Bookkeeping & Accounting All-in-One For Dummies (2015)

Book V

Accountants: Managing the Business

Chapter 5

Business Budgeting

In This Chapter

![]() Discovering the benefits of budgeting

Discovering the benefits of budgeting

![]() Designing accounting reports for managers

Designing accounting reports for managers

![]() Budgeting in action: developing a profit plan and projecting cash flow from profit

Budgeting in action: developing a profit plan and projecting cash flow from profit

![]() Investing for the long haul

Investing for the long haul

![]() Staying flexible with budgets

Staying flexible with budgets

Abusiness can’t open its doors each day without having some idea of what to expect. And it can’t close its doors at the end of the day not knowing what happened. In the Boy Scouts, the motto is ‘Be Prepared’. Likewise, a business should plan and be prepared for its future, and should control its actual performance to reach its financial goals. The only question is how.

Budgeting is one answer. Please be careful with this term. Budgeting does not refer to putting a financial straitjacket on a business. Instead, business budgeting refers to setting specific goals and having the detailed plans necessary to achieve the goals. Business budgeting is built on realistic forecasts for the coming period, and demands that managers develop a thorough understanding of the profit blueprint of the business as well as the financial effects of the business’s profit-making activities. A business budget is an integrated plan of action - not simply a few trend lines on a financial chart. Business managers have two broad options: they can wait for results to be reported to them on a ‘look back’ basis, or they can look ahead and plan what profit and cash flow should be, and then compare actual results against the plan. Budgeting is the method used to enact this second option.

Budgeting is one answer. Please be careful with this term. Budgeting does not refer to putting a financial straitjacket on a business. Instead, business budgeting refers to setting specific goals and having the detailed plans necessary to achieve the goals. Business budgeting is built on realistic forecasts for the coming period, and demands that managers develop a thorough understanding of the profit blueprint of the business as well as the financial effects of the business’s profit-making activities. A business budget is an integrated plan of action - not simply a few trend lines on a financial chart. Business managers have two broad options: they can wait for results to be reported to them on a ‘look back’ basis, or they can look ahead and plan what profit and cash flow should be, and then compare actual results against the plan. Budgeting is the method used to enact this second option.

The financial statements included in the annual financial report of a business are prepared after the fact; that is, the statements are based on actual transactions that have already taken place. Budgeted financial statements, on the other hand, are prepared before the fact, and are based on future transactions that you expect to take place based on the business’s profit and financial strategy and goals. These forward-looking financial statements are referred to as pro forma, which is Latin for ‘provided in advance’. Note: Budgeted financial statements aren’t reported outside the business; they’re strictly for internal management use.

The financial statements included in the annual financial report of a business are prepared after the fact; that is, the statements are based on actual transactions that have already taken place. Budgeted financial statements, on the other hand, are prepared before the fact, and are based on future transactions that you expect to take place based on the business’s profit and financial strategy and goals. These forward-looking financial statements are referred to as pro forma, which is Latin for ‘provided in advance’. Note: Budgeted financial statements aren’t reported outside the business; they’re strictly for internal management use.

You can see a business’s budget most easily in its set of budgeted financial statements - its budgeted Profit and Loss statement, Balance Sheet and cash flow statement. Preparing these three budgeted financial statements requires a lot of time and effort; managers do detailed analysis to determine how to improve the financial performance of the business. The vigilance required in budgeting helps to maintain and improve profit performance and to plan cash flow.

Budgeting is much more than slap-dashing together a few figures. A budget is an integrated financial plan put down on paper, or these days we should say entered in computer spreadsheets. Planning is the key characteristic of budgeting. The budgeted financial statements encapsulate the financial plan of the business for the coming year.

Budgeting is much more than slap-dashing together a few figures. A budget is an integrated financial plan put down on paper, or these days we should say entered in computer spreadsheets. Planning is the key characteristic of budgeting. The budgeted financial statements encapsulate the financial plan of the business for the coming year.

The Reasons for Budgeting

Managers don’t just look out the window and come up with budget numbers. Budgeting is not pie-in-the-sky, wishful thinking. Business budgeting - to have real value - must start with a critical analysis of the most recent actual performance and position of the business by the managers who are responsible for the results. Then the managers decide on specific and concrete goals for the coming year. Budgets can be done for more than one year, but the key stepping stone into the future is the budget for the coming year - see the sidebar ‘Taking it one game at a time’.

In short, budgeting demands a fair amount of management time and energy. Budgets have to be worth this time and effort. So why should a business go to the trouble of budgeting? Business managers do budgeting and prepare budgeted financial statements for three quite different reasons - distinguishing them from each other is useful.

The modelling reasons for budgeting

To construct budgeted financial statements, you need good models of the profit, cash flow and financial condition of your business. Models are blueprints, or schematics, of how things work. A business budget is, at its core, a financial blueprint of the business.

Note: Don’t be intimidated by the term model. It simply refers to an explicit, condensed description of how profit, cash flow, and assets and liabilities behave. For example, Book V, Chapter 3 presents a model of a management Profit and Loss statement. A model is analytical, but not all models are mathematical. In fact, none of the financial models in this book are the least bit mathematical - but you do have to look at each factor of the model and how it interacts with one or more other factors. The simple accounting equation, assets = liabilities + owners’ equity, is a model of the Balance Sheet, for example. And, as Book V, Chapter 3 explains, profit = contribution margin per unit × units sold in excess of the break-even point.

Note: Don’t be intimidated by the term model. It simply refers to an explicit, condensed description of how profit, cash flow, and assets and liabilities behave. For example, Book V, Chapter 3 presents a model of a management Profit and Loss statement. A model is analytical, but not all models are mathematical. In fact, none of the financial models in this book are the least bit mathematical - but you do have to look at each factor of the model and how it interacts with one or more other factors. The simple accounting equation, assets = liabilities + owners’ equity, is a model of the Balance Sheet, for example. And, as Book V, Chapter 3 explains, profit = contribution margin per unit × units sold in excess of the break-even point.

Taking it one game at a time

A company generally prepares one-year budgets, although many businesses also develop budgets for two, three and five years. However, reaching out beyond a year becomes quite tentative and very iffy. Making forecasts and estimates for the next 12 months is tough enough. A one-year budget is much more definite and detailed in comparison to longer-term budgets. As they say in the sports world, a business should take it one game (or year) at a time.

