Meats and Small Game: The Foxfire Americana Library - Foxfire Students (2011)

FISHING

“I’d like to see just one more speckled trout.”

Iam not a native of Rabun County, but my mother’s family is. My family moved here when I was eight years old. One of the first things I came to realize about this county is the natural beauty that it holds. There are mountains and fields that have never been touched by human hands, and the numerous streams and lakes add to that beauty.

When I go fishing, I get a feeling I can’t describe. There is nothing like grabbing your fishing gear and going to spend a day trying to catch one of nature’s most beautiful inhabitants. It doesn’t matter if I catch a fish or not; I just love trying. That is the fun for me.

The individuals interviewed for this chapter enjoy fishing too. They do it now because they want to, but during the Depression many had to fish in order to have food on the table. Years ago, they had to fish with equipment like cane poles, string, pressed-out lead for sinkers, and, in some cases, pins for hooks.

People have told us about the time when there weren’t any limits on the number of fish you could catch in one day and of the times when you didn’t have to have a license to fish. That was before there was a danger of some of the native fish becoming extinct. Now the Department of Natural Resources (DNR) puts limits on the number and kind of fish you can catch. The designated limits vary from state to state and can change from year to year. The DNR also stocks the streams here; the fish are raised in a hatchery and released into streams and lakes, adding to the population of that body of water. People say they can taste and see the difference between native and stocked fish. Doug Adams, former president of the Rabun County Chapter of Trout Unlimited, told me, “Stocked trout can develop the same coloring and markings as a native trout within approximately seven months of release into a stream.” The one difference is the color of the meat. Native trout have a pink color to their meat almost like that of a salmon, whereas stocked trout do not have the coloring. Their meat is whitish.

Fishing has changed a great deal since the early to mid-1900s. But many secrets and techniques of previous generations are still applicable today and have been passed down to younger generations.

My granddad Buford Garner was an avid fisherman. He took my brother fishing many times and passed on his knowledge to him. My brother, in turn, passed that on to me. I never had the chance to go fishing with my granddad, but I feel that in a way I learned from him. And I’m proud to carry on his fishing knowledge.

—Robbie Bailey

TYPES OF FISH

There are numerous species of fish in the streams and lakes of North Georgia and western North Carolina. This chart lists the most common by type, family, and common name.

BASS

Black Bass

Largemouth—Bigmouth, Bucketmouth, Black, Green, Green Trout

Smallmouth—Bronze-back

Redeye—River Trout, Shoal Bass, River Bass

White Bass

Striped Bass—Rockfish

White Bass—Striped and Silver Bass

Sunfish

Bluegill—Bream

Redbreast Sunfish—Yellowbreast Sunfish, Shellcracker

Warmouth—Rock Bass, Redeye, Goggle-eye

CRAWFISH

Crayfish, Crawdad

EEL

CARP

SUCKER

White Sucker, Redhorse, Hog Sucker

PERCH

Yellow Perch

Ringed Perch, Yellow Bass

Walleye

Walleyed Pike, Walleyed Bass

TROUT

Brook Trout

Brookie, Mountain Trout, Native Trout, Speckled Trout, Speck

Brown Trout

German Brown, Speckled Trout

Rainbow Trout

Bow

Golden Trout

PIKE

Northern Pike

Pike

Chain Pickerel

Pickerel, Pike, Jack

CATFISH

Channel Catfish

Brown Bullheads

Bullhead, Mudcat

Blue Catfish

Channel Catfish

SCULPIN

Molly Craw Bottom, Craw Bottom

MINNOW

Shiner, Dace, Darter, Chub, True Minnow

CRAPPIE

Black and White—Calico Bass, Bridge Perch

HORNYHEAD

Knottyhead

NATIVE VS. STOCKED FISH

Stock, stocked, stocker, stockard, or hatchery fish are fish that were spawned and raised in a hatchery on processed feed, then stocked in a stream or lake. Wild, native, or original fish are fish spawned in the stream or lake and raised in the wild on natural foods.

There are no written records of when fish were first stocked in Rabun County. Doug Adams told us that brown trout were first brought to North America in the 1880s and released in Michigan. In the 1890s they were brought to the New England area, and the South received them in the early 1900s. The Chattooga River was the first body of water in Rabun County to receive brown trout, and rainbow trout were stocked shortly after the brown trout. According to Perry Thompson of the Lake Burton Fish Hatchery, there is no documentation of when trout were first stocked in Rabun County, but the DNR started intensively stocking trout in the late 1940s to early 1950s.

L. E. Craig explained the differences in appearance of native versus stocked fish. “You can tell the difference between the native rainbow trout and the stocked rainbow by the color. The native will be kind of a brownish color with a pretty rainbow down his side. The stocked ones will be just as black as tar when they put them in the creek. They’ll have a white streak instead of rainbow colors. The stocked brown trout will be kind of black-looking. Their spots won’t show up.”

Buck Carver emphatically stated that stocked fish were not fun to catch. “When they went to stocking with them blamed pond-raised fish, that took out all the fun of fishing for me! That took all the sport out of it! They bring them out of the fish hatchery and throw them in the river, and you stand there with your pole and catch ’em out just as fast as they throw ’em in it. Anybody can catch a fish when you step up to the bank and put the hook in the water. They know something’s coming for them to eat. They seen it around them ‘raring pools’ so many times, they don’t think about getting hooked. They’re not wild, and they’re not skittish.”

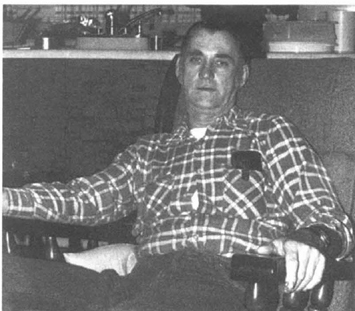

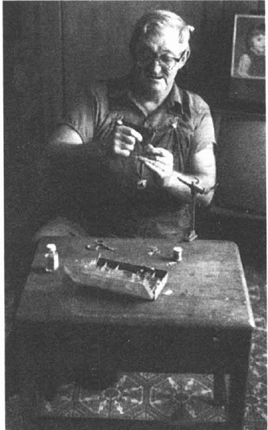

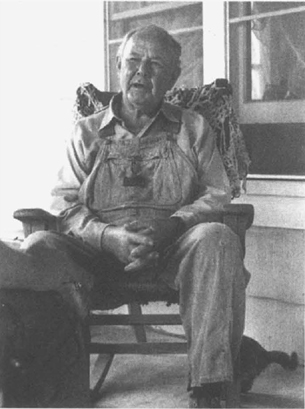

ILLUSTRATION 16 Andy Cope

Andy Cope told us it would take an expert fisherman to catch a native fish. “There are not many native fish anymore. They’re very few and far between. There are a few speckled trout deep in the heads of the streams, but so far back it’s hard to get to them. To go out camping a night or two in the woods and to catch some of those speckled trout, now, you can’t beat that, but as far as having a mess of fish to take home, that’s a rare thing. That probably won’t happen unless you’re a very special trout fisherman. Just anybody can’t catch them like that.

“I don’t think that the native fish taste any better than a fish grown in a pond. The Game and Fish Department used to feed the hatchery fish liver, and that’s what made the stocked fish in the lake mushylike. They don’t feed them that anymore. They feed them pellet feed now, made from grains and fish meal.”

Lawton Brooks stated, “A wild game fish is harder to catch and will put up a big fight when you get ahold of a good one. He’s wild, and you’ll have something on your hands. He does everything he can to break loose.

“There’s a few wild trout but not too many because they have so many roads to nearly all the streams. They’ve got to putting them old stock trout in streams, and the wild trout are just about gone. You’ve got to get a way back to get you a mess of wild trout.

“I don’t like to catch them stock fish too good. It’s kinda interesting but not like it is to get one of those wild fish. A stock fish is one that game wardens dump in the water. Stock will bite anything you throw in to ’em.”

Florence Brooks won’t eat a stocked fish. “Native fish got a pretty color, and their meat is firm. Sometimes you’ll catch these stock fish, and they’ll turn white-spotted before you get ’em home. Their meat’s real soft. They keep ’em in these big vats, and they feed ’em chicken feed before they turn them loose in the lakes. The native fish don’t do that. They just eat what they can catch, and they are stronger, firmer, meat and all. The minute those stock fish that I’ve caught turn white-spotted, I throw ’em away. I don’t like them white spots.”

According to Parker Robinson, “Fishing is my favorite sport. I really love to trout fish, but it’s hard work. I’d rather catch them than the others, but it’s rough. This day and time you have to get off the road a little and out away where people don’t fish so much. I go down the creek kind of in the roughs, and I catch some pretty nice trout. Natives [trout] are smart fish, ’specially if they’ve been fished after. Rainbow is the best eating trout, I guess.”

Talmadge York explained to us, “German brown trout were brought here and stocked. Same way with rainbow, brook, bream, and bass. They were brought in and stocked in the lakes. They used to stock some brown trout here, raise ’em over at the hatchery and stock ’em, but they didn’t do well in these small streams.

“Brown trout are sharp fish. They can see you a long way off. They’ll put up a fight, and they’ll get off your hook after you’ve caught ’em. Brown trout have big red spots on them, from their tails to their heads, about the size of dimes when they get to be about twenty-three inches long. Just as red and pretty as you’ve ever seen.”

