels, reduce clotting, and aid fat metabolism. CLA, which fights cancer and builds lean muscle, is found almost exclusively in grass-fed beef and grass-fed butter.

Each fat has different nutritional qualities thanks to its particular fatty acids. For example, butter contains saturated lauric acid, which fights viruses. Lard and olive oil contain monounsaturated oleic acid, which lowers LDL. Any fatty acid (such as oleic acid) is chemically identical whether it’s from lard or olive oil, and has the same effect in the body.

THE ESSENTIAL FATS

The essential fats must be eaten in the right quantities. The industrial diet contains too much la from vegetable oils, which leads to inflammation, obesity, diabetes, and heart disease.

With animal fats, the breed and especially the animal’s diet affect fatty acid composition and nutritional value. In other words, all beef fat is not identical. Grass-fed beef contains more polyunsaturated omega-3 fat and more CLA than grain-fed beef. Grass-fed cream contains more beta-carotene, vitamin A, and CLA than cream from grain-fed cows. Lard from pigs that eat coconut contains more saturated lauric acid than lard from pigs that eat acorns.

The nutritional value of vegetable oils, on the other hand, is affected by how the oil was processed. Refined vegetable oils such as corn and soybean oil are pressed under high heat. Vitamin E is destroyed, and delicate polyunsaturated fats are oxidized. In extra-virgin olive oil, the antioxidants and vitamin E remain intact. Polyunsaturated oils, such as walnut and flaxseed, should be cold-pressed.

This is the most important thing about the nutrition of fats. All the traditional fats—ideally unrefined—are healthy in moderation. The body needs all three kinds of fats (saturated, monounsaturated, and polyunsaturated) for various purposes, from pregnancy to digestion to thinking.

Aren’t some fats unhealthy? Yes. It’s easy to remember the bad ones: they are the industrial fats recently added to our diet. The unhealthy fats are refined vegetable oils, including corn, safflower, sunflower, and soybean oil, and synthetic trans fats. Trans fats are formed by hydrogenation, in which unsaturated oils are pelted with hydrogen atoms to make an artificially saturated fat. That’s how they make firm margarine from liquid corn oil. Like natural saturated fat, hydrogenated oils are solid at room temperature and shelf-stable, which makes them useful for processed foods and baked goods. But trans fats lower HDL and cause heart disease, among other maladies. Industrial vegetable oils are unhealthy because they are too rich in omega-6 fats and because they are typically refined with heat, which makes them rancid and carcinogenic.

I’ve done my best for brevity and greatly simplified the complex chemistry of fats. But the moral of the story is simple. If you’re trying to remember which fats are healthy, follow this rule: eat the foods we’ve eaten for thousands of years in their natural form. If you can’t find the perfect version of a food—say, 100 percent grass-fed beef—look for the next best thing. Any version of the traditional fats will be better for you than any version of the industrial fats. Those you must avoid like the proverbial Black Death.

HOW I STOPPED WORRYING ABOUT SATURATED FATS

At Bonnie Slotnick’s, a wonderful East Village bookshop, I was hunting for clues to the traditional American diet as if they were pottery shards, when Bonnie showed me Twenty Lessons in Domestic Science, a slim book billed as a “condensed home study course.” It sold for two dollars in 1916, but I was happy to pay fourteen dollars. Twenty Lessons presents the food groups, nutritional information, recipes, and “Hints for the Housewife.” “Make a business of your kitchen,” it says, “and run that business as carefully as does the merchant who sells you your food.” Very sensible.

TRADITIONAL AND INDUSTRIAL FATS

THE BASICS

✵All the traditional fats are healthy

✵The industrial diet contains too many omega-6 fats and too few omega-3 fats. This leads to obesity, diabetes, heart disease, cancer, and depression

✵Trans fats lower HDL and cause heart disease

✵With animal fats, the animal’s diet matters for our health

✵With vegetable oils, processing matters for our health

TRADITIONAL HEALTHY FATS: EAT UP

ANIMAL FATS

✵Fat from grass-fed cattle, sheep, bison, and other game

✵Butter and cream from grass-fed cows

✵Lard from pastured pigs fed a natural diet (pigs eat anything, so their diet varies)

✵Egg yolks from pastured chickens, ducks, and geese

✵Fish oils (preferably wild), especially cod-liver oil

VEGETABLE OILS

✵Cold-pressed, extra-virgin olive oil

✵Cold-pressed, unrefined flaxseed oil

✵Wet-milled, unrefined coconut oil

✵Cold-pressed, unrefined macadamia nut oil

✵Cold-pressed, unrefined walnut oil

✵Cold-pressed, unrefined sesame oil

MODERN INDUSTRIAL FATS: AVOID

✵All hydrogenated and partially hydrogenated oils, including lard and all vegetable oils

✵Corn, safflower, sunflower, and soybean oils, especially when refined or heated

All-but-forgotten frugality is not what I find curious about old nutritional primers. They illustrate just how dramatically the American diet has changed and how fast. In Lesson No. 1: The Composition of Food Materials, a government “Expert in Charge of Nutritional Investigations” at the U.S. Department of Agriculture provides nutritional information on meat, dairy, fish, grains, and other foods. It was the sketch of fats and oils that stood out; only five were mentioned: bacon, lard, beef suet, butter, and olive oil. In 1916, these were the fats we ate. Not anymore.

