Fukushima: The Story of a Nuclear Disaster (2015)

11

2012: “THE GOVERNMENT OWES THE PUBLIC A CLEAR AND CONVINCING ANSWER”

On January 18, 2012, protesters attempted to gain access to a closed-door meeting of Japan’s Nuclear and Industrial Safety Agency (NISA). More than a hundred uniformed and plainclothes officers arrived to quell the scuffle. A green and yellow sign held aloft by one of the well-dressed demonstrators read: “Nuclear Power? Sayonara.”

Before Fukushima Daiichi, that prospect seemed unlikely. Japan was firmly wedded to nuclear power—economically, politically, and socially. But now, as the consequences of the accident ten months earlier continued to unfold, to many Japanese the marriage was difficult to defend. The demonstrators being jostled in a crowded hallway and chanting “Shame on you” to the authorities sequestered behind the doors were part of a new, vocal constituency intent on having a say on Japan’s energy future. For them, the price of nuclear power was just too high.

Since the accident, much had changed across Japan; 2012 would become a year marked by protests, uncertainty, and shifting political allegiances. Although Fukushima Daiichi officially was in cold shutdown, the popular debate over nuclear power was increasingly active. On numerous occasions, public opinion boiled over at politicians who seemed tone deaf to the concerns of average citizens. The country’s leaders—in government and in the clannish private sector—appeared determined to close the book on the disaster of March 11 as quickly as possible and begin restoring the role of nuclear power as an essential element in Japan’s economic life.

Immediately upon taking office in September 2011, Prime Minister Yoshihiko Noda had made his views clear: Japan needed nuclear energy. Noda proposed a middle ground—one that he hoped would ease public fears about living with nuclear power and corporate Japan’s fears of living without it.

“[I]t is unproductive to grasp nuclear power as a dichotomy between ‘zero nuclear power’ and ‘promotion,’ ” said Noda. “In the mid- to long-term, we must aim to move in the direction of reducing our dependence on nuclear power generation as much as possible. At the same time, however, we will restart operations at nuclear power stations following regular inspections, for which safety has been thoroughly verified and confirmed.” If the public could be convinced that Japan’s reactors were safe, perhaps the marriage could be saved.

The “how safe is safe enough” threshold for many Japanese had soared in the months since March 11, however. In normal times, safety inspections had been largely pro forma, conducted out of view, with little or no public input. Everybody had seen what that produced. If Noda thought his proposal to restart the nation’s reactors would win public support, he quickly discovered otherwise.

Within days, tens of thousands of protesters took to the streets of Tokyo. The September 19, 2011, protest was the largest public demonstration in years in the capital. They wanted every reactor in Japan shut down permanently. A sign held by an elderly protester depicted a mother cradling an infant. It read: “This child doesn’t need nuclear power.”

On September 19, 2011, tens of thousands of protesters clogged the streets of Tokyo, demanding an end to nuclear power in the country. Here protestors gather at the Meiji Shrine Outer Garden in the nation’s capital. Wikipedia

✵ ✵ ✵

After being escorted out of their meeting room to avoid the noisy protestors, NISA officials reconvened and approved the restart of two reactors at the Ohi nuclear plant in Fukui Prefecture, on Japan’s west coast. At this point, only three of the country’s fifty-four reactors were still operating, and those would also soon be turned off. Before any could be restarted, all were required to pass the safety checks first ordered by former prime minister Kan and now cited by Noda: a first round of government-ordered “stress tests.” Plants that passed the first-round tests would then undergo a second, more comprehensive round that would determine whether plants were safe enough to continue to operate.

The first-stage tests were designed to verify a reactor’s ability to withstand specific events, such as beyond-design-basis earthquakes, tsunamis, or both. Taking a lead from the European Union, which ordered stress tests for all one hundred thirty operating plants within its jurisdiction after the March 11 accident, the Japanese government directed the nation’s utilities to perform similar tests. However, the guidelines were vague, failing to specify clearly how far beyond the design basis the assumed stresses should go. That made the outcomes of the tests hard to interpret.

The results of the first-stage tests were submitted to NISA, which then passed on its plant restart recommendations to the Nuclear Safety Commission. The commission, in turn, forwarded its decision to the prime minister. Noda and several of his cabinet members would have the final say.

Even as the government proceeded through the formalities of the stress tests, pressure was growing from several influential constituencies to bring the reactors back online as rapidly as possible. A recurrent theme among the restart supporters was that Japan was headed for a major electricity shortage. That moment was approaching, along with the hot, humid months, when energy use normally would rise by about 50 percent. Unless Ohi Units 3 and 4—the first reactors in line in the stress test review process—were restarted, Japan would be nuclear free on May 6, 2012.

That prospect posed a worrisome “what if?” for restart advocates. Suppose Japan successfully made it through the summer without nuclear power. That would make it more difficult to win public support for returning the plants to service.

To add credibility to NISA’s conclusion that the Ohi reactors were safe, the Noda government invited a delegation from the IAEA to review the findings. Based on a preliminary assessment, the IAEA reported that the stress tests were “generally consistent” with its own safety standards and supported “enhanced confidence” in the reactors’ ability to withstand even a disaster similar to that of March 11.

Those findings drew a scathing public rebuke from two nuclear experts who served as NISA advisors. The tests, the two men said, failed to take into account complex accident scenarios as well as critical factors such as human error, design flaws, or aging equipment. At a news conference, Masashi Goto, a former reactor designer, labeled the stress tests “nothing but an optimistic desk simulation based on the assumption that everything will happen exactly as assumed.”1 Goto also argued that the stress test methods should first be applied to Fukushima Daiichi to see if they could correctly simulate the outcome of the accident.