L. E. Craig said, “And a lot of people call a brown trout a speckled trout. Brown trout are, but they’re not the original speckled trout. I can tell one just as quick as I see it. The brown will be kind of black-looking. Their spots won’t show up. A brown trout is pretty, and if you ever see a big brown, it’ll have red spots on it.”

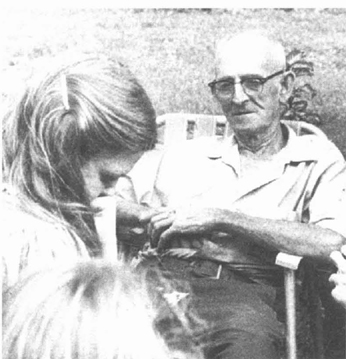

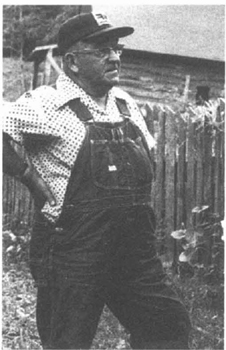

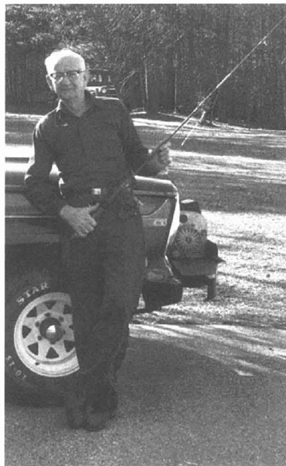

ILLUSTRATION 17 Willie Underwood

Willie Underwood reminisced, “The first rainbow trout in this section here was shipped here in a barrel when I was six or seven years old. Now there are rainbow in nearly all the streams.”

KINDS OF TROUT

“Mountain trout spawn in February and rainbow generally in the spring [February to April]. You ain’t supposed to be fishing then,” Parker Robinson said. “You take these mountain trout here. Now they’ll have a winter coat on them. They don’t have scales on them. It’s right along now, the beginning of February, when they begin to lay eggs, and they’re getting a thick coat on them. If you catch two when they’re like that, and let them be against one another and they dry a bit, it’s just like glue. You can hardly pull ’em apart, and you can hardly get that coat off of there when you’re trying to clean them. I never would eat ’em when they had that coat on them, that spawning coat that mountain trout have.”

Talmadge York told us, “We used to fish in these little ol’ trout streams for specks. Original specks [native speckled trout] won’t get but about six inches long. That’s all. They don’t have no scales on them at all. They’re just as slick as a catfish.”

Willie Underwood shared with us his feelings about why there aren’t many speckled trout left in Rabun County. “The speckled trout is a small species. They don’t have scales but do have little specks on them. There are only a few in the streams because they have to have more oxygen than anything else. It’s got to be pure, clear water. The speckled trout are a thing of the past. There has been so much pollution in this clear water, and the lakes have been fished so heavy, the speckled trout are just nonexistent now. Speckled trout cannot compete with the fish that eat one another.”

L. E. Craig agreed with Willie Underwood. “I don’t know where a creek in this country is that’s got any speckled trout. They can’t stand for one bit of mud, silt, or anything [to be in the water]. I’d like to see just one more speckled trout. They are the best eating fish. A lot of people call brown trout a speckled trout, but they’re not.”

Andy Cope, who owned a trout fishing resort, told us, “Brown trout is a stream trout. It’s not a good trout to grow in lakes and ponds. They bite slower than the other trout, and that’s why there are some large brown trout caught in our streams. The main Betty’s Creek stream is stocked with brown trout by the Game and Fish Department.”

Jake Waldroop explained, “The brown trout doesn’t have any scales, and he’s brown all over. I’ve fished for the brown trout. They grow big. I caught one out there in the creek by my house that weighs three and a half pounds. Got him in the freezer right now.”

FISHING EQUIPMENT

The fishing equipment of today is fancy but fairly easy to use. Yet it wasn’t always easy to get fishing equipment. Some people made their own fishing poles out of cane or bamboo, their lines out of horsehair or string, and their sinkers from a piece of lead beaten out thin and folded around their line. People back then had it hard just to go fishing.

Willie Underwood explained the basic equipment. “Our fishing poles would be made out of creek canes, alder bushes, sourwood, or whatever we had.

“Fly rods have been around for years, but they wasn’t used in this area until after the Depression. Fly rods was for people that had money. People didn’t have them much around here because they couldn’t afford them. I was forty years old when I got my first fly rod, and I bought it myself.”

Melvin Taylor told us, “My daddy used a cane pole, and that’s what I started fishing with. The people that had a lot of money had a reel and rod. The rest had cane poles, which you can find on creek banks.

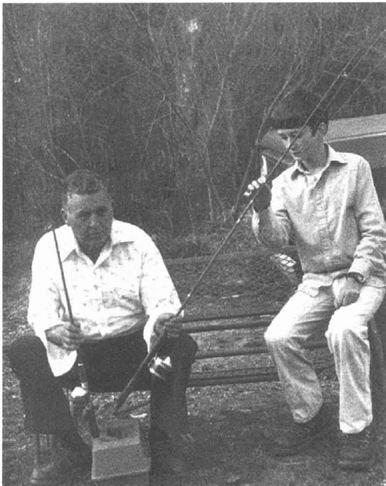

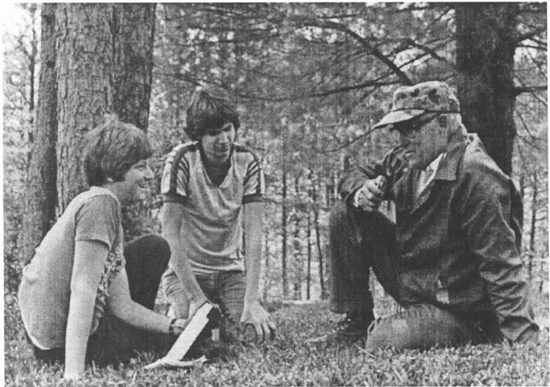

ILLUSTRATION 18 “My daddy used a cane pole, and that’s what I started fishing with.”—Melvin Taylor

“Daddy caught bass that weighed eight and a half pounds with a cane pole. That’s the biggest fish I could remember. It came out of Burton Lake. Boy! They put it in a tub at that store on display. That one was a whopper on a cane pole! That’s the biggest I’ve ever heard of.”

Andy Cope said, “We would make our fishing poles out of birch saplings. We’d cut a birch sapling and peel the bark off it, then hang it up by the fire and let it dry. When it was dry, we would use it for a fishing pole. Sometimes folks who lived in an area where there was a river would get river cane poles. Where I grew up, there wasn’t any river cane.”

“Years ago, I used to fish with a cane pole—only thing we had to fish with,” L. E. Craig remembered. “There wasn’t much bamboo in this country, but you could buy ’em at almost any store for a dime—big, long-tipped ones. Boy! You could catch bass on that thing that weighed two or three pounds. You talk about sport! It was! Have your line just about as long as your pole.

“I used to go down to Seed Lake in a boat and catch eighteen or twenty bass in a couple of hours. Bream could make your line whistle if they got on your pole. A few people had level winding reels to cast for bass.”

Jake Waldroop said, “We would make our own fishing poles. Mostly, we would get out there and hunt us a little straight hickory. Hemlock, black gum, and hickory was hard to get. I would always prefer a cane if I could get it. Cane is almost like bamboo.

“I have made lots of cane poles. We would go to the Little Tennessee River and cut sometimes ten or fifteen of them, take them home, and hang them up by a string in the barn. We would cut them off the length we wanted them and tie a great big rock, three or four pounds, to them and let them hang there. Keep ’em from crooking up. Keeps ’em straight as a gun barrel and makes good fishing poles. If you didn’t hang ’em up and put a weight on them, they would be warped. The pole should be a little bit bigger than my thumb by the time it’s through hanging up. The tip will be as little as a knitting needle, but it will be strong. We could always get them from eight to ten feet long. A cane pole is hard to beat!”

Talmadge York reminisces, “Back when I was a boy, we made our line. We’d take a spool of thread and double it and beeswax ’em. And then we used to use what they called a silk line. You could buy lines made of silk before plastic came out.”

Willie Underwood told us, “We used to use sewing thread off a spool for fishing string. It would break easy, so you would have to double and twist it. Sometimes we’d twist it four times because the lines weren’t that long. We just had poles. We didn’t have any reels to put it on. We’d buy standard fishing hooks at the store, but we didn’t have fishing floats like we do now.”

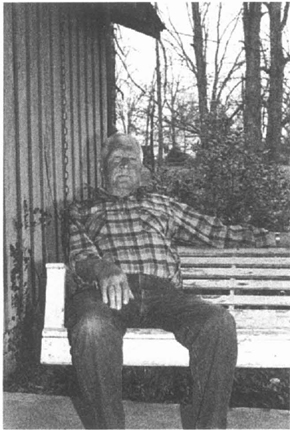

ILLUSTRATION 19 Minyard Conner

Minyard Conner said, “I can remember when I used to fish with horsehair for a line. All you would have to do to it was twist some horsehairs together. You had to have a good smooth place to make ’em. Put them horsehairs on your leg and rub them. That’ll twist ’em together, and then when you want to set another one in there, just stick it in and keep a-rolling. They just roll on out there—make it as long as you want—and not have a knot in it. It’ll hold too, about three or four horsehairs twisted together. Some of them would put four or five horsehairs together to catch a big fish. A three-horsehair line will catch a twelve-inch rainbow. I’d say it’s six-pound test leader.