A child of my times, I once steered clear of saturated fats. Most people, and most doctors, would have regarded my diet and habits as stellar. In those days, I ate a lot of fish, vegetables, and olive oil; I was a runner and got plenty of sleep. But my digestion was poor, my skin, hair, and nails were dry and brittle, and I was often laid low by colds and the flu. Today my complaints are gone, I rarely get sick, and I feel great. The main change is eating saturated fats (chiefly from beef, butter, and coconut oil) every day.

Perhaps you’re like me a ten years ago, and you’ve never heard a good word about “artery-clogging” saturated fats. Actually, they are vital to health. The most basic function of saturated fats is structural: they make up half of cell membranes. The site of all chemical activity in the body, the cell is a barrier to unwanted substances and a gateway to good ones, and the cell membrane is an extremely fine tool. A human hair is eighty thousand nanometers wide. (One million nanometers make a millimeter.) By comparison, the cell wall is tiny: only ten nanometers thick. It needs exactly the right degree of flexibility and permeability: neither too stiff nor too floppy, neither impenetrable nor too porous. Saturated fats provide stiffness and a barrier, unsaturated fats flexibility and porosity.

Certain saturated fats (short- and medium-chain fatty acids) are easy to digest because they do not have to be emulsified first by bile acids, as long-chain polyunsaturated fats do. These saturated fats (in butter and coconut oil) are used directly for energy, rather than stored as fat. Saturated lauric acid in coconut oil actually increases metabolism.

Saturated fats are required for the absorption of calcium and other minerals. When the diet contains saturated fats, the body is better able to retain the vital long-chain polyunsaturated fats, such as the omega-3 fats in fish.4Saturated fats also build immunity by fighting harmful microbes, viruses, and other pathogens, especially in the digestive tract. Saturated lauric acid destroys the HIV virus.

Saturated fats may fight infections, but what about heart disease? Here again, I found surprises. Saturated fats lower blood levels of lipoprotein (a), which leads to clotting and atherosclerosis. Even the fats around the heart muscle are saturated.5 They include stearic acid, found in beef and chocolate, and palmitic acid, in coconut oil, palm oil, and butter.6 What about the “fatty” plaques in arteries that can burst and cause heart attacks? Fat is only one part, often a small one, of such plaques.7 Moreover, only 26 percent of the fat in arterial plaques is saturated.8 The rest is unsaturated, of which more than half is polyunsaturated.

The cholesterol theory says that eating saturated fats raises blood cholesterol in unhealthy ways. The truth is more complicated. First, about half of blood cholesterol has nothing to do with diet. Second, when you eat too much saturated fat, the body converts it to monounsaturated fat, which lowers LDL and leaves HDL alone.9

Furthermore, certain saturated fats (palmitic and stearic acid) have a neutral or beneficial effect on cholesterol. Forgive me for mentioning stearic acid again; perhaps I’ve grown partial to it because I’m fond of chocolate, but it kept turning up in my reading. Stearic acid makes a curious case study in the history of fats.

Ancel Keys, an early proponent of the cholesterol theory, made the Mediterranean diet, featuring fish, vegetables, olive oil, and red wine, famous in the 1950s and ’60s. Keys developed predictive equations on diet and cholesterol. Most of his calculations, which were influential, showed that saturated fat raised cholesterol more than polyunsaturated fat, as he expected. Keys also found that stearic acid did not raise cholesterol, a detail he ignored. Later, other research confirmed the neutral or positive effect of stearic acid on blood cholesterol, especially the ratio of HDL to LDL. The National Research Council’s report Diet and Health and the surgeon general’s Report on Nutrition and Health both noted that stearic acid did not raise cholesterol. In 2005, the journal Lipids wrote: “Stearic acid lowers LDL cholesterol.”10

Once the facts were in on stearic acid, did the experts tell us that the saturated fats in beef and chocolate were good for the heart? No. According to the International Food Information Council, “In light of the findings about stearic acid, some researchers recommend no longer grouping it with other saturated fats.”11 In other words, they proposed to redefine saturated fats rather than admit that some saturated fats don’t raise cholesterol.