Looking down the road beyond one year is a good idea, to set long-term goals and to develop long-term strategy. But long-term planning is different to long-term budgeting.

Budgeting relies on financial models, or blueprints, that serve as the foundation for each budgeted financial statement. These blueprints are briefly explained, as follows:

· Budgeted management profit and loss account: Book V, Chapter 3 presents a design for the internal Profit and Loss statement that provides the basic information that managers need for making decisions and exercising control. This internal (for managers only) profit report contains information that isn’t divulged outside the business. The management Profit and Loss statement shown in Figure 3-2 in Book V, Chapter 3 serves as a hands-on profit model - one that highlights the critical variables that drive profit. This management Profit and Loss statement separates variable and fixed expenses and includes sales volume, contribution margin per unit and other factors that determine profit performance. The management Profit and Loss statement is like a schematic that shows the path to the bottom line. It reveals the factors that must be improved in order to improve profit performance in the coming period.

· Budgeted Balance Sheet: The key connections and ratios between sales revenue and expenses and their related assets and liabilities are the elements of the basic model for the budgeted Balance Sheet.

· Budgeted cash flow statement: The changes in assets and liabilities from their balances at the end of the year just concluded and the balances at the end of the coming year determine cash flow from profit for the coming year. These changes constitute the basic model of cash flow from profit, which Book IV, Chapter 3 explains (a comparative Balance Sheet, which can be used to provide information for the cash flow statement, can be found in the ‘Have a Go’ section). The other sources and uses of cash depend on managers’ strategic decisions regarding capital expenditures that will be made during the coming year, and how much new capital will be raised by increased debt and from owners’ additional investment of capital in the business.

In short, budgeting requires good working models of profit performance, financial condition (assets and liabilities) and cash flow from profit. Constructing good budgets is a strong incentive for businesses to develop financial models that not only help in the budgeting process but also help managers make day-to-day decisions.

In short, budgeting requires good working models of profit performance, financial condition (assets and liabilities) and cash flow from profit. Constructing good budgets is a strong incentive for businesses to develop financial models that not only help in the budgeting process but also help managers make day-to-day decisions.

Planning reasons for budgeting

One main purpose of budgeting is to develop a definite and detailed financial plan for the coming period. To do budgeting, managers have to establish explicit financial objectives for the coming year and identify exactly what has to be done to accomplish these financial objectives. Budgeted financial statements and their supporting schedules provide clear destination points - the financial flight plan for a business.

The process of putting together a budget directs attention to the specific things that you must do to achieve your profit objectives and to optimise your assets and capital requirements. Basically, budgets are a form of planning, and planning pushes managers to answer the question: ‘How are we going to get there from here?’

Budgeting also has other planning-related benefits:

· Budgeting encourages a business to articulate its vision, strategy and goals. A business needs a clearly-stated strategy guided by an overarching vision, and should have definite and explicit goals. It’s not enough for business managers to have strategy and goals in their heads - and nowhere else. Developing budgeted financial statements forces managers to be explicit and definite about the objectives of the business, and to formulate realistic plans for achieving the business objectives.

· Budgeting imposes discipline and deadlines on the planning process. Many busy managers have trouble finding enough time for lunch, let alone planning for the upcoming financial period. Budgeting pushes managers to set aside time to prepare a detailed plan that serves as a road map for the business. Good planning results in a concrete course of action that details how a company plans to achieve its financial objectives.

Management control reasons for budgeting

Budgets can be and usually are used as a means of management control, which involves comparing budgets against actual performance and holding individual managers responsible for keeping the business on schedule in reaching its financial objectives. The board of directors of a corporation focus their attention on the master budget for the whole business: the budgeted management Profit and Loss statement, the budgeted Balance Sheet and the budgeted cash flow statement for the coming year.

The chief executive officer and the chairman of the business focus on the master budget. They also look at how each manager in the organisation is doing on his part of the master budget. As you move down the organisation chart of a business, managers have narrower responsibilities - say, for the business’s north-eastern territory or for one major product line; therefore, the master budget is broken down into parts that follow the business’s organisational structure. In other words, the master budget is put together from many pieces, one for each separate organisational unit of the business. So, for example, the manager of one of the company’s far-flung warehouses has a separate budget for expenses and stock levels for his area.

By using budget targets as benchmarks against which actual performance is compared, managers can closely monitor progress toward (or deviations from) the budget goals and timetable. You use a budget plan like a navigation chart to keep your business on course. Significant variations from budget raise red flags, in which case you can determine that performance is off course or that the budget needs to be revised because of unexpected developments.

For management control, the annual budgeted management Profit and Loss statement is divided into months or quarters. The budgeted Balance Sheet and budgeted cash flow statement are also put on a monthly or quarterly basis. The business should not wait too long to compare budgeted sales revenue and expenses against actual performance (or to compare actual cash flows and asset levels against the budget timetable). You need to take prompt action when problems arise, such as a divergence between budgeted expenses and actual expenses. Profit is the main thing to pay attention to, but debtors and stock can get out of control (become too high relative to actual sales revenue and cost of goods sold expense), causing cash flow problems. (Book IV, Chapter 3 explains how increases in debtors and stock are negative factors on cash flow from profit.) A business can’t afford to ignore its Balance Sheet and cash flow numbers until the end of the year.

For management control, the annual budgeted management Profit and Loss statement is divided into months or quarters. The budgeted Balance Sheet and budgeted cash flow statement are also put on a monthly or quarterly basis. The business should not wait too long to compare budgeted sales revenue and expenses against actual performance (or to compare actual cash flows and asset levels against the budget timetable). You need to take prompt action when problems arise, such as a divergence between budgeted expenses and actual expenses. Profit is the main thing to pay attention to, but debtors and stock can get out of control (become too high relative to actual sales revenue and cost of goods sold expense), causing cash flow problems. (Book IV, Chapter 3 explains how increases in debtors and stock are negative factors on cash flow from profit.) A business can’t afford to ignore its Balance Sheet and cash flow numbers until the end of the year.

Other benefits of budgeting

Budgeting has advantages and ramifications that go beyond the financial dimension and have more to do with business management in general. These points are briefly discussed as follows:

· Budgeting forces managers to do better forecasting. Managers should constantly scan the business environment to identify sea changes that can impact the business. Vague generalisations about what the future might hold for the business aren’t quite good enough for assembling a budget. Managers are forced to put their predictions into definite and concrete forecasts.

