Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty - Daron Acemoğlu, James A. Robinson (2012)

Chapter 6. DRIFTING APART

HOW VENICE BECAME A MUSEUM

THE GROUP OF ISLANDS that form Venice lie at the far north of the Adriatic Sea. In the Middle Ages, Venice was possibly the richest place in the world, with the most advanced set of inclusive economic institutions underpinned by nascent political inclusiveness. It gained its independence in AD 810, at what turned out to be a fortuitous time. The economy of Europe was recovering from the decline it had suffered as the Roman Empire collapsed, and kings such as Charlemagne were reconstituting strong central political power. This led to stability, greater security, and an expansion of trade, which Venice was in a unique position to take advantage of. It was a nation of seafarers, placed right in the middle of the Mediterranean. From the East came spices, Byzantine-manufactured goods, and slaves. Venice became rich. By 1050, when Venice had already been expanding economically for at least a century, it had a population of 45,000 people. This increased by more than 50 percent, to 70,000, by 1200. By 1330 the population had again increased by another 50 percent, to 110,000; Venice was then as big as Paris, and probably three times the size of London.

One of the key bases for the economic expansion of Venice was a series of contractual innovations making economic institutions much more inclusive. The most famous was the commenda, a rudimentary type of joint stock company, which formed only for the duration of a single trading mission. A commenda involved two partners, a “sedentary” one who stayed in Venice and one who traveled. The sedentary partner put capital into the venture, while the traveling partner accompanied the cargo. Typically, the sedentary partner put in the lion’s share of the capital. Young entrepreneurs who did not have wealth themselves could then get into the trading business by traveling with the merchandise. It was a key channel of upward social mobility. Any losses in the voyage were shared according to the amount of capital the partners had put in. If the voyage made money, profits were based on two types of commenda contracts. If the commenda was unilateral, then the sedentary merchant provided 100 percent of the capital and received 75 percent of the profits. If it was bilateral, the sedentary merchant provided 67 percent of the capital and received 50 percent of the profits. Studying official documents, one sees how powerful a force the commenda was in fostering upward social mobility: these documents are full of new names, people who had previously not been among the Venetian elite. In government documents of AD 960, 971, and 982, the number of new names comprise 69 percent, 81 percent, and 65 percent, respectively, of those recorded.

This economic inclusiveness and the rise of new families through trade forced the political system to become even more open. The doge, who governed Venice, was selected for life by the General Assembly. Though a general gathering of all citizens, in practice the General Assembly was dominated by a core group of powerful families. Though the doge was very powerful, his power was gradually reduced over time by changes in political institutions. After 1032 the doge was elected along with a newly created Ducal Council, whose job was also to ensure that the doge did not acquire absolute power. The first doge hemmed in by this council, Domenico Flabianico, was a wealthy silk merchant from a family that had not previously held high office. This institutional change was followed by a huge expansion of Venetian mercantile and naval power. In 1082 Venice was granted extensive trade privileges in Constantinople, and a Venetian Quarter was created in that city. It soon housed ten thousand Venetians. Here we see inclusive economic and political institutions beginning to work in tandem.

The economic expansion of Venice, which created more pressure for political change, exploded after the changes in political and economic institutions that followed the murder of the doge in 1171. The first important innovation was the creation of a Great Council, which was to be the ultimate source of political power in Venice from this point on. The council was made up of officeholders of the Venetian state, such as judges, and was dominated by aristocrats. In addition to these officeholders, each year a hundred new members were nominated to the council by a nominating committee whose four members were chosen by lot from the existing council. The council also subsequently chose the members for two subcouncils, the Senate and the Council of Forty, which had various legislative and executive tasks. The Great Council also chose the Ducal Council, which was expanded from two to six members. The second innovation was the creation of yet another council, chosen by the Great Council by lot, to nominate the doge. Though the choice had to be ratified by the General Assembly, since they nominated only one person, this effectively gave the choice of doge to the council. The third innovation was that a new doge had to swear an oath of office that circumscribed ducal power. Over time these constraints were continually expanded so that subsequent doges had to obey magistrates, then have all their decisions approved by the Ducal Council. The Ducal Council also took on the role of ensuring that the doge obeyed all decisions of the Great Council.

These political reforms led to a further series of institutional innovations: in law, the creation of independent magistrates, courts, a court of appeals, and new private contract and bankruptcy laws. These new Venetian economic institutions allowed the creation of new legal business forms and new types of contracts. There was rapid financial innovation, and we see the beginnings of modern banking around this time in Venice. The dynamic moving Venice toward fully inclusive institutions looked unstoppable.

But there was a tension in all this. Economic growth supported by the inclusive Venetian institutions was accompanied by creative destruction. Each new wave of enterprising young men who became rich via the commenda or other similar economic institutions tended to reduce the profits and economic success of established elites. And they did not just reduce their profits; they also challenged their political power. Thus there was always a temptation, if they could get away with it, for the existing elites sitting in the Great Council to close down the system to these new people.

At the Great Council’s inception, membership was determined each year. As we saw, at the end of the year, four electors were randomly chosen to nominate a hundred members for the next year, who were automatically selected. On October 3, 1286, a proposal was made to the Great Council that the rules be amended so that nominations had to be confirmed by a majority in the Council of Forty, which was tightly controlled by elite families. This would have given this elite veto power over new nominations to the council, something they previously had not had. The proposal was defeated. On October 5, 1286, another proposal was put forth; this time it passed. From then on there was to be automatic confirmation of a person if his fathers and grandfathers had served on the council. Otherwise, confirmation was required by the Ducal Council. On October 17 another change in the rules was passed stipulating that an appointment to the Great Council must be approved by the Council of Forty, the doge, and the Ducal Council.

The debates and constitutional amendments of 1286 presaged La Serrata (“The Closure”) of Venice. In February 1297, it was decided that if you had been a member of the Great Council in the previous four years, you received automatic nomination and approval. New nominations now had to be approved by the Council of Forty, but with only twelve votes. After September 11, 1298, current members and their families no longer needed confirmation. The Great Council was now effectively sealed to outsiders, and the initial incumbents had become a hereditary aristocracy. The seal on this came in 1315, with the Libro d’Oro, or “Gold Book,” which was an official registry of the Venetian nobility.