Diabetes is a risk factor for heart disease, and for some time, diabetics were prescribed a low-fat, high-carbohydrate diet of fruit, bread, pasta, and nonfat dairy foods. Now (sensibly) there is more emphasis on protein, but saturated fats are still taboo. The American Diabetes Association says that monounsaturated fats are best; omega-6 fats and saturated fats are to be avoided.

Dr. Diana Schwarzbein, whose specialty is endocrine and metabolic diseases, disagrees. She found that type 2 diabetics got worse on a low-fat, high-carbohydrate diet. Faithful to her dietary prescriptions, her patients gained weight, their cholesterol rose, and they required more insulin, not less. Frustrated, Schwarzbein decided to experiment. When she added a little fat and protein to the menu, results were excellent. Her patients lost weight and had more energy. Their blood sugar and cholesterol fell. To her surprise, the best results were in the patients who “cheated”—they ate saturated fats and cholesterol in “real mayonnaise, real cheese, real eggs, and steak every day,” she writes. In The Schwarzbein Principle, she writes, “My clinical experience with thousands of people has shown that eating saturated fats is not the culprit! On the contrary … patients who have increased consumption of saturated fats (as well as all other good fats) have improved their cholesterol profiles, decreased blood pressure, and lost body fat, thereby reducing their risk of heart disease.”

My own (admittedly unscientific) experience has helped convince me that saturated fats don’t cause unhealthy cholesterol. As I learned more, I conducted a tiny, unintentional experiment. Gradually, I ate more saturated fat in foods like cream, chocolate, and coconut, until I was eating plenty every day—as I still do. After eating this way for several years, my cholesterol, HDL, LDL, triglycerides, and other signs of cardiovascular health are off-the-charts healthy by the standards of the National Cholesterol Education Program. Indeed, the more saturated fat I eat, the better the numbers look.

The story is—of course—not so simple. I also do other things the experts call heart-healthy: I exercise, I don’t smoke, and I eat more than my share of fruit, vegetables, olive oil, fish, dark chocolate, and walnuts. I don’t eat trans fats or refined vegetable oils, and I steer clear of sugar and white flour.

Mine is a balanced diet, to be sure, and the reader (or cardiologist) who favors moderation in all things might consider moderation its chief virtue. Perhaps. But I routinely eat more saturated fat than experts advise. They would not recommend my daily fare: two eggs with butter for breakfast, coconut curry for lunch, cream in my cocoa, and well-marbled rib eyes. The medical literature has a label for people like me: exceptions to the rule. If saturated fats raise cholesterol, and I eat saturated fats but my cholesterol is fine, I am a “nonresponder.” Or it could be that the rule is flawed.

Advice on fats is evolving slowly. In 2004, the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition published a striking article. The authors called our understanding of saturated fats in particular “fragmented and biased” because research on fats had been so limited. “The approach of many mainstream investigators … has been narrowly focused to produce and evaluate evidence in support of the hypothesis that dietary saturated fat elevates LDL,” the authors wrote. “The evidence is not strong.”12 They noted that saturated fats were “disappearing” from the food supply and asked, “Should the steps to decrease saturated fats to as low as agriculturally possible not wait until evidence clearly indicates which amounts and types of saturated fats are optimal?”13

In 2005, along came a study of twenty-eight thousand middle-aged men and women in Malmo, Sweden.14 Researchers looked for links between fats and mortality from heart disease and from all causes. “No deteriorating effects of high saturated fat intake were observed for either sex for any cause of death,” they wrote. “Current dietary guidelines concerning fat intake are thus not supported by our observational results.”

Recent research vindicates saturated fats. In 2014, Dr. Rajiv Chowdhury and colleagues published a paper in the Annals of Internal Medicine. After reviewing nearly 80 studies—a method called meta-analysis—they found no link between saturated fats and heart disease. When the researchers looked at specific fatty acids in the blood, they found, counter to conventional thinking, that margaric acid, a saturated fat found in butter, was associated with less cardiovascular risk. The omega-3 fats found in fish were also beneficial. Two types of fats—human-made trans fats and omega-6 fats, typically from grain and seed oils—were associated with more heart disease. “It’s not saturated fat that we should worry about,” said Chowdhury, a cardiovascular epidemiologist at Cambridge University. “It’s the high-carbohydrate or sugary diet that should be the focus of dietary guidelines.”

How much evidence do you need? That’s up to you. But if you still fear that traditional saturated fats are trouble, my hunch is that more evidence in favor of butter will soon come your way.