The other expert, Hiromitsu Ino, a professor at the University of Tokyo, accused the IAEA of simply rubberstamping NISA’s decision because of the international agency’s dual role as regulator and promoter of nuclear power. Ino noted that the IAEA had deemed the Kashiwazaki-Kariwa nuclear plant safe after a 2007 earthquake without conducting a full examination of the plant.

Ino’s and Goto’s sharp critiques were echoed two weeks later by another expert: Haruki Madarame, the head of Japan’s NSC, who had been at Prime Minister Kan’s side during the height of the accident. In a declaration that must have surprised many, Madarame asserted forcefully that Japan’s nuclear regulatory framework was flawed, out of date, and below international standards. He claimed that the government’s foremost concern was not protecting the public but promoting nuclear energy. Madarame added that Japan had become overly confident in its technical superiority, failing to acknowledge the risks that nuclear power posed, especially in an earthquake-prone country. Concerning the stress test results, he said: “I hope there is an evaluation of more realistic actual figures.”

The IAEA’s final review of Japan’s stress tests, released in March, appeared to support some of the critics’ concerns. The agency said that NISA had not communicated what its desired safety level was or how the assessments could demonstrate it. Regardless, the IAEA’s overall judgment did not change.

For many Japanese, the epiphanies of such once-staunch nuclear proponents as Kan and Madarame only heightened uncertainty and confusion. Before March 11, 2011, they had been led to believe that their country’s reliance on nuclear power was a prudent choice. Now, knowledgeable insiders were painting the entire nuclear framework as a public threat and an embarrassing fraud. And at the same time, the leadership in Tokyo was pushing to restart reactors.

If criticism from Japan’s own experts wasn’t unsettling enough, international disapprobation soon followed. A group of experts summoned by Yotaro Hatamura’s investigative committee, which was wrapping up its lengthy assessment of the accident, weighed in. Because the Hatamura panel focused on TEPCO and events at Fukushima Daiichi, much of the criticism was directed at the utility, but the message spilled over: the failings were systemic. For example, Richard Meserve, former chairman of the U.S. NRC and president of the Carnegie Institution for Science, said that not only had TEPCO become overly confident but Japanese regulators had followed suit, falling victim to the myth of safety. “There has to be a willingness to acknowledge that accidents can happen,” said Meserve.2

At the moment TEPCO was in a fight for its own survival. A company that many believed was too big to fail would soon become a ward of the state. This was more than just a corporate icon falling on hard times. Soon, the cost of TEPCO’s lax oversight, failed planning, and propensity for high-stakes gambles would shift from a private debt to a massive public one.

Estimates of the cost of cleanup and compensation to victims of the Fukushima Daiichi accident were pegged at more than $71 billion (6.6 trillion yen) by late 2012. Much of that burden will fall on the shoulders of Japanese taxpayers, already suffering from a deeply troubled economy.

As Japan marked the first anniversary of the Fukushima Daiichi accident, the magnitude of TEPCO’s financial woes was growing. The plunge in the company’s stock price had erased almost $39 billion in market value, according to one analysis. Without an infusion of cash, the utility—which employed 38,000 people and supplied electricity to about 45 million, including those living and working in the world’s largest city—almost certainly would collapse.

Private lenders and institutional investors were wary, wanting the government to craft a rescue. No one could say with any certainty just how much this all was going to cost. Rumors that the government was going to nationalize TEPCO were initially rebuffed by Trade Minister Yukio Edano. But an intervention of some sort increasingly seemed to be the government’s option of choice—and TEPCO’s only hope.

The utility’s leaders remained defiant, asking Tokyo for money but rejecting any government say in company operations. Leading the fight to keep TEPCO under the control of insiders was its chairman, Tsunehisa Katsumata, one of Japan’s best-connected business leaders. Although Katsumata planned to step down in a show of responsibility for the accident, he argued that only TEPCO executives knew how to run the company. Edano countered that TEPCO’s corporate culture “hasn’t changed at all” and that new management was necessary.

Some economists and energy experts saw TEPCO’s dire predicament as a golden opportunity to restructure Japan’s antiquated energy supply system by breaking up utility monopolies and introducing competition. “Since the 1980s the utilities have looked more like bloated government departments than red-blooded businesses,” a writer for The Economist noted.

Unlike energy markets in the United States and elsewhere, in which generation and distribution had been separated, opening the way for competition, in Japan the ten regional power companies held total monopolies on all aspects of energy supply. The result was reliable service but at a very high price. The monopolies were extremely lucrative for the utilities.3 An analysis by Bloomberg News found that the ten of them earned $190 billion in annual revenues from generating, transmitting, and distributing power. Shattering that stranglehold, some Japanese academics and international analysts believed, could open markets, reduce rates, give renewable energy a toehold, and possibly lessen Japan’s need for nuclear energy.

To critics of the status quo, the months following the accident had provided some hope that change was possible. During the summer of 2011, the government had imposed power restrictions on large corporate users. Voluntary conservation efforts had been surprisingly successful. Electricity consumption during steamy August had dropped by about 11 percent. The usual chill of air conditioning was gone, as were coats and ties. Some manufacturing operations moved to off-peak nights and weekends. Even some night baseball games were switched to daytime. That led to speculation that reduced consumption could become the norm and there would be no need to restart the reactors. The nation stood at a crossroads, activists argued, needing only visionary leadership to map out a new energy policy.

