Franklin Barbecue: A Meat-Smoking Manifesto (2015)

✵ Chapter One

It’s 2 a.m. on a foggy, cold February night. I have just arrived at work and am looking everywhere for the tamper for the espresso machine. It’s not where it should be, and I’m slightly annoyed. Here at Franklin Barbecue, often the very first thing new kitchen employees are trained to do is pull a good espresso shot. Very important. We have a two-group classic La Marzocco Linea espresso machine taking up good real estate back in the kitchen, and it pulls beautiful shots. Espresso is not on the menu, though, and we don’t serve it to customers. It’s just for us. But it’s what you need when your day starts at 2 a.m.

Having no luck finding the tamper, I improvise and pull the shot anyway using the bottom of a hot sauce bottle. Good enough. Warm espresso cup cradled in my hand, I step outside into the bracing 28°F night. We’re in the middle of one of the massive cold fronts that swoop down through the Midwest from Canada and plunge Austin—and all of Central Texas—into subfreezing weather. This happens several times a year. It can be tricky when it comes to barbecue, as dealing with the changing weather is one of the supreme challenges of cooking good, consistent meat. Weather this cold affects temperatures, cooking times, and the way our smokers draw. But I’ll talk a lot more about that later on.

We have many different shifts at Franklin Barbecue: cooking the ribs, putting the briskets on, meat and sides prep, pulling the briskets off, cutting lunch, and more. The 2 a.m. shift is the rib shift, and I work it a couple of times a week. When I arrive, I say good night to the late-night guy who’s been tending the briskets—which went on yesterday morning around 10 a.m. and were pulled starting around 1 a.m. this morning—and get about my business.

Yes, it’s the middle of the night—but there’s a lot to do before dawn, before another person shows up to work, which won’t be until 6:30 a.m. But first, I spend a moment with my steaming cup of espresso, which I take outside where I’ll tend the fires. I pause to smell that beautiful mingling of crema with the ubiquitous but still sweet smell of the smoke from the multiple oak fires I have going right now.

Here’s what I need to accomplish between now and 9 a.m.: trim and season sixty racks of ribs and get them on the smokers; get the giant cauldron of beans started while warming and breaking up the brisket trimmings from the day before, which will be added to those beans; assess and feed all of the fires we’ve got going; trim and season about twenty giant turkey breasts; constantly keep all of the cookers at about 275°F, taking into account the temperature variations that occur due to the whims of wood fires crackling in freezing cold weather; chat with Melissa, the pie woman, who makes all of our desserts; accept and possibly put away the thousands of pounds of meat—a day’s supply—we’ll receive from the delivery guys at 6:30 a.m. (though, annoyingly, they usually don’t show up on time); carry shovelfuls of coals from the smoker (which we affectionately call Muchacho) to smoker Number Two to start the fires for the turkey breasts and (later) the sausages; get the turkey basting sauce together; check on and moisten the ribs multiple times; pull sixty giant sheets of foil to wrap the ribs; spray, sauce, and wrap the ribs; and get Rusty Shackleford up to temperature for tomorrow’s briskets. Even though it’s the wee hours of the morning and not a single person is around, I often find myself literally running from the kitchen out the back door to check temperatures and load the fires and running back in to handle my duties in the kitchen. Of course, I give myself a short break here or there for an espresso or, in this cold weather, an Americano, which allows for longer sipping. You can balance these coffees on the top of the firebox or on the handles of the heavy smoker doors and let the heat of the cookers keep them warm.

By now, it’s been light for a couple of hours, though I may not have noticed the actual moment the sky changed. Also by now, the line is beginning to form and stretch around the side of the restaurant. On weekdays the first people usually show up by 8 a.m. On Saturdays it can be as early as 6 a.m.

By 9 a.m., I’ve completed most of the duties of my shift. I’m starving by now and can take a brief breather. It’s Austin, so we eat a lot of breakfast tacos. I’ll either put together some brisket breakfast tacos here at the restaurant or head out to Mi Madre’s a mile away for some classic ones. I’ll eat and maybe spend some time answering emails before checking in with my staff, which has been gradually arriving. I’ll go over the day’s pre-orders and consult with the person who’s cutting the meat today (if it’s not me). All kinds of demands will be hitting me now just about running the restaurant. And then, it’s 11 a.m., and the mayhem begins. We open the doors, the line starts moving, and for the next four hours we’ll serve over 1,500 pounds of brisket, all of those sixty racks of ribs, twenty turkey breasts, and 500 to 800 sausage links, not to mention gallons of beans, coleslaw, and iced tea and a lot of beer. I stick around for a good part of the day, putting out fires, checking food, busing tables, and greeting guests, which will be a mix of locals and people from all over the world. Today they waited in the cold, but much more often they may be waiting in the 90°F to 100°F temperatures that we see a lot of around here. They all have in common that they waited anywhere from three to five hours to eat the meat that I’ve been blessed enough to be able to prepare for them.

A DAY IN THE LIFE AT FRANKLIN

12 a.m.

Briskets are pulled off the smoker to rest.

2 a.m.

Espresso! Start prepping for rib shift; trim and rub the beef ribs and build fires.

2 to 3 a.m.

Beef ribs on! Time to trim and rub the pork ribs.

3 to 4 a.m.

Pork ribs on! Continue to watch the fires.

4 to 5 a.m.

Prep turkey; set up mise en place.

5 to 6 a.m.

Turkeys on! Another espresso. Spritz and sauce the ribs; set up warmers.

6 to 7 a.m.

Wrap ribs; set up for line outside; start to rub tomorrow’s briskets.

7 to 8 a.m.

Wrap turkey! Make sides; continue to rub tomorrow’s briskets; start sorting cooked briskets; set up front of house; put up deliveries.

8 to 10 a.m.

Start checking the line; start pulling ribs. Cook sausage. Finish beef ribs and turkeys.

10 to 11 a.m.

Put food on warmers; put tomorrow’s briskets on the smoker; cut any pre-orders.

11 a.m. to 3 p.m.

Lunch! Trim briskets for the next day. Do pork butts; cook potatoes; prep in kitchen; watch fires; dishes.

3 to 6 p.m.

Finish lunch service; clean; continue to trim briskets.

6 p.m. to 12 a.m.

Make sauce; tend briskets; kitchen prep.

Rinse and repeat!

After lunch, I’ll probably run errands around town or have some meetings. Or I might just go home and fall asleep for a while before dinner. Bedtime is usually between 9 and 10 o’clock, before it starts all over again.

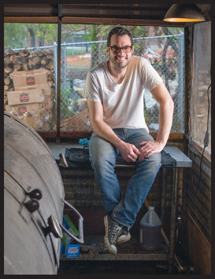

EARLY DAYS

A lot of people might tell their backstory for the sake of storytelling—for the sake of entertainment. And that’s good and valuable in its own right. But when I look back on my barbecue life, I can see that where all this came from is absolutely integral to what it eventually became. What I mean is, I didn’t learn how to cook barbecue just to master a craft. Its evolution in me is a true expression of who I am and where I came from. Specific places, specific times of life and states of mind, and specific people all contributed greatly to what Stacy and I and our restaurant have come to be. You’ll be surprised that when we started we had absolutely nothing—no resources, no knowledge, no image of what we wanted to become. All I had were my own two hands, a work ethic, a positive attitude, a sense of humor, and a fine lady to help it all come together.

Barbecue to me is about more than just the smoke and the meat, more than trying to cook better with more flavor and more consistency (though those things are definitely important). Barbecue is also about a culture that I love. It’s about the smell of smoke and meat browning and the sound of a wood fire crackling. It’s about time, the slow passage of hours. It’s about the people that I hang out with, but also about the solitude of the long, solo cook. For me, it’s about the look and feel and construction of not only smokers but also of buildings, cars, guitars, and other beautiful, artfully designed things. It’s about service and about people relaxing and having a good time. It’s about the connection I feel to a vast, time-honored cooking tradition and to all of the people practicing it across Texas and across the country every single day.