PLEASE BUTTER YOUR CARROTS

In fashion terms, fats are like a string of pearls—they go with everything. The modern habit of eating chicken breasts and other lean cuts trimmed of all offending fat is new, an aberration in three million years of human history. Most people never ate protein without fat for the simple reason that in nature, protein and fat go together. In animals, fat and muscle are attached.

Eating the fat along with the protein is also frugal and efficient. Traditionally, hunters and farmers ate the whole animal, including the skin, extra fatty bits, bone marrow, brain, and rich organ meats. Contemporary human hunters, like carnivores, go for the organs and fatty parts first. Moreover, when times are good—that is, when there is plenty of food—hunters may even leave the muscle behind for scavengers. Vitamins and other nutrients in the fats and organs are simply more valuable than the lean protein.

Above all, eating protein with fat makes nutritional sense, because all food, and protein in particular, requires fat for proper digestion. As we saw earlier with “rabbit starvation,” without fat in the diet, digestion fails and you starve, but not for lack of calories.

What is true of meat is true of all fat-and-protein pairs: they go together. Consider, for example, two near-perfect foods: eggs and milk. Both foods are a complete nutritional package, designed for a growing organism’s exclusive nutrition, and must contain everything the body needs to assimilate the nutrients they contain. Thus the fats in the egg yolk aid digestion of the protein in the white, and lecithin in the yolk aids metabolism of its cholesterol. The butterfat in milk facilitates protein digestion, and saturated fat in particular is required to absorb the calcium. Calcium, in turn, requires vitamins A and D to be properly assimilated, and they are found only in the butterfat. Finally, vitamin A is required for production of bile salts that enable the body to digest protein. Without the butterfat, then, you don’t get the best of the protein, fat-soluble vitamins, or calcium from milk. That’s why I don’t eat, and cannot recommend, egg white omelets and skim milk. They are low-quality, incomplete foods.

FATS GO WITH EVERYTHING

In each classic pair, fats help the body assimilate, use, or convert essential nutrients.

FAT AND PROTEIN

Roast chicken (with the skin)

Eggs (with the yolks)

FAT AND VITAMINS

Vitamins A, D, E, and K are fat-soluble; eat them with fat

FAT AND BETA-CAROTENE

Buttered carrots

Collards with fatback

Spinach salad with bacon

Flank steak with arugula

Beef with broccoli

SATURATED FAT AND OMEGA-3 FATS

Fish with butter or cream sauce

SATURATED FAT AND CALCIUM

Whole milk

Yogurt, cheese, and sour cream made from whole milk

Without fats, even vegetables are less nutritious. Brightly colored vegetables are rich in antioxidant carotenoids. They go better with butter. In 2004, Iowa State University researchers who compared people eating salads with traditional or fat-free dressings found those shunning fat failed to absorb lycopene and beta-carotene, powerful antioxidants that boost immunity and fight cancer and heart disease. “Fat is necessary for the carotenoids to reach the absorptive intestinal walls,” said the lead researcher, Wendy White. Lycopene is found in tomatoes and beta-carotene in orange, yellow, and green vegetables.

For vegans, who must rely entirely on vegetables for vitamin A, dressing salad with a traditional fat is even more critical. Recall that true vitamin A is found only in animal foods (especially butter, eggs, fish, and liver). The body can make its own vitamin A from the beta-carotene in carrots, but the conversion is costly (it requires fats and bile salts made from cholesterol) and uncertain. Babies, children, diabetics, and those with thyroid disorders make vitamin A with difficulty. Thus a person eating a strict vegan diet risks vitamin A deficiency. As Hindus and other traditional vegetarian groups know, butter and eggs are vital ingredients in vegetarian cooking.

Last but not least, the chemistry of fats can explain the long tradition of serving fish with butter and cream. Saturated fats are required to assimilate omega-3 fats, and they make omega-3 fats go farther in the body. That’s the solid nutritional logic behind the delicious combinations of lobster with melted butter and Dover sole with butter sauce.

MAKE MINE EXTRA-VIRGIN

In 1971, an Italian internist in her seventies named Mary Catalano was the only doctor in Buffalo who would deliver babies at home. At my mother’s final prenatal checkup, Dr. Catalano, who specialized in heart disease, had an unusual question: was there olive oil at the house? The answer was yes. So, right after I was born, the doctor gently wiped my skin with olive oil. Now I wish we could ask her why. Olive oil is often used in homemade cosmetics, but I wonder if my rubdown was part of some long-lost midwifery tradition.