But those hopes gradually faded as it became clear that Japan, still struggling to recover not only from a nuclear disaster but from a massive natural disaster, was unable or unwilling to take on such a challenge. Restructuring the electricity distribution system was not a priority. Keeping TEPCO alive was, however.

In late March 2012, TEPCO requested $12 billion (1 trillion yen) from the government to stay afloat. The price, as company officials knew, was the end of their independence; the government would take over control of the utility.4 Breaking with the utility’s long tradition of promoting executives from inside, the government brought in Kazuhiko Shimokobe, a bankruptcy lawyer and turnaround specialist, to be TEPCO’s chairman. Shimokobe, who had been running the government-backed TEPCO bailout fund, would handpick the new president. “This is the last chance to restore TEPCO,” he grimly told reporters.

The ten-year bailout plan approved by the trade ministry in early May provided $12.5 billion in government capital in exchange for more than 50 percent of the voting shares of TEPCO, with the right to increase that percentage to two-thirds if the utility failed to institute major reforms. In addition, TEPCO had to agree to a cost-cutting plan and other changes. All sixteen directors would resign and be replaced by a new board, the majority of whose members would be from outside TEPCO. The new president would be not an outsider, as some had hoped, but Naomi Hirose, a TEPCO managing director who held an MBA from Yale University.

TEPCO’s new management had to face a formidable challenge: a $9.78 billion loss for the fiscal year that ended in March 2012. A key step to move the utility back toward solvency was the restart of its seven reactors at the Kashiwazaki-Kariwa plant, three of which had been idle since the 2007 earthquake. “[A]ny plan that does not include nuclear energy would be nothing more than a pie-in-the-sky blueprint,” said Shimokobe, who along with Hirose was slated to officially take over following shareholder approval in late June.

By late June, when Japan’s power companies held their annual meetings, it was evident that TEPCO wasn’t the only utility opposed to a nuclear phaseout. Shareholder proposals to reject nuclear power were soundly voted down at all the meetings. Unsurprisingly, the utilities’ main institutional investors—life insurers and banks—voted with the company managements on this issue. The status quo seemed to them a safer bet. In the end, stockholders approved the bailout plan and the ongoing commitment to nuclear power.

Indeed, the recovery plan barely mentioned any energy strategies beyond restarting the utility’s nuclear plants. The influential Asahi Shimbun editorialized that TEPCO was getting off too easily. The utility should be forced into bankruptcy and the company’s shareholders and creditors should be “made to pay the price for their own mistakes.” Only then would it be right to tap the Japanese public for help in a recovery.

As of May 6, 2012, Japan had no operating reactors. Without them, the system was shy of roughly fifty gigawatts of generating capacity—about what Tokyo consumes during peak periods. With no nuclear power in the mix, Japan would require an additional three hundred thousand barrels of oil every day, along with an annual import of 23 billion cubic meters of natural gas to meet electricity demand, according to International Energy Agency estimates. (The cost of this imported fuel was expected to more than double residential electricity bills across Japan and further hobble the nation’s troubled economy.)5

Although the media had spent months speculating about a Japan without nuclear power, others never doubted that the reactors would eventually restart, given the depth of institutional support for nuclear energy. On March 23, the Nuclear Safety Commission ruled that the stress tests performed on Ohi Units 3 and 4 were satisfactory. And on April 13, Noda announced that the two Ohi reactors could safely resume operation. All that remained was the approval of local officials, no longer a sure thing for those who saw the devastation Fukushima had brought to nearby communities.

This rush to fire up the reactors made no sense to many in Japan. The accident at Fukushima Daiichi was still being investigated and many critical questions remained unanswered. The current regulatory system had clearly proven itself inadequate, yet the creation of a new agency to replace the discredited NISA was tied up by political infighting. For now, safety matters remained in the hands of NISA and the NSC—the same two agencies that had said Japan’s reactors were failure proof. If restoring public trust was the government’s top priority, many asked, what was the rush? Why not await creation of the new safety agency and give it the authority to develop its own criteria for restarts?

Adding to worries was the release of new seismic data showing that a large portion of western Japan, including Tokyo, was vulnerable to earthquakes nearly twice as large as what the government had projected just nine years earlier. Coastal areas along this same part of Japan also were found to be vulnerable to tsunamis of thirty-two feet (ten meters) or more, three times higher than previous projections. The area around the Hamaoka nuclear plant, southwest of Tokyo, could be hit by a tsunami of sixty-eight feet (twenty-one meters), far above previous predictions. Unlike remote Fukushima, this region was densely populated.

The data also identified previously unknown and potentially active faults located in areas near or even directly underneath, Japanese reactors, including Ohi. Even when presented with the new seismic information, the utilities and government dismissed the potential hazards as exaggerated, without documenting their claims.

“[I]s it really possible to ensure the safety of operating these reactors while the possibility of active faults lying beneath them cannot be ruled out?” the Asahi Shimbun asked in an editorial. “The government owes the public a clear and convincing answer to this question.”

✵ ✵ ✵

The Ohi nuclear plant sits along Japan’s scenic west coast, about sixty miles northeast of Osaka, Japan’s third-largest city. Comprising four pressurized water reactors, the plant is owned by Kansai Electric Power Company (KEPCO), which relies on nuclear power for almost half its generating capacity, more than any other Japanese utility. Ohi Units 1 and 2 are older PWRs with ice-condenser containments that are smaller and weaker than the large, dry containments at Units 3 and 4. Perhaps for that reason, KEPCO proposed restarting only Units 3 and 4 at first.