“Put a sinker on your horsehair line to fish underwater. A horsehair won’t tangle up like your other lines. If you throw it over a limb, it might wrap around it three or four times, but you give it a little pull, and it’ll unravel by itself, and it’s straight. You take a cotton string and throw it around a limb, and it ties right there.”

Jake Waldroop recalled, “Sometimes we would buy hooks and tie them to the line, and sometimes we’d get them already made with the leader tied to them. Sometimes it’s faster getting the hook out of the fish’s mouth, if you can fish with bait with a sinker. ’Cause if they’re bitin’ good, when he grabs the bait, he’ll just swallow hook and bait plumb down, and I have had to tear a fish’s whole mouth open to get the hook out.”

Leonard Jones told us about an alternative to using store-bought hooks. “I know one feller that said he wasn’t never able to buy him no hooks. He’d fish with a straight pin. He’d bend it, you know. It didn’t have that barb, and when he hooked one, he had to throw it out on the bank. If he didn’t, it’d come off, and he’d lose it.”

Leonard also explained how to make homemade sinkers. “Before they got to making sinkers, you’d just get you a piece of lead, cut it in strips, beat it out right thin, and then roll it around the line. You can buy any size sinkers now, great big ones or small ones. You want a sinker on it if you’re fishing with bait, but if you’re fishing with a fly, you don’t.”

Andy Cope recalls, “We used store-bought hooks, but we made our own sinkers out of shot from a shotgun shell. It was folded and put in a big spoon and melted on a fire. That run the lead together. Then we’d hammer the lead out flat and cut it into little pieces and roll it around fishing line for sinkers.”

Talmadge York told us how to fix up a trotline. “To make a trotline, first tie the hooks to two-foot lengths of string. Then tie these to a long piece of binder twice about six or eight feet apart to keep the hooks from getting tangled up. Then go to a good root or something on the edge of the lake and tie one end of the line to that. Take your boat across the lake, maybe a hundred yards, somewhere where the lake’s not too wide, and have the other end of your line tied to a big rock. If you don’t tie the string to a big rock, it’ll stay right on top. Put it down to where it’ll be four or five foot under the water.

“I have set ’em and gone back the next morning, and every bait was still on. You work two or three hours to fix one up and set it and then go back and don’t get nothing—that’s hard work. I just quit fooling with it.”

Leonard Jones explained what to do with the fish you catch. “I use a stringer instead of a chain to put the fish I catch on. All you do is run the line up through the gills and out their mouths. The first one that you put on, you’ve got to run it back through, make a ring. The rest is just strung through the gills and out the mouth without having to make the ring. You carry your stringer along with you, but most of the time you’re setting down somewhere. So just throw your fish out in the water and take the end that has the sharp metal cover and stick it down in the ground. That’ll hold ’em.”

BAIT

“Trout will eat crawfish,” L. E. Craig told us. “If you ever clean a trout of any size, and you don’t find one in him, there’s something wrong. Nearly any kind of fish will bite a crawfish. If he sees one, he wants to get him. Boy! It hurts to get bit by a crawfish.”

Minyard Conner informed us that “minnows are good bait, but they don’t live long.” Talmadge York added, “I used to fish in the lake with minnows, and I fished for crappie with them. I reckon minnows are the only thing crappies will bite.”

Lots of fishermen think red worms are the best bait. Jake Waldroop told us, “Red worms are good bait. Sometimes I have caught six fish with one red worm. I’ve tried them all, and red worms are the best.” Buck Carver believes that “trout will all bite red worms in the wintertime and the early spring, but not all year round. They’ll go for flies a lot of the year.” Melvin Taylor told us, “Bass bites red worms and night crawlers real well in the spring. They’re better than a lizard anytime.” And Lawton Brooks said, “Red worms are pretty good for wild trout. Just regular earthworms. Them little ol’ speckled trout—you can catch them with those worms. Just pitch a little ol’ worm over there where the water ain’t real deep. He’ll come up and bite that worm, and you don’t know where he come from.”

Willie Underwood recalled, “We’d catch those ol’ black crickets that you see in the fields, but that was hard to do. They’re good for trout.”

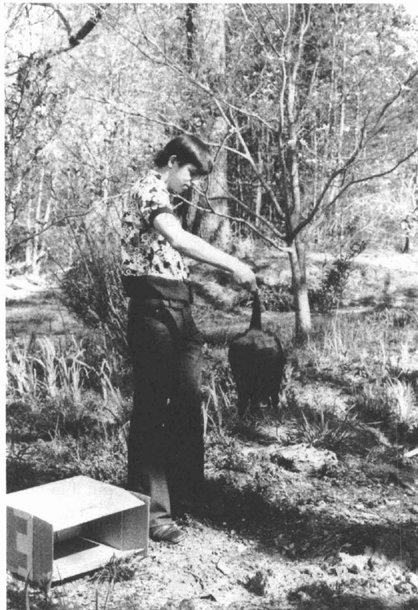

ILLUSTRATION 20 Carl Dills

Carl Dills told us about flies used by fishermen. “These old mountain people calls ’em stick bait, but the regular name for them is caddis fly. They live among sticks and rocks in the edge of the creek, and you just pull them out.”

Lots of fishermen preferred night crawlers. Blanche Harkins told us how her sons caught them. “My sons uses night crawlers and red worms. Night crawlers come out at night, and fishermen catch ’em. They’re just like red worms but a whole lot larger. The later at night they wait to catch them, the more they come out. If you wait till real late, they’ll be out on top of the ground, and you can just pick them up. You use a flashlight, and if you don’t dim your light, they jump back in their holes.”

Parker Robinson explained how to create a “bed” for night crawlers. “You can make a place in your yard to raise night crawlers by putting your food peels in a pile. That dirt’s gonna be rich where you have all that stuff, and your worms will come to that.”

Willie Underwood told us to “burn a hornets’ nest or yellow jackets’ nest and get the young larvae. They make awful good bait, but they’re tender enough that if you don’t catch your fish when he first hits that bait, you’ll have to bait your hook again.”

Talmadge York told us about some of the different baits he uses. “I have got these little fellers [hellgrammites] out from under rocks and fished for trout with ’em. They’ll sting you if you don’t catch ’em just right. They look like a great big worm. We used them for when we trawled for bass. You can find what they call stretcher worms in the edge of the water.”

Jack Waldroop recalled using mayflies as bait. “That’s a fly that’s down in the water. When he begins to come on top of the water and starts trying to fly, them fish come up to eat him. I’ve seen seventy-five to one hundred fish coming up at one time for those flies when they started hatching out. If you put a different kind of bait in there when the mayflies are in season, the fish won’t strike as much. Just about all fish like mayflies.”

Buck Carver reminisced about using wood sawyers. “The best luck I’ve had on a sinker or an eagle claw snail was these big ol’ white sawyers that you get out of trestle timber. Used to, they would repair these railroad tracks and would throw out the old timber, and them of big sawyers would get in there. A sawyer is a termite-type worm. They’ll be anywhere from a quarter of an inch to three or four inches long. Sometimes you can find them in rotten pine logs.”

Another kind of worm used was the catawba worm. Minyard Conner told us, “The old catawba worms that are on the catawba trees—they’re good bait. You’ll never find the catawba worms on any other tree, just that certain kind.”

Talmadge York agreed that those worms were good bait, especially for bream. “Old pea trees is what we call the trees they grow off of. There’s another name for them but we always called ’em a pea tree. They have big of long peas on ’em. Bream bite catawba worms pretty good. Take a little stick or match and turn him wrong side outward. Take his head and push him plumb through. When he turns out, he’s white. They’ll bite him better white than green. If you fish with them, you usually catch big bream. Little ones won’t fool with ’em.”

Many fishermen used lizards for bait. Talmadge York recalled, “I have fished with what they call a red dog. It’s a type of lizard except he’s redder, like blood. They are good to fish with for bass. We used to go spring lizard hunting and stay out ’til twelve or one o’clock if we were going fishing the next day. You’d tear your fingers all to pieces scratching under rocks and catching them with a flashlight. Them spring lizards are awful good bait for bass if you fish slow with ’em. You get more big ones that way because the little ones don’t pay much attention to the lizards.”

L. E. Craig told us he used spring lizards to catch the biggest fish he ever caught. “I like to use spring lizards for bait. I don’t like artificial bait. The largest fish I ever caught weighed seven and a half pounds, and I was using spring lizards. I’ve caught lots of trout with little-bitty lizards about two inches long. Bream and trout bite them small lizards you get out of a spring. Them ol’ lizards live for half a day almost.”

Jake Waldroop described using chicken parts for bait. “A good thing to bait your hook with for trout is chicken innards. Just throw a great big wad of them out in the water. Directly a fish will come and get ’em and start dragging them off. All you got to do is drag your fish out.”

Corn is commonly used here to attract stocked fish. Jake Waldroop recalled, “Corn is good bait. Put a little red worm on a hook and then put a piece of corn on after it. Throw your line out there, and the stocked fish will come right for it. You can catch them better than natives with corn. The natives don’t care too much about that corn.”

Talmadge York told us, “Here, lately, the stocked fish bite corn better than anything, whole-kernel corn. The reason they bite this whole-kernel corn is because they’ve been fed on pellets, and they’re used to that.”

Many fishermen debate the use of artificial or real bait. Talmadge York told us, “I’d rather use artificial bait because it’s less trouble. Fish bite ’em just as good. At times, I believe they hit ’em better. I’ve been fishing with boys that’s been fishing with ’em while I was using live bait, and they’d catch ’em out of a hole where I wouldn’t.”