· Budgeting motivates managers and employees by providing useful yardsticks for evaluating performance and for setting managers’ compensation when goals are achieved. The budgeting process can have a good motivational impact on employees and managers by involving managers in the budgeting process (especially in setting goals and objectives) and by providing incentives to managers to strive for and achieve the business’s goals and objectives. Budgets can be used to reward good results. Budgets provide useful information for superiors to evaluate the performance of managers. Budgets supply baseline financial information for incentive compensation plans. The profit plan (budget) for the year can be used to award year-end bonuses according to whether designated goals are achieved.

· Budgeting is essential in writing a business plan. New and emerging businesses must present a convincing business plan when raising capital. Because these businesses may have little or no history, the managers and owners of a small business must demonstrate convincingly that the company has a clear strategy and a realistic plan to make money. A coherent, realistic budget forecast is an essential component of a business plan. Venture capital sources definitely want to see the budgeted financial statements of the business.

In larger businesses, budgets are typically used to hold managers accountable for their areas of responsibility in the organisation; actual results are compared against budgeted goals and timetables, and variances are highlighted. Managers don’t mind taking credit for favourable variances, or when actual comes in better than budget. Beating the budget for the period, after all, calls attention to outstanding performance. But unfavourable variances are a different matter. If the manager’s budgeted goals and targets are fair and reasonable, the manager should carefully analyse what went wrong and what needs to be improved. But if the manager perceives the budgeted goals and targets to be arbitrarily imposed by superiors and not realistic, serious motivational problems can arise.

In reviewing the performance of their subordinates, managers should handle unfavourable variances very carefully. Stern action may be called for, but managers should recognise that the budget benchmarks may not be entirely fair, and should make allowances for unexpected developments that occur after the budget goals and targets are established.

In reviewing the performance of their subordinates, managers should handle unfavourable variances very carefully. Stern action may be called for, but managers should recognise that the budget benchmarks may not be entirely fair, and should make allowances for unexpected developments that occur after the budget goals and targets are established.

Budgeting and Management Accounting

What we say earlier in the chapter can be likened to an advertisement for budgeting - emphasising the reasons for and advantages of budgeting by a business. So every business does budgeting, right? Nope. Smaller businesses generally do little or no budgeting - and even many larger businesses avoid budgeting. The reasons are many, and mostly practical in nature.

Some businesses are in relatively mature stages of their life cycle or operate in an industry that is mature and stable. These companies don’t have to plan for any major changes or discontinuities. Next year will be a great deal like last year. The benefits of going through a formal budgeting process don’t seem worth the time and cost to them. At the other extreme, a business may be in a very uncertain environment; attempting to predict the future seems pointless. A business may lack the expertise and experience to prepare budgeted financial statements, and it may not be willing to pay the cost for an accountant or outside consultant to help.

Every business - whether it does budgeting or not - should design internal accounting reports that provide the information managers need to control the business. Obviously, managers should keep close tabs on what’s going on throughout the business. A business may not do any budgeting, and thus it doesn’t prepare budgeted financial statements. But its managers should receive regular Profit and Loss statements, Balance Sheets and cash flow statements - and these key internal financial statements should contain detailed management control information. Other specialised accounting reports may be needed as well.

Every business - whether it does budgeting or not - should design internal accounting reports that provide the information managers need to control the business. Obviously, managers should keep close tabs on what’s going on throughout the business. A business may not do any budgeting, and thus it doesn’t prepare budgeted financial statements. But its managers should receive regular Profit and Loss statements, Balance Sheets and cash flow statements - and these key internal financial statements should contain detailed management control information. Other specialised accounting reports may be needed as well.

Most business managers, in our experience, would tell you that the accounting reports they get are reasonably good for management control. Their accounting reports provide the detailed information they need for keeping a close watch on the thousand and one details about the business (or their particular sphere of responsibility in the business organisation). Their main criticisms are that too much information is reported to them and all the information is flat, as if all the information is equally relevant. Managers are very busy people, and have only so much time to read the accounting reports coming to them. Managers have a valid beef on this score, we think. Ideally, significant deviations and problems should be highlighted in the accounting reports they receive - but separating the important from the not-so-important is easier said than done.

If you were to ask a cross-section of business managers how useful their accounting reports are for making decisions, you would get a different answer than how good the accounting reports are for management control. Business managers make many decisions affecting profit: setting sales prices, buying products, determining wages and salaries, hiring independent contractors and purchasing fixed assets are just a few that come to mind. Managers should carefully analyse how their actions would impact profit before reaching final decisions. Managers need internal Profit and Loss statements that are good profit models - that make clear the critical variables that affect profit (see Figure 3-2 in Book V, Chapter 3 for an example). Well-designed management Profit and Loss statements are absolutely essential for helping managers make good decisions.

Keep in mind that almost all business decisions involve non-financial and non-quantifiable factors that go beyond the information included in management accounting reports. For example, the accounting department of a business can calculate the cost savings of a wage cut, or the elimination of overtime hours by employees, or a change in the retirement plan for employees - and the manager would certainly look at this data. But such decisions must consider many other factors such as effects on employee morale and productivity, the possibility of the union going out on strike, legal issues and so on. In short, accounting reports provide only part of the information needed for business decisions, though an essential part for sure.

Needless to say, the internal accounting reports to managers should be clear and straightforward. The manner of presentation and means of communication should be attention getting. A manager shouldn’t have to call the accounting department for an explanation. Designing management accounting reports is a separate topic - one beyond the limits of this book.

In the absence of budgeting by a business, the internal accounting reports to its managers become the major - often the only - regular source of financial information to them. Without budgeting, the internal accounting reports have to serve a dual function - both for control and for planning. The managers use the accounting reports to critically review what’s happened (control), and use the information in the reports to make decisions for the future (planning).

Before leaving the topic, we have one final observation to share with you. Many management accounting reports that we’ve seen could be improved. Accounting systems, unfortunately, give so much attention to the demands of preparing external financial statements and tax returns that the needs managers have for good internal reports are too often overlooked or ignored. The accounting reports in many businesses don’t speak to the managers receiving them - the reports are too voluminous and technical, and aren’t focused on the most urgent and important problems facing the managers. Designing good internal accounting reports for managers is a demanding task, to be sure. Every business should take a hard look at its internal management accounting reports and identify what needs to be improved.