Those outside this nascent nobility did not let their powers erode without a struggle. Political tensions mounted steadily in Venice between 1297 and 1315. The Great Council partially responded by making itself bigger. In an attempt to co-opt its most vocal opponents, it grew from 450 to 1,500. This expansion was complemented by repression. A police force was introduced for the first time in 1310, and there was a steady growth in domestic coercion, undoubtedly as a way of solidifying the new political order.

Having implemented a political Serrata, the Great Council then moved to adopt an economic Serrata. The switch toward extractive political institutions was now being followed by a move toward extractive economic institutions. Most important, they banned the use of commenda contracts, one of the great institutional innovations that had made Venice rich. This shouldn’t be a surprise: the commenda benefited new merchants, and now the established elite was trying to exclude them. This was just one step toward more extractive economic institutions. Another step came when, starting in 1314, the Venetian state began to take over and nationalize trade. It organized state galleys to engage in trade and, from 1324 on, began to charge individuals high levels of taxes if they wanted to engage in trade. Long-distance trade became the preserve of the nobility. This was the beginning of the end of Venetian prosperity. With the main lines of business monopolized by the increasingly narrow elite, the decline was under way. Venice appeared to have been on the brink of becoming the world’s first inclusive society, but it fell to a coup. Political and economic institutions became more extractive, and Venice began to experience economic decline. By 1500 the population had shrunk to one hundred thousand. Between 1650 and 1800, when the population of Europe rapidly expanded, that of Venice contracted.

Today the only economy Venice has, apart from a bit of fishing, is tourism. Instead of pioneering trade routes and economic institutions, Venetians make pizza and ice cream and blow colored glass for hordes of foreigners. The tourists come to see the pre-Serrata wonders of Venice, such as the Doge’s Palace and the lions of St. Mark’s Cathedral, which were looted from Byzantium when Venice ruled the Mediterranean. Venice went from economic powerhouse to museum.

IN THIS CHAPTER we focus on the historical development of institutions in different parts of the world and explain why they evolved in different ways. We saw in chapter 4 how the institutions of Western Europe diverged from those in Eastern Europe and then how those of England diverged from those in the rest of Western Europe. This was a consequence of small institutional differences, mostly resulting from institutional drift interacting with critical junctures. It might then be tempting to think that these institutional differences are the tip of a deep historical iceberg where under the waterline we find English and European institutions inexorably drifting away from those elsewhere, based on historical events dating back millennia. The rest, as they say, is history.

Except that it isn’t, for two reasons. First, moves toward inclusive institutions, as our account of Venice shows, can be reversed. Venice became prosperous. But its political and economic institutions were overthrown, and that prosperity went into reverse. Today Venice is rich only because people who make their income elsewhere choose to spend it there admiring the glory of its past. The fact that inclusive institutions can go into reverse shows that there is no simple cumulative process of institutional improvement.

Second, small institutional differences that play a crucial role during critical junctures are by their nature ephemeral. Because they are small, they can be reversed, then can reemerge and be reversed again. We will see in this chapter that, in contrast with what one would expect from the geography or culture theories, England, where the decisive step toward inclusive institutions would take place in the seventeenth century, was a backwater, not only in the millennia following the Neolithic Revolution in the Middle East but also at the beginning of the Middle Ages, following the fall of the Western Roman Empire. The British Isles were marginal to the Roman Empire, certainly of less importance than continental Western Europe, North Africa, the Balkans, Constantinople, or the Middle East. When the Western Roman Empire collapsed in the fifth century AD, Britain suffered the most complete decline. But the political revolutions that would ultimately bring the Industrial Revolution would take place not in Italy, Turkey, or even western continental Europe, but in the British Isles.

In understanding the path to England’s Industrial Revolution and the countries that followed it, Rome’s legacy is nonetheless important for several reasons. First, Rome, like Venice, underwent major early institutional innovations. As in Venice, Rome’s initial economic success was based on inclusive institutions—at least by the standards of their time. As in Venice, these institutions became decidedly more extractive over time. With Rome, this was a consequence of the change from the Republic (510 BC-49 BC) to the Empire (49 BC-AD 476). Even though during the Republican period Rome built an impressive empire, and long-distance trade and transport flourished, much of the Roman economy was based on extraction. The transition from republic to empire increased extraction and ultimately led to the kind of infighting, instability, and collapse that we saw with the Maya city-states.

Second and more important, we will see that Western Europe’s subsequent institutional development, though it was not a direct inheritance of Rome, was a consequence of critical junctures that were common across the region in the wake of the collapse of the Western Roman Empire. These critical junctures had little parallel in other parts of the world, such as Africa, Asia, or the Americas, though we will also show via the history of Ethiopia that when other places did experience similar critical junctures, they sometimes reacted in ways that were remarkably similar. Roman decline led to feudalism, which, as a by-product, caused slavery to wither away, brought into existence cities that were outside the sphere of influence of monarchs and aristocrats, and in the process created a set of institutions where the political powers of rulers were weakened. It was upon this feudal foundation that the Black Death would create havoc and further strengthen independent cities and peasants at the expense of monarchs, aristocrats, and large landowners. And it was on this canvas that the opportunities created by the Atlantic trade would play out. Many parts of the world did not undergo these changes, and in consequence drifted apart.

ROMAN VIRTUES …

Roman plebeian tribune Tiberius Gracchus was clubbed to death in 133 BC by Roman senators and his body was thrown unceremoniously into the Tiber. His murderers were aristocrats like Tiberius himself, and the assassination was masterminded by his cousin Publius Cornelius Scipio Nasica. Tiberius Gracchus had an impeccable aristocratic pedigree as a descendant of some of the more illustrious leaders of the Roman Republic, including Lucius Aemilius Paullus, hero of the Illyrian and Second Punic wars, and Scipio Africanus, the general who defeated Hannibal in the Second Punic War. Why had the powerful senators of his day, even his cousin, turned against him?

The answer tells us much about the tensions in the Roman Republic and the causes of its subsequent decline. What pitted Tiberius against these powerful senators was his willingness to stand against them in a crucial question of the day: the allocation of land and the rights of plebeians, common Roman citizens.