In many respects, Ohi served as an ideal test case for both those promoting and those opposing the restarts. The plant is in Fukui Prefecture, home to a total of thirteen reactors. The local economy was heavily dependent on the jobs, tax revenues, and generous perks provided to local communities by utilities doing business there. Some of Japan’s largest manufacturers, including Sharp Corporation and Panasonic, are KEPCO customers. The possibility that they and others might move operations offshore if uncertainty regarding energy supplies continued was a clear concern in Tokyo.

Despite their economic benefits, not all neighboring communities were eager to see the Ohi reactors returned so quickly to service. Having a nuclear neighbor once seemed attractive to nearby towns, but that was before they had witnessed the consequences of an accident—the depopulation of a large region, widespread contamination, health risks, uncertainty about a return to normal life. At the height of the restart debate, the government announced that 18 percent of all Fukushima evacuees—including those as far as thirty miles away—might not be able to return to their homes for ten years because of radiation levels.

As a result, some argued that if communities tens or even hundreds of miles away were vulnerable to nuclear plant accidents, they too should have a say in the plants’ operation. And the calculus might be different for such communities, since they would be exposed to the risks without receiving any of the benefits. That was something new in Japan.

One of the most outspoken restart critics was Toru Hashimoto, the brash young mayor of Osaka, whose city was Ohi’s largest customer and also the largest shareholder in KEPCO. Hashimoto argued that the government was prematurely pushing the restarts at the expense of public safety, a contention that catapulted him into the national spotlight and earned him a large following. Dissatisfied with Tokyo’s assurances that the plant was safe, Hashimoto set up his own panel of experts, who took issue with the adequacy of the stress tests. That prompted governors of two nearby prefectures to demand a more thorough inquiry into Ohi’s safety before Units 3 and 4 were returned to service.

Critics noted that the stress tests represented just the first phase of what was supposed to be a multipart safety response to the Fukushima accident. Additional measures—construction of higher seawalls, better protection against earthquake damage, improved emergency planning, filtered venting systems—could take years to complete. In the meantime, however, the plants would be operating.

With opposition from local officials and weekly demonstrations in the capital threatening to derail plans for a quick restart at Ohi, Prime Minister Noda stepped up the rhetoric. “Japanese society cannot survive” without the reactors, he warned on national television. And he offered assurances that the government would “continue making uninterrupted efforts” to improve nuclear safety.

The growing pressure from Tokyo and Japan’s business community had its effect. Local government opposition to the Ohi restart faded, with officials, including Hashimoto, agreeing to a “limited” restart at least through the summer months.

On June 16, the Noda government officially gave the go-ahead to restart Ohi Units 3 and 4. Trade Minister Yukio Edano acknowledged public opinion polls were running solidly against the restart. “We understand that we have not obtained all of the nation’s understanding.”

That was evident six days later, when an estimated 45,000 people protested the decision outside the prime minister’s office; thousands of demonstrators also rallied in Osaka and elsewhere. The following Friday, an even larger protest massed in the capital near the prime minister’s office. As he left for the day, Noda shrugged off the protesters. “They’re making lots of noise,” he told reporters before heading home.

It would take several weeks for the two Ohi reactors to be brought fully into service, in time to meet what the government had predicted would be a 15 percent shortfall in energy supplies in western Japan during the hottest days of summer. On July 16, with temperatures above ninety degrees, tens of thousands of people clogged central Tokyo protesting the restart. Whether the giant demonstration would have any effect on Japanese energy policy was uncertain. But the crowd, waving banners and holding up signs, made clear that it was time that the public had a say in those decisions. As a marcher told a reporter, “It’s just a big step forward to start raising our voices.” Despite the protests, in September the government authorized their continued operation.

✵ ✵ ✵

In the United States, those who had hoped for change also were feeling frustrated. Among them was the NRC’s Gregory Jaczko.

Shortly before leaving his job as chairman in July 2012, Jaczko offered a candid observation to a Washington audience of energy insiders: “I used to say the one thing that kept me up at night was the thing we hadn’t thought of. Today, the things that keep me up at night are those things we know we haven’t addressed.”

It had been a year since the NRC’s Near-Term Task Force had made its recommendations on a plan of action, including far-reaching structural reforms. But the slow pace of actual reform bothered Jaczko.

Although many details of the Fukushima Daiichi accident were still being analyzed around the world, its most obvious lessons were clear. Nevertheless, the NRC, bolstered by the task force’s statement that the U.S. nuclear fleet did not pose an “imminent risk” to public health and safety, ultimately elected to water down the most pressing recommendations and to slow-walk the others. Just as in the aftermath of Three Mile Island, it appeared that the NRC might be pulling its punches in the face of industry resistance.

In a July 2011 letter to the commission, Marvin Fertel, president of the Nuclear Energy Institute, had thrown down the gauntlet. While conceding that “the industry agrees with many of the issues identified by the task force,” he cautioned that “the task force report lacks the rigorous analysis of issues that traditionally accompanies regulatory requirements proposed by the NRC. Better information from Japan and more robust analysis is necessary to ensure the effectiveness of actions taken by the NRC and avoid unintended consequences at America’s nuclear energy facilities.” The industry appeared to be stalling—demanding further study in the belief that the passage of time would erode momentum for regulatory changes. It had certainly worked in the past.

The task force report also needed to pass muster with the rest of the NRC staff. Although the task force members were NRC personnel, they were operating as an independent body outside of the usual commission pecking order. Normally, safety rule changes evolved slowly within the agency, working their way up to the staff’s gatekeeper, the executive director for operations, a post held by Bill Borchardt.