✵ ✵ ✵

In 1996, when I moved to Austin from Bryan-College Station, Texas (100 miles northeast of Austin), it was never my intention to open a barbecue restaurant. In fact, I wasn’t even into barbecue. I was nineteen years old and into rock ’n’ roll. Barbecue wasn’t something I even really thought about much.

It’s true that when I was little, around eleven years old, my parents did own a barbecue joint in Bryan for a while. It was a cool old place with a classic brick pit from the 1920s, a fire on the floor (in barbecue, pit is an interchangeable term for smoker or cooker and may be an actual pit or might be something that stands on legs or wheels aboveground)—the kind of joint that just reeks of character (and that you can still find in small towns across Texas).

It did make an impression on me, but not necessarily on how I cook. Rather, it just sank into my psyche and came to kind of nestle there, associating barbecue for me with the good things in life—with family and friends and that certain sense of well-being that you have when you’re a kid in a good place. Even though it didn’t really occur to me until long after, I think the sense of nostalgia that I carry from my parents’ restaurant sits at the heart of the passion for barbecue that I later found in myself.

But equally important was the music store that my grandparents owned. I spent a lot of time there and worked there throughout my teenage years. I did a little bit of everything—selling instruments, setting up PA systems, giving guitar lessons, repairing guitars and amps. I developed my passion for music there but also for something else: for taking things apart and fixing them—for tinkering, for disassembling objects and seeing firsthand how they work.

You might not think that that approach to things has much application to preparing great barbecue, but it does. Understanding how things are put together and how they work is the first step toward improving them. The more you do it, the better you get at it, and if you don’t have any fear of getting a little dirty or of prying something open and examining how it functions, you start to develop the confidence that you can fix most anything and even make it run better than it did before. And that’s basically the approach I’ve taken my whole barbecue career and am still taking today, working daily to improve my smokers and my restaurant in general to make it more efficient, more consistent, and more durable.

But back then, after I graduated from high school, all I wanted to do was play music. So I went to Austin and had a good time working odd jobs and playing in a couple of bands. We’d play rock shows, go on tours in vans, that kind of thing—24-inch kick drums, Marshall stacks, fists in the air, Pabst Blue Ribbon. I realize now that even playing music fed into my later endeavors. It may not seem like it, but there are many similarities between playing in a band at a show and putting on a barbecue.

✵ ✵ ✵

My love of barbecue—my insane obsession with it—started to crop up about the same time I met Stacy, now my wife and collaborator (enabler?) in everything. It is a good thing she’s patient and accepting of me because she had to tolerate a lot of barbecue talk for a long time. I’m not sure where barbecue came from exactly. It’s not like it all just hit me one day. No, it was more like the way winter turns to spring slowly until one day you look up and it’s green everywhere. That’s how barbecue started for me, as just a little interest, before it became a full-on infatuation and ultimately, unpredictably, my life.

The whole thing really started rolling when we got our first little cooker, a New Braunfels Hondo Classic smoker, for $99 from Academy, an outdoors and recreation store here in Austin. It’s a classic offset smoker in the Texas style, with a firebox that connects to a cooking chamber on one end and a smokestack on the other. It’s so cheap because it’s made economically and with very thin, inexpensive metal that’s not designed to last or even hold heat or smoke very well. Why did I get it? I went out to get a grill for our first place together, but I bought a smoker instead. I guess if you live in Texas long enough, barbecue starts to penetrate your consciousness. And when you get that hankering, you get a smoker, and this was what was available to me at the time.

I have a love of design and architecture overall, but especially of a certain roadside style of Americana from the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s, which in my mind is really represented in barbecue culture. In 2003, Texas Monthly, our state magazine, released its second full issue devoted to barbecue (the first came out long before, in 1997), and that’s when things started to hit home for me. The first time I saw Wyatt McSpadden’s photos of these great old barbecue temples in Central Texas towns, I thought, Wow, that is so cool! I’d never been to the places Wyatt was shooting, but his photos made me think of my parents’ place back when I was a little kid, and I realized that barbecue just triggered all sorts of great feelings.

Now I realize that it was about more than just the meat; it was about the character and resonance of barbecue culture. You don’t go to those places just for the meat. To walk past the open fires into the smoke-blackened halls of Smitty’s in Lockhart is practically a religious experience. You wouldn’t want to eat barbecue—even if it was the greatest in the world—at a restaurant that felt like some sterile white box. It wouldn’t taste the same without the visuals, the smells, the smoke on the walls, the memorabilia, the pit guy lifting up the smoker lid and a plume of smoke coming out.

My relationship with Stacy was one of the main reasons I gave up the touring musician lifestyle. She supported all of my obsessions—music, carpentry, and, eventually, barbecue—but the band would go out on these tours, and I’d find that I just missed her and missed being home. I thought maybe I should just come home and get a job, but that’s also when barbecue started to become a persistent presence in my mind. Stacy is from Texas too (Amarillo, way up in the Panhandle, to be exact). She wasn’t as in love with barbecue as I was, but like me she enjoyed throwing parties and was always game to put on a cookout together. Believe it or not, a series of casual cookouts ended up being my only real training before we opened the trailer that would eventually turn into our restaurant. So each one of those backyard parties with friends remains pretty vivid in my mind, especially as they were often tied to a particular residence we had at the time. Austin is full of funky neighborhoods and funky old rent houses, and we moved around a lot.

I cooked my very first brisket in 2002 at one of those backyard cookouts. (For those of you who are keeping track, we opened the Franklin Barbecue trailer in 2009, which means, yes, I had been cooking brisket for only seven years when we first started.) At the time we lived in a little three-plex. My band had done an in-store performance at a record shop, and we had maybe a third of a keg of Lone Star left over. So I told everyone, “Hey, I’m cooking a brisket. If anybody wants to come over tomorrow, we’ll finish off this keg and eat it.”

I had just gotten my New Braunfels cooker, and this would be my maiden voyage with any kind of smoker. It could hold two briskets, if they were stuffed in there, with each brisket capable of serving maybe ten people. I picked up the brisket on sale at H-E-B—our big chain of Texas grocery stores—for $0.99 a pound. It was prefrozen, commodity, probably Select-grade meat. And I had no idea what to do with it because I’d never cooked anything on an offset cooker. In fact, I’d never shown any particular aptitude for cooking with fire. Negative talent, probably. So, I went online to try to figure out how to make a brisket. Let’s just say the Web in 2002 was not as robust as it is today. I called my dad and asked him how to smoke a brisket, and he said something vague like “Just cook it until it’s done.”

About fifteen of us—the band and some friends—convened the next day. My brisket was flavorless—tough and dry—but everyone was terribly nice about it. They all said it was good. Maybe they really thought that, but I knew it was not true. In hindsight, I didn’t wrap it, and I pulled it off right when it was at 165°F internal temperature, smack in the middle of the stall. (We’ll talk much more about that later, but at the time I didn’t even know what that was.) That was my first brisket: $0.99 a pound on a cheap cooker I’d bought for $99.

Shortly after, Stacy and I moved to Bryan-College Station with the plan to save some money and eventually move to Philadelphia, a city I adore, for a while. Only, we were so miserable to be back in a small town that we found ourselves driving to Austin all the time for work, to be with our friends, and to play music. But it was in Bryan that I did my second cook.

We had a small two-bedroom wood-frame house from the 1950s. It had a pretty nice little backyard. So we had a few people over on a Sunday, just like everyone does. I was itching pretty badly to smoke another brisket, which, again, I purchased on sale for an incredibly low price, and I cooked it on the same little cooker. I still didn’t know what I was doing, but I do believe this one turned out slightly better.