By the time of Tiberius Gracchus, Rome was a well-established republic. Its political institutions and the virtues of Roman citizen-soldiers—as captured by Jacques-Louis David’s famous painting Oath of the Horatii, which shows the sons swearing to their fathers that they will defend the Roman Republic to their death—are still seen by many historians as the foundation of the republic’s success. Roman citizens created the republic by overthrowing their king, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, known as Tarquin the Proud, around 510 BC. The republic cleverly designed political institutions with many inclusive elements. It was governed by magistrates elected for a year. That the office of magistrate was elected, annually, and held by multiple people at the same time reduced the ability of any one person to consolidate or exploit his power. The republic’s institutions contained a system of checks and balances that distributed power fairly widely. This was so even if not all citizens had equal representation, as voting was indirect. There was also a large number of slaves crucial for production in much of Italy, making up perhaps one-third of the population. Slaves of course had no rights, let alone political representation.

All the same, as in Venice, Roman political institutions had pluralistic elements. The plebeians had their own assembly, which could elect the plebeian tribune, who had the power to veto actions by the magistrates, call the Plebeian Assembly, and propose legislation. It was the plebeians who put Tiberius Gracchus in power in 133 BC. Their power had been forged by “secession,” a form of strike by plebeians, particularly soldiers, who would withdraw to a hill outside the city and refuse to cooperate with the magistrates until their complaints were dealt with. This threat was of course particularly important during a time of war. It was supposedly during such a secession in the fifth century BC that citizens gained the right to elect their tribune and enact laws that would govern their community. Their political and legal protection, even if limited by our current standards, created economic opportunities for citizens and some degree of inclusivity in economic institutions. As a result, trade throughout the Mediterranean flourished under the Roman Republic. Archaeological evidence suggests that while the majority of both citizens and slaves lived not much above subsistence level, many Romans, including some common citizens, achieved high incomes, with access to public services such as a city sewage system and street lighting.

Moreover, there is evidence that there was also some economic growth under the Roman Republic. We can track the economic fortunes of the Romans from shipwrecks. The empire the Romans built was in a sense a web of port cities—from Athens, Antioch, and Alexandria in the east; via Rome, Carthage, and Cadiz; all the way to London in the far west. As Roman territories expanded, so did trade and shipping, which can be traced from shipwrecks found by archaeologists on the floor of the Mediterranean. These wrecks can be dated in many ways. Often the ships carried amphorae full of wine or olive oil, being transported from Italy to Gaul, or Spanish olive oil to be sold or distributed for free in Rome. Amphorae, sealed vessels made of clay, often contained information on who had made them and when. Just near the river Tiber in Rome is a small hill, Monte Testaccio, also known as Monte dei Cocci (“Pottery Mountain”), made up of approximately fifty-three million amphorae. When the amphorae were unloaded from ships, they were discarded, over the centuries creating a huge hill.

Other goods on the ships and the ship itself can sometimes be dated using radiocarbon dating, a powerful technique used by archaeologists to date the age of organic remains. Plants create energy by photosynthesis, which uses the energy from the sun to convert carbon dioxide into sugars. As they do this, plants incorporate a quantity of a naturally occurring radioisotope, carbon-14. After plants die, the carbon-14 deteriorates due to radioactive decay. When archaeologists find a shipwreck, they can date the ship’s wood by comparing the remaining carbon-14 fraction in it to that expected from atmospheric carbon-14. This gives an estimate of when the tree was cut down. Only about 20 shipwrecks have been dated to as long ago as 500 BC. These were probably not Roman ships, and could well have been Carthaginian, for example. But then the number of Roman shipwrecks increases rapidly. Around the time of the birth of Christ, they reached a peak of 180.

Shipwrecks are a powerful way of tracing the economic contours of the Roman Republic, and they do show evidence of some economic growth, but they have to be kept in perspective. Probably two-thirds of the contents of the ships were the property of the Roman state, taxes and tribute being brought back from the provinces to Rome, or grain and olive oil from North Africa to be handed out free to the citizens of the city. It is these fruits of extraction that mostly constructed Monte Testaccio.

Another fascinating way to find evidence of economic growth is from the Greenland Ice Core Project. As snowflakes fall, they pick up small quantities of pollution in the atmosphere, particularly the metals lead, silver, and copper. The snow freezes and piles up on top of the snow that fell in previous years. This process has been going on for millennia, and provides an unrivaled opportunity for scientists to understand the extent of atmospheric pollution thousands of years ago. In 1990-1992 the Greenland Ice Core Project drilled down through 3,030 meters of ice covering about 250,000 years of human history. One of the major findings of this project, and others preceding it, was that there was a distinct increase in atmospheric pollutants starting around 500 BC. Atmospheric quantities of lead, silver, and copper then increased steadily, reaching a peak in the first century AD. Remarkably, this atmospheric quantity of lead is reached again only in the thirteenth century. These findings show how intense, compared with what came before and after, Roman mining was. This upsurge in mining clearly indicates economic expansion.

But Roman growth was unsustainable, occurring under institutions that were partially inclusive and partially extractive. Though Roman citizens had political and economic rights, slavery was widespread and very extractive, and the elite, the senatorial class, dominated both the economy and politics. Despite the presence of the Plebeian Assembly and plebeian tribute, for example, real power rested with the Senate, whose members came from the large landowners constituting the senatorial class. According to the Roman historian Livy, the Senate was created by Rome’s first king, Romulus, and consisted of one hundred men. Their descendants made up the senatorial class, though new blood was also added. The distribution of land was very unequal and most likely became more so by the second century BC. This was at the root of the problems that Tiberius Gracchus brought to the fore as tribune.

As its expansion throughout the Mediterranean continued, Rome experienced an influx of great riches. But this bounty was captured mostly by a few wealthy families of senatorial rank, and inequality between rich and poor increased. Senators owed their wealth not only to their control of the lucrative provinces but also to their very large estates throughout Italy. These estates were manned by gangs of slaves, often captured in the wars that Rome fought. But where the land for these estates came from was equally significant. Rome’s armies during the Republic consisted of citizen-soldiers who were small landowners, first in Rome and later in other parts of Italy. Traditionally they fought in the army when necessary and then returned to their plots. As Rome expanded and the campaigns got longer, this model ceased to work. Soldiers were away from their plots for years at a time, and many landholdings fell into disuse. The soldiers’ families sometimes found themselves under mountains of debt and on the brink of starvation. Many of the plots were therefore gradually abandoned, and absorbed by the estates of the senators. As the senatorial class got richer and richer, the large mass of landless citizens gathered in Rome, often after being decommissioned from the army. With no land to return to, they sought work in Rome. By the late second century BC, the situation had reached a dangerous boiling point, both because the gap between rich and poor had widened to unprecedented levels and because there were hordes of discontented citizens in Rome ready to rebel in response to these injustices and turn against the Roman aristocracy. But political power rested with the rich landowners of the senatorial class, who were the beneficiaries of the changes that had gone on over the last two centuries. Most had no intention of changing the system that had served them so well.

