Beer for All Seasons: A Through-the-Year Guide to What to Drink and When to Drink It (2015)

All human life once revolved around the seasons. There was no other way. Nature dominated; our forebears had to adapt or be left behind. Each year was a grand cycle of migrations, fertility, hardship, and renewal. There was prey to be stalked, fruit to be gathered, and gods to appease. Being in tune with the seasons was a matter of life and death for these early people.

As our ancestors came down from the hills and settled into an agricultural existence on the fertile riverbanks, they gained some measure of control, but the new way of life did not diminish the importance of the seasons. Crops had to be timed to the rain and the sun, and the animals they sheltered had their own seasonal patterns. People looked to the heavens for guidance, reciprocating with rituals and offerings to ensure the smooth workings of the cosmos. To this day, religion remains highly connected to the cyclical flow of time and the events it hopes to conjure to fruition. It’s embedded in our spiritual DNA.

During the birth of agricultural life about 10,000 years ago, beer appeared. It is not precisely known what role it played in our own domestication, but having a ready supply of alcohol must have been an irresistible incentive to settle down and abandon the nomadic life. Beyond its obvious charms, beer appears to have been used as an incentive to draw people together for periodic feasts and festivals, building prestige for their hosts and helping to connect widespread communities into tribes and nations through trade, the exchange of ideas, matchmaking, and general merrymaking. It would appear that the beer bash is nearly as old as beer itself. In some ways, beer retains its social power, as is evident during any beer festival today.

A little thirst-quenching was once critical for bringing in the harvest.

As an agricultural product, beer ebbed and flowed with the seasons in well-defined ways. At harvest time, new malt and other ingredients such as hops became available for brewing. Each component of beer has a specific rhythm: cultivation, ripening, harvesting, processing into storage, and its ultimate use in the brew pot. Some ingredients — especially hops — are perishable and start to fade as soon as they are picked, making the first beers of the brewing season something special.

Fast-maturing small beers were enjoyed as summer refreshment.

While the new plants were growing, it was hot, and as a result, summer was never a desirable time for brewing. There was no one available to brew anyway, because most of the available workers were needed in the fields. Summer’s warmth makes it difficult to conduct clean fermentations, and this problem is exacerbated by large amounts of wild microbes wafting through the air. Except for the British Isles, where temperatures were a bit cooler, summer brewing in Europe was often restricted — sometimes by force of law — to weak, fast-maturing small beers intended solely to be enjoyed as summer refreshment and a source of safe, potable water.

For most of Europe, full-strength beers were brewed only in the period between October and March or April, when cooler temperatures encouraged a slow, clean fermentation with a long maturation period for the stronger beers. Such beers were sometimes named for the month of their brewing. In England, “October beer” was the hoppy, amber strong ale most famously brewed on country estates and aged for a year or more before being served. Brewed with little regard for expense from the freshest hops and malt on private estates, it was universally considered the best beer in Britain. After months of small beer, brewers would have been thrilled to get back to the business of brewing real beer, so October beer was quite special. Similar “March beers” were brewed, but these were thought somewhat inferior, as the hops had lost a little of their freshness in the interim.

Germany still brews Märzen beers, most typically associated with Oktoberfest; bières de Mars may be found in France and Belgium. Both are named for the month of March and have their origins in spring-brewed beers that were aged, or lagered, in cool cellars through the summer. Märzen was tapped for harvest festivals and became the beery core of Munich’s Oktoberfest nearly from its beginning in 1810.

These harvest-related specialties were just part of the cycle of beer. Through the depths of winter and well into spring, strong beers came to the table after a long conditioning period. The English term winter warmer sums up these beers perfectly, and in the chilly days before central heating, the term was no mere metaphor.

Much of life in preindustrial Europe revolved around the religious calendar, and some traditional styles reflect this. In Germany, the promise of spring and perhaps the bending of some religious rules surrounding Lenten fasting produced the flesh-sustaining strong lager doppelbock. As spring arrives, we see celebratory Easter beers in northern Europe, followed by the balanced beauty of German maibock. And with or without religion, on that first warm day the picnic tables come out and with them the luminously hazy hefeweizen, Berliner Weisse, or Belgian witbier, as well as other summer beers that will sustain and refresh us until the cycle begins again.

With all these traditions, it’s clear that seasonality in beer was not a whim but a functional necessity, deeply embedded into the social fabric of the day. Technology has empowered us to ignore the reality outside our windows, but it is not that much fun to live our lives totally cocooned. No matter how much “progress” we have made, we still enjoy the cycle of the seasons, as they bring variety and create special moments and seasonal products to look forward to, especially an ever-changing selection of beers to drink.

Mardi Gras has been a drinking occasion for ages.

The Purposes of Beer

Refreshing, sustaining, convivial, and delicious, beer has served many roles almost from the very beginning, sustaining us in many ways — “meat and drink and cloth” as the English put it. Even the ancient Sumerians had small (low-alcohol) everyday beer and medium-strength table beer as well as luxury beers and even a special lower-calorie beer called eb-la, literally meaning “lessens the waist.”

And so it has been for most of beer’s history, right up until modern times, when scale and efficiency dictated that a single type of beer — yellow, fizzy, and easy to drink — would suit everybody’s needs, not just for mowing the lawn but for every other occasion as well. Fortunately, things have changed. There are abundant choices available almost everywhere, and more are coming as the revolution spreads. Craft beer is booming even in places that were quite recently utter beer deserts, so in today’s world you have no excuse for not drinking with the seasons. But at any given moment, what do you really want?