I also decided to take things to the next level by making a bunch of barbecue sauces. As a test, I also bought a bunch of crappy commercial ones. We composed a grid and asked everyone to pick their favorite sauces and to offer some tasting notes. I didn’t realize it at the time, but I was clearly behaving in a way that suggested I might think of doing this in some kind of official capacity. The sauce test was pretty much the moment when I learned to stop asking for opinions and to listen to my own judgment. People chose the worst ones as their favorites. I believe Kraft actually won. The few commercial ones that I really liked didn’t place very high, while the couple I made from scratch placed somewhere in the middle. As it was, our experiment of living in Bryan to save money didn’t last long. We missed our friends and our lives in Austin and were spending lots of our time there anyway. Ultimately, we gave up the Philly idea and decided to head back to Austin, where our futures clearly lay.

✵ ✵ ✵

Still, Stacy and I were incredibly poor, and when I say poor, I mean well below the poverty line. The kind of poor where you’re writing your rent check before you get your paycheck and just hoping it works out. After your paycheck goes through, you realize you have $8 to last you a week before you get your next one. I remember going down to H-E-B to cash in a jar full of change so I could go out and buy a little barbecue.

But we weren’t terribly stressed about this. Austin was like that back then. It was a good time and a simpler one. You could pass on jobs to friends, just as you could houses or apartments. You could live cheaply off minimum wage and tips. It was a city full of people like me—people not doing the stereotypical thing of going to college just to get out and find a job, but trying to figure out and do something they really enjoy, like playing music for not much money. People like to say that Austin was a town full of slackers, and I guess on the surface I could have fallen under that category. But I was never a slack worker. I’ve always had various jobs and always worked hard. I just can’t easily work for other people or do work that I don’t care for.

Stacy had a job—she waited tables. She was the breadwinner for years, though I always had something I was doing, something to bring in some money. For years, I did random stuff—more often than not, I worked for free on projects for friends. Someone would ask me for help, and I’d think, Well, I don’t have a job right now, so, sure, I’ll help you build that. There were times when Stacy was definitely frustrated with me.

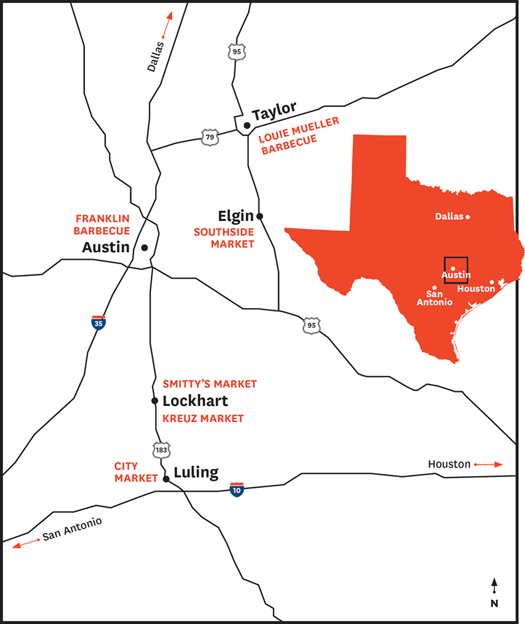

And, yes, in those years, my interest in barbecue was still percolating—it was kind of a constant buzz in the back of my mind. I did a small tour with my friend Big Jeff Keyton, a terrific local musician, and his band, and on those long drives we realized that both of us were really into barbecue. So he started taking me out on occasional day trips to visit local barbecue joints—heading 30 miles south down to Lockhart for Smitty’s and Kreuz, or 20 miles farther to Luling’s City Market, and especially 40 miles northeast to Taylor to the great Louie Mueller. I’d save and save to scrounge together a few bucks just to be able to go out and taste some barbecue.

I remember that first morsel at Louie Mueller. The place has great counter service—really nice and friendly—and the staff traditionally cuts customers a little taste of beef when they get through the line and up to the counter to order. When I got to the front of the line, Bobby Mueller gave me one bite that turned out to be a whole end cut. I don’t know why he gave me that gigantic piece. My eyes must have been bulging, and I might have cried a little bit, but it was so, so good. Sooooooo good! And it started to change me.

It was maybe another year before my next cook, in 2004. This cook signaled another small step in my development, as I prepared the sides as well as the meat, and learned I could put it all together myself. A friend wanted to have a party and said, “Hey, I’ll buy the briskets if you want to cook them.”

I said, “Hell yeah,” because any chance I could get to learn how to cook these things was a boon. And so I cooked the briskets in the front yard of our house and took them to his house while they were resting. And I remember that was the first time people recognized me and said, “Man, that’s Aaron, the barbecue guy.”

For that party, I had saved up my money and bought a $20 knife. Friggin’ sad. I saved up $20! But it’s true. I had gone to Ace Mart and bought a cheap Dexter-Russell knife. Still have it. It’s at the restaurant, though we don’t use it anymore. It just goes to show that you don’t need fancy equipment to do most any task in barbecue.

Our next residence was an incredibly dumpy house. There was no real backyard, as the house was on a quarter lot and it took up almost the whole property. It was a one-bedroom, 480-square-foot house, probably around $500 a month in rent. We had one barbecue while we lived there. That was the fifth cook, and the year was 2005.

I had played a show somewhere that night, packed up my drums and left the show early, and got back to the house feeling very gung-ho. The prospect of cooking a brisket was just the most exhilarating thing. Months had gone by, with me trying to scrape together enough cash to put this one puny barbecue on. And, man, I was so excited. I remember firing up that little New Braunfels cooker. I had bought two briskets from H-E-B on sale for $0.99 a pound. I recall feeling like a badass walking out of H-E-B with a shopping cart filled with a whopping two briskets.

I got home from that show probably around 2:30 a.m. I remember just sitting in this small hammock in our tiny, 10-foot-wide backyard, getting the fire going. Our place was at a four-way stop, and there was this streetlamp that would cast its light down into our yard. I just stared at it, thinking it was the coolest thing to see that smoke start wafting up into the night. I was so stoked.

I dozed outside on the hammock while tending the fire. By the next morning, things were going smoothly. I’d pulled the briskets and we were getting the yard ready. Just when it all seemed perfect and twenty to thirty people were about to show up, go figure, the plumbing backed up. A root had cracked a pipe from the toilet, and there was sewage floating up into the yard. Gross! The owner of the house was in prison, so we couldn’t really call anyone. And I had bought all of this food with what was, as usual, my last few dollars, so we couldn’t call it off. It was a Sunday, and I remember finding a piece of plywood and just covering up the swamp. Stacy and I were looking at each other saying, Oh my God, oh my God, oh my God. The bathroom doesn’t work. This is terrible!

But, somehow, no one noticed, except that we couldn’t use the house’s one bathroom. I remember not being really happy with the brisket. For one thing, I may not have realized that cooking two briskets at the same time would alter the process. But I might have also been disappointed that I wasn’t improving by leaps and bounds every time I managed to cook a brisket. Now I know that progress doesn’t always flow in a steady stream. You have to give yourself some slack, because learning how to make barbecue takes time, and not everything’s going to be a big success.

Not that this was by any means a failure. The brisket just wasn’t appreciably better than what I’d done the last time. (Of course, what do you expect when you take months and months off in between cooks?) And I didn’t know if my sauce would come out really bad, so I bought a gallon of some really crappy stuff that I could doctor up just in case my own efforts were inedible. But my sauce was fine, and everyone seemed to have a great time. The next day I fixed the pipe. We got out of that house pretty darn quick.

✵ ✵ ✵

I was still working various jobs that didn’t pay too well. I worked at a van place, fitting out and customizing vans. I worked in various restaurants. But there were two jobs that ended up having the greatest impact on me: at a coffee shop called Little City, where I worked in the back making sandwiches and doing maintenance, and where I started developing my love of coffee; and the Austin barbecue joint of John Mueller, grandson of the legendary Louie Mueller.