But Chairman Jaczko wanted the commission to vote directly within ninety days on the task force’s twelve recommendations, rather than on the staff’s views of the report as filtered through Borchardt. Jaczko’s attempt to bypass senior management likely grew out of the increasingly rocky relations he was having at the NRC, not only with staff but also with his fellow commissioners, who could join to outvote him. (Jaczko would eventually accuse the majority of favoring policies that “loosened the agency’s safety standards.”) For their part, the other commissioners expected to also receive the staff’s opinions of the report, perhaps broadening their understanding or offering alternatives.

Borchardt and his deputy, Marty Virgilio, believed that the commissioners should receive a “wide range of stakeholder input” before making any decisions on the task force’s recommendations. They attached a five-page memo to the task force report making this suggestion. The memo also emphasized that U.S. nuclear power plants were unlikely to experience the same problems as Fukushima had.

Jaczko reportedly disagreed with the stakeholder recommendation and believed that Borchardt’s attachment was improperly presented based on procedural grounds. The chairman unilaterally intervened to remove the Borchardt attachment before the task force report was formally transmitted to the commissioners and to Congress. That action, among others, contributed to the internecine conflict that further isolated Jaczko within the agency and ultimately led to his resignation in June 2012.

Although back in July 2011 Jaczko had won the battle over the initial transmittal of the task force report, in subsequent votes he lost the war. Rather than vote directly on the task force’s recommendations, the majority ordered the staff to first produce a series of papers analyzing the recommendations and ranking them in priority. But the commissioners made one decision immediately: the task force’s highest priority should become the NRC’s lowest priority. Recommendation 1, to revise the regulatory framework, was put at the bottom of the list, and the staff was given eighteen months to come up with a proposal for it. In the interim, the commissioners said, the staff should use the NRC’s existing regulatory processes to assess the other recommendations.

From one point of view, this move made sense: it could take years to impose safety fixes if they had to await a new regulatory framework. But on the other hand, imposing new requirements under the old framework would only add to the patchwork of regulations and exacerbate the inconsistencies identified by the task force as part of the problem.

Given that the majority of the commissioners did not believe urgent safety upgrades were needed, the necessity for speed was not their motivation for bumping Recommendation 1 off the priority list. Rather, it was driven by the shared view, expressed in a vote by Commissioner William Ostendorff, that the current system was not “broken.”6

After putting Recommendation 1 aside, the staff proceeded to rank the others in terms of priority by putting them into three tiers. Reevaluating seismic and flood hazards, addressing station blackout risks, and improving containment vents were among the Tier 1 actions that the staff believed “should be started without unnecessary delay.”

However, the decision to proceed without first fixing the regulatory framework meant that the new proposals had to navigate all the old impediments to improving safety. In particular, the backfit rule hung over the task force recommendations like the sword of Damocles. Would the NRC buck tradition and acknowledge that U.S. nuclear plants were not adequately protected in light of Fukushima? If not, then most of the changes recommended by the NTTF would be considered “backfits” and would have to meet the NRC’s convoluted “substantial safety enhancement” and cost-benefit tests. In that case, there was a good chance that none of the recommendations would ever become a requirement.

But the old system threw up even more hurdles for change. Although Fukushima had proven that beyond-design-basis accidents were a real threat, the NRC’s obsolete guidelines still ranked them as very low-probability events, meaning that the calculated benefits of reducing the risk would also be very small. And the benefit could even be zero if the calculation addressed an event that had been left out of the risk assessment models used for the cost-benefit analyses.7

The NRC staff ultimately sided with the task force and recommended the commission approve the safety upgrades on the basis of “assuring or redefining the level of protection … that should be regarded as adequate.” But the majority of the commissioners needed more convincing. Early on, Commissioner Kristine Svinicki warned members of the task force that they were intruding into areas where they could quickly find themselves “swimming in the waters of backfit.” In an October 2011 vote, Commissioner Ostendorff asserted that “decisions on adequate protection are among the most significant policy decisions entrusted to the Commission and are not impulsive ‘go’ or ‘no-go’ choices.” This view, endorsed by the commission majority, led to yet more delay.

However, in a March 2012 decision timed for the first anniversary of Fukushima, all five commissioners approved three orders imposing new regulatory requirements without the need to pass backfit tests. Although the outcome was unanimous, each commissioner had gotten to the destination via a different circuitous route. Most contended that their actions were not expanding adequate protection but merely “ensuring” it. It all added up to a lot of confusion. But in the end, except perhaps for courts of the future that may be called on to parse these distinctions, it didn’t really make a difference.

What did matter was how comprehensive and stringent the orders were in addressing Fukushima’s lessons. And in those respects, the orders fell short on specifics.

Part of the problem was that the commissioners had directed that the requirements be “performance based.” The concept behind performance-based regulation is that requirements should not be too prescriptive. The regulator should specify the desired outcome and let the plant owner figure out the best way to achieve it. While advocates of this approach consider it more efficient because it gives owners more flexibility, it actually makes requirements harder to interpret and enforce. The industry is free to write its own playbook, leaving regulators with the burden of figuring out whether or not it meets the regulatory intent of the safety rules.

As a measure of how popular this approach is with the nuclear industry, over the past couple of decades the NEI has actually drafted guidance documents on complying with performance-based regulations, which the NRC, after some negotiation, then approved.

The B.5.b measures, introduced after 9/11 to help workers cope with the aftermath of an aircraft attack, were one case in which performance-based requirements hadn’t worked very well. The industry argued against imposing measures it viewed as too prescriptive or specific, contending that there were simply too many potential disaster scenarios to contemplate. Through their lobbying group, plant owners insisted that they needed maximum flexibility to come up with their own solutions. The NRC relented, imposing only very general requirements for the B.5.b equipment and giving the industry a great deal of leeway to design its own strategies.