Budgeting in Action

Suppose you’re the general manager of one of a large company’s several divisions. You have broad authority to run this division, as well as the responsibility for meeting the financial expectations for your division. To be more specific, your profit responsibility is to produce a satisfactory annual operating profit, or earnings before interest and tax (EBIT). (Interest and tax expenses are handled at a higher level in the organisation.)

Suppose you’re the general manager of one of a large company’s several divisions. You have broad authority to run this division, as well as the responsibility for meeting the financial expectations for your division. To be more specific, your profit responsibility is to produce a satisfactory annual operating profit, or earnings before interest and tax (EBIT). (Interest and tax expenses are handled at a higher level in the organisation.)

The CEO has made clear to you that he expects your division to increase EBIT during the coming year by about 10 per cent (£256,000, to be exact). In fact, he’s asked you to prepare a budgeted management Profit and Loss statement showing your plan for increasing your division’s EBIT by this target amount. He’s also asked you to prepare a budgeted cash flow from profit based on your profit plan for the coming year.

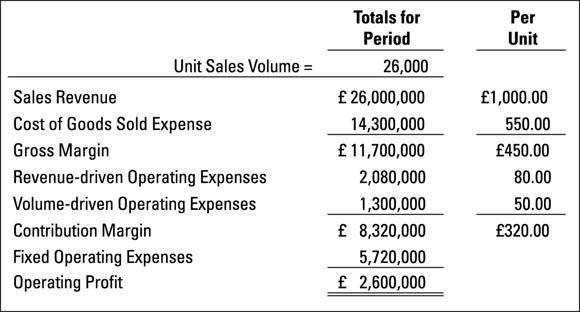

Figure 5-1 presents the management Profit and Loss statement of your division for the year just ended. The format of this accounting report follows the profit model discussed in Book V, Chapter 3, which explains profit behaviour and how to increase profit. Note that fixed operating expenses are separated from the two variable operating expenses. To simplify the discussion, we’ve significantly condensed your management Profit and Loss statement. (Your actual reports would include much more detailed information about sales and expenses.) Also, we assume that you sell only one product, to keep the number crunching to a minimum.

Figure 5-1: Management Profit and Loss statement for year just ended.

Most businesses, or the major divisions of a large business, sell a mix of several different products. General Motors, for example, sells many different makes and models of cars and commercial vehicles, to say nothing about its other products. The next time you visit your local hardware store, look at the number of products on the shelves. The assortment of products sold by a business and the quantities sold of each that make up its total sales revenue is referred to as its sales mix. As a general rule, certain products have higher profit margins than others. Some products may have extremely low profit margins; these are called loss leaders. The marketing strategy for loss leaders is to use them as magnets to get customers to buy your higher-profit-margin products along with their purchase of the loss leaders. Shifting the sales mix to a higher proportion of higher-profit-margin products has the effect of increasing the average profit margin on all products sold. (A shift to lower-profit-margin products would have the opposite effect, of course.) Budgeting sales revenue and expenses for the coming year must include any planned shifts in the company’s sales mix.

Most businesses, or the major divisions of a large business, sell a mix of several different products. General Motors, for example, sells many different makes and models of cars and commercial vehicles, to say nothing about its other products. The next time you visit your local hardware store, look at the number of products on the shelves. The assortment of products sold by a business and the quantities sold of each that make up its total sales revenue is referred to as its sales mix. As a general rule, certain products have higher profit margins than others. Some products may have extremely low profit margins; these are called loss leaders. The marketing strategy for loss leaders is to use them as magnets to get customers to buy your higher-profit-margin products along with their purchase of the loss leaders. Shifting the sales mix to a higher proportion of higher-profit-margin products has the effect of increasing the average profit margin on all products sold. (A shift to lower-profit-margin products would have the opposite effect, of course.) Budgeting sales revenue and expenses for the coming year must include any planned shifts in the company’s sales mix.

Developing your profit strategy and budgeted Profit and Loss statement

Suppose that you and your managers, with the assistance of your accounting staff, have analysed your fixed operating expenses line by line for the coming year. Some of these fixed expenses will actually be reduced or eliminated next year. But the large majority of these costs will continue next year, and most are subject to inflation. Based on careful studies and estimates, you and your staff forecast that your total fixed operating expenses for next year will be £6,006,000 (including £835,000 depreciation expense, compared with the £780,000 depreciation expense for last year).

Thus, you will need to earn £8,862,000 total contribution margin next year:

|

£2,856,000 |

EBIT goal (£2,600,000 last year plus £256,000 budgeted increase) |

|

+ 6,006,000 |

Budgeted fixed operating expenses next year |

|

£8,862,000 |

Total contribution margin goal next year |

This is your main profit budget goal for next year, assuming that fixed operating expenses are kept in line. Fortunately, your volume-driven variable operating expenses shouldn’t increase next year. These are mainly transportation costs, and the shipping industry is in a very competitive ‘hold-the-price-down’ mode of operations that should last through the coming year. The cost per unit shipped shouldn’t increase, but if you sell and ship more units next year, the expense will increase in proportion.

You’ve decided to hold the revenue-driven operating expenses at 8 per cent of sales revenue during the coming year, the same as for the year just ended. These are sales commissions, and you’ve already announced to your sales staff that their sales commission percentage will remain the same during the coming year. On the other hand, your purchasing manager has told you to plan on a 4 per cent product cost increase next year - from £550 per unit to £572 per unit, or an increase of £22 per unit. Thus, your unit contribution margin would drop from £320 to £298 (if the other factors that determine margin remain the same).

One way to attempt to achieve your total contribution margin objective next year is to load all the needed increase on sales volume and keep sales price the same. (We’re not suggesting that this strategy is a good one, but it’s a good point of departure.) At the lower unit contribution margin, your sales volume next year would have to be 29,738 units:

· £8,862,000 total contribution margin goal ÷ £298 contribution margin per unit = 29,738 units sales volume

Compared with last year’s 26,000 units sales volume, you would have to increase your sales by over 14 per cent. This may not be feasible.