The queen of vegetable oils, olive oil is the most famous fat in the world, with a long, glorious history in cosmetics and cuisine. Olive oil is one of the first foods Italian babies eat, and one of the last foods offered to the dying. The evergreen olive tree grows all over the world, from Tunisia to California to Australia, and can still bear fruit at the grand age of one thousand years. Olive oil is a staple food in Greece, Italy, Portugal, and Spain, where most of the world’s olive oil is produced. Its flavor is complex and varied—sometimes grassy and peppery, sometimes buttery and smooth.

Olive oil is also good for you. It is rich in vitamin E and other powerful antioxidants called polyphenols; both nutrients prevent heart disease and cancer. By preventing oxidation, they also keep the oil itself fresh. Olive oil inhibits platelet stickiness, lowers blood pressure, and reduces inflammation. Olive oil has a good reputation with cardiologists because it is 70 percent monounsaturated oleic acid, which lowers LDL.

They probably don’t know that olive oil contains about 8 to 20 percent saturated palmitic acid (also found in palm oil, butter, and beef), which has a neutral or beneficial effect on cholesterol.15 Palmitic acid lowers LDL.16Olive oil also contains about 10 percent LA, the essential omega-6 fat. Recall that the industrial diet contains too much LA from vegetable oils. If you eat corn, safflower, or soybean oil, replace them with olive oil, and you will have plenty of LA.

OLEIC ACID IN OLIVE OIL AND ANIMAL FATS

|

FOOD |

% OF OLEIC ACID |

|

Olive oil |

71 |

|

Egg |

50 |

|

Beef fat |

48 |

|

Lard |

44 |

|

Chicken fat |

36 |

|

Butter |

29 |

Healthy, delicious, and versatile in the kitchen, olive oil has never fallen out of culinary favor. It is often used cold in vinaigrettes, pesto, and other raw sauces, which protects its delicate vitamins and antioxidants, but it is also suitable for cooking at moderate temperatures because it’s about 85 percent monounsaturated and saturated. Many “heart-healthy” recipes call for polyunsaturated vegetable oils such as corn or grapeseed oil for sautéeing, but olive oil is a better choice. According to Lancet Oncology, “The high content of the monounsaturated fat, oleic acid, is important because it is far less susceptible to oxidation than the polyunsaturated fat, linoleic acid, which predominates in sunflower oil” and other grain and seed oils.17 A blend of butter and olive oil is even more heat stable because of the butter’s saturated fats.

Unlike other vegetable oils, olive oil requires little processing—and for nutrition and flavor, the less the better.18 Olive oil comes in three grades: plain, virgin, and extra-virgin. Virgin and extra-virgin oils are made in the traditional way with minimal damage to the fruits, which are simply crushed between stones without heat or chemicals. Though labor-intensive, handpicking and cold-pressing preserve delicate vitamin E and antioxidant polyphenols. According to the definition of the International Olive Oil Council, extra-virgin oil comes from the first pressing of the fruit, has no defects in taste or smell, and has acidity of 1 percent or less. Many producers have even higher standards for acidity. When olives are handpicked and cold-pressed the same day, for example, acidity is lower. The best olive oil is unfiltered to retain all its nutrients and flavor (it will be cloudy) and bottled in dark glass to shield it from oxidizing light.

Most commercial olive oil is the lowest grade—plain. It is usually labeled olive oil, or sometimes, confusingly, pure or 100 percent pure olive oil. For this grade, the olives are picked by machine, which tends to bruise them. Bruised olives ferment and oxidize, which raises acidity and produces inferior oil.19 The olives are pressed repeatedly with heat and subjected to chemical extraction, which diminishes nutrients and flavor. The base of plain olive oil is “lampante oil,” so-called because it was once burned in lamps. Almost inedible in its crude state, it is either rancid or too acidic and must be refined to make it fit to eat. Treatments include acid washing, degumming, bleaching, and deodorization to remove foul odors.20 The refined lampante oil is blended with virgin oil to make plain olive oil palatable.

The more olive oil is refined, the less vitamin E and antioxidants it has, and you can measure the difference: extra-virgin oil has significantly more polyphenols than lesser grades.21 More polyphenols means better flavor and more health benefits. “High consumption of extra virgin olive oils, which are particularly rich in these phenolic antioxidants … should afford considerable protection against cancer (colon, breast, skin), coronary heart disease, and ageing by inhibiting oxidative stress,” say antioxidant experts.22 Consumption of olive oil (and fruits and vegetables) significantly reduces the risk of breast cancer, while consuming margarine increases it.23

How, exactly, does olive oil fight heart disease and cancer? Oxidized LDL is a cause of heart disease. Polyphenols inhibit oxidation of LDL, and the more the better.24 Polyphenols may also stimulate antioxidant enzymes and increase HDL. Another antioxidant in extra-virgin oil, squalene, fights skin cancer. Still other antioxidants called lignans inhibit cell growth in cancers of the skin, breast, colon, and lung.