According to the Roman historian Plutarch, Tiberius Gracchus, when traveling through Etruria, a region in what is now central Italy, became aware of the hardship that families of citizen-soldiers were suffering. Whether because of this experience or because of other frictions with the powerful senators of his time, he would soon embark upon a daring plan to change land allocation in Italy. He stood for plebeian tribune in 133 BC, then used his office to propose land reform: a commission would investigate whether public lands were being illegally occupied and would redistribute land in excess of the legal limit of three hundred acres to landless Roman citizens. The three-hundred-acre limit was in fact part of an old law, though ignored and not implemented for centuries. Tiberius Gracchus’s proposal sent shockwaves through the senatorial class, who were able to block implementation of his reforms for a while. When Tiberius managed to use the power of the mob supporting him to remove another tribune who threatened to veto his land reform, his proposed commission was finally founded. The Senate, though, prevented implementation by starving the commission of funds.

Things came to a head when Tiberius Gracchus claimed for his land reform commission the funds left by the king of the Greek city Pergamum to the Roman people. He also attempted to stand for tribune a second time, partly because he was afraid of persecution by the Senate after he stepped down. This gave the senators the pretext to charge that Tiberius was trying to declare himself king. He and his supporters were attacked, and many were killed. Tiberius Gracchus himself was one of the first to fall, though his death would not solve the problem, and others would attempt to reform the distribution of land and other aspects of Roman economy and society. Many would meet a similar fate. Tiberius Gracchus’s brother Gaius, for example, was also murdered by landowners, after he took the mantle from his brother.

These tensions would surface again periodically during the next century—for example, leading to the “Social War” between 91 BC and 87 BC. The aggressive defender of the senatorial interests, Lucius Cornelius Sulla, not only viciously suppressed the demands for change but also severely curtailed the powers of the plebeian tribune. The same issues would also be a central factor in the support that Julius Caesar received from the people of Rome in his fight against the Senate.

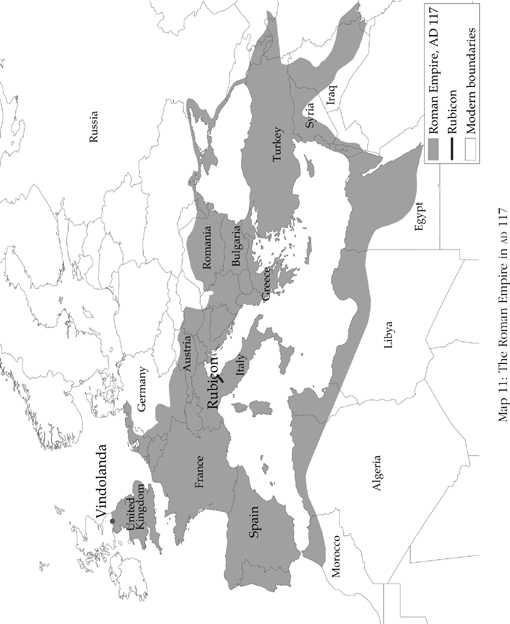

The political institutions forming the core of the Roman Republic were overthrown by Julius Caesar in 49 BC when he moved his legion across the Rubicon, the river separating the Roman provinces of Cisalpine Gaul from Italy. Rome fell to Caesar, and another civil war broke out. Though Caesar was victorious, he was murdered by disgruntled senators, led by Brutus and Cassius, in 44 BC. The Roman Republic would never be re-created. A new civil war broke out between Caesar’s supporters, particularly Mark Anthony and Octavian, and his foes. After Anthony and Octavian won, they fought each other, until Octavian emerged triumphant in the battle of Actium in 31 BC. By the following year, and for the next forty-five years, Octavian, known after 28 BC as Augustus Caesar, ruled Rome alone. Augustus created the Roman Empire, though he preferred the title princep, a sort of “first among equals,” and called the regime the Principate. Map 11 shows the Roman Empire at its greatest extent in 117 AD. It also includes the river Rubicon, which Caesar so fatefully crossed.

It was this transition from republic to principate, and later naked empire, that laid the seeds of the decline of Rome. The partially inclusive political institutions, which had formed the basis for the economic success, were gradually undermined. Even if the Roman Republic created a tilted playing field in favor of the senatorial class and other wealthy Romans, it was not an absolutist regime and had never before concentrated so much power in one position. The changes unleashed by Augustus, as with the Venetian Serrata, were at first political but then would have significant economic consequences. As a result of these changes, by the fifth century AD the Western Roman Empire, as the West was called after it split from the East, had declined economically and militarily, and was on the brink of collapse.

… ROMAN VICES

Flavius Aetius was one of the larger-than-life characters of the late Roman Empire, hailed as “the last of the Romans” by Edward Gibbon, author of The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Between AD 433 and 454, until he was murdered by the emperor Valentinian III, Aetius, a general, was probably the most powerful person in the Roman Empire. He shaped both domestic and foreign policy, and fought a series of crucial battles against the barbarians, and also other Romans in civil wars. He was unique among powerful generals fighting in civil wars in not seeking the emperorship himself. Since the end of the second century, civil war had become a fact of life in the Roman Empire. Between the death of Marcus Aurelius in AD 180 until the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in AD 476, there was hardly a decade that did not see a civil war or a palace coup against an emperor. Few emperors died of natural causes or in battle. Most were murdered by usurpers or their own troops.

Aetius’s career illustrates the changes from Roman Republic and early Empire to the late Roman Empire. Not only did his involvement in incessant civil wars and his power in every aspect of the empire’s business contrast with the much more limited power of generals and senators during earlier periods, but it also highlights how the fortunes of Romans changed radically in the intervening centuries in other ways.

