Graphic Design: The New Basics: Second Edition, Revised and Expanded (2015)

Pattern

The principles discoverable in the works of the past belong to us; not so the results. Owen Jones

The creative evolution of ornament spans all of human history. Shared ways to generate pattern are found in cultures around the world. Universal principles underlie diverse styles and icons that speak to particular times and traditions.

This chapter shows how to build complex patterns around core concepts. Dots, stripes, and grids provide the architecture behind an infinite range of designs. By composing a single element in different schemes, the designer can create endless variations, building complexity around a logical core.

Styles and motifs of pattern-making evolve within and among cultures, and they move in and out of fashion. They travel from place to place and time to time, carried along like viruses by the forces of commerce and the restless desire for variety.

In the twentieth century, modern designers avoided ornate detail in favor of minimal adornment. In 1908, the Viennese design critic Adolf Loos famously conflated “Ornament and Crime.” He linked the human lust for decoration with primitive tattoos and criminal behavior.1

Yet despite the modern distaste for ornament, the structural analysis of pattern is central to modern design theory. In 1856, Owen Jones created his monumental Grammar of Ornament, documenting decorative vocabularies from around the world.2 Jones’s book encouraged Western designers to copy and reinterpret “exotic” motifs from Asia and Africa, but it also helped them recognize principles that unite an endless diversity of forms.

Today, surface pattern is creating a vibrant discourse. The rebirth of ornament is linked to the revival of craft in architecture, products, and interiors, as well as to scientific views of how life emerges from the interaction of simple rules.

The decorative forms presented in this chapter embrace a mix of formal structure and organic irregularity. They meld individual authorship with rule-based systems, and they merge formal abstraction with personal narrative. By understanding how to produce patterns, designers learn how to weave complexity out of elementary structures, participating in the world’s most ancient and prevalent artistic practice.

The secret to success in all ornament is the production of a broad general effect by the repetition of a few simple elements. Owen Jones

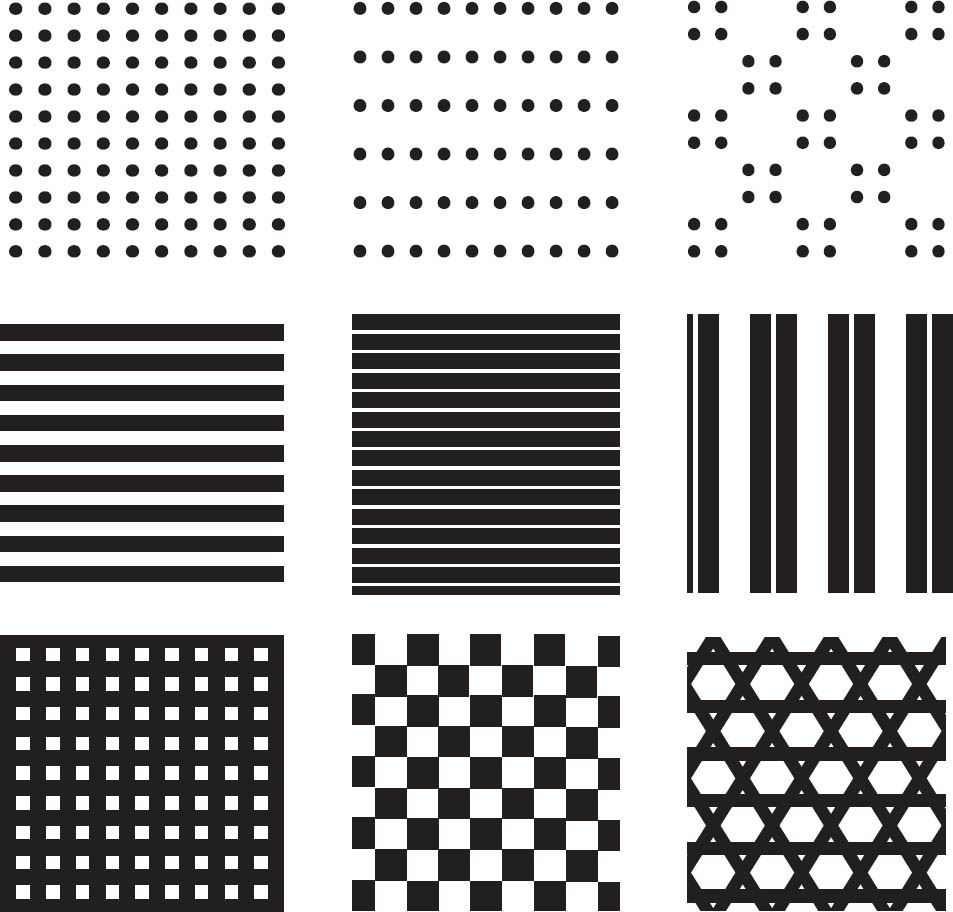

Dots, Stripes, and Grids

In the nineteenth century, designers began analyzing how patterns are made. They found that nearly any pattern arises from three basic forms: isolated elements, linear elements, and the criss-crossing or interaction of the two.1Various terms have been used to name these elementary conditions, but we will call them dots, stripes, and grids.

Any isolated form can be considered a dot, from a simple circle to an ornate flower. A stripe, in contrast, is a linear path. It can consist of a straight, solid line, or it can be built up from smaller elements (dots) that link together visually to form a line.

These two basic structures, dots and stripes, interact to form grids. As a grid takes shape, it subverts the identity of the separate elements in favor of a larger texture. Indeed, creating that larger texture is what pattern design is all about. Imagine a field of wildflowers. It is filled with spectacular individual organisms that contribute to an overall system.

From Point to Line to Grid As dots move together, they form into lines and other shapes (while still being dots). As stripes cross over each other and become grids, they cut up the field into new figures, which function like new dots or new stripes. Some of the most visually fascinating patterns result from figure/ground ambiguity. The identity of a form can oscillate between being a figure (dot, stripe) to being a ground or support for another, opposing figure.

Repeating Elements

How does a simple form—a dot, a square, a flower, a cross—populate a surface to create a pattern that calms, pleases, or surprises us?

Whether rendered by hand, machine, or code, a pattern results from repetition. An army of dots can be regulated by a rigid geometric grid, or it can randomly swarm across a surface via irregular handmade marks. It can spread out in a continuous veil or concentrate its forces in pockets of intensity.

In every instance, however, patterns follow some repetitive principle, whether dictated by a mechanical grid, a digital algorithm, or the physical rhythm of a crafts-person’s tool as it works along a surface.