Carl Dills disagreed. “Fish go after live bait better than they do artificial bait. It’s like if you went down here to the cafe, and you ordered a steak and they brought you a hot dog, you’d tell them you wouldn’t take it. A fish is smart. They don’t grow up to be twenty, twenty-five inches biting every hook that comes along either. They get smart as they grow. A big trout hardly ever feeds himself of a night. Once in a while, he’ll bite, usually if you use a big enough tackle to hole ’im.”

Other fishermen change bait as needed, depending on what the fish are biting. Buck Carver said, “When you find a good fishing hole, and one day you come down there and throw your hook in, and they don’t bite, you know that they’ve got tired of the same ol’ thing. Fish are just like women—they change their minds all the time.”

ILLUSTRATION 21 “When you find a good fishing hole, and one day you come down there and throw your hook in, and they don’t bite, you know that they’ve got tired of the same ol’ thing.”—Buck Carver

FISHING BY THE SIGNS

Many of the old-timers believe the signs of the zodiac play a part in whether or not the fish will bite. Buck Carver recalled, “Different times of the moon makes a lot of difference when you’re fishing. When the sign is in the heart, they will bite better than usual.

“I tell you what you can do at home. Find a bottle like a small Coca-Cola bottle that’s round and fill it to the top with water. Place the bottle upside down into a glass. When the water in the bottle rises in the glass up to the neck of the bottle, get your hooks and go!”

Leonard Jones doesn’t follow the signs when fishing. “Lots of people go by the signs of the moon, but I never did pay it much attention, just to be honest with you. I go anytime. There’s days you can go out there, and I don’t care what kind of bait you’ve got. They won’t bite. There’s times you can go, and they’ll bite like anything. Now, I don’t know what causes it, whether it’s the signs or what. Lots of people notices the signs to a great extent. I never did pay much attention to them.”

Talmadge York agreed. “I don’t go by the signs. But now I believe that on a dark night is the best time to fish. I don’t mean to fish on the dark night, but just that time of the month when the moon is not shining bright. It seems like when there is a light night, the fish feed all night, and they’re not hungry the next day. They take it by spells. When they’re feeding, you couldn’t catch a one. It’d be just like there’s not a fish in the water.”

FISHING TECHNIQUES

All the people we talked to had different ideas about the way they caught fish and what worked best for them. We asked each fisherman to tell how he caught the kinds of fish he does and any methods he recommends.

Lawton Brooks told us, “Crappie will bite in one place for a while, and then they’ll quit. They move a lot. They move in schools like white bass. If you get in a bunch of crappie, and they start biting good, the first one you catch in the lip where it won’t hurt him, ease him up and cut the line, leaving your hook in him. Cut you off a little bit of leader and tie it to a lightbulb and just drop it back in the water, and he’ll stay with the gang. Watch where the lightbulb goes, and just take your boat and follow him. Just keep a-catching them because he will follow the gang of crappies, and you will know where the fish are.

“I’ll tell you about a catfish. He’s so slow about biting. Maybe you’ll set there for hours before one ever bites. Maybe you’ll catch one, and sometimes you’ll be there the rest of the day and night and not catch nothing. I haven’t caught but two catfish in my life in the daytime. Caught one of them out of Hiawassee Lake and caught the other one down here above Tallulah Falls. I went down to Tugalo one time with another feller and caught a bunch of little catfish about four inches long. It wasn’t interesting. They was too small to eat.”

“Anytime my wife will let me go fishing is the best time to go,” Carl Dills declared. “When I get all my work done and she’ll let me—that’s the best time. You take one of the dark nights. The fish will bite better in the daytime than they will of a light night. I reckon they feed more when the moon is shining all night long than they do of a dark night.

“When it’s raining, it washes out the food into the water, and they’ll go to feeding. There’s a certain time a fish will go to feeding, and other times you swear there wasn’t a fish in the creek. Then in maybe ten minutes, there’s fish everywhere you look.

“You take a catfish. It feeds by smell, and they’ll bite when the water’s muddy quicker than when it’s clear. A bass or a trout feeds by sight, not by smell alone, and they bite better when the water’s clear. Dark water that’s dingy, though, and using night crawlers, trout will bite ’cause they’re looking for worms that’s washed in the water from a heavy rain. They’re out there looking for ’em.”

Parker Robinson revealed some of the secrets to his successful fishing. “I like to use two fishing poles because I’ll be trying to catch one on one pole and maybe another one would bite the other. I like to fish from land because I can catch more fish, but they’re about the same size you’d catch from a boat. I don’t like to fish in the wintertime because you can’t catch much. You can catch more fish when it’s not raining, but it don’t matter if it’s cloudy.”

Buck Carver informed us, “When you get to the headwaters of these little trout streams, and the water is extremely clear, I like to wade downstream because that stirs up the mud, and fish in their holes can’t see you. You can catch more going downstream than you will going up.

ILLUSTRATION 22 “I like to use two fishing poles, because I’ll be trying to catch one on one pole and maybe another one would bite the other.”—Parker Robinson

“When you’re fishing for native trout, fish uphill. There’ll be one laying out on guard duty at the bottom of the hole. If you can, slip up behind him and throw out the hook above him and let it drift down to him. If you can get that one on guard duty, you’ll be able to catch two or three more out of that same hole. But if he sees you and sails into that hole, you’re lucky if you get any of ’em ’cause he comes in there so fast, the rest of ’em knows that he’s done set the alarm. They ain’t fools. If one comes in there like a scalded dog, the others in that hole knows there’s a dead cat on the line somewhere.”

Leonard Jones stated, “A good time to go fishing is when it’s raining, if you [don’t mind] getting wet. They’ll bite as good or better than they will any other time. I think maybe the rain causes the water to rise, and they learn that when the water rises, it washes in stuff for them to eat. When it commences to raining, they get to stirring around, and the more they stir, the apter you are of catching them.

“You take the bream. They go in droves around. Maybe you’ll catch several right now, and then they’ll be gone for a while, then come back around, and you’ll catch another bunch. They don’t stay long at the same place. Now, a big ol’ trout, if he’s got a certain hole in the river, he’ll stay there most of the time in that same place.

“You should go fishing early of a morning or late of a evening. You can catch trout or catfish at night. From daylight ’til nine in the morning, you’ll catch more fish than you will the rest of the day ’til about five or six that evening. Any kind of fish will bite a heap better early of a morning or late of a evening. They don’t bite too awful good at noon. They’ll bite some along and along all day. When it gets on up about the Fourth of July when it gets real hot, they don’t bite good at all. They’ll bite in the winter if you can stand to stay out there and fish, but you freeze to death. I caught bream one time up yonder on Bear Creek Lake ’til I got so cold baiting my hook that I got to where I didn’t have no feeling nearly in my hands. Every time I’d throw my hook in, one would bite it. I just kept fishing ’til I froze myself good before I quit.

“In the wintertime, fish eat anything they can get. If a lake has been down and rises, why, that washes in a lot of food.”

Melvin Taylor believes the best time to fish is when it’s calm. “I don’t remember me doing much good when it was cloudy with the wind blowing and white clouds in the sky, but that’s the time my daddy said was best. I say the best time is when it’s clear and calm. The spring of the year or fall is better than any other time for bream fishing.

“A good place to fish is where the stream runs into another one. In the spring of the year, they’re looking for a place to bed. That’s when you’ll catch most of the trout. They bed on a full moon, when it’s warm. They’ll be out in the shallow water, so you just travel out ’til you find their beds. Then stop and fish until they stop biting. They’ll just bite for so long. Then you just crank up and find another bed. You can see the beds in early morning, but still you can see them plain as day in shallow water in the evening.

“Bream fish, that’s my favorite kind of fishing. One thing about it, you can always catch one of them. They bed on every new moon. In the spring of the year, you get some red worms and go on a new moon and ride around in your boat until you find a bed. If you find them in a bed, you can catch them.

“When you’re out there, you don’t necessarily have to be quiet, but the aluminum boats have to be pretty still because of the vibrations from them. The bass, they won’t hear you coming up. You can just about run across them. I’ve ran right over a bed and not even seen them.

“A good time to go catfishin’ is when it’s dark. They go to feeding then.”

Jake Waldroop shared his fishing techniques. “It’s better to catch fish early in the morning or late in the evening. Now, rainbow bite better of a night than of a day. I remember the time when they would just eat you up at night.

“I would rather fish upstream when fly-fishing. When you’re fishing upstream, just let your line float back downriver.

“It don’t take a person long to learn how to catch a fish. By the time you go fishing four or five times, you get along pretty good. You can just sit on the side of the bank and fish out in the water and catch them. Let your hook come around the edge of the bank. He’ll be laying back under there. He’ll run out and grab it. You take that net, and when you hook one out in the water somewhere, you can pull him up to you on the pole and reach out with the net and get it under him. Lots of times, if you don’t have that net, he will float off the hook.

“You have to throw them back in now if they’re under seven inches long. It doesn’t hurt a fish much usually, but if you hook him pretty deep, you just might as well throw him on the bank. If you just catch him in the lips, you can throw him back in.

“I’ve had a lot of fish to get away. If you can miss him, that’s about it. If you hook him a little, you can tell it, you can feel it. If he struck at your hook, if you didn’t snag him, he may not come back again. About nine times out of ten, you will miss one.