By the late Roman Empire, the so-called barbarians who were initially dominated and incorporated into Roman armies or used as slaves now dominated many parts of the empire. As a young man, Aetius had been held hostage by barbarians, first by the Goths under Alaric and then by the Huns. Roman relations with these barbarians are indicative of how things had changed since the Republic. Alaric was both a ferocious enemy and an ally, so much so that in 405 he was appointed one of the senior-most generals of the Roman army. The arrangement was temporary, however. By 408, Alaric was fighting against the Romans, invading Italy and sacking Rome.

The Huns were also both powerful foes and frequent allies of the Romans. Though they, too, held Aetius hostage, they later fought alongside him in a civil war. But the Huns did not stay long on one side, and under Attila they fought a major battle against the Romans in 451, just across the Rhine. This time defending the Romans were the Goths, under Theodoric.

All of this did not stop Roman elites from trying to appease barbarian commanders, often not to protect Roman territories but to gain the upper hand in internal power struggles. For example, the Vandals, under their king, Geiseric, ravaged large parts of the Iberian Peninsula and then conquered the Roman bread baskets in North Africa from 429 onward. The Roman response to this was to offer Geiseric the emperor Valentinian III’s child daughter as a bride. Geiseric was at the time married to the daughter of one of the leaders of the Goths, but this does not seem to have stopped him. He annulled his marriage under the pretext that his wife was trying to murder him and sent her back to her family after mutilating her by cutting off both her ears and her nose. Fortunately for the bride-to-be, because of her young age she was kept in Italy and never consummated her marriage to Geiseric. Later she would marry another powerful general, Petronius Maximus, the mastermind of the murder of Aetius by the emperor Valentinian III, who would himself shortly be murdered in a plot hatched by Maximus. Maximus later declared himself emperor, but his reign would be very short, ended by his death during the major offensive by the Vandals under Geiseric against Italy, which saw Rome fall and savagely plundered.

BY THE EARLY fifth century, the barbarians were literally at the gate. Some historians argue that it was a consequence of the more formidable opponents the Romans faced during the late Empire. But the success of the Goths, Huns, and Vandals against Rome was a symptom, not the cause, of Rome’s decline. During the Republic, Rome had dealt with much more organized and threatening opponents, such as the Carthaginians. The decline of Rome had causes very similar to those of the Maya city-states. Rome’s increasingly extractive political and economic institutions generated its demise because they caused infighting and civil war.

The origins of the decline go back at least to Augustus’s seizure of power, which set in motion changes that made political institutions much more extractive. These included changes in the structure of the army, which made secession impossible, thus removing a crucial element that ensured political representation for common Romans. The emperor Tiberius, who followed Augustus in AD 14, abolished the Plebeian Assembly and transferred its powers to the Senate. Instead of a political voice, Roman citizens now had free handouts of wheat and, subsequently, olive oil, wine, and pork, and were kept entertained by circuses and gladiatorial contests. With Augustus’s reforms, emperors began to rely not so much on the army made up of citizen-soldiers, but on the Praetorian Guard, the elite group of professional soldiers created by Augustus. The Guard itself would soon become an important independent broker of who would become emperor, often through not peaceful means but civil wars and intrigue. Augustus also strengthened the aristocracy against common Roman citizens, and the growing inequality that had underpinned the conflict between Tiberius Gracchus and the aristocrats continued, perhaps even strengthened.

The accumulation of power at the center made the property rights of common Romans less secure. State lands also expanded with the empire as a consequence of confiscation, and grew to as much as half of the land in many parts of the empire. Property rights became particularly unstable because of the concentration of power in the hands of the emperor and his entourage. In a pattern not too different from what happened in the Maya city-states, infighting to take control of this powerful position increased. Civil wars became a regular occurrence, even before the chaotic fifth century, when the barbarians ruled supreme. For example, Septimius Severus seized power from Didius Julianus, who had made himself emperor after the murder of Pertinax in AD 193. Severus, the third emperor in the so-called Year of the Five Emperors, then waged war against his rival claimants, the generals Pescennius Niger and Clodius Albinus, who were finally defeated in AD 194 and 197, respectively. Severus confiscated all the property of his losing opponents in the ensuing civil war. Though able rulers, such as Trajan (AD 98 to 117), Hadrian, and Marcus Aurelius in the next century, could stanch decline, they could not, or did not want to, address the fundamental institutional problems. None of these men proposed abandoning the empire or re-creating effective political institutions along the lines of the Roman Republic. Marcus Aurelius, for all his successes, was followed by his son Commodus, who was more like Caligula or Nero than his father.

The rising instability was evident from the layout and location of towns and cities in the empire. By the third century AD every sizeable city in the empire had a defensive wall. In many cases monuments were plundered for stone, which was used in fortifications. In Gaul before the Romans had arrived in 125 BC, it was usual to build settlements on hilltops, since these were more easily defended. With the initial arrival of Rome, settlements moved down to the plains. In the third century, this trend was reversed.

Along with mounting political instability came changes in society that moved economic institutions toward greater extraction. Though citizenship was expanded to the extent that by AD 212 nearly all the inhabitants of the empire were citizens, this change went along with changes in status between citizens. Any sense that there might have been of equality before the law deteriorated. For example, by the reign of Hadrian (AD 117 to 138), there were clear differences in the types of laws applied to different categories of Roman citizen. Just as important, the role of citizens was completely different from how it had been in the days of the Roman Republic, when they were able to exercise some power over political and economic decisions through the assemblies in Rome.

Slavery remained a constant throughout Rome, though there is some controversy over whether the fraction of slaves in the population actually declined over the centuries. Equally important, as the empire developed, more and more agricultural workers were reduced to semi-servile status and tied to the land. The status of these servile “coloni” is extensively discussed in legal documents such as the Codex Theodosianus and Codex Justinianus, and probably originated during the reign of Diocletian (AD 284 to 305). The rights of landlords over the coloni were progressively increased. The emperor Constantine in 332 allowed landlords to chain a colonus whom they suspected was trying to escape, and from AD 365, coloni were not allowed to sell their own property without their landlord’s permission.

Just as we can use shipwrecks and the Greenland ice cores to track the economic expansion of Rome during earlier periods, we can use them also to trace its decline. By AD 500 the peak of 180 ships was reduced to 20. As Rome declined, Mediterranean trade collapsed, and some scholars have even argued that it did not return to its Roman height until the nineteenth century. The Greenland ice tells a similar story. The Romans used silver for coins, and lead had many uses, including for pipes and tableware. After peaking in the first century AD, the deposits of lead, silver, and copper in the ice cores declined.