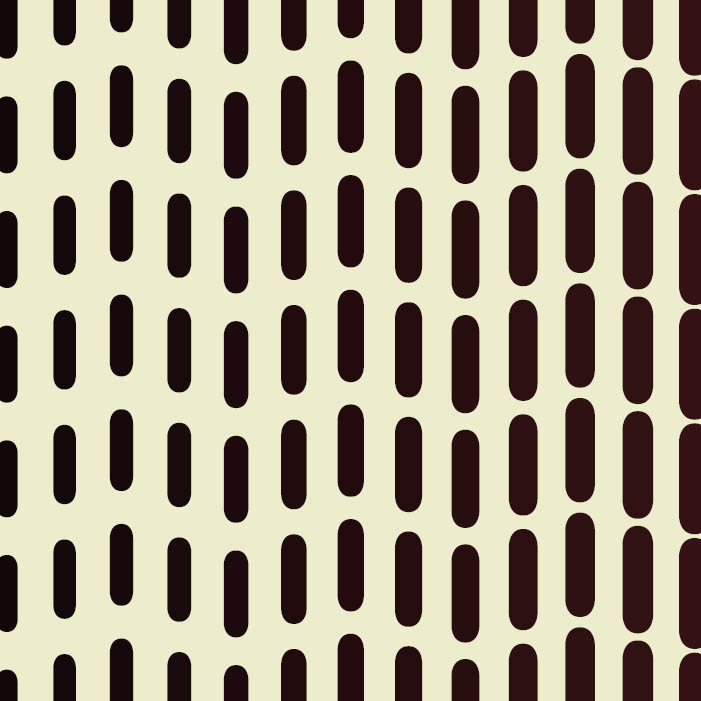

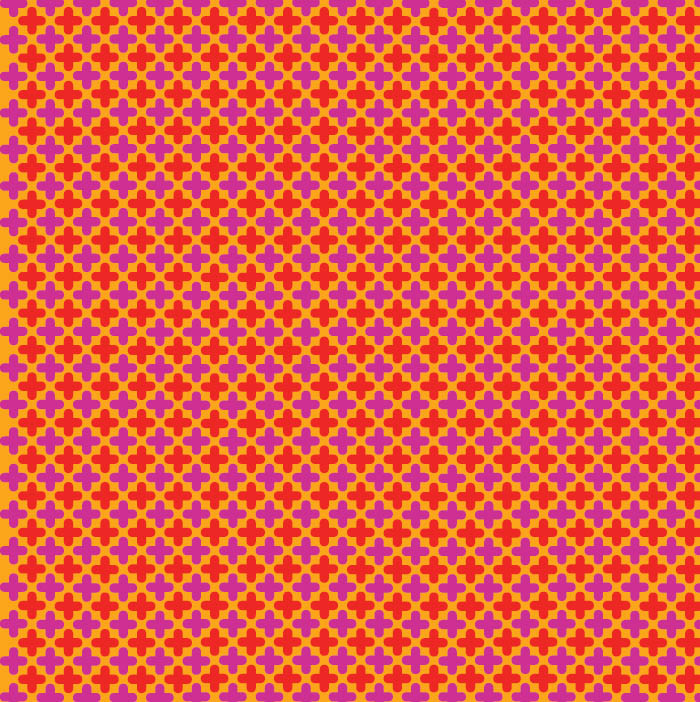

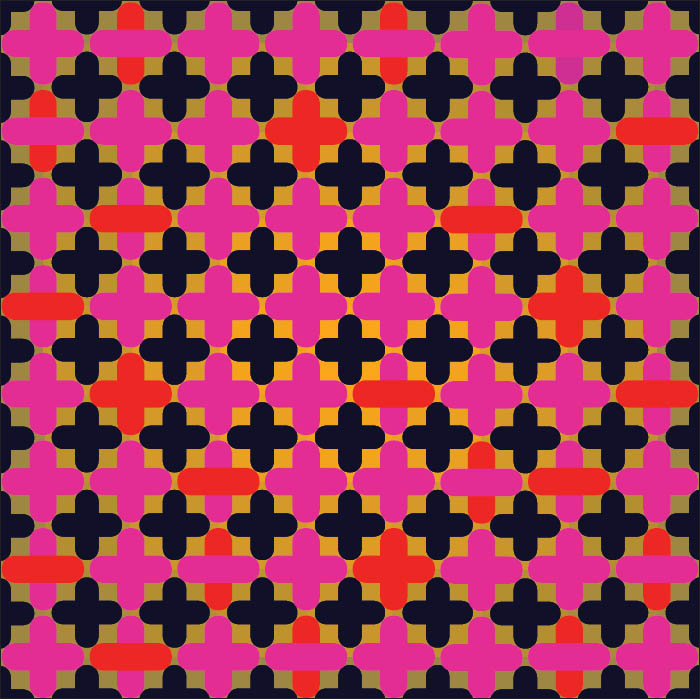

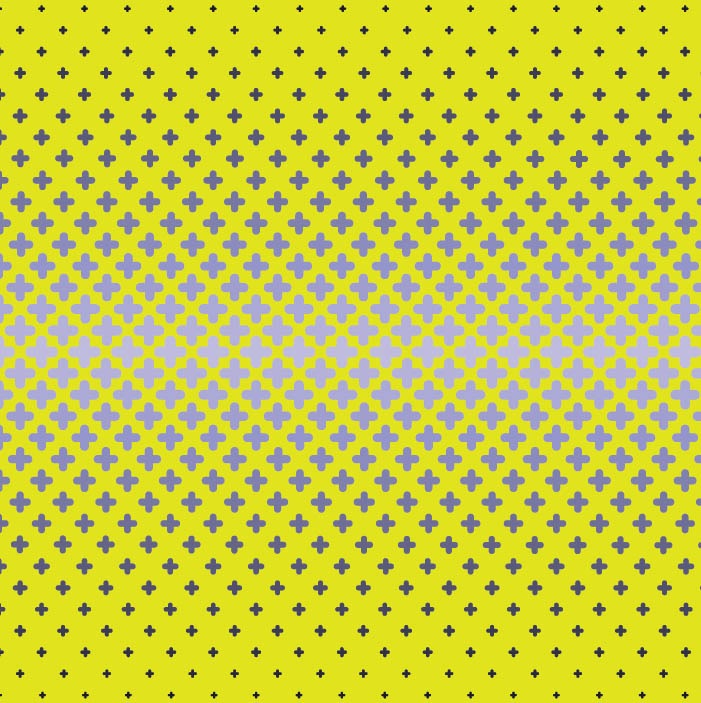

In the series of pattern studies developed here and on the following pages, a simple lozenge form is used to build designs of varying complexity. Experiments of this kind can be performed with countless base shapes, yielding an endless range of individual results.