“When I was a boy, and we went fishing, we had to walk about four miles, but when we got over there, we fished for about two hours and then went back home. Sometimes we would go and stay all night. When we did that, we would just fix us a mess for supper and breakfast. Then after breakfast, we would go back and catch us some fish to bring home with us. Sometimes we went on Monday morning and didn’t come back ’til Saturday. We would stay a whole week at a time.

“You don’t have to be too quick when the water is right clear. It’s best for you to keep the bushes between you and the hole you fish in. Back then, there was so many they couldn’t help from biting. They didn’t pay much attention to you. It still don’t take too long to catch a fish. I just walk up to a hole, have my hook baited, and throw it in. Jerk it right back out of that. Those trout, when they bite, they really come after it. You don’t have to wait on them too long.”

FAVORITE FISHING HOLES

“My favorite place to fish is down on the Chattooga River,” said Talmadge York. “Anywhere you can get to in the Chattooga is a good place. Sara’s Creek is a good place in the summertime. There’s so many people fishing there now that there ain’t many fish left. For the last few years, me and my wife have camped up there at Sara’s Creek—stay a week at a time. When they stock ’em up there, you can catch ’em right when they first put ’em in. We always catch our limit. Have enough to do us. It ain’t so much fun catching them stocked ones as it is catching the wild ones, though.”

Melvin Taylor prefers lake fishing. “The best fishing place is Lake Rabun. If you want to catch fish—fish Lake Rabun. They’ve got ’em all. It’s the best fishing place you’ll find. If you want to catch bream, you go to Lake Rabun anytime in warm weather up into October and November. In fact, I caught a mess down there during deer season.”

Florence Brooks prefers fishing in streams. “I’d rather fish in a stream because you can just catch them better, and then I just like stream fishing. We used to walk from Rabun Gap to the head of Betty’s Creek and then fish back down. We’d catch a pile of fish! Walk along, and if you feel something, jerk it. But in a lake, you just stand still, wait for them to get on, then jerk it. I fish right around here, all over Rabun County, just anywhere I can get a hook in the water.”

ILLUSTRATION 23 Florence and Lawton Brooks holding their fishing trophies

Lawton Brooks agrees with his wife. “I like to fish anywhere there’s a good stream. I like to fish streams better than I do lakes because there is more sport in it. Just get in there with them. Trout have more action. Give you more sport.”

Jake Waldroop said, “I never did have a favorite fishing hole. Everybody could locate them just as well as I could. There is lots of rivers that runs right under these mountains here. There’s Long Branch, Park Creek, Kimsey Creek [North Carolina]. I would rather fish in them than any other. I have caught lots of fish from them.”

Minyard Conner told us, “I like to fish almost anywhere. I don’t like fishing in trout farms much. I’d rather fish after a trout where it’s raised out in the wild where you just have to outwit him to get him. If he sees the shadow of your pole, he’ll run. He knows something dangerous is on hand.”

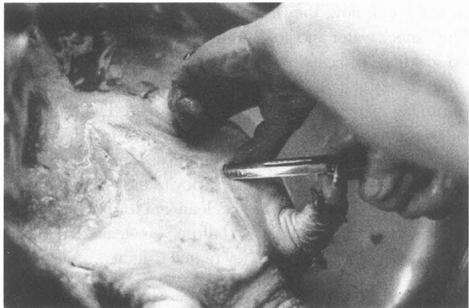

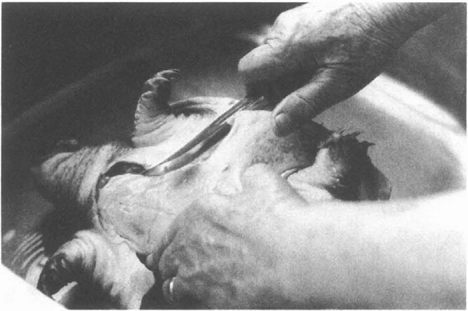

CLEANING FISH

Leonard Jones explained, “It depends on what kind of fish you have as to how you clean it. If they’re small, take a trout for instance, I just scrape them good, take their innards out, and cut their heads and fins off.

“You have to skin a catfish. It ain’t got no scales on it. Cut it around the neck, split it down the back and stomach, and take a pair of pliers and pull that skin off. You can skin ’em just about as quick as you scrape ’em. If I catch a great big fish of any kind, I skin it. Small ones, I don’t.”

Minyard Conner told us, “To clean a speckled trout, just take a knife and split him open and take his guts out. Then he’s ready to cook.”

Buck Carver said, “The rainbow and the brown trout have scales, and you have to scrape them. Though the speckled trout has scales, they’re so fine you needn’t try to scale him. All you do is rub that slime off with some sand.”

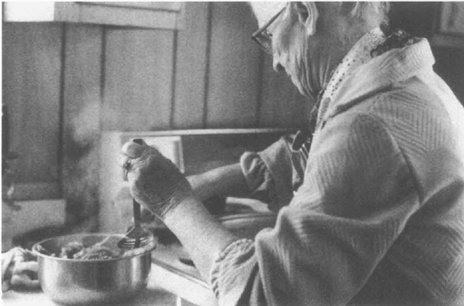

COOKING OR PRESERVING FISH

Minyard Conner stated, “There are a lot of ways you can cook trout—bake ’em, fry ’em, or stew ’em. First, you cut their heads off and clean ’em. Now, these stockards [stocked fish], I’d stew ’em and take the bones out and make fish patties out of them because their meat’s too tender to hold together to fry.

“To bake a fish, you coat them with a little grease and lemon juice. Heat your oven to about 350 degrees and cook ’em about thirty minutes.”

Florence Brooks told us, “Mama used to fry fish for us for breakfast. Nowadays I usually give away what I catch, because we don’t eat fish. When I do cook them, I just roll the fish in cornmeal and a little salt and fry them in grease on the stove. Some people can’t eat fried fish, but my kids just like them fried brown. They eat them that way with hush puppies.”

Minyard Conner revealed, “I’ve eat fish eggs! I’ve caught a lot of big fish with big rolls of eggs under them. Boy, I like them! That’s caviar! That’s good!”

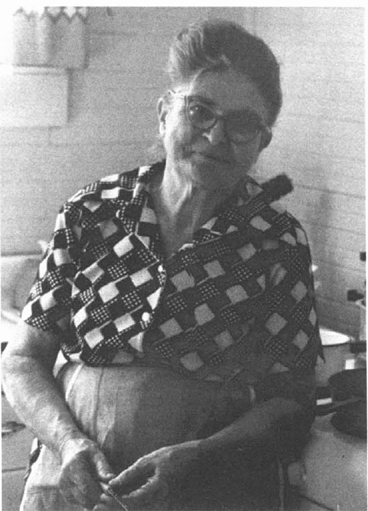

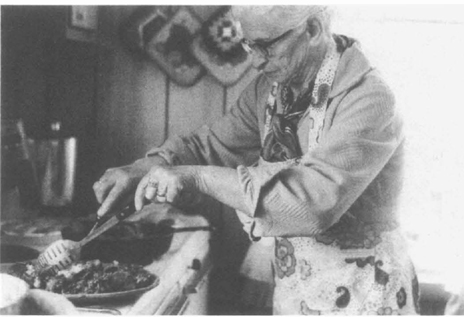

ILLUSTRATION 24 Blanche Harkins

Blanche Harkins stated, “Trout are easy to cook. I scrub them with a scrub pad or dishrag gourd to get the slime off. Then I cut their heads off and cut their stomachs open to take their innards out. Then I wash ’em again and roll them in cornmeal. I have a big black frying pan that I put Crisco in and get it hot enough to smoke. I turn the heat down some and brown them about ten minutes on either side, and they’re ready to eat.”

Jake Waldroop told us, “Before we had a freezer, we had some cool springs, and we would put any fish we weren’t going to cook right then in a bucket or half-gallon jars and stand them under those springs where the cold water would run over them. We could keep them for four or five days or more.”

Minyard Conner recalled, “Well, I was raised with the Indians. They wouldn’t do like the white man. You know, catch too many of anything and have to throw ’em away. They’d just catch what they could eat, and that’s all they took. If they could eat ten, then that’s all they took. They didn’t usually try to preserve them. They didn’t do a thing with ’em.”

“THE BIGGEST FISH I EVER CAUGHT”

Florence Brooks related, “The biggest fish I ever caught lacked one inch from being two feet long. It’s been ten or fifteen years ago, I guess, when we lived at Dillard. I caught a brown trout right about Betty’s Creek Bridge. It was as long as my arm and weighed four pounds and a half. I was using an ol’ cane pole, and my line had been on there no telling how long.

“They all took a fit when I caught that fish—thought somebody was a-drowning! I had it caught deep in its throat, and it couldn’t cut up a bit. I just drug it to the bank. Lawton [her husband] and Kent Shope got down in the water and lifted it up on the bank with their hands.”

Minyard Conner stated, “The biggest fish I ever caught was a twenty-four-inch rainbow over in Smokemont, in the Smokies [North Carolina]. I have fished all year long and maybe not caught one fish over a foot long. I seen one over there in the Smokies that was thirty-six and a half inches long that they’d caught in the Pigeon River.”

Talmadge York recollected, “I never had a really big fish that got away. One maybe twelve or fifteen inches long got off before I could get him out of the water. About the biggest fish I ever caught was a twenty-three-inch brown trout. I caught a blue cat one time that weighed nine pounds. I guess the biggest bass we ever caught was about a six-pounder.”