The experience of economic growth during the Roman Republic was impressive, as were other examples of growth under extractive institutions, such as the Soviet Union. But that growth was limited and was not sustained, even when it is taken into account that it occurred under partially inclusive institutions. Growth was based on relatively high agricultural productivity, significant tribute from the provinces, and long-distance trade, but it was not underpinned by technological progress or creative destruction. The Romans inherited some basic technologies, iron tools and weapons, literacy, plow agriculture, and building techniques. Early on in the Republic, they created others: cement masonry, pumps, and the water wheel. But thereafter, technology was stagnant throughout the period of the Roman Empire. In shipping, for instance, there was little change in ship design or rigging, and the Romans never developed the stern rudder, instead steering ships with oars. Water wheels spread very slowly, so that water power never revolutionized the Roman economy. Even such great achievements as aqueducts and city sewers used existing technology, though the Romans perfected it. There could be some economic growth without innovation, relying on existing technology, but it was growth without creative destruction. And it did not last. As property rights became more insecure and the economic rights of citizens followed the decline of their political rights, economic growth likewise declined.

A remarkable thing about new technologies in the Roman period is that their creation and spread seem to have been driven by the state. This is good news, until the government decides that it is not interested in technological development—an all-too-common occurrence due to the fear of creative destruction. The great Roman writer Pliny the Elder relates the following story. During the reign of the emperor Tiberius, a man invented unbreakable glass and went to the emperor anticipating that he would get a great reward. He demonstrated his invention, and Tiberius asked him if he had told anyone else about it. When the man replied no, Tiberius had the man dragged away and killed, “lest gold be reduced to the value of mud.” There are two interesting things about this story. First, the man went to Tiberius in the first place for a reward, rather than setting himself up in business and making a profit by selling the glass. This shows the role of the Roman government in controlling technology. Second, Tiberius was happy to destroy the innovation because of the adverse economic effects it would have had. This is the fear of the economic effects of creative destruction.

There is also direct evidence from the period of the Empire of the fear of the political consequences of creative destruction. Suetonius tells how the emperor Vespasian, who ruled between AD 69 and 79, was approached by a man who had invented a device for transporting columns to the Capitol, the citadel of Rome, at a relatively small cost. Columns were large, heavy, and very difficult to transport. Moving them to Rome from the mines where they were made involved the labor of thousands of people, at great expense to the government. Vespasian did not kill the man, but he also refused to use the innovation, declaring, “How will it be possible for me to feed the populace?” Again an inventor came to the government. Perhaps this was more natural than with the unbreakable glass, as the Roman government was most heavily involved with column mining and transportation. Again the innovation was turned down because of the threat of creative destruction, not so much because of its economic impact, but because of fear of political creative destruction. Vespasian was concerned that unless he kept the people happy and under control it would be politically destabilizing. The Roman plebeians had to be kept busy and pliant, so it was good to have jobs to give them, such as moving columns about. This complemented the bread and circuses, which were also dispensed for free to keep the population content. It is perhaps telling that both of these examples came soon after the collapse of the Republic. The Roman emperors had far more power to block change than the Roman rulers during the Republic.

Another important reason for the lack of technological innovation was the prevalence of slavery. As the territories Romans controlled expanded, vast numbers were enslaved, often being brought back to Italy to work on large estates. Many citizens in Rome did not need to work: they lived off the handouts from the government. Where was innovation to come from? We have argued that innovation comes from new people with new ideas, developing new solutions to old problems. In Rome the people doing the producing were slaves and, later, semi-servile coloni with few incentives to innovate, since it was their masters, not they, who stood to benefit from any innovation. As we will see many times in this book, economies based on the repression of labor and systems such as slavery and serfdom are notoriously noninnovative. This is true from the ancient world to the modern era. In the United States, for example, the northern states took part in the Industrial Revolution, not the South. Of course slavery and serfdom created huge wealth for those who owned the slaves and controlled the serfs, but it did not create technological innovation or prosperity for society.

NO ONE WRITES FROM VINDOLANDA

By AD 43 the Roman emperor Claudius had conquered England, but not Scotland. A last, futile attempt was made by the Roman governor Agricola, who gave up and, in AD 85, built a series of forts to protect England’s northern border. One of the biggest of these was at Vindolanda, thirty-five miles west of Newcastle and depicted on Map 11 at the far northwest of the Roman Empire. Later, Vindolanda was incorporated into the eighty-five-mile defensive wall that the emperor Hadrian constructed, but in AD 103, when a Roman centurion, Candidus, was stationed there, it was an isolated fort. Candidus was engaged with his friend Octavius in supplying the Roman garrison and received a reply from Octavius to a letter he had sent:

Octavius to his brother Candidus, greetings.

I have several times written to you that I have bought about five thousand modii of ears of grain, on account of which I need cash. Unless you send me some cash, at least five hundred denarii, the result will be that I shall lose what I have laid out as a deposit, about three hundred denarii, and I shall be embarrassed. So, I ask you, send me some cash as soon as possible. The hides which you write are at Cataractonium—write that they be given to me and the wagon about which you write. I would have already been to collect them except that I did not care to injure the animals while the roads are bad. See with Tertius about the 8½ denarii which he received from Fatalis. He has not credited them to my account. Make sure that you send me cash so that I may have ears of grain on the threshing-floor. Greet Spectatus and Firmus. Farewell.

The correspondence between Candidus and Octavius illustrates some significant facets of the economic prosperity of Roman England: It reveals an advanced monetary economy with financial services. It reveals the presence of constructed roads, even if sometimes in bad condition. It reveals the presence of a fiscal system that raised taxes to pay Candidus’s wages. Most obviously it reveals that both men were literate and were able to take advantage of a postal service of sorts. Roman England also benefited from the mass manufacture of high-quality pottery, particularly in Oxfordshire; urban centers with baths and public buildings; and house construction techniques using mortar and tiles for roofs.

By the fourth century, all were in decline, and after AD 411 the Roman Empire gave up on England. Troops were withdrawn; those left were not paid, and as the Roman state crumbled, administrators were expelled by the local population. By AD 450 all these trappings of economic prosperity were gone. Money vanished from circulation. Urban areas were abandoned, and buildings stripped of stone. The roads were overgrown with weeds. The only type of pottery fabricated was crude and handmade, not manufactured. People forgot how to use mortar, and literacy declined substantially. Roofs were made of branches, not tiles. Nobody wrote from Vindolanda anymore.