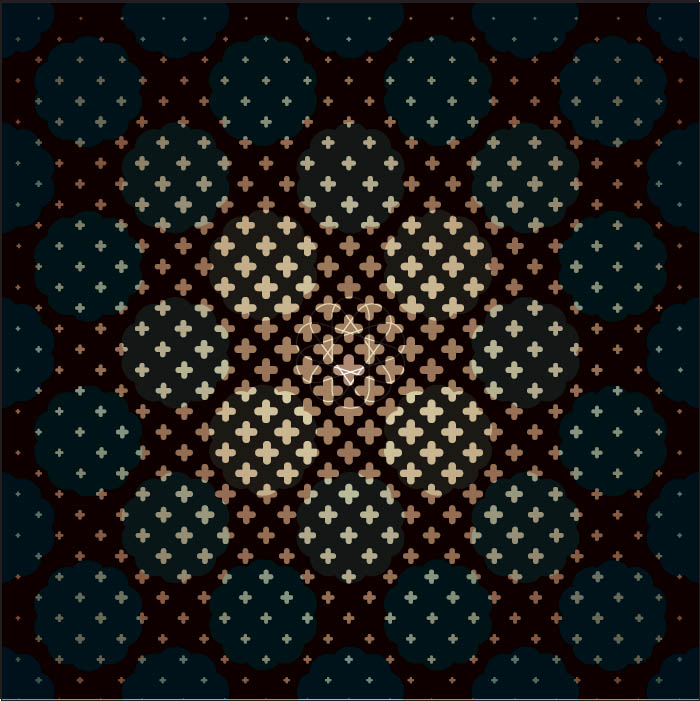

One Element, Many Patterns The basic element in these patterns is a lozenge shape. Based on the orientation, proximity, scale, and color of the lozenges, they group into overlapping lines, forming a nascent grid. Jeremy Botts, MFA Studio.

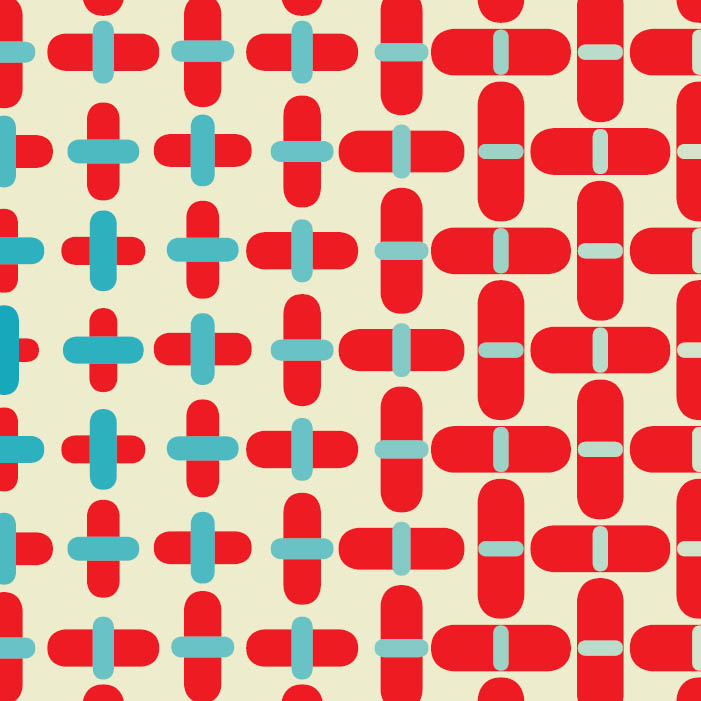

One Element, Many Patterns In this series of designs, the lozenge shape functions as a dot, the primitive element at the core of numerous variations. This oblong dot combines with other dots to form quatrefoils (a new super-dot) as well as lines.

As lozenges of common color or orientation begin to associate with each other visually, additional figures take shape across the surface. Jeremy Botts, MFA Studio.

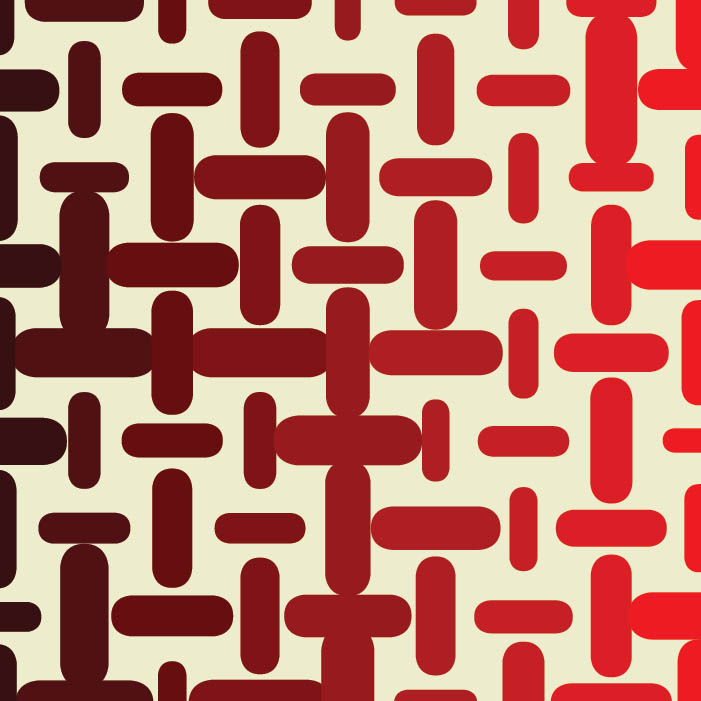

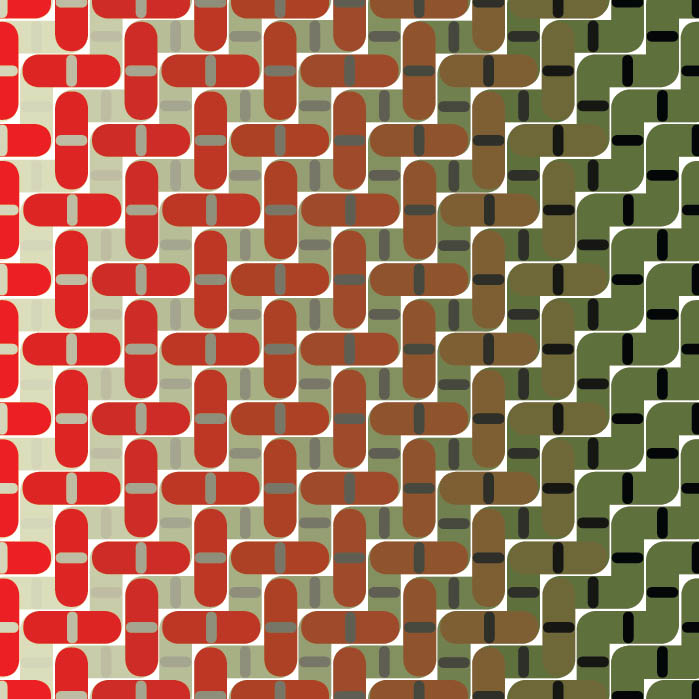

Changing Color, Scale, and Orientation Altering the color contrast between elements or changing the overall scale of the pattern transforms its visual impact. Color shifts can be uniform across the surface, or they can take place in gradients or steps.

Turning elements on an angle or changing their scale also creates a sense of depth and motion. New figures emerge as the lozenge rotates and repeats. Jeremy Botts, MFA Studio.