Somewhere around that fifth cook—yes, the one with the septic disaster—I caught myself daydreaming about opening my own barbecue place. (Of course, now that I have my own restaurant, bathroom disasters are an ever-looming threat!) I’d hardly ever been that excited about anything other than music. So I started applying to a bunch of Austin barbecue joints, some of them several times. I wanted to work at a place that barbecued with a real fire, not gas ovens, and there weren’t many of these in Austin at the time. I wanted to learn barbecue from the inside out; I want to live it.

I got the job at Mueller and worked a lot, even though I was making only $6 or so an hour. I was constantly observing and soaking up whatever lessons I could. (I should interrupt myself here and offer a little backstory for anyone who doesn’t know John Mueller. Here is how Texas Monthly describes him: “If there’s a dark prince of Texas barbecue, it’s probably John Mueller, the famously irascible, hugely talented, at times erratic master of meat who left his family’s legendary joint—Louie Mueller Barbecue, in Taylor—and set out on his own in 2001.” That place is the one I worked at. It developed a big following, but for various reasons he closed it in 2006 and disappeared from the scene for a while. He opened a new place in 2011 with his sister, but a fallout there led to him departing again. Now he has his own place once more. He and I appeared on the cover of Texas Monthly together in 2012.) When I worked at John Mueller’s, I didn’t cook anything. But I got good at chopping cabbage and onions. I could cut 50 pounds of onions without shedding a tear. I started rubbing briskets in the afternoons and watched how John handled the meats. I ended up getting to cut the brisket for the customers, which turned out to be a valuable skill. Often at night, the owner would leave, and I would just be left there on my own, which was great. People would come in, and I’d greet them warmly, take their order, and cut their meat for them. At those times, I would sort of treat that place with care and a friendly spirit as if it were my own. That kind of amiable, hospitable spirit is important, something that we’ve always emphasized at Franklin Barbecue.

It helped that I love cutting brisket, and I love talking to people. To this day, people who used to eat at that defunct restaurant still come into Franklin every now and then and remember me from when I was working behind the counter. Even more than I care to admit, that short-term job probably led to much of what I do now. But it wasn’t because I received any mentoring. It was because I found myself doing something I really loved. Eventually, when I could see that writing on the wall that its days were numbered, I quit.

✵ ✵ ✵

LEGENDARY CENTRAL TEXAS BARBECUE

Before I ever cooked a brisket, I was taking day trips out to visit the various pillars of Central Texas barbecue. In those days, there wasn’t really any good barbecue in Austin; it all lived in the small towns outside of the city in every direction. There are barbecue joints everywhere in Central Texas, but there have always been a few places that have stood above the rest. It’s worthwhile to visit these temples because in their old buildings and time-honored ways, they provide a window into barbecue history, not to mention a taste. These days quality can be up and down, but they all do something really well, and when they’re on, the food can be as good as it gets.

SMITTY’S MARKET, LOCKHART ✵ Just 30 miles southeast of Austin, Lockhart is a historic barbecue town, and Smitty’s is a glorious living relic of the way things used to be. The building itself is a must-see place that all barbecue fans should visit. You enter through the back and walk right past a roaring fire literally at your feet, even if it’s 100°F outside. ✵ FAVE DISH: the best sausage!

KREUZ MARKET, LOCKHART ✵ Just down the street from Smitty’s is the massive redbrick food hall known as Kreuz. Smitty’s used to be called Kreuz, but due to a familial disagreement, one sibling took the name while the other kept the original building. So here you have a new building, but with the original name and techniques. Mutton-chopped, soft-spoken Roy Perez is the pitmaster and a barbecue celebrity. It’s always heartening to stop in and see him tending his pits. No forks or sauce here, following the old ways. Lots of good food is on offer, but the true specialties are the smoked-to-perfection pork chop and the snappy, spicy sausage links. ✵ FAVE DISHES: end-cut prime rib, pork chop, jalapeño-cheese sausage.

CITY MARKET, LULING ✵ Luling is a little town 15 miles past Lockhart and is home to yet another Central Texas barbecue great: City Market. Under the pitmastership (yes, I just coined that term) of hard hat-sporting Joe Capello, City Market is one cool spot. You enter a little smoke-filled room in the back of the restaurant where the meat is cut. Then you step back out into the dining room to find a table. There’s great people-watching at City Market, and the sausage and ribs are great! ✵ FAVE DISHES: sausage, crackers, cheddar cheese, great sauce.

LOUIE MUELLER BARBECUE, TAYLOR ✵ An hour to Austin’s northeast is the little town of Taylor, which is probably most famous for the epic Louie Mueller Barbecue. Founded as a grocery store in 1946, with barbecue coming a few years later, the building itself is a beautiful shrine, with smoke-blackened walls and heavenly light streaming in through the fog. The food here has had its ups and downs over the years, but when it’s good, there’s almost nothing better. And it’s been on a hot streak for a while. While the dipping sauce is sort of thin and watery, the meat’s so good it doesn’t need it, led by super-peppery brisket and a beef rib that will blow you away. Do not miss this place. ✵ FAVE DISH: beef rib.

SOUTHSIDE MARKET, ELGIN ✵ Elgin is the sausage capital of Central Texas in large part because of the Southside Market. Started in 1882, this place oozes amazing tradition, much in the same way its famous Hot Guts sausages ooze deliciously meaty juices. In the past Hot Guts were spicier than they are today, but they’re still darn good. Just a 30 minute drive from downtown Austin, this place is always worth a visit. ✵ FAVE DISH: sausage, obviously.

It was now 2007, and I had it in my head that I wanted just a lazy little lunchtime spot that I could design, decorate, and cook for on my own. I was trying as hard as I could to figure out some way to get my hands on or make a cooker that was big enough to cook multiple briskets. I had a dream but no real idea of how to get there except for sheer desire.

More and more, I saw entertaining as practicing for the big time when I would have my own place. I’d be calculating in my head, This is the time I’d put the meat on; this is the amount of time I’d have to make the sides. I knew I wanted my restaurant to be as authentic and old-school as possible, with a personal touch—I’ll never cut the brisket in advance and put it out for people to pick at. I’m going to slice each and every piece individually for each customer because that is how it’s done.

Looking back on it now, I know I probably seemed naïve. And I was. But I’m also proud that we made it happen with just ourselves and the help of our friends and family. Sure, I was poor. But barbecue has never been a rich man’s pleasure. It’s always been a culture of thrift. It’s a poor, rural cuisine based on the leanest, throwaway cuts of the animal being cooked until edible with a fuel that can be picked up off the ground (at least it used to be).

And that’s what I loved about it. How many other things can you start from nothing? There aren’t a lot. In barbecue, you sell something that you bought and prepared on the same day, which gives you a little bit of positive cash flow to buy the next day’s raw ingredients. You add value to the ingredients through cooking, and then do it all over again. That’s how this entire thing has happened and is in fact still happening. This restaurant has not accrued one cent of debt. And that’s because you can build something out of nothing if you’re just willing to work at it.

And that’s where all of this isn’t that different from playing in a rock ’n’ roll band. I didn’t know it at the time, but it’s all kind of the same. You get in a van, you hit the road, and you play and play and play as much as you can to get better and earn a little money. That’s punk rock. That’s DIY. That’s the spirit. You make something with your own two hands. I run the restaurant the same way I’d run a band. It’s the same thing, just a different venue.

ALMOST THERE

When it came time to rent a new house, I definitely, without question, had cookouts on the brain. So we went with a place with a huge backyard, almost a third of an acre. I was looking at this backyard and seeing barbecues. Like a party house. It was still inexpensive, but it was a step up.

Our next cook was on the Fourth of July. We’d always had barbecues on Sundays because Stacy and I worked on Saturday nights. That meant I’d be out pretty much all night on Saturday, get home at 2 a.m., and start cooking for the next day. People would come at 5 p.m. the following evening, and we’d start serving at 7 p.m. But we scheduled this Fourth of July barbecue for a Saturday instead of a Sunday because of the holiday weekend. What a mistake. People drink a lot more on Saturdays and stay too late. Still, I was feeling good about the brisket; it was definitely improving from one cook to the next. Lesson learned: don’t have barbecues on a Saturday night, because you’re just asking for trouble.