“I’VE HEARD, WHAT GROWS THE FASTEST OF ANYTHING IN THE WORLD IS A FISH AFTER IT’S CAUGHT ’TIL YOU TELL ABOUT IT.”

The first thing we thought about when we decided on an entire chapter dedicated to fishing were the stories fishermen are reputed to tell. The main focus of all our interviews was probably “Do you know any good fishing stories?”

Some of these are events that happened to people as they fished, or stories that had been told to them about people fishing, or stories they know about other fishermen. Some of the stories are exciting; some are funny; some are kind of hard to believe but are said to be true; and some are just informative.

Lawton Brooks told us, “I found this fish, oh, I guess four or five months ahead of the time I caught him. But I couldn’t get him to hit nothing. I tried everything. My wife’d catch lizards, and we’d try those. I didn’t tell nobody where I fished at. It was right down the railroad going by our house. The creek went right in beside the mountain there, hit a big rock, and turned back right under the rock there. It was right deep, and it was swift through there. It might be that when you put your bait in there, it went by too fast for him to catch it. He didn’t want to fool with it or something.

“I’d slip down there sometimes and see him out. I’d look over in there, and sometimes he’d be in a deep hole. I’d go to the house and tell Florence, my wife, ‘I’m gonna catch him.’

“So they started a revival meeting down there at the church below the house. One evening—it was the prettiest evening to fish—I went out there, and I fished and I fished, and fooled around and caught me a little ol’ crawdad. I cut his head off, hooked him on that hook, and had me a line—I mean a stout’un. I had me a big ol’ cane pole, long as from here to the door yonder, and I put that thing on that pole. I put me on a great big ol’ beaten-out piece of lead, and I rolled it around there.

“I throwed that line right on over in there with that crawdad, and I went on off to church. I put the pole up under a rock and stuck it in the bank. We come on back, and he’d bit my line. He was on there!

“I tell you what I done. I’d pull him out from under that rock, and he’d go back. And I’d get him back out, and he’d go back under. He’d swallowed the plug I had on the line way down. There wasn’t no way he could have got loose without he broke the line all the way because he’d done got it down past that tough place in his throat here. If it ever got below there, it’d pull his head off, and he’d still come out of there, or he’d come out dead. He ain’t gonna get that hook out. As long as you’ve just got him up here in the mouth, he can throw ’em out. But I know he swallowed that thing, for I had it hooked right through both his lips, and I knowed he’d have to swallow the whole hook, and sure ’nough, he had.

“I fooled with that ol’ rascal a long time, pulling him in and out. Thedro Wood come up. He had his arm broke, had it in a sling. He said, ‘What’s the matter here?’

“I said, ‘I’m trying to get this big fish outta here. I’ve got a big’un under here. You watch ’im in a minute.’

“Boy! I brought him out of there, and back he’d go. Thedro said, ‘Yea, God! What a fish!’ He said, ‘Next time bring him plumb on out in those bushes. Bring him out on this sandbar, and I’ll catch ’im.’

“I brought him out there, and he went back in. The next time I started with him, I just took right on out through yonder just a-runnin’ with my pole, draggin’ him. Sure enough, he come out on the sandbar, and Thedro fell down on top of him. He said, ‘Come in here. I’ve got it. He’s under me here.’ Says, ‘Just reach under there and get it. He’s under there. I’m on top of it.’

“So I reached around under there, and I finally got to his head and got right up in his gills, and I said, ‘We got ’im now.’ I forgot how long he was, but boys, he was a whopping fish! And no telling how long he’d been in that creek. And everybody had fished by him. I’d been a-fishing by him for over a year before I ever knowed he was in there. Of course, I bet he’d laid right there in that same place.

“I had my pole back in under a bank, just as far back as I could drive it in the bank. I fixed it a purpose, so if he did get on there, I meant to have him. I got a line that I bet would have held fifty pounds and tied on that cane pole! And I wrapped the line way down the pole, so if he broke the end of the pole, I’d still have him down near to the bottom of it.”

Florence Brooks recalled, “I was fishing over there above Lake Burton, right down in the mouth of Timpson Creek. I put my plug out there, and I whipped one. I was bringing it in, and all at once, it got a whole lot heavier. I said, ‘My word, he must be an awful big one!’ He come out, and I saw that a bigger fish had the one I caught in his mouth. I had two hooks on my line, and the other fish was caught by that one. I come out with two of ’em.

“One time when I was fishing up yonder on Burton Lake on a bridge, I saw a pretty hole way up across there, and I just drew back and threw my hook under there. I hooked something, and it broke loose. Since Lawton was fishing above there, I just thought, ‘Doggone it, he’s caught my fish!’ And I swear, I liked to have caught a deer in the nose!

“It was in that water covered up, all but its nose sticking out. I thought it was a rock. When I got it in the nose, it jerked loose and got out of the water and left there. It’s the truth! It tickled Lawton to death. This was last summer. I knew it was a big one, but I wasn’t sure if it was a fish. I told Lawton that if I’d have got him good, he would have jerked me in! I don’t want to catch me another deer!”

Buck Carver explained, “If you ever slip up to a hole and hook a rainbow or a brown, either one, and hook him pretty hard, you might as well forget about that rascal if you lose him, because he ain’t gonna bite again that day.

“One time in my life I caught one over here in Kelly’s Creek. One of the biggest ones I’ve ever caught. It was about sixteen and a half inches long. It was awful broad.

“Anyhow, I was up on the side of the bank, and I dropped my hook in. It had a red worm on it. That fish hit the hook, and I got him about five foot out of the water, and he splashed off and went back in. The hook tore out. I went on up the creek. I was gone about two hours or two hours and a half. I didn’t think he’d bite again that quick, but he took it so fast when I dropped it in there the first time, I figured he must be pretty hungry. I come back down on the other side of the creek where I could get down in the water with that fish. That thing hooked up again. I scrambled around and let him wrestle around over that hole and finally got ’im out. He was about a pound, pound and a half, and there in the roof of his mouth was a big ’ol tore place where I’d hooked him the first time. That was the quickest I’ve ever got one of them durn things to bite again, and know it.”

Minyard Conner informed us, “I’ll tell you a fishing story that happened while I was fishing last summer. We was up yonder at the creek, and there was just so many people, I couldn’t get in. I had on a pair of wading boots, and they had just thrown a stockard in there about twenty inches long—one of them stripers. He was as long as your arm. He’d swim in there, back and forth, and everyone would throw their hook at him. Well, there wasn’t no place for me to stand, so I decided I would wade the river. There was laurel on the other side, and I went over there. That fish had come down and around over there, and everybody was throwing their hooks at him.

“I said to myself, ‘Directly, he’ll come up here, and I’ll snag him.’ He swam up that channel, and I saw him coming. I placed my hook in the water in that channel and gave it a yank and caught him on the right side of the head. He like to have jerked the pole out of my hand. He went round and round, and everyone pulled their hooks out of the water so I didn’t tangle him up with none of them. He just run everywhere, and I guess there must have been over a hundred people standing there fishing. After a while I slung him out and stuck my finger in his mouth and said, ‘Whoopee!’ And it was all over.”

Leonard Jones related, “I used to go fishing, and if I had any luck and come home, my wife, Ethel, would say, ‘Well, did you buy them?’ Well, one time I went and caught one or two cats, real good ones. They’s some fellow there that had four more real good ones. He said he’d take a dollar for ’em. I just give him a dollar and strung them up with mine. Ethel said, ‘Well, where’d you buy ’em at?’

“I said, ‘Every time I catch any you always accuse me of buyin’ them.’ I guess it was two or three years before I told her that I bought them. I wouldn’t tell her. That’s the only ones, though, that I have bought, but she always accused me, if I had good luck, of buying ’em.”

Melvin Taylor reminisced, “We were out in a boat. We were up early in the morning. We saw [a] fish, but there was something wrong with it. I thought at first he had a shad hung in his mouth, but I think his floater was busted. You know, when he runs, he bails that water and takes off. We’d come up on him, and when he saw the boat motor, he would go out of sight and come up way over on the other side of the lake. First thing we’d see was a break of water, so we’d crank up the boat and run on over there. We’d see him dig off again, so we had run him around the lake about thirty minutes or longer, and I told Wesley [my son] if we ever run him into shallow water, we might get him. So we went way on the other side of the lake, and we saw him jump. When we got back over there, he took off again.

“Wesley said, ‘Daddy, I’m glad it’s early in the morning. Ain’t nobody around. They’d think we were drunk or crazy one.’

“We went on over there and sure enough, he went in, broke water, and went out to shallow water. I told Wesley, ‘If we slip up behind him so he can’t see us, we might get him.’ So that time I saw him, his head was at the other direction. I told Wesley to get a net and both hands. ‘Boy! It’s a big one.’ I couldn’t see the fish. I was paddling and Wesley, he was a-looking. He was bent down, had the net in the water. About that time Wesley came falling over backwards in the boat with that fish in the net. Wesley told me, ‘He ran that way, and when he seen the shallow water, he whirled around and run right slap into the net, headfirst!’

“That’s how we caught that one. Wesley said, ‘How are we going to tell how we caught it, Daddy?’

“ ‘Well,’ I said, ‘we’ll just have to tell the truth, son.’

“He said, ‘Ain’t nobody going to believe you.’

“And I said, ‘I know they’re not. We’ll have a lot of fun out of this.’