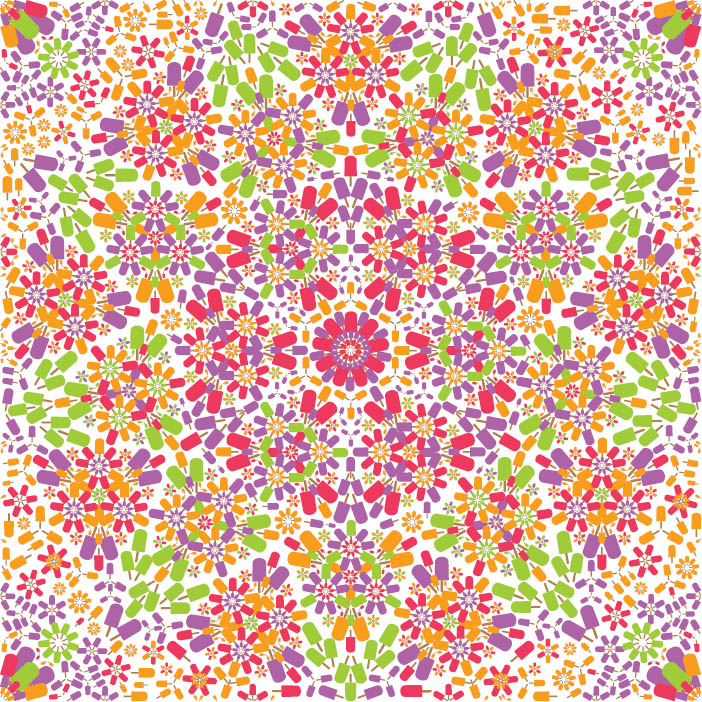

Iconic Patterns Here, traditional pattern structures have been populated with images that have personal significance for the designer: popsicles, bombs, bungee cords, yellow camouflage, and slices of bright green cake. The preceding single tiles can be repeated into larger patterns, as shown following. Spence Holman, MFA Studio.