I still had the one, original New Braunfels (which, by the way, is still around; I loaned it to a friend with the instruction that he could never get rid of it without asking me, as it’s a sentimental piece with serious mojo, even though it’s just a crappy little cooker that’s probably rusted out on the bottom by now). But after we had gotten rid of the last guests—wiping the sweat off our brows and feeling lucky that we’d dodged a bullet at this rowdy party—I went online. We had dial-up Internet on one of those old clear iMac computers. Pretty much every day I looked on Craigslist under the searches “Free” and “BBQ.” I’d check the Free section for anything that I could possibly use to make a smoker: old refrigerators, old water tanks, an old oven that was getting thrown away. I even tried to figure out a way to turn an old bathtub into a smoker (real classy!). Anything of substance that was free and I thought might come in handy, I considered.

That night I typed in “BBQ.” To my surprise, as it had never happened before, a listing for a cooker came up, the second or third item in the list. The ad said something that amounted to “free smoker, used twice, stinks at bbq, come get this piece of junk.”

And I went out of my head. I yelled to Stacy, “Oh my God, I’ve got to go get this thing! Somebody’s probably already got it!” I ran to the truck. It was late at night. As I drove I could imagine the scenario: someone had a disastrous experience cooking some meat earlier that day, got so frustrated that they wheeled it out to the driveway, went inside and put the thing up on Craigslist that very night, and swore to themselves that they’d never do it again.

I’ve hardly been that excited about anything in my whole life. Thoughts raced in my head as I drove: Must get there as fast as possible. It’s heavy, how will I get it in the truck? I don’t care, I’ll push it home if I have to. How could somebody put something that valuable ($100) on the street? What if somebody’s already grabbed it?!

I remember turning onto the corner, heart pounding. Then I saw something—just a little black dot at the end of the street. It’s getting bigger, it’s getting bigger, and there it was. I probably started sobbing in the truck. I rolled up, turned off my headlights so as not to disturb the neighborhood, and took a look at the smoker. A New Braunfels Hondo. Oh my God, it’s just like the one I have! I can double my capacity! Now I’ll have two really crappy cookers that aren’t worth anything. But I can do four—count them, four—briskets. That doubles my capacity and thus the number of people I can feed. I had certainly come to realize that cooking briskets on these things was hard because of their thin, heat-leaking construction and other inefficiencies. Later I’d have the opportunity to transcend those ills with better cookers. So I wheeled the thing into the street. It rattled loudly, like a shopping cart on a cracked parking lot, and I loaded it up myself. It was heavy, and a full-size truck is pretty high up there. But I got it in and drove off with what until then was my greatest-ever find.

✵ ✵ ✵

Something changed in me when I got that second smoker—something clicked, and I started to feel as if maybe owning my own place wasn’t so crazy or far-fetched after all. So I decided to start saving up some money in earnest. I was doing good, making about $11 in tips a day at Little City. Stacy worked every Friday night waiting tables. At that time, on Fridays I’d spend the money I’d saved up all week at Half Price Books, just a few dollars on whatever cool cookbooks I could find, as well as books on architecture, anything barbecue of course, roadside stuff—especially Route 66 Americana—1950s design, and old diners. I was gathering information and inspiration like so many nuts packed into a squirrel’s cheeks.

After procuring the new smoker, we had our next Sunday-night cook. I think we hosted seventy-five people or so, and to accommodate them all, we collected tables and chairs from Craigslist that we mixed and matched out in the yard (thank you, Free) and strung Christmas lights overhead. I moved an old, cheesy 1960s-style bar from our living room outside and set it up to cut brisket on. I borrowed a friend’s little tiny cooker to add to my two and did a record five briskets that night. The food turned out pretty good, and it was one of the most fun barbecues we ever had—and the first one where something novel happened that also helped me along the way. There I was, drinking, cutting brisket in the dark. It was kind of like a block party, way bigger than we thought it was going to be. A line of hungry people extended around the yard, and we ran out of food. Little did we know that we were really ramping up here. Big party, lots of food, major service operation. I had designed a little service area just as I’d do it in a restaurant, really paying attention to mise en place, ergonomics, and flow. And the meat seemed to be getting a little better. I was learning how to cook multiple briskets at the same time, learning that each one required its own attention and own program. The idea that so much of this was about attention to detail was really becoming a massive part of the way I looked at barbecue.

Toward the end of that night, Big Jeff, my great friend who’s been a part of my barbecue journey since close to the beginning, came up and said, “Hey, I got this for you,” and handed me a manila envelope. In it was a roll of ones, fives, and maybe some tens.

“What’s this?”

“I took donations for you tonight,” he said, taking a slug of whiskey. “You need it.”

I didn’t know he’d been asking people for money, and I got a little choked up because it was the most thoughtful thing. Throwing that cook probably cost us the equivalent of our rent. The money he raised might not have completely covered our expenses, but it helped a lot. I just couldn’t believe it, because I’d worked so hard and had so much fun and then at the end of the night I got paid, which I never expected. It was like playing the best show of your life and then getting paid and realizing the venue gave you some extra and thinking, Man, we can stay in a hotel tonight!

I shut the bedroom door and sat on the bed and counted the money and thought to myself, Wow, maybe I can do this. And that was the first time it ever truly seemed real to me.

THE FINAL PIECE

I was really conquering something that had felt unattainable. It must be like when people finally run their first marathon. I was on cloud nine by the end of that last cook. This was the first time we had a barbecue where I cut everything to order and had a stack of plates on the table and could ask people if they wanted lean or fatty, just like at a real restaurant. This is what I still do every day when I cut lunch. I honestly believe that one of the reasons our restaurant is successful is because we take the time to talk to people, to get to know them and what they want to eat—same as if we were hosting them in our own backyard.

Not long after that fifth cook, in 2006, I volunteered to remodel a house for the brother-in-law of my best friend, Benji (who today is an essential part of the restaurant—Benji is the GM, “the Dude”). I’d never remodeled a house in my life, never even really worked on a house. I was just kind of handy with tools, and I’d done some maintenance. On restaurants. Nevertheless, I knew I could figure it out, and I worked on that house day and night.

My final pay was maybe around $6,000 and change. When I deposited it, the bank probably thought I was doing something illegal, because my account had never seen more than $300. It was the most money I’d ever had in my entire life. What did I do with it? I bought a barbecue pit (what we call a smoker in Texas), the one that is today known simply as Number One. How I got it is yet another story of luck, thrift, and perseverance.

I invested $5,000 of the money I’d made into a new house that Benji bought and where Stacy and I would be living with him. That left $1,000 or so for my next big purchase.

Number One was the very same smoker that John Mueller was cooking on when I worked for him. It was made from a 500-gallon tank procured from the side of the highway (to put that in perspective, my New Braunfels smoker had a capacity of maybe thirty gallons. As I saw coming, Mueller’s restaurant had failed, and Stacy’s old boss had taken over the space and gotten the smoker.

When I found out they had it, I asked them if they wanted to sell it. They said they were going to but mentioned that they thought it was worth about $5,000. No way, I thought, no way. I told them I thought it was worth about $1,000. Obviously we were far from a deal, but they said they’d get in touch when they were ready to part with it.

That cooker never left my mind, but I went on working my various jobs, doing my thing. And one day, as was my habit, I was searching Craigslist and saw a listing for a cooker. It was the same one. So I connected with the guys and they said, “Sorry, we forgot to call you.”

That thing was in terrible condition, but they were holding their price. I countered that it was way too much, as I’d seen it in action a year previously and it was just an ordinary smoker with many flaws. Again, no deal, but I said that if no one bought it, I’d take it.