However, the industry had not thought through its plans to ensure that they would actually work under real-world conditions, such as high radiation fields, excessive heat, and infrastructure damage. These were the very conditions that contributed to the failure of the Japanese severe accident management measures at Fukushima. Yet in a vote on the Fukushima proposals, the commissioners endorsed the B.5.b process as a model for dealing with beyond-design-basis accidents.

Two of the NRC’s new orders were relatively uncontroversial. One required the installation of “reliable hardened vents” at Mark I and Mark II boiling water reactors so that they could be used under station blackout conditions. Previously plant owners had been allowed to install these vents voluntarily, so that NRC inspectors had no power to review their adequacy or require improvements. This situation, a legacy of the NRC’s timid approach to dealing with severe accidents in the 1980s, provides little confidence that vents at U.S. BWRs would have worked any more effectively than those at Fukushima. The second order called for reliable instrumentation in spent fuel pools, something that could have helped workers at Fukushima better understand the unfolding situation.8

The third order directed plants to develop “mitigation strategies” for beyond-design-basis external events. But the title promised more than the order actually delivered. Plants were required to be “capable of mitigating a simultaneous loss of all alternating current (AC) power and loss of normal access to the ultimate heat sink” for all units at a site. As the task force had recommended, the strategies would involve three phases: using installed equipment, using on-site portable equipment, and using off-site equipment. But where the task force had recommended that specific durations be set for the first two phases—namely, installed equipment should be able to maintain cooling for eight hours and portable equipment for the next seventy-two hours—the order did not specify minimum durations for these phases. Each plant site would propose its own.9

IT’S RISKY WHEN INDUSTRY WRITES THE RULES

The NRC’s acquiescence to the FLEX program of rapidly deployable emergency equipment was typical of the way the agency and the industry’s advocacy group, the NEI, have interacted for many years in interpreting regulations and developing compliance documents.

In the early days, when a regulation or order needed interpreting, the NRC would develop a “regulatory guide” and submit it for comment by the affected industry. But over time the roles were often reversed: the industry, coordinated by NEI, would write the first drafts of guidance documents and the NRC would comment. This shift gave the industry far greater power to shape the conceptual basis for regulatory compliance, leaving the NRC to tinker around the edges. The NEI guidance documents would then serve as boilerplate text for use by all applicants and licensees.

The NEI guidance for the FLEX program was such a template. The NRC required all plant owners to submit plans by the end of February 2013 to demonstrate how they would implement the program to comply with the mitigation strategies order. On February 28, Exelon Corporation, which owns seventeen reactors, submitted its plan for the Peach Bottom plant in south central Pennsylvania. Exelon’s proposal was typical of all the plant owners’ responses, closely hewing to the NEI’s guidance. It clearly demonstrated the shortcomings of the FLEX approach.

The Peach Bottom plant, situated beside the Susquehanna River, has two Mark I BWRs closely resembling Fukushima Daiichi Units 2 and 3. Exelon’s plan for dealing with a beyond-design-basis accident there assumed from the get-go that batteries and electrical distribution systems for both AC and DC power would be available. It assumed that off-site personnel called to duty would be able to reach the plant in as little as six hours, not necessarily a realistic assumption in the event of the type of major natural disaster that the emergency plans were being designed for.

The Peach Bottom Atomic Power Station, located on the Susquehanna River in south-central Pennsylvania, has two Mark I boiling water reactors, similar to Units 2 and 3 at Fukushima Daiichi. Emergency response plans for the plant depend upon many assumptions now proven to be unrealistic in the aftermath of events at Fukushima Daiichi. U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission

The plan also set time frames for coping with an extended station blackout that fell short of the periods recommended by the NTTF. The task force wanted plants to be able to keep fuel cool for the first eight hours of a blackout using permanently installed equipment and thereafter using portable equipment (such as FLEX items) that was available on-site for the next seventy-two hours. After that, one could assume that additional equipment and supplies delivered from off-site would be available.

For Peach Bottom, Exelon estimated that the batteries needed to run critical equipment, including the RCIC, would last no longer than five and a half hours—but it also asserted that the FLEX generator could be hooked up and ready to start recharging the batteries within five hours. Therefore, there was no need for Exelon to extend the battery capacity.

Exelon’s plan assumed that additional backup equipment from the closer of two Regional Response Centers, located nearly one thousand miles away in Memphis, would arrive at Peach Bottom within twenty-four hours. (Exelon contended that it could keep the plant stable forever without any off-site assistance, with repeated torus venting, but conceded that it would be better to eventually have an alternative, less radioactive method.)

Consistent with NEI’s guidance, Exelon’s plan allowed FLEX equipment to be stored below flood level on the assumption that workers would have time to move it to a safer place “prior to the arrival of potentially damaging flood levels.”

As questionable as these timelines are, they don’t take into account the worst case. Exelon found that if a station blackout occurred during refueling, when the entire core of a unit was in the spent fuel pool, there would be no time for the first coping phase at all: FLEX equipment would have to be set up immediately. Exelon asserted that this was not a problem because even though the pool would start to boil after two and a half hours, the spent fuel would not become uncovered until eight hours had elapsed.