To reap all the flavor and health benefits of olive oil, buy the best oil you can afford, ideally extra-virgin, cold-pressed, and organic. I use extra-virgin oil, even for cooking. When you heat extra-virgin oil, antioxidants counter the damage to the delicate vitamin E and unsaturated fats. If that’s too expensive, use virgin oil for frying and extra-virgin for cold dressings. Beware of “light” olive oil. It’s a marketing gimmick to make you think it has fewer calories. Refined to remove color and scent, it lacks the flavor and antioxidants of extra-virgin oil. Store olive oil away from heat and light.

Most olive oils, including better-quality brands, are blends of different crops, to ensure consistent flavor and quality, not unlike wine blended from different grape harvests. The very best olive oils, again like wines, are estate bottled, which typically means the olives from one harvest were pressed and bottled where they were grown. Fancy estate oils are often seasonal and usually quite delicious. But for me, at least, they’re a rare treat. I use a lot of olive oil, so I watch my budget.

MY OPINION OF THE MINOR VEGETABLE OILS

What oil is best for sautéing? When I talk with people about fats, this is one of the most common questions. The short answer: not polyunsaturated vegetable oils such as corn, safflower, sunflower, and soybean oil. Those fats are too delicate. When heated, they oxidize and become rancid and carcinogenic. The best cooking fats are mostly saturated, such as butter, beef, and coconut oil. Second best are the mostly monounsaturated fats, such as lard, macadamia nut oil, and olive oil.

These answers, unfortunately, don’t satisfy most people. They might regard olive oil as too expensive for everyday cooking. Often they’re looking for a “neutral” flavor. The bland taste of lard makes it a great platform for flavors sweet and savory—one reason it’s perfect for pie crust. However, it seems that many people are not ready to start frying chicken in lard, even though good cooks all over the world do just that. Olive oil, butter, and coconut oil do have pronounced flavors. I love the scent, flavor, and feel of coconut oil, but usually I save it for certain dishes like fish curry. Coconut oil does not flatter asparagus or new potatoes.

The goal of a “neutral” flavor is tricky anyway—perhaps even futile. Fats, more than any other food, are aromatic. They not only have flavor but also carry flavors on the palate. Having tasted many fats, I’ve concluded there is no such thing as a flavorless fat. Butter tastes like cream, olive oil like olives, corn oil like corn. That’s why many oils (including avocado, olive, corn, and coconut) are refined, bleached, or deodorized—to strip them of scent and flavor. The result is a bland fat, to be sure, but with unhappy results, in every case, for the nutrients in the natural version.

It may be best to forget the quest for a “neutral” flavor. Fats are assertive; for that reason they lend character to whole cuisines. Middle Eastern dishes call for frying many foods in lamb fat. Most Americans would call that a very strong flavor; lamb colors all the dishes, in the same way olive oil leaves its mark on the cuisine of Greece, where even desserts are made with the herbaceous oil. We may regard olive oil as somehow more neutral tasting than lamb fat, so redolent of lanolin, but that’s merely a matter of taste and familiarity.

My advice is to treat fats as you would any other ingredient: choose the feel and the flavor to match the dish. As I’ve mentioned, I mostly use butter and olive oil, or a combination, for sautéing and roasting. For certain dishes, like roasted red peppers, I use only olive oil, and I simply don’t worry about the few polyunsaturated fats it contains. But it is true that heating any unsaturated oil is less than ideal. Sometimes I blanch or steam vegetables and add the olive oil after cooking, which has the added virtue of showcasing the flavor of relatively expensive extra-virgin oil.

A FEW OTHER VEGETABLE OILS

ACCEPTABLE FOR COOKING

✵Macadamia nut oil is about 85 percent monounsaturated, which makes it suitable for cooking, though I prefer it cold. Buttery and nutty, it has a lovely flavor, but it’s not cheap.

✵Peanut oil is 46 percent monounsaturated oleic acid, 31 percent polyunsaturated LA, and about 17 percent saturated. Because it’s about 60 percent monounsaturated and saturated, it’s fine for cooking, if the flavor suits you. Don’t buy hydrogenated oil.

✵Sesame oil is 43 percent polyunsaturated LA, 41 percent monounsaturated, and 15 percent saturated. It’s suitable for cooking, but the flavor is hardly neutral, especially toasted oil. Its unique antioxidants, including sesamin, are not destroyed by heat like most antioxidants; they protect the polyunsaturated fats. In Chinese cooking, sesame oil is typically used cold in salads or added after cooking.