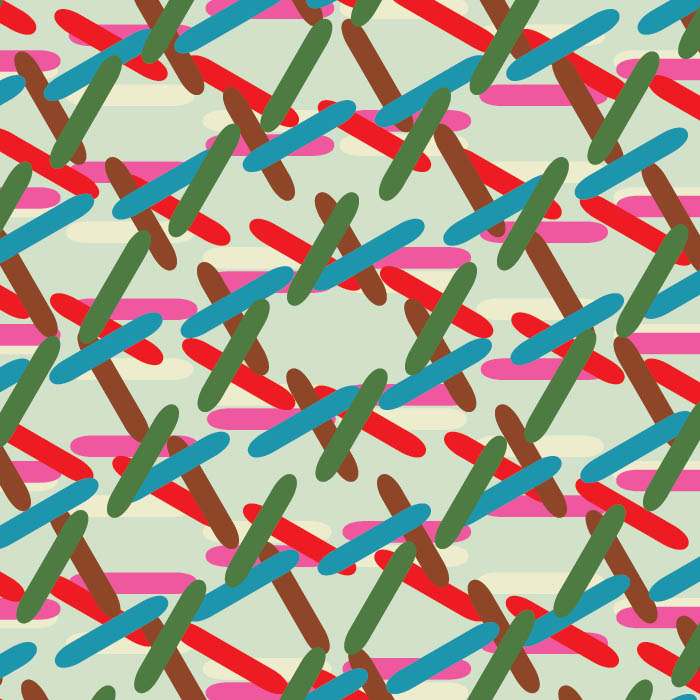

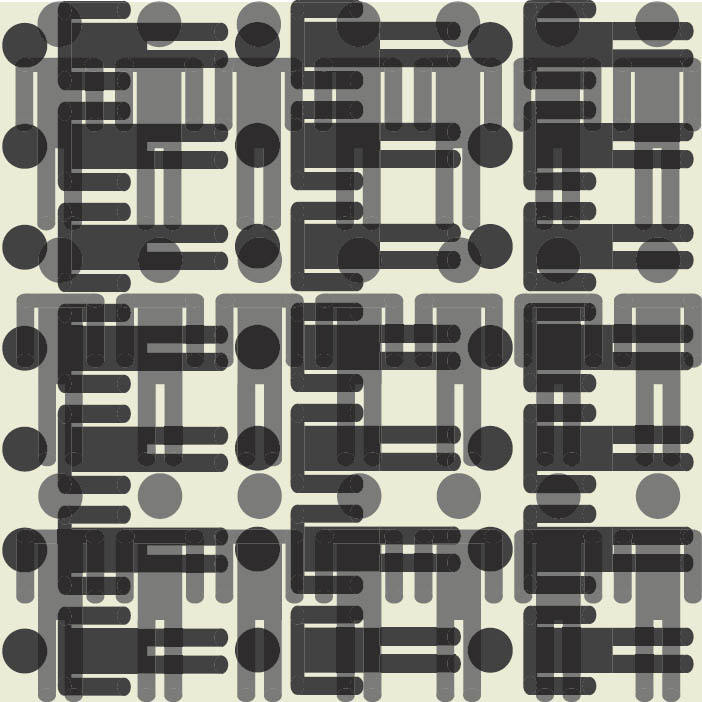

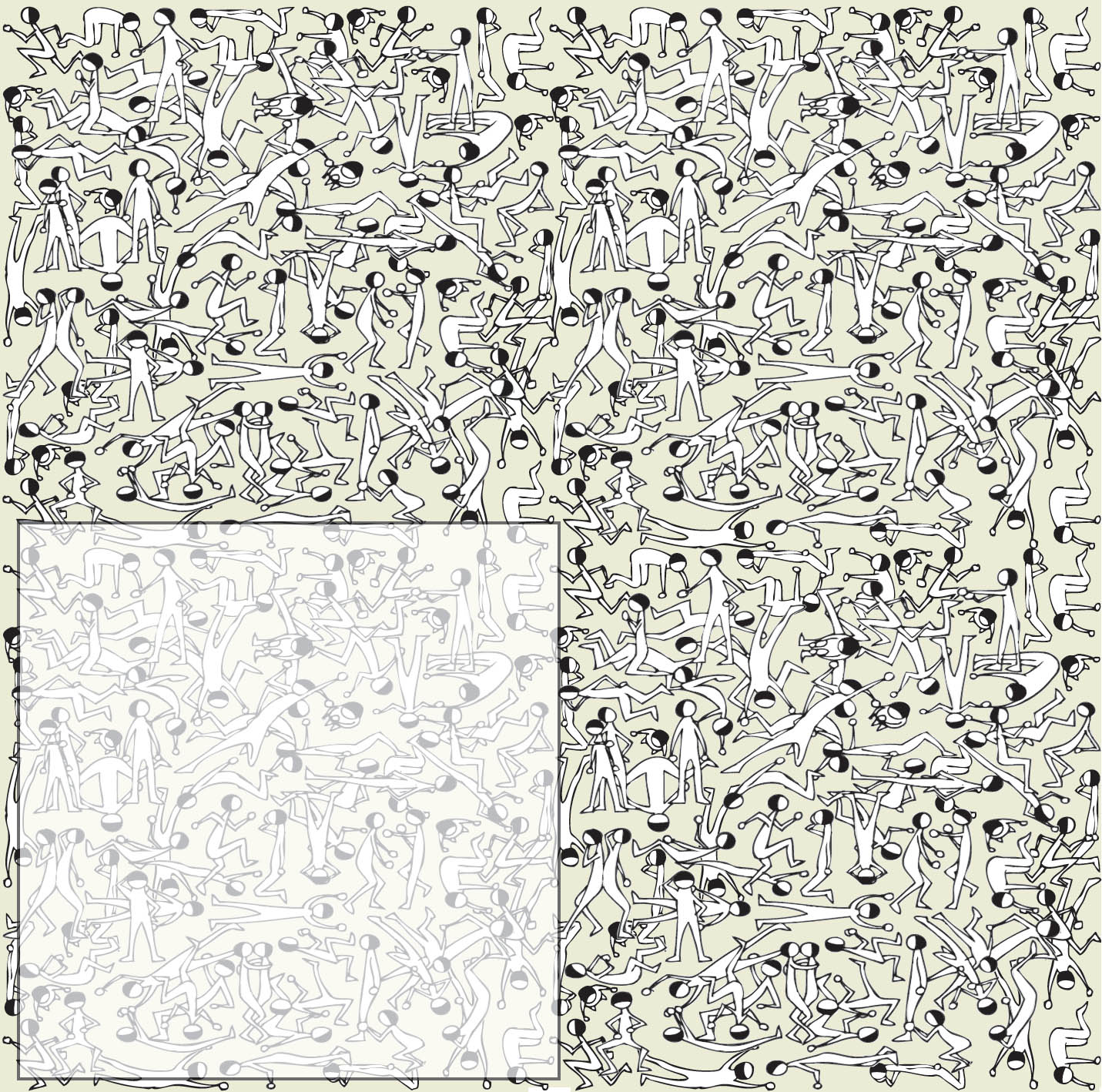

Regular and Irregular Interesting pattern designs often result from a mix of regular and irregular forces as well as abstract and recognizable imagery. Here, regimented rows of icons overlap to create dense crowds as well as orderly battalions. Yong Seuk Lee, MFA Studio.

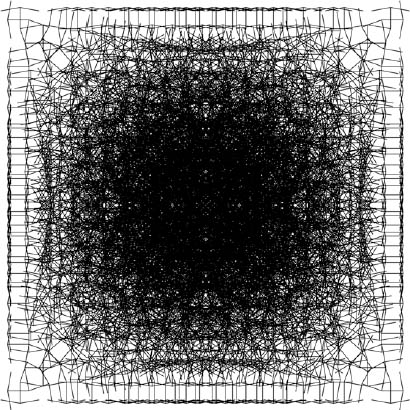

Random Repeat These patterns appear highly irregular, yet they are composed of repeating tiles. To make this kind of pattern, the designer needs to make the left and right edges and the top and bottom edges match up with those of an identical tile. Anything can take place in the middle of the tile. The tiles shown here are square, but they could be rectangles, diamonds, or any other interlocking shape. Yong Seuk Lee, MFA Studio.

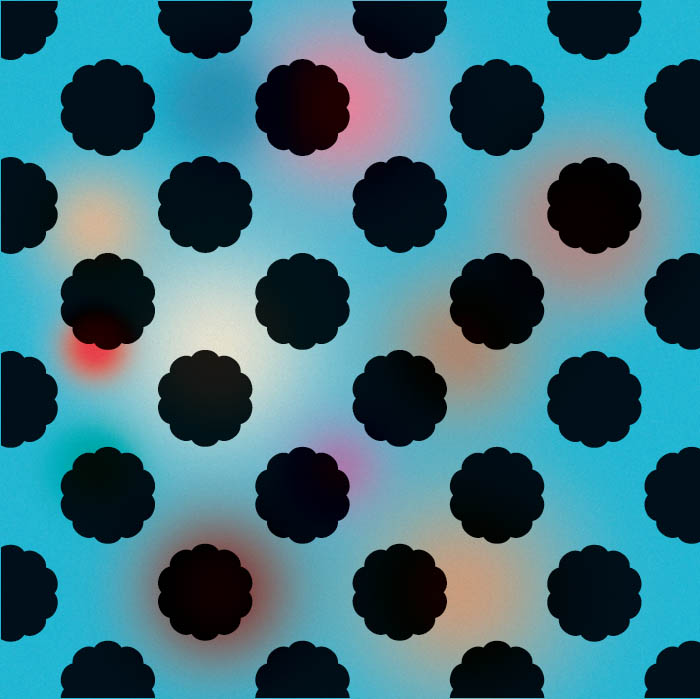

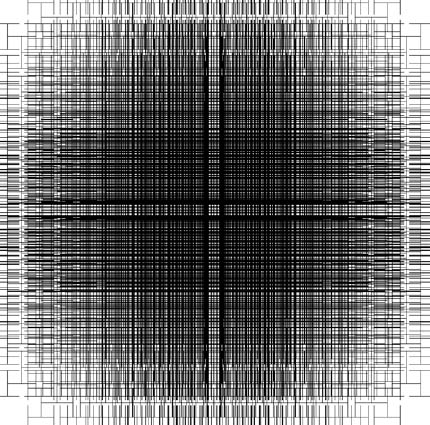

Grid as Matrix An infinite number of patterns can be created from a common grid. In the simplest patterns, each cell is turned on or off. Larger figures take shape as neighboring clusters fill in. More complex patterns occur when the grid serves to locate forms without dictating their outlines or borders. Jason Okutake, MFA Studio.