They called back a little later and agreed to sell it to me for my offer of $1,000. And I thought, Oh my God, another one! I was dancing around like a new contestant on The Price Is Right, because the price was right. I said, “I’ll be there in five minutes,” cash in hand.

This thing was huge—14 feet long, solid metal, mounted on a trailer you could pull with a truck. I figured I could put twelve briskets in there—enough to serve more than a hundred people. After all, that’s all Mueller cooked with for that whole restaurant.

It didn’t look anything like it does now. It had three little doors; a real crappy axle; a solid piece of pipe, probably 3 inches in diameter; two plates to make a cradle for the smoke chamber to sit on; a 500-gallon tank; and then other plates with spindles welded onto them for the legs and tires. It had one flat tire, and its other tire was from a car. In chapter two I’ll explain all of the things that make a good smoker good and what I look for in all of the smokers I buy or build. But for now, suffice it to say, when I bought it, Number One needed some work.

When I got it home, I saw what a disaster it really was. Inside, undrained grease had accumulated all of the way up to the grate, about 18 inches deep. There were still crusts of burned meat stuck to the grates. The thing hadn’t been touched in well over a year, and it stank. Opening the firebox, I found it was almost completely full of ash that had hardened and become as tough as concrete. (At the restaurant we clean out the firebox constantly.) It never had a grease drain on it, so the grease oozed into the firebox, which by then had piled up layers of ash, coals, wood chunks, and then a steady trickle of animal fat. It was all rancid and hardened, like sedimentary rock with little pockets of fossil fuels dripping out.

So I went to Home Depot and bought a cheap grinder with a wire wheel (a brush with bristles for removing corrosion and gunk), a grinding disk (for grinding through metal and rust), a rock hammer (for chipping stone), and a $3 pair of goggles. Then I started the excavation, Shawshanking my way through that whole firebox, which is about 40 inches long. It’s got this little back door, and eventually I crawled inside the cooker like a miner to access the back end. Chipping away at this ashy concrete, I would encounter disgusting little pockets of rancid fat. Every day for a couple of weeks, I’d grit my teeth and force myself to go back in there. It was gross, but where else would I get a huge cooker for $1,000?

Finally I got it all cleaned out. It was summertime—the sweaty months of June or July—and Stacy was at work. I think it was a Friday night, and I bought a gallon jug of vegetable oil and a spray bottle and a wheelbarrow full of wood for $25. Treating the cooker like a cast-iron skillet, I sprayed it all over inside and out, rubbed it down with towels, and got it looking like new. That was love. Then I packed the thing full of wood and built a raging fire to burn it out, season the smoker, incinerate any remnants of the cleaning process, and seal up the pores in the metal that I’d exposed through cleaning. That was probably a 500°F or 600°F inferno with flames coming out the door. I let it slow down a bit, choked off the fire with the door, and then went to H-E-B to find whatever was on sale. I just didn’t want to waste the fire. What was on sale was pork ribs, which became the first rack of ribs I ever cooked in my life.

After that, Number One sat around for quite a while. I would have loved to fire it up again, but what business did I have hosting a huge barbecue when Stacy was really paying the bills? She and I were both working a lot, only she was working for money, and I was working on houses for friends with some vague faith that it would all pay off. In the meantime, the friends I was working for were covering my expenses, and I was amassing a good collection of tools that would eventually come in handy when it came time to open my own joint.

We did smoke a couple of delicious turkeys for Thanksgiving one year. But other than that, Number One just sat in the driveway. We were working and trying to save money, because by now I was fully committed to opening a place. I spent most of my time mapping out the process of somehow opening a place someday. But money had gotten a bit tight, because apparently one guy (me) building a house takes a really long time.

Consequently it had been about a year since we’d last had a barbecue, and I was really jonesing at this point to have the mother of all barbecues. Eventually, we took some money and really did it up. If I thought I was a badass the last time I walked out of H-E-B with two briskets, think about how I felt pushing out a cart carrying six! Total baller. We had sawhorses in the backyard that we used to support a sheet of plywood for the cutting table. We really thought out the flow of service, with everything I needed to cut the brisket easily at hand, all the sides and garnishes lined up after the brisket station, drinks in the back of a defunct 1966 Chevy truck whose bed we filled with ice.

We even made little handbills to pass out to friends with directions to our place. I stayed up all night working on the meat; making potato salad, coleslaw, and beans; and keeping the fires. The previous day Stacy had said, “People are really going to show up today. I think this is going to be bigger than you expect.”

A WORD ON TEXAS BARBECUE

Making barbecue from pig is not as common in Texas as it is in many other states. The other major barbecue styles in the United States are largely pork-derived. Kansas City is famous for pork ribs and burnt ends, Memphis for its wet (sauced) and dry (rubbed) pork ribs, and North Carolina for its whole hog barbecue and pulled pork.

Texas is mostly associated with beef, though we cook our share of pork too. But really, the state is notable for its diversity. Most folks who travel through Texas for the first time are surprised by what they see. People, especially if they’re from other continents, expect the state to look like the desert backdrop of a Road Runner cartoon. But when you live here, you know that this massive state has a diverse landscape, from the lush bayou of the east, to the plains of the panhandle, to the coastal flats of the south, to the Road Runner-esque desert mountains of West Texas. Texas barbecue is just as diverse as its terrain and, indeed, is heavily influenced by that terrain. Classic West Texas style, sometimes known as “cowboy style,” involves simply slow-cooking meat directly over mesquite coals. (Mesquite is one of the few trees that grow plentifully out there.) Bordering Mexico, South Texas boasts a barbecue influenced by Mexican barbacoa, which is all about smoking goat and lamb and cow heads wrapped in leaves and buried in a pit in the ground. East Texas is next to Arkansas and Louisiana and takes its cues from the cooking style of the Deep South, so you see more pork here, and the wood of choice is hickory and pecan. Central Texas barbecue, which is the style I mainly adhere to, is all about slow cooking in offset smokers on post oak, which grows plentifully in a large part of Central Texas. Meats are brisket and ribs, and every restaurant tends to have its signature sausage recipe too, thanks to the large German and Czech heritage around here, which is also why we have a kolache culture in many small towns in these parts.

Which is best? They’re all delicious, of course, so long as the person cooking knows what he or she is doing.

I didn’t agree, but then on the day of, we started to get call after call from people all planning to come, asking if they could bring friends. It suddenly hit us that we were in big trouble, so we ran out and rented some tables and chairs. We strung lights and hung flood lamps from the huge pecan trees in our backyard. Plugged in a stereo. Made sure we had enough ice to chill the beer that people were asked to bring.

Before I knew it, there were 130 people ambling into the backyard. I got distracted and kind of overcooked the brisket—or so I thought. In fact, it turned out incredibly, the best I’d ever made up to this point, and I took note: brisket needs to cook a lot longer than you’d think to get tender. The guests all formed a line that wrapped around the backyard and down the driveway, and I was there at the cutting board cutting for each and every one of them.

And that’s when I hit some sort of stride on this barbecue thing. Something just clicked and it felt so incredibly natural, so good. And it must have seemed that way to others too, because they kept asking me, “So when are you going to open up a place?”

I said, “I don’t know, but I really want to someday.” Little did I know that, encouraged by the success of this massive party, it was going to be sooner than I thought.

THE TRAILER

In 2008, the now-overgrown food truck scene in Austin was just getting started. Stacy and I knew—had known for some time—that we wanted to open a barbecue restaurant of our own. The only question was how: we were still poor, still just working to get by.

Then Stacy found the trailer. It was posted to Craigslist, a 1971 Aristocrat Lo-Liner. I’ve been talking a lot about my love of Americana, roadside attractions, and the like—well, this trailer fit the mold perfectly.

Now, I hadn’t really intended to join the “mobile kitchen” movement—but hey, the Artistocrat cost $300, and we figured we should make a go of it.

“It’s a piece of junk,” Stacy said, looking up from the computer.

I said, “That’s great. That’s all we can afford.”