After AD 411, England experienced an economic collapse and became a poor backwater—and not for the first time. In the previous chapter we saw how the Neolithic Revolution started in the Middle East around 9500 BC. While the inhabitants of Jericho and Abu Hureyra were living in small towns and farming, the inhabitants of England were still hunting and gathering, and would do so for at least another 5,500 years. Even then the English didn’t invent farming or herding; these were brought from the outside by migrants who had been spreading across Europe from the Middle East for thousands of years. As the inhabitants of England caught up with these major innovations, those in the Middle East were inventing cities, writing, and pottery. By 3500 BC, large cities such as Uruk and Ur emerged in Mesopotamia, modern Iraq. Uruk may have had a population of fourteen thousand in 3500 BC, and forty thousand soon afterward. The potter’s wheel was invented in Mesopotamia at about the same time as was wheeled transportation. The Egyptian capital of Memphis emerged as a large city soon thereafter. Writing appeared independently in both regions. While the Egyptians were building the great pyramids of Giza around 2500 BC, the English constructed their most famous ancient monument, the stone circle at Stonehenge. Not bad by English standards, but not even large enough to have housed one of the ceremonial boats buried at the foot of King Khufu’s pyramid. England continued to lag behind and to borrow from the Middle East and the rest of Europe up to and including the Roman period.

Despite such an inauspicious history, it was in England that the first truly inclusive society emerged and where the Industrial Revolution got under way. We argued earlier (this page-this page) that this was the result of a series of interactions between small institutional differences and critical junctures—for example, the Black Death and the discovery of the Americas. English divergence had historical roots, but the view from Vindolanda suggests that these roots were not that deep and certainly not historically predetermined. They were not planted in the Neolithic Revolution, or even during the centuries of Roman hegemony. By AD 450, at the start of what historians used to call the Dark Ages, England had slipped back into poverty and political chaos. There would be no effective centralized state in England for hundreds of years.

DIVERGING PATHS

The rise of inclusive institutions and the subsequent industrial growth in England did not follow as a direct legacy of Roman (or earlier) institutions. This does not mean that nothing significant happened with the fall of the Western Roman Empire, a major event affecting most of Europe. Since different parts of Europe shared the same critical junctures, their institutions would drift in a similar fashion, perhaps in a distinctively European way. The fall of the Roman Empire was a crucial part of these common critical junctures. This European path contrasts with paths in other parts of the world, including sub-Saharan Africa, Asia, and the Americas, which developed differently partly because they did not face the same critical junctures.

Roman England collapsed with a bang. This was less true in Italy, or Roman Gaul (modern France), or even North Africa, where many of the old institutions lived on in some form. Yet there is no doubt that the change from the dominance of a single Roman state to a plethora of states run by Franks, Visigoths, Ostrogoths, Vandals, and Burgundians was significant. The power of these states was far weaker, and they were buffeted by a long series of incursions from their peripheries. From the north came the Vikings and Danes in their longboats. From the east came the Hunnic horsemen. Finally, the emergence of Islam as a religion and political force in the century after the death of Mohammed in AD 632 led to the creation of new Islamic states in most of the Byzantine Empire, North Africa, and Spain. These common processes rocked Europe, and in their wake a particular type of society, commonly referred to as feudal, emerged. Feudal society was decentralized because strong central states had atrophied, even if some rulers such as Charlemagne attempted to reconstruct them.

Feudal institutions, which relied on unfree, coerced labor (the serfs), were obviously extractive, and they formed the basis for a long period of extractive and slow growth in Europe during the Middle Ages. But they also were consequential for later developments. For instance, during the reduction of the rural population to the status of serfs, slavery disappeared from Europe. At a time when it was possible for elites to reduce the entire rural population to serfdom, it did not seem necessary to have a separate class of slaves as every previous society had had. Feudalism also created a power vacuum in which independent cities specializing in production and trade could flourish. But when the balance of power changed after the Black Death, and serfdom began to crumble in Western Europe, the stage was set for a much more pluralistic society without the presence of any slaves.

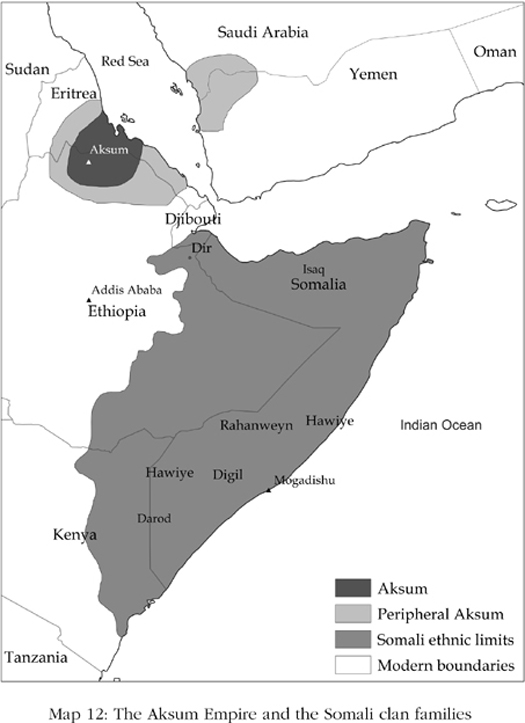

The critical junctures that gave rise to feudal society were distinct, but they were not completely restricted to Europe. A relevant comparison is with the modern African country of Ethiopia, which developed from the Kingdom of Aksum, founded in the north of the country around 400 BC. Aksum was a relatively developed kingdom for its time and engaged in international trade with India, Arabia, Greece, and the Roman Empire. It was in many ways comparable to the Eastern Roman Empire in this period. It used money, built monumental public buildings and roads, and had very similar technology, for example, in agriculture and shipping. There are also interesting ideological parallels between Aksum and Rome. In AD 312, the Roman emperor Constantine converted to Christianity, as did King Ezana of Aksum about the same time. Map 12 shows the location of the historical state of Aksum in modern-day Ethiopia and Eritrea, with outposts across the Red Sea in Saudi Arabia and Yemen.