BEST USED COLD

✵Flaxseed oil comes from linseed. Ground flaxseed has been a traditional food and medicine in the Mediterranean region and Africa for thousands of years. It’s the best plant source of omega-3 ALA (60 percent), which the body uses to make DHA and EPA. Flaxseed oil has a distinctive herbaceous, woody flavor. A blend of flaxseed and olive oil in vinaigrette is a good way to slip omega-3 fats to vegetarians and people who don’t eat enough fish. ALA is very sensitive to light and heat. Keep flaxseed oil in the fridge.

✵Grapeseed oil is about 70 percent polyunsaturated LA and rich in heat-sensitive vitamin E, which makes it a poor frying fat. I don’t use it, mostly because it’s so rich in omega-6 fats, but people like it for its neutral flavor.

✵Walnut oil is about 54 percent polyunsaturated LA. It also contains about 12 percent omega-3 ALA. Highly unsaturated, walnut oil should be cold-pressed, kept cold, and used cold. It has a pronounced, tannic flavor I happen to love, and I use it often in salad dressing, sometimes with roasted walnuts.

Even after I confess to heating olive oil and reveal my (unoriginal) olive-oil-and-butter blend secret, people still want to know about neutral vegetable oils for sautéing, frying, and dressing salads. There are many culinary vegetable and nut oils, from Brazil nut to grapeseed to pecan; you will have to find your favorites. See the sidebar for a few vegetable oils I might use—or wouldn’t disapprove of, anyway—other than olive and coconut oil.

What about the common vegetable oils grown in the American heartland, including corn, safflower, sunflower, and soybean oil? I don’t use, or recommend, any of the modern grain and seed oils. They’re rich in polyunsaturated omega-6 LA (too delicate for heat), and most Americans eat far too many omega-6 fats already. They also lower HDL.

Other vegetable oils mentioned here—sesame, peanut, and grapeseed—are also fairly rich in omega-6 LA. That’s one reason I seldom use them, but I also prefer other oils. If you don’t eat corn, safflower, sunflower, or soybean oil, a little sesame or peanut oil, if that’s what you prefer for a beef and broccoli stir-fry, won’t do any harm.

COCONUT OIL IS GOOD FOR YOU

In the nineteenth century, coconut oil was common in baked goods, from cookies to crackers. A saturated fat like coconut oil is ideal for baking because it’s stable when heated, remains solid at room temperature, and has a long shelf life. Cookie companies and home bakers alike used it. An 1896 ad for “pure and wholesome cocoanut butter” recommended it in place of lard and butter and boasted endorsements from chefs and doctors.

By the middle of the twentieth century, coconut had all but disappeared from the American diet. What happened? There was a commercial battle over what fat would be used in baked goods, and the competitors were domestic vegetable oils and imported tropical oils, including palm and coconut oil. As the two industries fought for market share, nutrition experts threw the knockout punch: the idea that saturated fats cause heart disease. Coconut oil imports never recovered.

In a short time, most commercial baked goods were made with another solid and shelf-stable fat: hydrogenated vegetable oil. That turned out badly; now we know that trans fats cause heart disease. Meanwhile, coconut oil turns out to be innocent of the cholesterol charges, with other virtues in the bargain.

The coconut palm tree grows in the tropics and subtropics, including Asia, India, Africa, and Latin America, where the milk, flesh, and oil of the coconut fruit are used in a variety of dishes, from drinks to soups and sauces. Coconut flesh contains fiber, fat, vitamins B, C, and E, and calcium, magnesium, iron, zinc, and potassium. Coconut oil is a folk remedy in many cultures, from the Philippines to Sri Lanka. Polynesians, who eat coconut and coconut oil every day, call it the “Tree of Life.”

Like all saturated fats, coconut oil is solid at room temperature; it turns soft at about seventy-six degrees Fahrenheit. The oil is rich (64 percent) in medium-chain saturated fatty acids, which have unusual properties. The main fat (49 percent) is lauric acid, an antimicrobial, antifungal, and antiviral fatty acid all but unique to coconut oil and breast milk. Lauric acid kills fat-coated viruses, including HIV, measles, herpes, influenza, leukemia, hepatitis C, Epstein-Barr, and bacteria, such as Listeria, Helicobacter pylori, and strep.25 Monolaurin, an agent the body makes from lauric acid, fights the herpes and cytomegalovirus viruses.26

The medium-chain fats in coconut oil don’t need to be emulsified by bile acids before they are digested, as long-chain polyunsaturated fats do. Thus the body burns coconut oil more quickly than long-chain polyunsaturated fats like soybean oil, which it tends to store for later. For this reason, lauric acid is easy to digest, and for decades doctors have fed coconut oil to patients unable to digest polyunsaturated fats.27 A number of studies in both animals and people show that coconut oil, when compared with polyunsaturated fats, enhances weight loss.28