The Peach Bottom FLEX plan is a perfect example of the mind-set that led to Fukushima. It represents industry and regulators scripting an accident with little room for improvisation. If a single assumption fails—say, that workers don’t have time to move FLEX equipment to safety in advance of an impending flood—then all the other barriers would collapse like dominoes. Without the FLEX generator, the batteries would fail after five and a half hours and the RCIC could no longer be counted on to cool the reactors. Operators would eventually lose the ability to vent the containment and it would over-pressurize. Backup equipment, located a thousand miles away in Tennessee—and possibly on the other side of massive floodwaters or earthquake destruction—probably would not arrive in time to save the day. Nobody apparently thought those possibilities were worth considering, even after Fukushima Daiichi.

The order also specified that reactor owners must provide “reasonable protection” of the emergency equipment from external events. But what did that mean? The definition was apparently in the eye of the beholder. For instance, the task force had said the equipment should be protected against beyond-design-basis floods, but the commission’s order contained no such requirement.

In any event, by the time the NRC issued the mitigation-strategies order on March 12, 2012, it no longer seemed to matter much. While the NRC commissioners had been ruminating about adequate protection, the industry was creating its own facts on the ground. Plant sites had already ordered or acquired more than three hundred pieces of major equipment under the FLEX voluntary initiative. “Time is of the essence,” said Charles “Chip” Pardee, then head of power generation at Exelon. Arguing that the industry needed to move forward to meet the NRC’s timeline for safety improvements that were still being formulated, Pardee said, “We are proceeding informed by what the NRC is doing, but [we are] out in front of regulations.”

The FLEX approach, however, arguably did not go nearly as far as was needed. For instance, the industry insisted that its purpose was to prevent core damage. Thus, the program did not contemplate how to use such equipment in the highly radioactive and hot environment that would occur after a core started to melt—even though that was one of the greatest challenges at Fukushima. And FLEX was designed with the assumption that a plant’s electrical distribution systems were functional, also at odds with the reality experienced at Fukushima.

The industry’s eagerness to address the lessons of Fukushima even before the NRC could issue requirements was highly ironic at best. After all, plant owners at the same time were dragging their feet—sometimes for decades—on addressing any number of outstanding safety problems, from fire protection to emergency core cooling system blockages. Getting “out in front of regulations” with FLEX was a brilliant move. The more money the industry was spending on equipment that met its own specifications, the more difficult—politically and practically—it would be for the NRC to require substantially different and more robust measures.

The tactic worked. The FLEX program, for all its flaws, did not conflict with the NRC’s ambiguous mitigation strategies order. After many months of deliberation with the NEI on the guidance document it had prepared for the use of FLEX equipment, the NRC largely endorsed NEI’s approach. The tail had wagged the dog.

Over the summer of 2012, the Japanese government solicited views from citizens as it drafted a new energy policy. The results were decisive, noted the survey organizers: “We can say with certainty that a majority of citizens want to achieve a society that does not rely on nuclear power generation.”

Although some believed that the government’s outreach was more appearance than substance, there were signs that the public’s dissatisfaction with the Japanese establishment might be having an impact elsewhere. In September TEPCO announced the creation of an outside review committee to oversee its nuclear operations. With guidance from the committee, TEPCO’s new management hoped to win approval to restart the seven reactors at Kashiwazaki-Kariwa beginning in the spring of 2013, apparently confident that the government’s effort to craft a new energy policy curtailing nuclear power would go nowhere.

On September 14, 2012, the Noda government unveiled its new energy plan, the keystone of which was the elimination of nuclear dependency by the end of the 2030s. The plan was short on specifics. As the Financial Times noted, it was “a somewhat messy compromise that will delight nobody.” It definitely did not delight Japan’s business leaders, who lobbied the Noda government to retain the status quo. “It is highly regrettable that our argument was comprehensively dismissed,” said the head of the powerful business group Keidanren.10

Noda warned that moving toward a nuclear-free Japan would not be easy. “No matter how difficult it is,” he said, “we can no longer put it off.”

It took all of a week before the energy plan was shot full of so many holes that it was barely recognizable.

Noda, like Kan before him, was struggling for political survival. His popularity ratings had not fallen quite as far as Kan’s had a year earlier, but Noda’s party, the Democratic Party of Japan, had an approval rating in the teens. New elections, expected soon, almost certainly would sweep another party and prime minister into office.

Noda’s energy plan originally called for shutting down reactors at the end of their forty-year operating lives and building no new ones. But the day after its release, Yukio Edano, the trade minister, said the ban on new construction would not apply to three reactors already approved for construction. Even more illogically, Japan would continue to pursue its ambitious plan to begin full-scale operation of the Rokkasho Reprocessing Plant, a facility for reprocessing spent nuclear fuel, even though presumably there would be little reactor capacity to dispose of the many tons of plutonium it would produce each year. Operating Rokkasho would increase the massive stockpile of weapon-usable plutonium that Japan had already accumulated, a major security and safety concern.

It seemed that Noda, given the choice of appeasing Japan’s powerful business community or all those people “making lots of noise” on the streets, had opted for the establishment. The backpedaling continued: when the cabinet met on September 19, it sidestepped approving the energy plan, saying only it would “take it into consideration.” The cabinet’s failure to endorse the plan meant that future governments would not be required to follow it. That prompted the Asahi Shimbun to note, “The government’s commitment to abandon nuclear power by the 2030s is increasingly sounding like ‘maybe.’ ”

The cabinet did approve creation of a new nuclear watchdog, the Nuclear Regulation Authority (NRA), after months of political wrangling over the extent of its independence. Even that was cast in doubt when it was reported that most NRA employees had come from the widely discredited NISA and the NSC. The cabinet handed the new agency the unenviable task of deciding whether the nation’s nuclear fleet could safely be restarted. The NRA said the decision could take months. The agency’s rocky start only signaled the tough job it faced in ushering in a new era of nuclear oversight.