After discussing this scenario with your sales manager, you conclude that sales volume can’t be increased by 14 per cent. You’ll have to raise the sales price to provide part of the needed increase in total contribution margin and to offset the increase in product cost. After much discussion, you and your sales manager decide to increase the sales price by 3 per cent. Based on the 3 per cent sales price increase and the 4 per cent product cost increase, your unit contribution margin next year is determined as follows:

|

£2,856,000 |

EBIT goal (£2,600,000 last year plus £256,000 budgeted increase) |

|

+ 6,006,000 |

Budgeted fixed operating expenses next year |

|

£8,862,000 |

Total contribution margin goal next year |

At this £325.60 budgeted contribution margin per unit, you determine the total sales volume needed next year to reach your profit goal as follows:

· £8,862,000 total contribution margin goal next year ÷ £325.60 contribution margin per unit = 27,217 units sales volume

This sales volume is about 5 per cent higher than last year (1,217 additional units over the 26,000 sales volume last year = about 5 per cent increase).

If you don’t raise the sales price, your division has to increase sales volume by 14 per cent (as calculated earlier). If you increase the sales price by just 3 per cent, the sales volume increase you need to achieve your profit goal next year is only 5 per cent. Does this make sense? Well, this is just one of many alternative strategies for next year. Perhaps you could increase sales price by 4 per cent. But, you know that most of your customers are sensitive to a sales price increase, and your competitors may not follow with their own sales price increase.

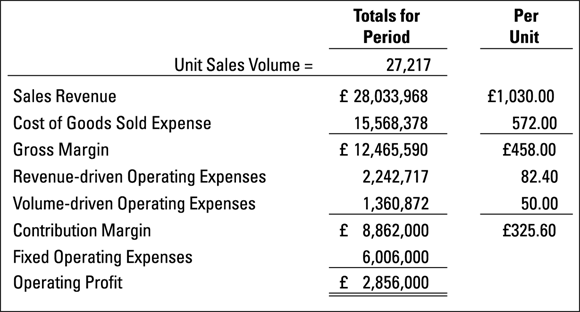

After lengthy consultation with your sales manager, you finally decide to go with the 3 per cent sales price increase combined with the 5 per cent sales volume growth as your official budget strategy. Accordingly, you forward your budgeted management Profit and Loss statement to the CEO. Figure 5-2 summarises this profit budget for the coming year. This summary-level budgeted management Profit and Loss statement is supplemented with appropriate schedules to provide additional detail about sales by types of customers and other relevant information. Also, your annual profit plan is broken down into quarters (perhaps months) to provide benchmarks for comparing actual performance during the year against your budgeted targets and timetable.

Figure 5-2: Budgeted Profit and Loss statement for coming year.

Budgeting cash flow from profit for the coming year

The budgeted profit plan (refer to Figure 5-2) is the main focus of attention, but the CEO also requests that all divisions present a budgeted cash flow from profit for the coming year. Remember: The profit you’re responsible for as general manager of the division is earnings before interest and tax (EBIT) - not net income after interest and tax.

Book IV, Chapter 3 explains that increases in debtors, stock and prepaid expenses hurt cash flow from profit and that increases in creditors and accrued liabilities help cash flow from profit. You should compare your budgeted management Profit and Loss statement for the coming year (Figure 5-2) with your actual statement for last year (Figure 5-1). This side-by-side comparison (not shown here) reveals that sales revenue and all expenses are higher next year.

Therefore, your short-term operating assets, as well as the liabilities that are driven by operating expenses, will increase at the higher sales revenue and expense levels next year - unless you can implement changes to prevent the increases.

For example, sales revenue increases from £26,000,000 last year to the budgeted £28,033,968 for next year - an increase of £2,033,968. Your debtors balance was five weeks of annual sales last year. Do you plan to tighten up the credit terms offered to customers next year - a year in which you’ll raise the sales price and also plan to increase sales volume? We doubt it. More likely, you’ll keep your debtors balance at five weeks of annual sales. Assume that you decide to offer your customers the same credit terms next year. Thus, the increase in sales revenue will cause debtors to increase by £195,574 ( × £2,033,968 sales revenue increase).

For example, sales revenue increases from £26,000,000 last year to the budgeted £28,033,968 for next year - an increase of £2,033,968. Your debtors balance was five weeks of annual sales last year. Do you plan to tighten up the credit terms offered to customers next year - a year in which you’ll raise the sales price and also plan to increase sales volume? We doubt it. More likely, you’ll keep your debtors balance at five weeks of annual sales. Assume that you decide to offer your customers the same credit terms next year. Thus, the increase in sales revenue will cause debtors to increase by £195,574 ( × £2,033,968 sales revenue increase).

Last year, stock was 13 weeks of annual cost of goods sold expense. You may be in the process of implementing stock reduction techniques. If you really expect to reduce the average time stock will be held in stock before being sold, you should inform your accounting staff so that they can include this key change in the Balance Sheet and cash flow models. Otherwise, they’ll assume that the past ratios for these vital connections will continue next year.

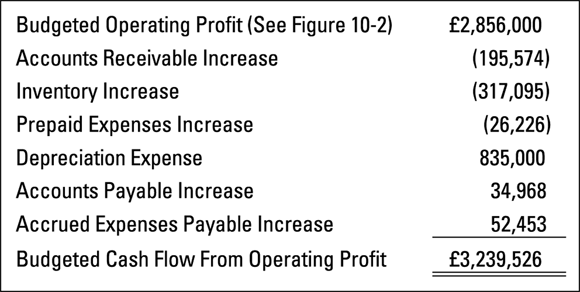

Figure 5-3 presents a summary of your budgeted cash flow from profit (the EBIT for your division) based on the information given for this example and using the ratios explained in Book IV, Chapter 3 for short-term operating assets and liabilities. For example, debtors increases by £195,574, as just explained. And stock increases by £317,095 ( × £1,268,378 cost of goods sold expense increase). Note: Increases in accrued interest payable and income tax payable aren’t included in your budgeted cash flow. Your profit responsibility ends at the operating profit line, or earnings before interest and income tax expenses.

Figure 5-3: Budgeted cash flow from profit statement for coming year.

You submit this budgeted cash flow from profit statement (Figure 5-3) to top management. Top management expects you to control the increases in your short-term assets and liabilities so that the actual cash flow generated by your division next year comes in on target. The cash flow from profit of your division (minus the small amount needed to increase the working cash balance held by your division for operating purposes) will be transferred to the central treasury of the business.