Stacy was right; the trailer didn’t look like much. But I was already envisioning its future as a mini-restaurant: parked somewhere, with Stacy and me inside, her taking orders and running the register, me cutting meat to order and running out back to check on the smokers when necessary. If we set up some picnic benches out front, people could enjoy their barbecue on-site. It could be perfect.

So we drove out to the property where this trailer was marooned, welded to a boat dock. Inside, it had old beer cozies from the Yellow Rose, a local gentleman’s club, and a couple of active wasp nests. The thing needed to go to the dump, but instead it was going to our house. The trailer was in such bad condition that I didn’t feel comfortable towing it home, so we actually paid to have the thing brought to our house on a platform truck.

It sat in our backyard, resting on bricks, for a long time. We were still busy, working on other things, and I was trying to decide what to do with it. I sat in it quite a bit, drank beers in there while trying to visualize how it could eventually be configured.

One of the things I was doing at the time was helping my friend Travis Kizer renovate and build out his coffee roastery. He had this place, an old, late 1940s-early 1950s derelict gas station in the heart of Austin on the access road to Interstate 35, not far from the University of Texas campus, not far from where we lived. We’d work on it every night (because we had other work during the day) sometimes until 3 or 4 in the morning. I was really into it, because Travis is one of the best people I know and because I love old gas stations. (It was thrilling to discover that this one, underneath all sorts of horrible paint and ruin, was a Texaco station from 1951. These stations, which were masterworks of art deco, were designed by Walter Dorwin Teague, who also designed some of the popular Kodak Brownie camera models. But I digress …)

I remember one night sitting on the tailgate of Travis’s truck, drinking a beer, talking about roadside America, since we were right on the side of a highway. He said, “You’ve got that trailer at your place, right?”

“Yeah, had it for a while. I just want to open up a barbecue truck so bad.” I was just too busy, too short of funds, and didn’t know how to get the thing started.

Then Travis said, “You should renovate that thing and just park it here. If you ever make money, you can give me some rent.”

I looked at him and said, “Are you serious? Has the beer gotten to you?”

I called Stacy at about 4 a.m. on my way home, even though I was only two minutes away. “Stacy! Guess what? I got a place for the trailer!”

I couldn’t sleep a wink that night, my mind was exploding with ideas. Somehow, Travis offering a space was the equivalent of the light turning green for me. It had been yellow, but now it was green. I suppose I was waiting for it to happen when it was naturally meant to happen. And, amazingly, it’s analogous to the very nature of barbecue: you never know exactly what’s going to happen. You know how you want it to turn out, but you can’t force it, and you can’t make it happen on your schedule or in your time frame … you can only guide it. Same thing with a little dream of opening a place: I knew it was going to happen and what it was going to look like, but it would be ready only when it was ready. After this moment, I threw myself into getting the barbecue trailer going with greater energy than I’d ever thrown into anything.

I called my mom the next day. “I think I’ve got a place for the trailer.”

“Oh, that’s nice, sweetie.”

“No, seriously! I have a place!” Yes, it was going to be inside a chain-link fence behind a run-down building with no sign, on the side of a major interstate between a strip club and an adult bookstore. But we had a place!

My grandmother had died recently and left my parents some money. They knew my ambitions well and decided to help me out. As they got money, they would transfer it to my account, and I’d go buy a counter or a sink. I was so grateful.

We started gutting the trailer, and every day I’d take it apart, cut holes, install things. We continued to scour Craigslist for everything we possibly could. We found a used sink, a cash register, a food warmer, a refrigerator, a little stove. Just the cheapest things I could find. Our backyard, littered with junk, looked like Sanford and Son.

So, piece by piece, I started to put it all together. And the trailer was beautifully designed, if I do say so myself. It was outfitted like the cabin of a boat or a submarine—the most ergonomic, tight-fitting, efficient use of tiny space you could imagine.

Everything inside was either from Craigslist or scavenged. I started pulling out pieces of wood and other bits of shelving and metal I’d saved from my various construction jobs. (I’d been working these for a couple of years now, always with the trailer in mind. If we tore off the panel from a kitchen door or a good piece of wood, I’d save it. The backyard looked like it belonged to hoarders.)

The food truck permit we were getting stipulated that all of our food had to be served from the trailer, and all the sides we served had to be made in the trailer—I couldn’t make stuff in our home kitchen and just bring it over. So we wired up the whole thing for electricity. I converted a little old stove to propane. Overhead and down below, I built tight, round-edged shelves for spices, plates, cups, lids, bus tubs, side dishes, bread, butcher paper. There was a neat little pocket for a slide-in trash can I could pull out with my foot when I needed to sweep something off the cutting board. I installed an 11-foot countertop, measured precisely for my dimensions: I took into account how far beneath it my toes would hit the baseboard, and I lowered the counters from standard 36-inch serving height to compensate for both the 1½-inch cutting block and the towel beneath it.

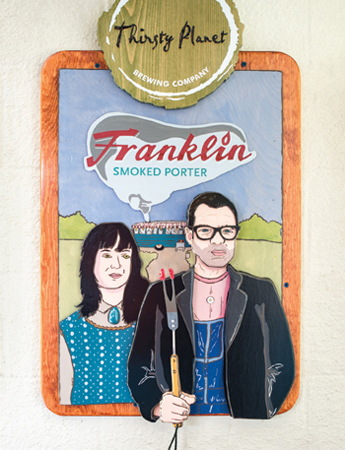

In December 2009, we put a used marquee up by the I-35 frontage road that said FRANKLIN BBQ OPEN. We’d festooned the freshly outfitted and ready-for-business camper and the trailer housing Number One with white, orange, and red lantern lights for as festive a vibe as you could muster in such a weird location.

It was cold—in the mid-40s, overcast—and I was a bundle of nerves. My stomach was in knots. It was heartening then that my first customers were Big Jeff Keyton and his wife, Sarah. There were probably twenty-five customers that day, and they were all friends. But it was a good day. And every day thereafter got a little bit better, although the weather wasn’t great and we were heading into the holidays. As it got busier and busier, I could see how tough it was going to be. Benji came around and helped as much as he could. And Stacy worked with me on the weekends, when she wasn’t at her other job.

At first, everything was cooked on Number One. The briskets were pretty darn good right out of the gate. The ribs were a little shaky. The pulled pork was fine. This was when I really started learning. I kind of thought I had a handle on things before I opened the trailer, but I quickly realized that I did not. It’s when you start doing something multiple times a day, every day, that you really start to get better.

Early on, it was a real cool vibe. I could put a brisket on after lunch and watch it until 8 or 9 o’clock at night while drinking a beer. In the evenings, I’d fire up a huge pot of potatoes, which I’d peel for an hour and half each day, dicing them all by hand because it was cheaper to buy cases of whole potatoes. After I shut down, I still had the fires going. I’d of course have to run various errands, get dinner, go home. But I’d always rush back, throw a log on, wait by the fires for a little while. At some point in the night, I’d get the fires going and then head home to sleep for a few hours before speeding back to stoke up the fires again and finish things off.

But it was pretty insane in there when it got busy. (At that time, a long line was ten people.) During the week, when I was all alone, I had to bounce between cutting, register, and fire. I’d be waiting inside my little camper for someone to show up. I’d open the window and ask what they wanted. I’d cut the meat and scoop the sides. Then I’d wash my hands, take their money and give them their change, wash my hands again, and go back to serve the next customer. The trailer with Number One in it was positioned such that I could look out and read the gauges. When I saw the temperature starting to dip, I’d ask the customer to excuse me and I’d go out to throw a new log on the fire.

Within a month or so, as we got busier, I got a guy to help out a few days a week. That’s how fast things were moving. Quickly, the stove inside became too small for cooking the amount of beans and sauce we needed. We outgrew that and had to start using a turkey fryer. At first, I would pick up one or two briskets every morning, but we started having them delivered instead. We had no place to put them, however. We couldn’t use a commissary kitchen, because I had to be there watching fires. You can’t leave and then transport things, because you can’t be in two places at once, which has been a common theme for the last four years.