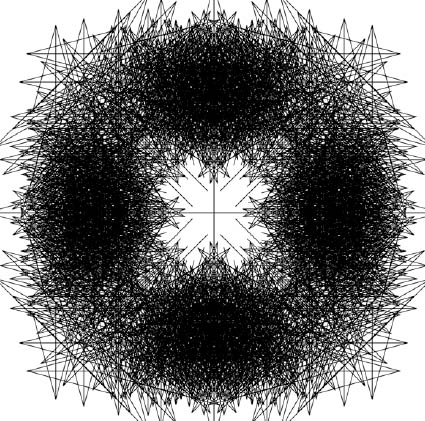

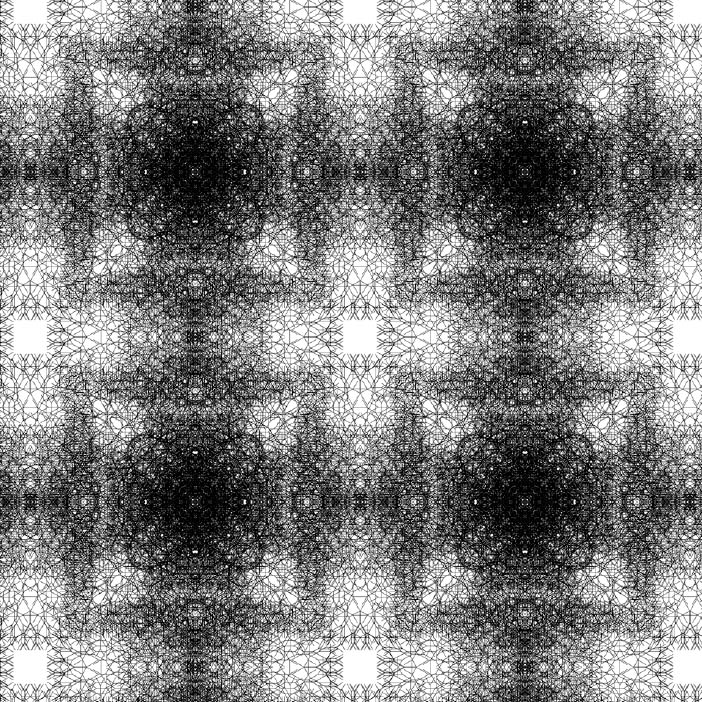

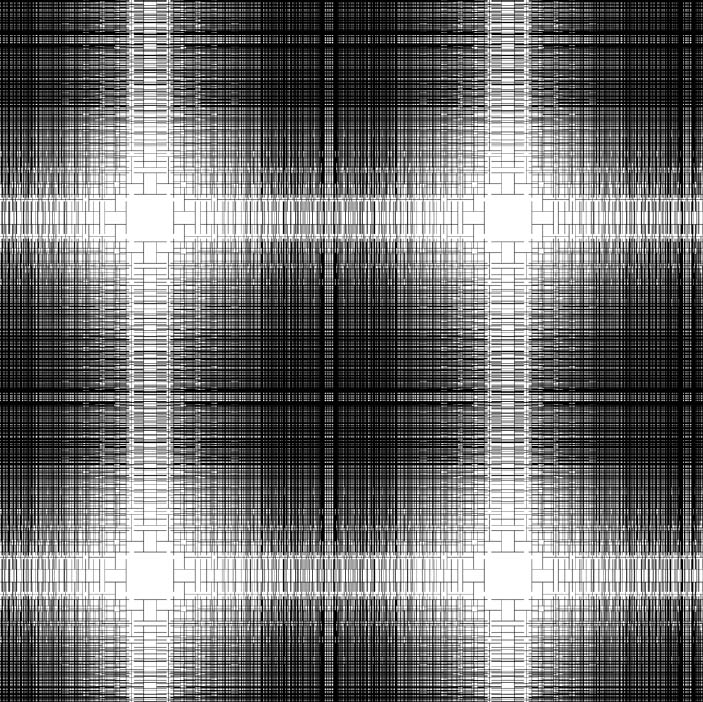

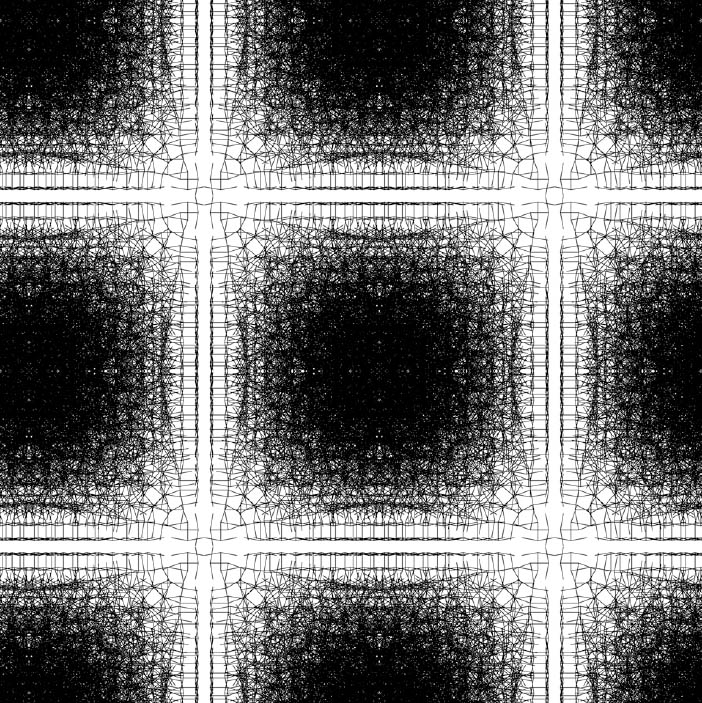

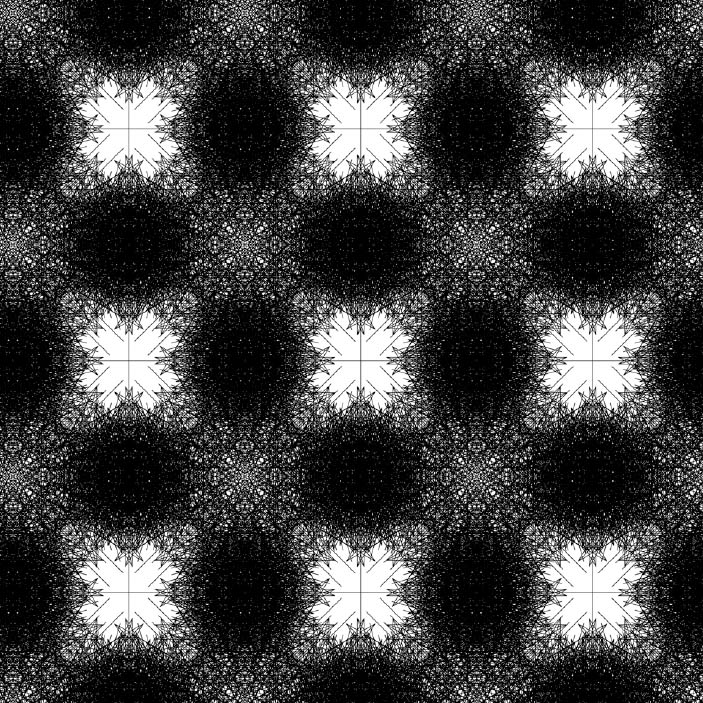

Code-Based Patterns

Every pattern follows a rule. Defining rules with computer code allows the designer to create variations by changing the input to the system. The designer creates the rule, but the end result may be unexpected.