Business budgeting versus government budgeting: Only the name is the same

Business and government budgeting are more different than alike. Government budgeting is preoccupied with allocating scarce resources among many competing demands. From national agencies down to local education authorities, government entities have only so much revenue available. They have to make very difficult choices regarding how to spend their limited tax revenue.

Formal budgeting is legally required for almost all government entities. First, a budget request is submitted. After money is appropriated, the budget document becomes legally binding on the government agency. Government budgets are legal straitjackets; the government entity has to stay within the amounts appropriated for each expenditure category. Any changes from the established budgets need formal approval and are difficult to get through the system.

A business isn’t legally required to use budgeting. A business can use its budget as it pleases and can even abandon its budget in midstream. Unlike the government, the revenue of a business isn’t constrained; a business can do many things to increase sales revenue. In short, a business has much more flexibility in its budgeting. Both business and government should apply the general principle of cost/benefits analysis to make sure that they’re getting the best value for money. But a business can pass its costs to its customers in the sales prices it charges. In contrast, government has to raise taxes to spend more.

Capital Budgeting

This chapter focuses on profit budgeting for the coming year, and budgeting the cash flow from that profit. These two are hardcore components of business budgeting - but not the whole story. Another key element of the budgeting process is to prepare a capital expenditures budget for top management review and approval. A business has to take a hard look at its long-term operating assets - in particular, the capacity, condition and efficiency of these resources - and decide whether it needs to expand and modernise its fixed assets. In most cases, a business would have to invest substantial sums of money in purchasing new fixed assets or retrofitting and upgrading its old fixed assets. These long-term investments require major cash outlays. So, a business (or each division of the business) prepares a formal list of the fixed assets to be purchased or upgraded. The money for these major outlays comes from the central treasury of the business. Accordingly, the capital expenditures budget goes to the highest levels in the organisation for review and final approval. The chief financial officer, the CEO and the board of directors of the business go over a capital expenditure budget request with a fine-tooth comb.

At the company-wide level, the financial officers merge the profit and cash flow budgets of all divisions. The budgets submitted by one or more of the divisions may be returned for revision before final approval is given. One main concern is whether the collective total of cash flow from all the units provides enough money for the capital expenditures that have to be made during the coming year for new fixed assets - and to meet the other demands for cash, such as for cash distributions from profit. The business may have to raise more capital from debt or equity sources during the coming year to close the gap between cash flow from profit and its needs for cash. The financial officers need to be sure that any proposed capital expenditures make good business sense. We look at this in the next three sections. If the expenditure is worthwhile, they may need to raise more money to pay for it.

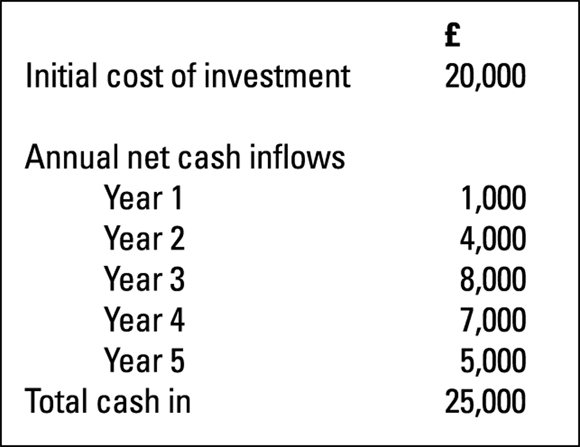

Deducing payback

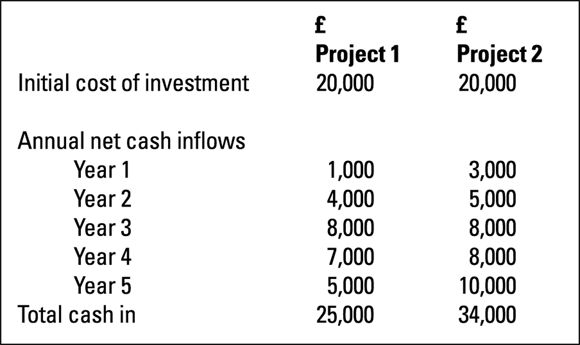

The simplest way to evaluate an investment is to calculate payback - how long it takes you to get your money back. Figure 5-4 shows an investment that calls for £20,000 cash up front in the expectation of getting £25,000 cash back over the next five years. The investment is forecasted to return a total of £20,000 by the end of year 4, so we say that this investment has a four-year payback.

Figure 5-4: Calculating payback.

When calculating the return on long-term investments, we use cash rather than profit. This is because we need to compare like with like: investments are paid for in cash or by committing cash, so we need to calculate the return using cash too.

When calculating the return on long-term investments, we use cash rather than profit. This is because we need to compare like with like: investments are paid for in cash or by committing cash, so we need to calculate the return using cash too.

Let’s suppose that we have two competing projects from which we have to choose only one. Figure 5-5 sets out the maths. Both projects have a four-year payback, in that the outlay is recovered in that period; so this technique tells us that both projects are equally acceptable, as long as we’re content to recover our outlay by year 4.

Figure 5-5: Comparing investments using payback.

However, this is only part of the story. We can see at a glance that Project 2 produces £9,000 more cash over five years than Project 1 does. We also get a lot more cash back in the first two years with Project 2, which must be better - as well as safer for the investor. Payback fails to send those signals, but is still a popular tool because of its simplicity.

Discounting cash flow

A pound today is more valuable than a pound in one, two or more years’ time. For us to make sound investment decisions, we need to ask how much we would pay now to get a pound back at some date in the future. If we know we can earn 10 per cent interest from a bank then we would only pay out 90p now to get that pound in one year’s time. The 90p represents the net present value (NPV) of that pound - the amount we would pay now to get the cash at some future date.

In effect what we’re doing is discounting the future cash flow using a percentage that equates to the minimum return that we want to earn. The further out that return, the less we would pay now in order to get it.

The formula we use to discount the cash flow is

The formula we use to discount the cash flow is

· Present value (PV) = £P × 1/(1+r) n

where £P is the initial investment, r is the interest expressed as a decimal and n is the year when the cash will flow in. (For example, in year 1 n =1, in year 2 it will be 2 and so on). So if we require a 15 per cent return, we should only be prepared to pay 87p now to get £1 in one year’s time, 76p for a pound in two years’ time and just 50p now for a pound coming in five years’ time.