I also needed additional space to cook more and more meat, and I had to figure out how to find enough space on the cooker for all the meats that had to be smoked. That’s how we created the little systems we have now of cooking the briskets all day and getting them off to rest in time to get the ribs going for that day’s service. Even then I didn’t have the room. Of course, that all became ancient history the day after we got our first review.

The review was by Daniel Vaughn, who then had a barbecue blog called Full Custom Gospel BBQ. He went around Texas and the country rating barbecue joints. It’s worked out well for him. Now he’s the barbecue editor for Texas Monthly magazine. The review was stunning. “It’s been a while since I’ve found an honest ‘sugar cookie’ on my brisket,” he wrote, “but as I waited for my order to be filled, owner and pitmaster Aaron Franklin handed me a preview morsel from the fatty end of the brisket and the flavor was transcendent. If I lived in Austin, I would go here every day if I could be guaranteed a bite like that one.”

That came out at the end of January, only our second month, and that’s when people started showing up before we opened. Every time I hear the song “Alex Chilton” by the Replacements (big fan), I think of this. It was a Saturday morning, beautiful, and “Alex Chilton” came on. I was drinking a coffee and the line was down the fence getting close to I-35. And we were so exhausted, but I just remember that moment, looking at this line thinking, What have we done? This is the craziest thing ever. When is this going to stop? Well, it hasn’t yet.

By the time the South by Southwest music festival, Austin’s most insane week of the year, rolled around in March, we were already rocking and rolling, serving at capacity to a line most of the time. Lines were stretching around the corner, and the wait was longer than an hour. I realized, Oh my goodness, I’m going to need another smoker, and somehow I found some time over six months to build Number Two, which joined Number One in producing our meat. In June 2010, Stacy quit her job to come work with me. (First two weeks: pretty rough trying to figure out how to work together. After that it got smoother.) By that fall, we just couldn’t handle the traffic out of our little makeshift restaurant in a parking lot. So we started looking for a real space. And that’s when we found the restaurant.

FRANKLIN BARBECUE: THE RESTAURANT

In a lot of ways, our restaurant-opening story is similar to all the other restaurant stories out there. So I won’t spend too much time telling it. After running the trailer for about eleven months, we just couldn’t handle the amount of business anymore, and we knew that we needed to look for a real place.

We started looking at spaces, but there was one barbecue place that I’d been scoping out for a long time. It was clearly failing, and coincidentally went out of business right about the same time we were looking for a place. I had a commercial real estate buddy get in touch with the owner; he said the last tenants hadn’t paid rent in a while.

The guy who owned the business ended up quitting. I think he’d been doing one cook a week and then cutting cold brisket and microwaving it for individual plates. After he left we walked in, and I’m surprised that we didn’t get E. coli just from inhaling the smell of this place when we opened the door. The cutting board still had bits of meat on it, the knife was sitting where the previous guy had left it, and there was an apron hanging on the light switch. You could tell that one day he was cutting lunch and just said “screw this” and left. The utilities had been shut off for weeks, but he had chickens in the fridge. There were crumbs all over the counter from his cookies and all of the sinks were full of standing water.

For us, the timing couldn’t have been better. We signed the lease on the restaurant almost a year to the day after we opened the trailer. It took three months to build it. Benji and I and Braun and Stacy, we gutted it all, worked our fingers to the bone, did all the carpentry ourselves. When we opened for business in this location on East 11th Street on the first day of SXSW (a famous Austin music, film, and interactive conference/festival), some of our more devoted fans slept outside overnight, determined to be the first in line.

Since then, we’ve sold out of meat every single day of our existence. We get visitors from all over the world; if you stand in line on any given day, you might meet some kids from Japan who are in the middle of a Texas road trip, a family from Colorado who drove all through the night to get in line at 9 a.m., or some students from the nearby University of Texas who decided to claim a bit of brisket before their afternoon classes. We even got a visit from the President of the United States. In the summer of 2014, we renovated for the first time since opening and built a smokehouse to make things run more efficiently. So far, so good. Since opening the trailer in 2009, it’s been an eventful and exhausting haul to get this far. And I don’t regret one second of it.

WHY DO BARBECUE JOINTS KEEP THESE ODD HOURS? IT’S HISTORY.

Yes, I realize that my restaurant is technically open for only about four hours a day. People ask sometimes, “Why aren’t you open longer?” or “Why don’t you open for dinner?”

To answer the first question, we’re open for only those short hours because we close when we run out of meat. And we run out every day because supply is less than demand—for the simple reason that we don’t have enough real estate on the smokers. Between briskets and ribs, not to mention pork butts, turkeys, and sausages, the smokers are running at pretty much max capacity twenty-four hours a day. In the summer of 2014, we added a new smoker to the lineup, which increased our capacity slightly. But each of our smokers is incredibly heavy and over 20 feet long. I don’t want to sound as though I’m making excuses, but the bottom line is that “increasing production” isn’t as easy as it might sound.

As for that second question, why we don’t open for dinner: it’s a good one, and one I often ask myself. After all, there are things about a dinner service that make sense. For instance, I (or whoever is cooking them that day) wouldn’t have to get to work at 2 a.m. to put on the day’s ribs. If we were open for dinner instead of lunch, technically, I’d have to get to work at only 10 or 11 a.m. to get the ribs going. What a nice, relaxing day!

But barbecue in Central Texas is traditionally a midday—or even morning—meal. For instance, the excellent Snow’s BBQ of Lexington, Texas, an hour east of Austin, is famously open from 8 a.m. until they run out of meat, which can often be 10:30 or 11 that morning. So be prepared to eat barbecue for breakfast if you go out there. Smitty’s Market in Lockhart (a half hour south of Austin) is open from 7 a.m. to 6 p.m. during the week, which are pretty classic hours.

To understand why Central Texas barbecue joints aren’t open for dinner, you have to understand the history. They didn’t start out as restaurants. Rather, they began as meat markets and grocery stores. People often describe the Central Texas style as “meat market” style. The style takes its cue from the large number of German and Czech immigrants who came to this part of the state, as described by Robert F. Moss in his scholarly book, Barbecue: The History of an American Institution. They arrived in the mid to late nineteenth century and became farmers, craftsmen, and merchants, bringing with them many traditions, including butchery, sausage making, and smoking meat. A number of these immigrants opened meat markets. In those days, meat markets were butcher shops, where vendors would break down whole animals and sell the meat. Lacking refrigeration, the butchers would preserve the less popular cuts of meat by smoking them or grinding them up for sausages, which they’d then sell as a ready-made meal on butcher paper, just as we still do today. These places weren’t restaurants, so they didn’t even offer silverware, sides, or sauce, just pickles and onions, a tradition some of the more famous places in Lockhart upheld until fairly recently.

The cotton industry boomed in Central Texas in the latter part of the 1800s, and before automated harvesting, migrant cotton pickers would swarm through the area for work. According to Moss, “an estimated 600,000 workers were needed for the 1938 crop … and many went to local grocery stores and meat markets for takeout barbecue and sausages.” Given the hours agricultural hands worked in the Texas summer, they’d come in to eat barbecue throughout standard market hours, from 7 a.m. to 6 p.m. Over time, with barbecue proving so popular and supermarkets taking over the niches of the little specialty stores, the meat markets evolved into restaurants, which they remain today, though we tend to keep some semblance of the traditional hours while we serve up this cuisine whose history in these parts goes back 150 years.

But I have another theory as to why barbecue has continued as lunchtime fare: it’s just too rich and heavy to eat at night. I wouldn’t really want to eat it for dinner, letting it sit ponderously in my stomach as I go to bed (and I go to bed early). Rather, it’s much better to eat in the middle of the day, when you’ve still got a lot of moving around and digesting to do.