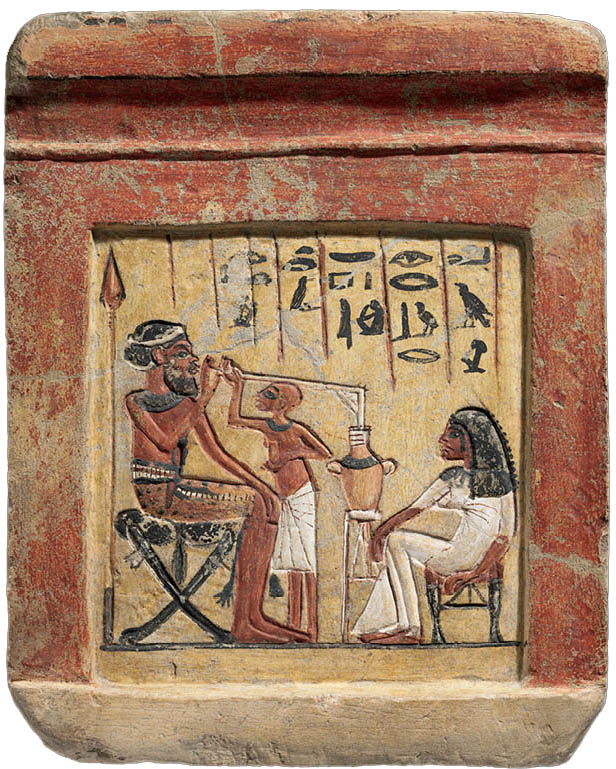

Egyptians offer beer and wine to a Syrian guest. Painted limestone. 18th dynasty, c. 1350 BCE

Outdoor activities in the heat of summer call for light, tangy, and refreshing beers. Despite the surge of strong, bitter beers from many craft brewers, there is a counter trend that focuses on more session-friendly beers to enjoy by the gulp rather than the sip. It takes a little more cleverness to create a delicate, refreshing beer that still delivers a lot of flavor, but it can be done, as anyone who has ever had a beer in England, Germany, Belgium, or the Czech Republic knows. Brewers have tricks for making a modest beer seem more flavorful. Great-quality malts and some fine hop aromas are one way, and that gets you into pilsner, bitter, or Kölsch territory. The rich and creamy, yet dry, character of wheat has long been the basis of many summertime beers, from Bavarian hefeweizen to Belgian witbier and a host of less famous beers that were once beloved throughout the northern regions of continental Europe. A touch of acidity doesn’t hurt, either, as Berliner Weisse demonstrates.

No matter the weather, there is always a need for beers that suit the dining table. These are of middling strength, around 5 or 6 percent alcohol by volume (ABV), and every brewing culture since the dawn of beer has something in this range. Weaker or stronger beers can find food partners, for sure, but in this middle range, beer very graciously interacts with most meals. Given the huge range of flavors and aromas available, there are plenty of opportunities to find connections between beer and whatever is on the plate.

Weighty and carb-rich beers were once commonplace. Often regarded as “liquid bread,” they really did serve that purpose when meat was a luxury and the hard physical work of the day demanded a high caloric intake. Today, strong, rich beers are specialty items; perhaps the term liquid dessert is more appropriate. With our rich daily diet, such beers are counterproductive, so over the past 150 years the general trend has been toward beers that are lighter on the palate and much less weighty.

Drinking with the Rhythm of the Seasons

The you who browses the refrigerated shelves in the heat of summer may be a very different you than the person who stops to pick up something toothsome for the holidays. Every season has its beers, and drinking seasonally helps us stay in touch with the ebb and flow of life and connects us to those who came before us who had similar desires for something refreshing, warming, profound, bracing, or whatever is our heart’s desire. There are hundreds, if not thousands, of great choices waiting to satisfy every beery urge.

Whether you’re actually mowing the lawn or not, the heat of the summer demands beers that are refreshing and not too alcoholic. Most are pale in color, but there are quenching dark beers such as Irish stout and Düsseldorfer altbier, to name two. In the midst of the season’s agricultural bounty, a fruit beer might hit the spot. As the heat of day fades into a glorious summer night, the bracing herbal hoppiness of an IPA could be a great choice, or possibly a hoppy American stout.

As the days shorten and the first chilly breeze of fall blasts through, more substantial beers come to the fore. A rich and malty Märzen the color of turning leaves is iconic for the season. A smoked version of the same might conjure up memories of campfires or burning leaves. Pumpkin ale, with its warm spiciness, is a harbinger of the pies and gingerbread to come as the season deepens.

As the weather becomes cooler and darker by degrees, tastes shift to bigger, darker, more sustaining beers. The holidays demand a certain celebratory spin, and then it’s on to the business of surviving the winter, made possible by a small glass of something strong and dark by the fireplace as the winds howl outside.

Valentine’s Day signifies the promise of new life and gives us a reason for another celebratory moment in a season that really needs as many as it can get. It’s a special opportunity for an elegant and luxurious beer. As the winter ebbs in fits and starts, never warming quickly enough for us, the beers become brighter, paler, more full of hope, until finally there’s that first truly warm day and it’s time to break out something nearly summery, drinking in the fleeting preview of what’s to come.

This cycle of beers ties us to something bigger than our short-lived whims and provides some structure for our explorations. As each new round of seasonal beers pops up in the stores, the beer landscape changes, mirroring the world outside.