“So we fished around a while longer, but wasn’t doing no good. We went over to Jack Hunnicutt’s bait place about daylight or a little after, and there were four or five men buying bait. We came in, and they asked us what we caught him on. We told them we caught it on one of Jack Hunnicutt’s smiling night crawlers. They said, ‘Sure ’nough, how did you catch him? What kind of outfit did you have?’

“ ‘To tell the truth, we didn’t have him on no line. We just run him down and caught him in the landing net.’ Boy, they just punched one another and was laughing and going on, you know, and we come on and showed him around. We had more fun out of that, and they rode me and Wesley about that for two or three months. That’s the way we caught that fish.

“Everybody said, ‘Well, that’s not no fun to catch one like that.’

“And I told them, ‘I tell you what. You try running one down with a motorboat and catching him in a landing net. You’ll find out it’s a pretty good sport.’

“That was really an experience. That one weighed eight pounds and ten ounces—that’s a nice one. You don’t get many that size in this country.”

ILLUSTRATION 25 Jake Waldroop

Jake Waldroop recalled, “Yeah, a fish has taken my hook off before. You just have to go out on the bank and tie you on another one and go right back after ’im.

“I was a-fishing up there on Kimsey Creek one time, and I had caught me a big brown trout. He was about sixteen inches long. I got him pulled out and put him on my string, then went on and throwed my bait in. I seen another coming at it, and he struck at the hook. I pulled, and I had him, and I said, ‘That’s the biggest fish I’ve ever caught in my life.’ He just took off right down the river with me, and I just had to let go. He got down in some muddy water, and there was a sandbar there. I finally got him out. I had caught him by his tail. He wasn’t as big as nothing, but he had more power to pull because of where he was caught. The hook had missed his mouth and caught in his tail. That hook is just as sharp as anything that can be made.

“We had a big fish on Kimsey Creek, a big old rainbow. We fished for that fish for three years and never could catch it. One time it rained all night, and the next morning, while we were getting breakfast, a big old crawfish came crawling out the camp door. Al jumped up and got him and put him in a box that we had. He said he was going up the creek and catch that big trout that morning. I had to round up the sows and feed them. While I was down there, I heard Al yell. You never heard such in your life! So I went back to the camp and he said, ‘He got away.’

“I said, ‘No, he didn’t. What’s that you’ve got covered up over there?’ He had him covered up in some leaves. He uncovered him and took him out, and he was twenty-one inches long.

“He said, ‘I put that crawfish on and started up at the head and come down, and I felt him [on my line]. I let him chew on it a little bit until I got him.’

“He had already swallowed that crawfish plus two more and two big chubs about five inches long. He had all that in him when Al caught him. He was a greedy one.

“We played a trick on a man one time. His name was David Rouse. Frank Long and I were up there at our camp, and David came along. He was camping down at another camp, and we told him to go get his stuff and come on up there with us. He said, ‘Do you want to go fishing?’

“We told him we were planning on going. So he said he would be back directly. He came on back in, got supper, and got ready to go. There was an old log laying out in the water. It would go down, then back up, down, then back up. I got my hook caught in it. It looked just like a fish when it went down and up, so we thought we would have some fun out of him. We told him there was a big fish down there at the river that he ought to get out of there. He went and put a number six hook on and went on down to the river. He pulled and pulled trying to get that big fish out. He said, ‘Oh, I got him.’ He pulled ’til the end of his pole broke off. That old man died believing he had a fish at the end of his pole. We never did tell him no better.”

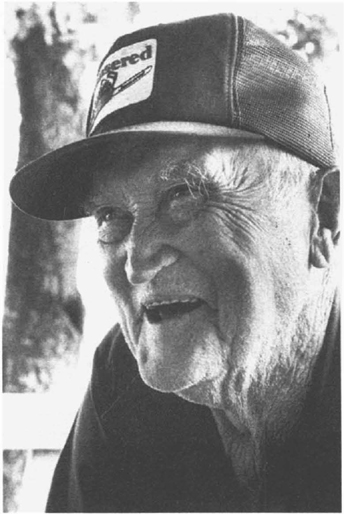

ILLUSTRATION 26 Talmadge York

Talmadge York told us, “A bunch of us, we’d take ol’ man Will Zoellner, and we’d camp. We’d set up at night ’til twelve or one o’clock listening to him tell these big ol’ fish tales. He said he caught ’em so old the fish had moss on their backs back in them streams. Course we believed all that back then.

“It tickled me to watch him eat ’em. He could eat fish! Especially trout. After that, we got to going to these stocked streams. Went to the top of Wildcat one time and caught a bunch of them. He wouldn’t let you cut their heads off. He eats heads and all. He can take a trout eight to ten inches long and start at the head and never spit a bone out. Eats every bone in there. I told him one time, ‘If I eat them bones, it’d choke me to death.’

“He said, ‘When they get about right there [bottom of the trachea], they’re gone.’ And I seen him eat six or eight trout, bones and all.

“Another time, me and Bobby Alexander was fishing. We was wading one side, both of us fishing from one side of the river, and there was fish right next to the bank under the bushes. It was deep out there, and we didn’t want to get in over our heads and get our stuff wet. Bobby reached up to hold on to a bush, and he pulled a hornets’ nest down. He didn’t even see it. That bush with that nest hit right on me. They liked to have stung me to death. I’ll bet there was twenty-five stings right around the back of my neck.

“I went in under the water trying to get ’em off and finally did. We went on up the river, and there was a man and a woman camped up there. She had some alcohol and got me down on the table and fixed my neck up with that alcohol. They liked to have made me sick, so many of them.

“Fish won’t never give up. I got one twenty-three inches long down in Dick’s Creek up in Kay Swafford’s field. I had a fly rod, and I had a lot of line out. I was fishing with worms that day, and I was pulling my line down through there, and he hit it. It was just a small creek, and he went thirty or forty feet. That’s how much line I had out. I just run down the creek with him trying to take up line and finally got him up to the end of my pole. I thought I just run him plumb out on the bank. I started running up that bank, and the end of my fly rod hit the bank and broke it slap in two. I just kept a-running, and I got my fish. He was a nice fish.

“I don’t know of no big fishing tales. One time a bunch of us went over to a little stream in the Glades. The season wasn’t open yet. Me and my wife and Noah Hamby decided to go too. They was going to catch enough out of there for us to cook and eat. We got down in there. Cecil was watching for Bobby to fish, and he had hip boots. The little ol’ stream wasn’t three foot wide, but it was early spring. He had his spinning rod, and he was fishing in there.

“My Jeep was just like the one the game warden had then, and Cecil thought it was the game warden coming in there. He hollered to Bobby that the game warden was a-coming, and he took out right across the hill. His spinner caught in a bush, and he just kept a-going. He run all his line off and broke it, and just kept right on a-going. We drove on down there and kept hollering for him to come back. I guess it was thirty minutes before he come back, scared to death. He had on them hip boots and had a hard time running.

“One time a bunch of us went down to this old mill. Me and Harry walked across the mountain. We went different ways for different parts of the river. We fished down [stream] and didn’t get a strike below Bull Shoulder—way down—and it was just as cloudy as it could be and thundering. It come up a rain, and we waited just a few minutes.

“Then we started fishing back up the river where we had already fished, and everywhere we’d throw that plug, we’d catch a fish. I reckon that rain started ’em a-biting.

“Some of the boys would take us down to the river. Then they’d take the car around, and we’d fish up to them. A lot of times we’d camp, and cook and eat those fish right on the bank. We caught several good trout, brown trout.

“One time down on Licklog, we fished for them little catfish that wouldn’t be but about six inches long. Every once in a while, we’d catch one of them big white suckers. You can’t eat them. You have to throw them back, but you have a lot of fun getting them out. They cut up awful. We caught some of them that weighed two pounds.

“The last few times I went in there and fished that river, it was pretty rough and deep in places. I got to where I couldn’t get over the rocks, couldn’t get my feet up over them. But we had a lot of fun back in those times.”

APPENDIX

Compiled by Doug Adams and Kyle Burrell

THE BASS FAMILIES

Bass are in either the black bass “family” or the white bass family.

BLACK BASS

Black bass is a collective term used to indicate any one of ten large members of the sunfish family. They live in warmer lakes and ponds, as well as warm to cool rivers. All black bass build nests in which the male guards the eggs.

Largemouth Bass (a.k.a. Bigmouth Bass, Black Bass, Bucketmouth Bass, Green Bass, Green Trout). The largemouth bass is one of the most important freshwater game fish in North America. It has dark stripes on its sides, but they disappear as it matures. Young fish have dark lateral bands. Their mouth is large and extends back beyond the eye. Large-mouth bass usually weigh less than ten pounds. It spawns in spring from March through May in waters that are sixty to seventy degrees. Large females can lay up to forty thousand eggs. They eat small fish, worms, insects, crawfish, small turtles, and frogs. They strike artificial lures or live bait.

Redeye Bass (a.k.a. River Trout, River Bass, Shoal Bass). The redeye greatly resembles the smallmouth. It is a small bass found in rivers. Redeye bass are up to fourteen inches long and are very common in the Chattooga River. They eat small fish and crawfish. They can be caught on spinners and lures. Many anglers prize them because they are scrappy, colorful, and highly palatable.

Smallmouth Bass (a.k.a. Bronzeback Bass). The smallmouth bass is considered by many to be our greatest freshwater game fish. The color of smallmouth bass is golden bronze-green or brownish green with distinct faint vertical bars on the side of the body. The mouth extends to the pupil of the eye, but not beyond. There are scales on the base of the fins. Smallmouth bass usually weigh less than six pounds. They prefer deeper, cooler waters and are found in clear streams and lakes. They spawn in the spring in waters that are sixty-five to seventy degrees. They feed on minnows, worms, insects, frogs, crawfish, and hellgrammites. Smallmouth bass will strike artificial lures and live bait.