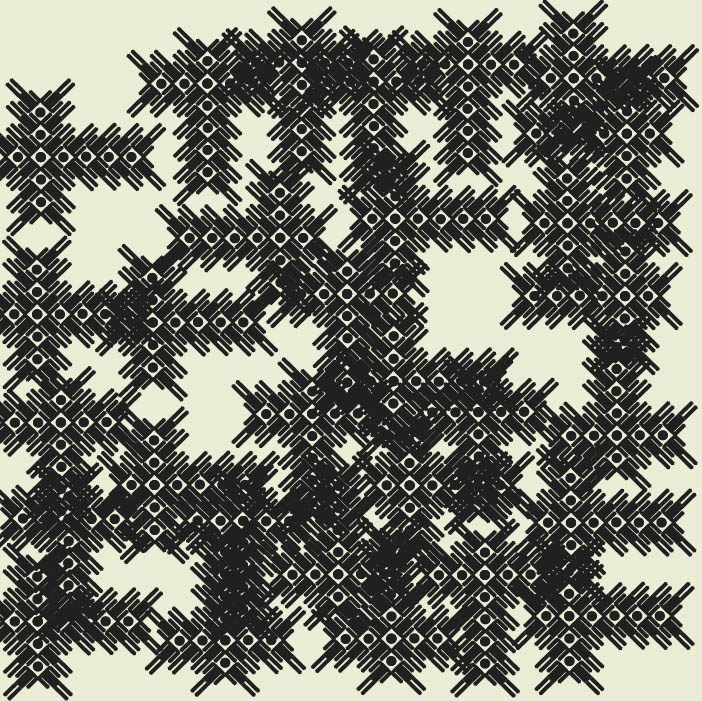

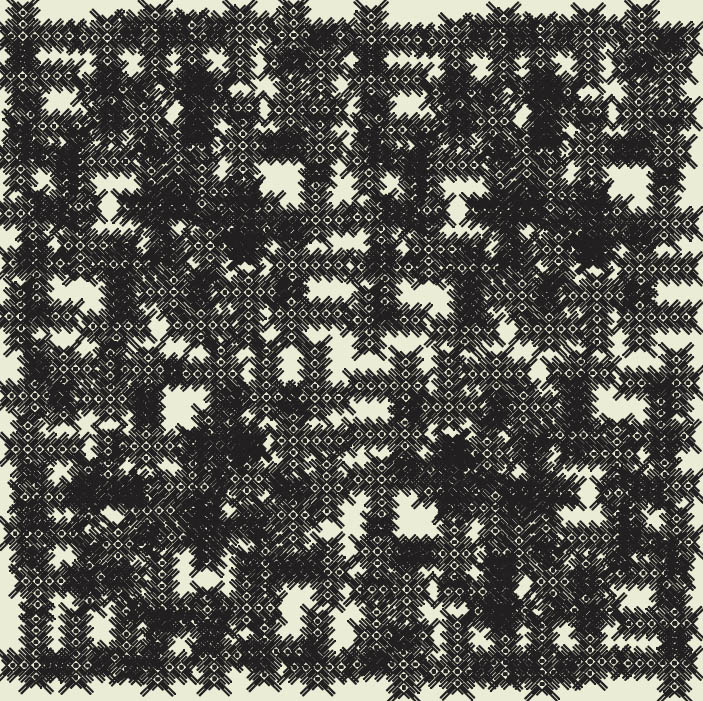

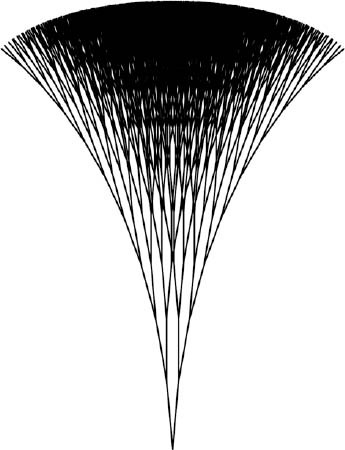

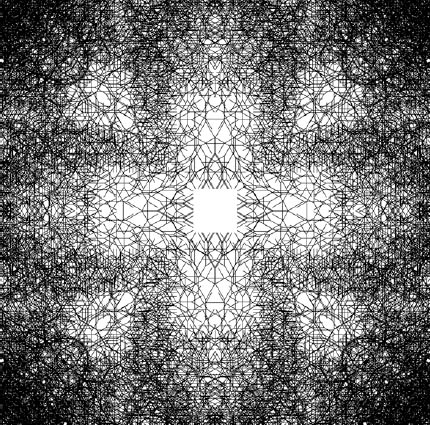

The patterns shown here were designed using Processing, the open-source computer language created for designers and visual artists. All the patterns are built around the basic form of a binary tree, a structure in which every node yields no more than two offspring. New branches appear with each iteration of the program.

The binary tree form has been repeated, rotated, inverted, connected, and overlapped to generate a variety of pattern elements, equivalent to “tiles” in a traditional design. By varying the inputs to the code, the designer created four different tiles, which she joined together in Photoshop to produce a larger repeating pattern. The principle is no different from that used in many traditional ornamental designs, but the process has been automated, yielding a different kind of density.

Vary the Input Four different base elements were created by varying the input to the code. The base “tiles” are joined together to create a repeat pattern; new figures emerge where the tiles come together, just as in traditional ornament. Yeohyun Ahn, Interactive Media II. James Ravel, faculty.

1. Adolf Loos, Ornament and Crime: Selected Essays (Riverside, CA: Ariadne Press, 1998).

2. Owen Jones, The Grammar of Ornament (London: Day and Son, 1856).

1. Our scheme for classifying ornament is adapted from Archibald Christie, Traditional Methods of Pattern Designing; An Introduction to the Study of the Decorative Art (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1910).