Just as Rome declined, so did Aksum, and its historical decline followed a pattern close to that of the Western Roman Empire. The role played by the Huns and Vandals in the decline of Rome was taken by the Arabs, who, in the seventh century, expanded into the Red Sea and down the Arabian Peninsula. Aksum lost its colonies in Arabia and its trade routes. This precipitated economic decline: money stopped being coined, the urban population fell, and there was a refocusing of the state into the interior of the country and up into the highlands of modern Ethiopia.

In Europe, feudal institutions emerged following the collapse of central state authority. The same thing happened in Ethiopia, based on a system called gult, which involved a grant of land by the emperor. The institution is mentioned in thirteenth-century manuscripts, though it may have originated much earlier. The term gult is derived from an Amharic word meaning “he assigned a fief.” It signified that in exchange for the land, the gult holder had to provide services to the emperor, particularly military ones. In turn, the gult holder had the right to extract tribute from those who farmed the land. A variety of historical sources suggest that gult holders extracted between one-half and three-quarters of the agricultural output of peasants. This system was an independent development with notable similarities to European feudalism, but probably even more extractive. At the height of feudalism in England, serfs faced less onerous extraction and lost about half of their output to their lords in one form or another.

But Ethiopia was not representative of Africa. Elsewhere, slavery was not replaced by serfdom; African slavery and the institutions that supported it were to continue for many more centuries. Even Ethiopia’s ultimate path would be very different. After the seventh century, Ethiopia remained isolated in the mountains of East Africa from the processes that subsequently influenced the institutional path of Europe, such as the emergence of independent cities, the nascent constraints on monarchs and the expansion of Atlantic trade after the discovery of the Americas. In consequence, its version of absolutist institutions remained largely unchallenged. The African continent would later interact in a very different capacity with Europe and Asia. East Africa became a major supplier of slaves to the Arab world, and West and Central Africa would be drawn into the world economy during the European expansion associated with the Atlantic trade as suppliers of slaves. How the Atlantic trade led to sharply divergent paths between Western Europe and Africa is yet another example of institutional divergence resulting from the interaction between critical junctures and existing institutional differences. While in England the profits of the slave trade helped to enrich those who opposed absolutism, in Africa they helped to create and strengthen absolutism.

Farther away from Europe, the processes of institutional drift were obviously even freer to go their own way. In the Americas, for example, which had been cut off from Europe around 15,000 BC by the melting of the ice that linked Alaska to Russia, there were similar institutional innovations as those of the Natufians, leading to sedentary life, hierarchy, and inequality—in short, extractive institutions. These took place first in Mexico and in Andean Peru and Bolivia, and led to the American Neolithic Revolution, with the domestication of maize. It was in these places that early forms of extractive growth took place, as we have seen in the Maya city-states. But in the same way that big breakthroughs toward inclusive institutions and industrial growth in Europe did not come in places where the Roman world had the strongest hold, inclusive institutions in the Americas did not develop in the lands of these early civilizations. In fact, as we saw in chapter 1, these densely settled civilizations interacted in a perverse way with European colonialism to create a “reversal of fortune,” making the places that were previously relatively wealthy in the Americas relatively poor. Today it is the United States and Canada, which were then far behind the complex civilizations in Mexico, Peru, and Bolivia, that are much richer than the rest of the Americas.

CONSEQUENCES OF EARLY GROWTH

The long period between the Neolithic Revolution, which started in 9500 BC, and the British Industrial Revolution of the late eighteenth century is littered with spurts of economic growth. These spurts were triggered by institutional innovations that ultimately faltered. In Ancient Rome the institutions of the Republic, which created some degree of economic vitality and allowed for the construction of a massive empire, unraveled after the coup of Julius Caesar and the construction of the empire under Augustus. It took centuries for the Roman Empire finally to vanish, and the decline was drawn out; but once the relatively inclusive republican institutions gave way to the more extractive institutions of the empire, economic regress became all but inevitable.

The Venetian dynamics were similar. The economic prosperity of Venice was forged by institutions that had important inclusive elements, but these were undermined when the existing elite closed the system to new entrants and even banned the economic institutions that had created the prosperity of the republic.

However notable the experience of Rome, it was not Rome’s inheritance that led directly to the rise of inclusive institutions in England and to the British Industrial Revolution. Historical factors shape how institutions develop, but this is not a simple, predetermined, cumulative process. Rome and Venice illustrate how early steps toward inclusivity were reversed. The economic and institutional landscape that Rome created throughout Europe and the Middle East did not inexorably lead to the more firmly rooted inclusive institutions of later centuries. In fact, these would emerge first and most strongly in England, where the Roman hold was weakest and where it disappeared most decisively, almost without a trace, during the fifth century AD. Instead, as we discussed in chapter 4, history plays a major role through institutional drift that creates institutional differences, albeit sometimes small, which then get amplified when they interact with critical junctures. It is because these differences are often small that they can be reversed easily and are not necessarily the consequence of a simple cumulative process.

Of course, Rome had long-lasting effects on Europe. Roman law and institutions influenced the laws and institutions that the kingdoms of the barbarians set up after the collapse of the Western Roman Empire. It was also Rome’s fall that created the decentralized political landscape that developed into the feudal order. The disappearance of slavery and the emergence of independent cities were long, drawn out (and, of course, historically contingent) by-products of this process. These would become particularly consequential when the Black Death shook feudal society deeply. Out of the ashes of the Black Death emerged stronger towns and cities, and a peasantry no longer tied to the land and newly free of feudal obligations. It was precisely these critical junctures unleashed by the fall of the Roman Empire that led to a strong institutional drift affecting all of Europe in a way that has no parallel in sub-Saharan Africa, Asia, or the Americas.

By the sixteenth century, Europe was institutionally very distinct from sub-Saharan Africa and the Americas. Though not much richer than the most spectacular Asian civilizations in India or China, Europe differed from these polities in some key ways. For example, it had developed representative institutions of a sort unseen there. These were to play a critical role in the development of inclusive institutions. As we will see in the next two chapters, small institutional differences would be the ones that would really matter within Europe; and these favored England, because it was there that the feudal order had made way most comprehensively for commercially minded farmers and independent urban centers where merchants and industrialists could flourish. These groups were already demanding more secure property rights, different economic institutions, and political voice from their monarchs. This whole process would come to a head in the seventeenth century.