WHITE BASS

The white bass are the true bass family. White bass are found in rivers, but seem to prefer large lakes with relatively clear water. In the spring, they run up rivers and spawn in running water without building nests where the eggs free-float or settle to a gravel bottom.

Striped Bass (a.k.a. Rockfish). The striped bass is colored greenish or brownish on the upper part of the sides, silvery or brassy below, and white on the belly. Seven or eight dark, well-defined stripes run from the back of the gill cover to the base of the tail. Size ranges of ten to twenty-five pounds are common. Good fishing occurs during the spawning run. The bait commonly used is shad.

White Bass (a.k.a. Striped Bass, Silver Bass). This white bass looks like a striped bass but is much smaller. Sizes range up to four pounds. They swim in schools and are often seen chasing shad on the surface of the lake. They will strike minnow lures and spinners.

THE CARP FAMILY

Carp are large minnows. They are golden in color. The goldfish raised in aquariums and ponds are part of this family. The carp family includes over three hundred American species. They can grow to three feet long and over twenty pounds in weight. They are found in lakes and slow streams. Carp are bottom feeders.

THE CATFISH FAMILY

The catfish family contains over one thousand species. They have smooth, scaleless bodies with long barbels around the mouth. Depending on species, catfish can mature at less than a pound but can grow up to 150 pounds. Most catfish live in quiet waters, but some live in moderately fast-running streams. Catfish are scavengers and will eat other fish, frogs, crawfish, insect larvae, crustaceans, clams.

Blue Catfish (a.k.a. Channel Catfish). The blue catfish color is a rather dark bluish gray on the back, which fades into a lighter slate gray on the sides. It has no dark spots. The average size is two to five pounds. Blue catfish weighing twenty pounds are common, and they can grow to over one hundred pounds.

Brown Bullheads (a.k.a. Bullhead, Mudcat). Brown bullheads are light brownish yellow to black-brown in color and are found in slow or stagnant water. The average size is less than a pound, with large brown bullheads reaching four pounds.

Channel Catfish. Channel catfish are considered the sportiest member of the catfish family. They are colored silvery olive or slate blue with round, black spots. Channel catfish have a deeply forked tail and fairly slender body. They can weigh up to three or four pounds and prefer clear moving water. Most of their feeding is at night. They spawn in the spring with an upstream migration.

THE CRAPPIE FAMILY

Black and White Crappie (a.k.a. Bridge Perch, Calico Bass). The crappie is closely related to sunfish and black bass. The two species, black and white, are very similar. They can grow up to sixteen inches long and can weigh over two pounds. Crappies eat small fish, insects, crustaceans, and worms. Jigs may be used in casting for them. They are easily caught in the spring and make excellent pan fish.

THE PERCH FAMILY

Yellow Perch (a.k.a. Ringed Perch, Yellow Bass). Yellow perch are the best-known perch. They are yellowish, and their sides are distinctly barred. Their fins are tinged with red. The average size is less than a pound. They are found in lakes and are a school fish. Spawning occurs in the spring, and the eggs are laid over sand. They eat insects and small fish. They will strike live minnows and artificial lures.

Walleye (a.k.a. Walleyed Bass, Walleyed Pike). Walleye is a large dark perch. They are becoming less common in local lakes. Walleye weigh up to ten pounds and are also very good to eat,

THE PIKE FAMILY

Northern Pike (a.k.a. Pike). The scaling, which covers the entire cheek but only the upper half of the gill, identifies northern pike. They weigh up to thirty-five pounds and can grow to over four feet long. Northern pike are slender with narrow pointed heads and duckbill-shaped mouths.

Chain Pickerel (a.k.a. Jack, Pickerel, Pike). Chain pickerel are much smaller than northern pike, but look almost identical. They grow to a maximum of three feet in length and also have a duckbill-shaped mouth.

THE SUNFISH FAMILY

Sunfish are smaller than bass, generally about eight inches long. They spawn in the spring. Shallow, saucerlike nests are fanned in the sand and gravel. The male guards the nest. There are hundreds of species.

Bluegill (a.k.a. Bream). Bluegills are small fish about as big as your hand. They can be caught in large numbers in our lakes using crickets, worms, and artificial flies.

Redbreast Sunfish (a.k.a. Bream, Shellcracker, Yellowbreast Sunfish). They are the same size as bluegills and are often found in cool rivers.

Warmouth (a.k.a. Goggle-eye, Redeye, Rock Bass). The warmouth looks similar to a bream but has a larger mouth. They live in lakes and streams and are usually found near shorelines. Maximum length is about eleven inches. They will strike almost any bait and are not good fighters.

THE SUCKER FAMILY (a.k.a. Hog Sucker, Redhorse Sucker, White Sucker)

The sucker is a carplike fish. It is a freshwater fish found in streams, rivers, ponds, and lakes. Suckers spawn in the spring with a definite upstream migration. Their mouth is directed downward rather than forward. They feed on aquatic plants, insects, worms, and mollusks.

THE TROUT FAMILY

Trout are related to salmon but are smaller. Trout are usually found in fresh water. They require clean, cold water to successfully spawn. Wild trout are spawned in the streams. Trout are also raised in hatcheries and are released in suitable fishing waters. The state of Georgia classifies all of the streams in Rabun County as trout streams.

Brook Trout (a.k.a. Brookie, Mountain Trout, Native Trout, Speckled Trout, Speck). Brook trout have light olive-green worm-tracked markings on the upper parts of their body and white on the leading edges of their belly fins. Wild Southern Appalachian brook trout rarely exceed twelve inches in length. Hatchery brook trout can be raised to over sixteen inches in length. Brook trout thrive in water below sixty-five degrees. They spawn in the fall. The female fans a nest with her tail, and when the nest is completed, she spawns with the male. Afterward, she covers the nest with fine gravel. Brook trout eat insects and small fish. The brook trout is actually a member of the char family and is the only trout native to the Southern Appalachians. When they are hatchery-raised, they are called brook trout, and when they are wild, they are called speckled trout.

Brown Trout (a.k.a. German Brown, Speckled Trout). Brown trout are marked with large, lightly bordered red spots. They are brownish in color with a golden yellow belly. Wild brown trout can grow to a length of thirty inches in the Southern Appalachians. They require cold, clean water, especially for spawning. They spawn during the fall in the same way as the brook trout. They eat insects, crawfish, and small fish. The brown trout are native to Europe and were introduced to the Southern Appalachians about a hundred years ago.

Golden Trout. The golden trout, found in some commercial trout ponds in this region, are albino trout. They are the products of a hatchery, and they are not the same as the wild golden trout found in remote areas of the western United States. They are popular in some commercial catch-out ponds because of their unique coloration.

Rainbow Trout (a.k.a. Bow). Rainbow trout have a dark olive back with black spots all over their bodies. They have a broad, red, lateral band extending down the side from the cheek to the tail. Wild rainbow trout in the Southern Appalachian region rarely exceed sixteen inches in length. They spawn from February to April, depending on the water temperature, in the same manner as brook and brown trout. They eat insects and small fish. The rainbow trout is native to the West Coast of North America and was introduced to the Southern Appalachians within the last hundred years.

OTHER FISH

Crawfish (a.k.a. Crawdad, Crayfish). Crawfish are not really a fish, but a crustacean that looks like a miniature lobster. Crawfish make excellent bait for trout, bass, and most game fish.

Eel. An eel is a long slender fish that looks like a snake with a fin on top and bottom. Eels spawn in the ocean and swim up rivers and streams to live. They have sharp teeth, are olive brown in color, and have no scales.

Hornyhead (a.k.a. Knottyhead). This small fish grows up to ten inches long and has little hornlike spikes on its head. This fish is not particularly good to eat and is usually caught by accident when trout fishing. It is the adult member of the chub and minnow families.

Minnows (a.k.a. Dace, Darter, Chub, Shiner, and True Minnow). These are the small fish that live in lakes and streams. They are often used as bait for bass and crappie. They are usually small—less than three inches in length—and are silver in color.

Sculpin (a.k.a. Craw Bottom, Molly Craw Bottom). Sculpin live on the bottom of the creek between rocks and are brown in color. They have a big head and a narrow tail. They are small, with the largest reaching about four inches in length. They make good bait for brown trout.

TURTLES FROM CREEK TO CROCK

“It makes you kind of mad, though, when you go to your hooks and find half of your bait gone and your line twisted up around another bush.”

—Lindsey Moore

We heard of a woman in Clarkesville, Georgia, who had quite a reputation in the area for cooking turtles. Her name was Mrs. Lillie Lovell. We sent a team to meet her, and she agreed to show us how to prepare and cook a turtle—if we would catch one and bring it to her.

After a number of failed attempts at the lake behind our school (the turtles simply stole the bait each time and left a bare hook behind), we were about to give up when Lake Stiles, one of our contacts and good friends, heard of our struggle and caught a live turtle for us! We kept it and fed it until the day of the interview when, with mixed emotions, it was cleaned and eaten.

Mrs. Lovell passed away before the article was completed, so students took the photographs from her interview to Lindsey Moore, a local resident who could tell them what was happening in the photos. He also shared his method of catching, cleaning, and cooking turtles.

—Pat Marcellino and Kenny Crumley