What about heart disease? In the 1960s, Dr. Ian Prior, director of epidemiology at Wellington Hospital in New Zealand, studied all twenty-five hundred people on the South Pacific islands Pukapuka and Tokelau. Coconut was the bulk of their diet, appearing at every meal as a drink, vegetable, dessert, or cooking oil. They ate pork, poultry, seafood, and produce, too, but the striking thing about their diet was the large amount of fat and saturated fat. On Tokelau, 57 percent of calories came from fat, about half of it saturated. On Pukapuka, they ate sixty-three grams of saturated fat daily and seven grams of unsaturated fat. Yet all the islanders were lean and healthy, with no signs of unhealthy cholesterol, atherosclerosis, or heart disease.

Then, by chance, nature presented an experiment. When crop failure forced Tokelau islanders to move to New Zealand, they ate less coconut oil, less fat, half as much saturated fat, and more polyunsaturated oils than at home. Good for the heart, right? But in 1981, Prior found his subjects living in New Zealand in worse health: the immigrants had higher cholesterol, higher LDL, and lower HDL.29 “The more an Islander takes on the ways of the West, the more prone he is to succumb to our degenerative diseases,” Prior said.

A few studies have cleared coconut oil of any role in heart disease, and recent research confirms those findings.30 In 2002, researchers fed people seventy to eighty grams of medium-chain fats or vegetable oils daily and found no differences in total cholesterol, VLDL, LDL, or HDL, or triglycerides.31 Other researchers who fed medium-chain fats to rats stated bluntly, “The lipid [fats] theory of arteriosclerosis is rejected.” They noted that Sri Lanka, where coconut oil is the main fat, had low mortality from heart disease.32

Coconut oil even improves the all-important ratio of HDL and LDL.33 A study of Malaysians who ate palm, coconut, or corn oil for five weeks found that coconut oil increased HDL, improving the ratio.34 In the same study, saturated palmitic acid (found in another tropical fat, palm oil) lowered total cholesterol and LDL.

How, then, did coconut oil get a bad reputation? Partly because we misunderstood cholesterol. We used to think that any fat that raised total cholesterol, as coconut oil can, was unhealthy, but now we know that total cholesterol is a poor predictor of heart disease and that raising HDL is good. Moreover, hydrogenated coconut oil was used in some studies. In 1996, the late lipids expert Mary Enig, an early and often lonely skeptic of the cholesterol theory of heart disease, explained that hydrogenation raises cholesterol: “Problems for coconut oil started four decades ago when researchers fed animals hydrogenated coconut oil purposefully altered to make it devoid of essential fatty acids. Animals fed hydrogenated coconut oil (as the only fat) became essential fatty acid-deficient; their cholesterol levels increased. Diets that cause an essential fatty acid deficiency always produce an increase in cholesterol.”35

In 2001, researchers reported that partially hydrogenated soybean oil was worse than coconut oil. “Epidemiological and experimental studies suggest that trans fatty acids increase risk more than do saturates because [trans fats] lower HDL,” they wrote. “Solid fats rich in lauric acids, such as tropical fats, appear to be preferable to trans fats in food manufacturing, where hard fats are indispensable.”36

Big food companies may not be rushing to put coconut oil back in crackers, but you can put fresh coconut, dried flakes, and coconut milk, cream, and oil in cookies, soups and curries, knowing it is good for your heart and gut. I take a spoonful of coconut oil daily to boost immunity. Coconut oil on my gums counters the bacteria which used to make them bleed. It is also a wonderful topical remedy for incipient yeast infections.

Coconut oil comes in three unofficial grades. The best is unrefined or virgin oil, made by shredding and cold-pressing coconut flesh while it is moist, a process called wet milling. The meat, milk, and oil are fermented for at least twenty-four hours while the water and oil separate. Finally, the oil is gently heated to remove moisture and filtered. Virgin oil has the lovely flavor and scent of coconut.

The second-best coconut oil is expeller-pressed and gently deodorized to remove scent and flavor; it’s a good choice if you eat coconut oil for health but don’t care for the flavor. Industrial coconut oil is made by extracting oil from copra, or dry coconut meat. To make it edible, the oil is refined, bleached, and deodorized, which destroys vitamins, scent, and flavor.

I buy virgin coconut oil, along with wonderful soaps and moisturizers. Virgin coconut oil isn’t cheap, but a little goes a long way, and it keeps well. Canned coconut milk is inexpensive. I like to have a couple of cans in the cupboard for making a simple, creamy soup made of equal parts chicken stock and coconut milk, with sautéed ginger and cayenne. It’s perfect in cold and flu season.