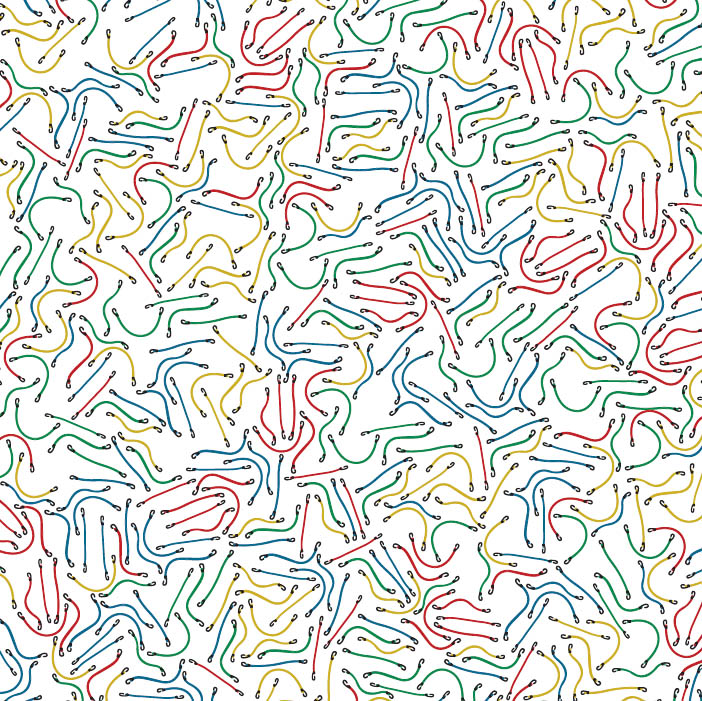

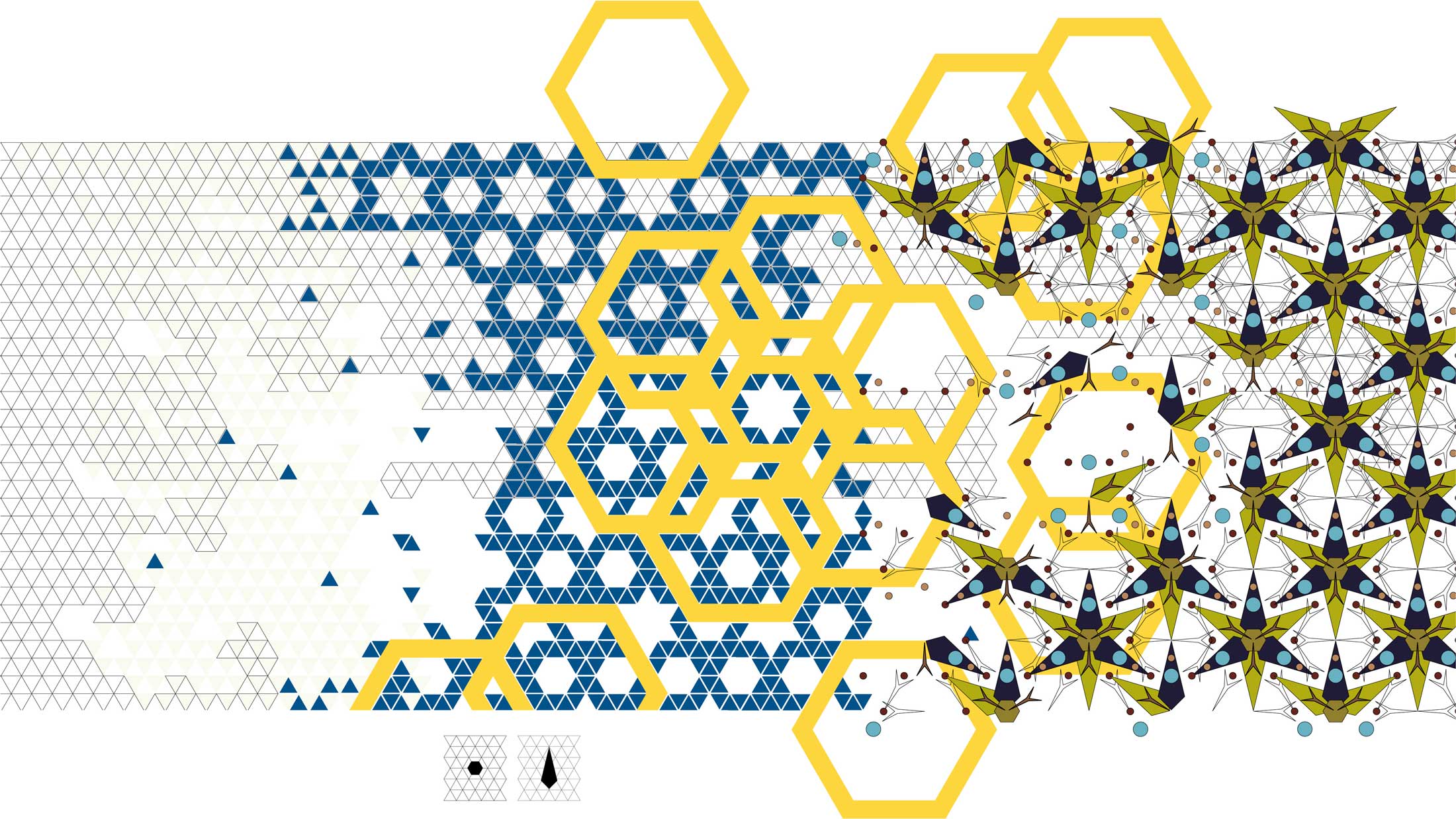

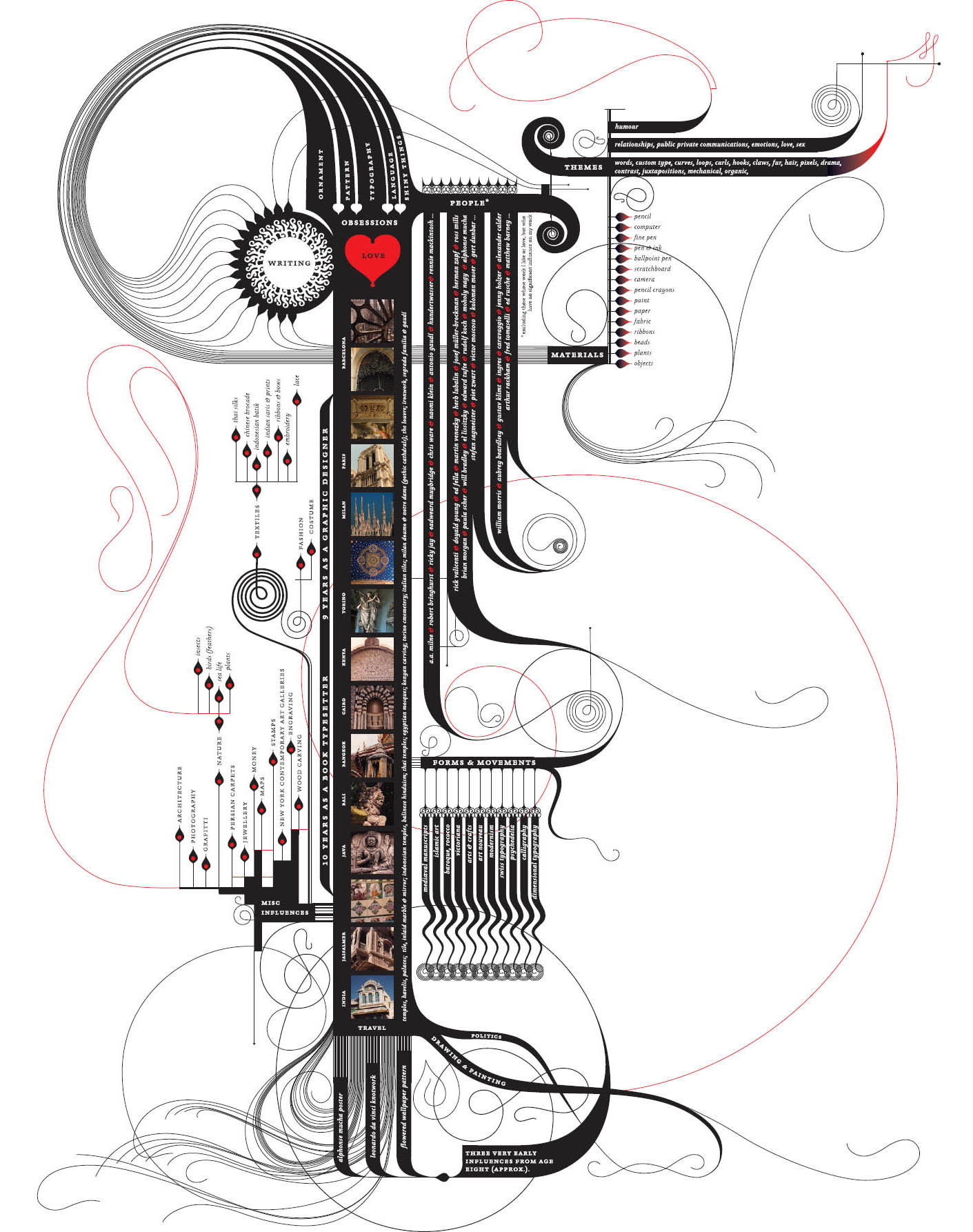

Map of Influences This alluring diagram by designer and artist Marian Bantjes describes her visual influences, which range from medieval and Celtic lettering, to baroque and rococo ornament, to Swiss typography and American psychedelia. Those diverse influences come alive in the flowing, filigreed lines of the piece. Marian Bantjes.