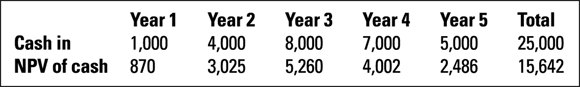

Take a look at Figure 5-6. If we use a discount rate of 15 per cent (which is a very average return on capital for a business), the picture doesn’t look so rosy. Far from paying back in four years and producing £25,000 cash for an outlay of £20,000, Project 1 is actually paying out less money (£15,642) in real terms, allowing for the time value of money, than we’ave paid out.

Figure 5-6: Comparing cash with the net present value of that cash at 15 per cent discount rate.

Calculating the internal rate of return

NPV is a powerful concept, though a slightly esoteric one. All we know so far about our attempt to evaluate Project 1 is that if we aim for a return of 15 per cent, our returns will be disappointing. So, we move on to the next stage in our quest for a sound way to appraise capital investment proposals - calculating exactly what the return on investment will be.

To arrive at this figure we need to calculate the actual return the project made on the discounted cash flow - the internal rate of return (IRR). To do this, we need to find the value for ‘r’ in the NPV formula (see the section ‘Discounting cash flow’) that ensures the present value of the future cash flow equals the cost of the investment. In the case of Project 1, the IRR is just short of 7 per cent.

The IRR is a number you can use to compare one project with another to assess quickly which is superior from a financial point of view. For example, Project 2 has an IRR of 17 per cent, which is clearly better than that of Project 1, a fact not revealed by using the payback method.

Arriving at the cost of capital

No new capital investment would make much sense if it didn’t at least cover the cost of the capital used to finance it. This cost is known in the trade as the hurdle rate, because that is the level of return any project has to beat. Say you’ve worked out the cost of equity as being 15 per cent. That should cover the dividends and the fairly high costs associated with raising the dosh. Next comes the cost of borrowed capital (and that of any other long-term source of finance such as hire purchase or mortgages). That figure is usually fairly self-evident because the lender will state this up front; however, you may have to make a judgement call here if your loans have a variable rate of interest; that is, one that can go up and down with the general bank rate. Then you have to make an educated guess as to what that might be over the life of the loan.

Next you need to combine the cost of equity and debt capital into one overall cost of capital figure; in essence, your hurdle rate.

An average cost is required because you don’t usually identify each individual project with one particular source of finance. Generally, businesses take the view that all projects have been financed from a common pool of money except for the relatively rare case when project specific finance is raised.

Assume your company intends to keep the gearing ratio of borrowed capital to equity in the proportion of 20:80. (Push ahead to Book VI, Chapter 2 if gearing isn’t a term in your Scrabble vocabulary.) The cost of new capital from these sources has been assessed, say, at 10 per cent and 15 per cent respectively, and corporation tax is 30 per cent. The calculation of the overall weighted average cost is as follows:

Assume your company intends to keep the gearing ratio of borrowed capital to equity in the proportion of 20:80. (Push ahead to Book VI, Chapter 2 if gearing isn’t a term in your Scrabble vocabulary.) The cost of new capital from these sources has been assessed, say, at 10 per cent and 15 per cent respectively, and corporation tax is 30 per cent. The calculation of the overall weighted average cost is as follows:

|

Type of capital |

Proportion (a) |

After-tax cost (b) |

Weighted cost (a x b) |

|

10% loan capital |

0.20 |

7.0% |

1.4% |

|

Equity |

0.80 |

15.0% |

12.0% |

|

13.4% |

The resulting weighted average cost of 13.4 per cent is the minimum rate that this company should accept on proposed investments. Any investment that isn’t expected to achieve this return isn’t a viable proposition.

Reporting on Variances

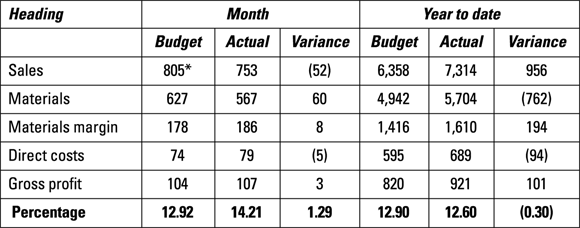

Any performance needs to be carefully monitored and compared against the budget as the year proceeds, and corrective action must be taken where necessary to keep the two consistent. This has to be done on a monthly basis (or using shorter time intervals if required), showing both the company’s performance during the month in question and throughout the year so far.

Looking at Figure 5-7, you can see at a glance that the business is behind on sales for this month, but ahead on the yearly target. The convention is to put all unfavourable variations in brackets. Hence, a higher-than-budgeted sales figure doesn’t have brackets, but a higher materials cost does. You can also see that profit is running ahead of budget but the profit margin is slightly behind (-0.30 per cent). This is partly because other direct costs, such as labour and distribution in this example, are running well ahead of budgeting variances.

Figure 5-7: Fixed budget - note that figures rounded up and down to nearest thousand may affect percentages.

Flexing your budget

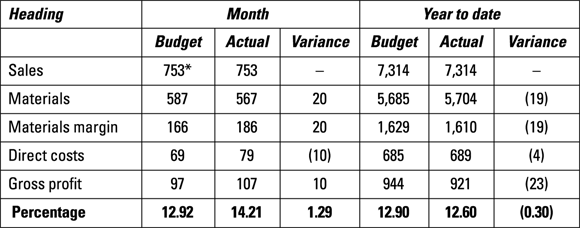

A budget is based on a particular set of sales goals, few of which are likely to be met exactly in practice. Figure 5-7 shows that the business has used £762,000 more materials than budgeted. Because more has been sold, this is hardly surprising. The way to manage this situation is to flex the budget to show what would be expected to happen to expenses, given the sales that actually occurred. This is done by applying the budget ratios to the actual data. For example, materials were planned to be 22.11 per cent of sales in the budget. By applying that to the actual month’s sales, you arrive at a materials cost of £587,000.

Looking at the flexed budget in Figure 5-8, you can see that the business has spent £19,000 more than expected on the material given the level of sales actually achieved, rather than the £762,000 overspend shown in the fixed budget. The same principle holds for other direct costs, which appear to be running £94,000 over-budget for the year. When you take into account the extra sales shown in the flexed budget, you can see that the company has actually spent £4,000 over-budget on direct costs. This is serious, but it isn’t as serious as the fixed budget suggests. The flexed budget allows you to concentrate your efforts on dealing with true variances in performance.