The media reported that four of six experts charged with drawing up new safety regulations for the NRA had financial ties to the nuclear industry. (Trying to put the best face on that news, an NRA spokesman noted that the mere fact that the experts had to disclose their personal finances was a positive step.)

In January 2013, the NRA issued a draft set of new safety measures that nuclear plants would have to adopt as a prerequisite for restart. These included upgrades to some of the equipment that had proved inadequate at Fukushima, such as portable power supplies and water sources, so that they would be more reliable in an extended station blackout or other severe accident. Plants would have to show that they could maintain core cooling for a full week without off-site assistance. They would also have to install filtered vents and remote secondary control rooms. In addition, they would have to demonstrate defense against both natural disasters and terrorist attacks, such as a 9/11-style aircraft impact.

The NRA then began a period of “discussion” with the utilities to obtain their views before finalizing the new rules. This was uncharted territory in Japan. It remained to be seen if the NRA would be able to maintain its independence when confronted with predictably intense pressure from the utilities to weaken this stringent and costly set of proposals.

Even as regulators in Japan’s nuclear establishment haggled over details, those whose lives had been disrupted by events at Fukushima Daiichi continued to struggle. For many of them, resuming their normal lives anytime soon seemed unlikely.

A case in point were residents of the “emergency evacuation preparation” zone—a portion of the area between twelve and eighteen miles around the plant. About a month after the accident, the government recommended that vulnerable groups such as children and pregnant women in this zone evacuate, and that all others be ready to flee at a moment’s notice. (In contrast, the highly contaminated area to the northwest of the plant, extending beyond eighteen miles, was a mandatory evacuation zone and remained so.) Nearly half of the 58,000 people in the “evacuation preparation” zone left their homes.

When protective measures were lifted six months later, the evacuees stayed away. Only about 3,100 people had returned as of September 2012. Noticeably absent were young children.

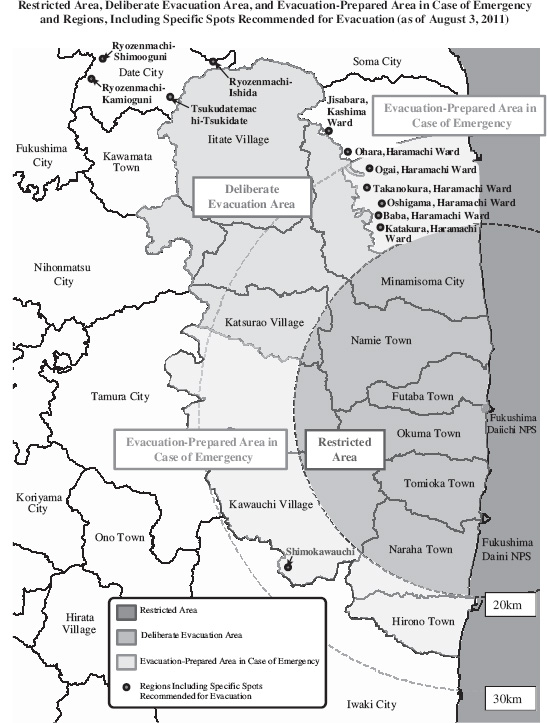

More than a year after the accident, large areas near Fukushima Daiichi remained off-limits. Investigation Committee on the Accident at the Fukushima Nuclear Power Stations of Tokyo Electric Power Company

For residents of the town of Okuma, home to Fukushima Daiichi, the announcement that it would not be safe to return until 2022 was the first blow delivered by the government. Then came word that Tokyo planned to build as many as nine temporary radioactive disposal facilities in Okuma—possible because no one was living there. That spawned fears that even when it was safe to go back, no one would want to. “We have been living there for 1,000 years,” Okuma’s mayor told a reporter.

In October 2012, some of the workers who had risked their lives to wrestle Fukushima Daiichi back from the brink spoke publicly about their experiences for the first time. Until that moment these men had avoided the limelight. Eight of them met with Prime Minister Noda, who was visiting the plant. They began with an apology to the Japanese people.

Six of the workers declined to be identified, or to have their faces shown on camera. “Many [people] view us as the perpetrators,” explained Atsufumi Yoshizawa, who worked with plant superintendent Masao Yoshida during the accident. Uppermost in their minds as the accident unfolded, the men said, was the safety of their fellow workers and of nearby communities, where many of them lived with their families.

They said they had never intended to abandon the plant during the crisis; they knew that erroneous reports to that effect had led to an angry exchange between Prime Minister Kan and TEPCO’s president. “I thought that maybe I would end up not leaving,” Yoshizawa said, “that, as we Japanese say, we would ‘bury our bones’ in that place.”

But the workers stayed despite the terrifying conditions. “I had no intention of dying,” said the operations chief for Units 1 through 4. “Everyone did their best. Dying would have meant giving up.”

Noda returned to Fukushima Prefecture in early December, to kick off the campaign season for the December 16 parliamentary election. Also in Fukushima that day was Shinzo Abe, seeking reelection to the prime minister’s job that he resigned in 2007 after a troubled year in office. For voters across Japan, the slumping economy occupied center stage, and Abe promised change. When the votes were counted, Abe and his conservative-leaning Liberal Democratic Party won by a landslide.

By month’s end, Abe was sworn in as Japan’s seventh prime minister in six and a half years. Among his first promises was a vow to move ahead with new nuclear development.