Figure 5-8: Flexed budget - note that figures rounded up and down to nearest thousand may affect percent-ages.

Staying Flexible with Budgets

One thing never to lose sight of is that budgeting is a means to an end. It’s a tool for doing something better than you could without the tool. Preparing budgeted financial statements isn’t the ultimate objective; a budget isn’t an end in itself. The budgeting process should provide definite benefits, and businesses should use their budgeted financial statements to measure progress toward their financial objectives - and not just file them away someplace.

One thing never to lose sight of is that budgeting is a means to an end. It’s a tool for doing something better than you could without the tool. Preparing budgeted financial statements isn’t the ultimate objective; a budget isn’t an end in itself. The budgeting process should provide definite benefits, and businesses should use their budgeted financial statements to measure progress toward their financial objectives - and not just file them away someplace.

Budgets aren’t the only tool for management control. Control means accomplishing your financial objectives. Many businesses don’t use budgeting and don’t prepare budgeted financial statements. But they do lay down goals and objectives for each period and compare actual performance against these targets. Doing at least this much is essential for all businesses.

Keep in mind that budgets aren’t the only means for controlling expenses. Actually, we shy away from the term controlling because we’ve found that, in the minds of most people, controlling expenses means minimising them. The cost/benefits idea captures the better view of expenses. Spending more on advertising, for example, may have a good payoff in the additional sales volume it produces. In other words, it’s easy to cut advertising to zero if you really want to minimise this expense - but the impact on sales volume may be disastrous.

Keep in mind that budgets aren’t the only means for controlling expenses. Actually, we shy away from the term controlling because we’ve found that, in the minds of most people, controlling expenses means minimising them. The cost/benefits idea captures the better view of expenses. Spending more on advertising, for example, may have a good payoff in the additional sales volume it produces. In other words, it’s easy to cut advertising to zero if you really want to minimise this expense - but the impact on sales volume may be disastrous.

Business managers should eliminate any excessive amount of an expense - the amount that really doesn’t yield a benefit or add value to the business. For example, it’s possible for a business to spend too much on quality inspection by doing unnecessary or duplicate steps, or by spending too much time testing products that have a long history of good quality. But this doesn’t mean that the business should eliminate the expense entirely. Expense control means trimming the cost down to the right size. In this sense, expense control is one of the hardest jobs that business managers do, second only to managing people, in our opinion.

Have a Go

Use the following figures to answer the questions in this section:

|

Volume: 30,000 units |

£/Unit |

|

|

Sales revenue |

£30,000,000 |

£1,000 |

|

Cost of goods sold expense |

(£15,600,000) |

(£520) |

|

Gross margin |

£14,400,000 |

£480 |

|

Revenue-driven operating expense |

£2,400,000 |

£80 |

|

Volume-driven operating expense |

£1,500,000 |

£50 |

|

Contribution margin |

£10,500,000 |

£350 |

|

Fixed operating expenses |

(£6,250,000) |

|

|

Operating profit |

£4,250,000 |

You’re the divisional manager of a large corporation and responsible for the budget of that division. The CEO of your company wants you to increase your EBIT by 15 per cent (£637,500 to be exact). Revenue- and volume-driven expenses remain the same for this year, but you and your staff forecast that fixed overheads are likely to rise by approximately 5 per cent to £6,562,500.

Have a go at these questions:

1. Calculate the total contribution margin for your division, given the increase in fixed overheads and the increased EBIT that your CEO wants you to achieve.

2. Your new production manager tells you that costs per unit are going to increase by £20 per unit. Recalculate your contribution per unit and then calculate the additional number of units that you’d need to sell to achieve the new EBIT with the revised production costs.

3. Your sales manager tells you that his team can’t achieve the budgeted increase in sales of 15 per cent. So you decide to make a 5 per cent sales price increase as well. Calculate the revised contribution per unit, to include the new 5 per cent sales price increase.

4. Now that you’ve calculated your revised contribution per unit (taking into account the increased sales price and increased production costs), calculate the number of the units that need to be sold to achieve the new contribution margin that your CEO requires.

5. What is the budgeted profit for the year, given the revised contribution per unit and the newly calculated sales volume of 33,092 units?

Answering the Have a Go Questions

1. The new EBIT is calculated as the existing operating profit plus the budgeted increase of £637,500:

o £4,887,500 (£4,250,000 + £637,500)

o You calculate the new contribution margin as follows:

o EBIT + budgeted fixed operating expenses (£6,250,000 + 5%)

o = £4,887,500 + £6,562,500

o = £11,450,000

2. Using the original figures given for these questions, you can see that the contribution per unit started at £350. If the production cost of each unit increases by £20, this decreases the contribution per unit to £330 (£350 - £20).

To calculate the number of units required to be sold to achieve the contribution margin of £11,450,000 (as calculated in the first question):

o Total contribution ÷ Revised contribution per unit

o £11,450,000 ÷ £330

o = 34,697 units

o An increase of 4,697 (15.5% increase) units need to be sold to achieve the new contribution margin that the CEO requires.

3. You calculate the revised contribution per unit to include the new 5 per cent sales price increase as follows:

|

Revised sales revenue £1,050 (£1,000 + 5%) |

|

Less production cost (£570) (£550 + £20 increase) |

|

Less revenue-driven expense (£84) (£80 + 5% increase) |

|

Less volume-driven expense (£50) |

|

Contribution per unit £346 |

4. You calculate the number of the units that need to be sold to achieve the new contribution margin that your CEO requires as follows:

o Total contribution margin ÷ Revised contribution per unit

o £11,450,000 ÷ £346

o = 33,092 units to sell

o This is 3,092 units more than originally sold (a 10 per cent sales volume increase).

5. The budgeted profit for the year is as follows:

|

Volume: 33,092 |

£/Unit |

|

|

Sales revenue |

£34,746,600 |

£1,050 |

|

Cost of goods sold |

(£18,862,440) |

(£570) |

|

Gross margin |

£15,884,160 |

|

|

Revenue-driven operating expense |

(£2,779,728) |

(£84) |

|

Volume-driven operating expense |

(£1,654,600) |

(£50) |

|

Contribution margin |

£11,449,832* |

|

|

Fixed operating expenses |

(£6,562,500) |

|

|

Operating profit |

£4,887,332 |

* A slight rounding exists on the contribution margin, due to the way that I rounded up the sales volume.