The Movie Book (Big Ideas Simply Explained) (2016)

INTRODUCTION

As this guide nears the end of its broad sweep of movie history, the time has come to introduce Quentin Tarantino. By the early 1990s, a century of movies was available to filmmakers to pay homage to and to repurpose. Tarantino—a movie obsessive who filled his movies with endless nudges and nods to that past—was a controversial figure from the moment the world saw his debut Reservoir Dogs. But no one could question the excitement he generated.

Beyond Hollywood

From the 1990s onward, Hollywood was increasingly one part of a bigger story. The curious audience was looking far afield, and rather than the occasional box-office breakout, it was becoming the norm for movie lovers to celebrate the movies of Southeast Asia, Turkey, India, and Latin America. Cultures clashed, to glorious effect: Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon was a martial arts extravaganza steeped in the Chinese tradition of wuxia but purpose made by its Taiwanese-American director Ang Lee to be accessible to audiences across the world. From Brazil, Fernando Meirelles’s City of God applied the stylistic swagger of Martin Scorsese to a story set in the favelas of Rio.

Digital revolution

A less heralded revolution also stirred in the last days of the 20th century. Since the dawn of cinema, filmmakers had been just that: film was not just the name of the art form, it was what physically went into cameras and projectors. In 1998, the Danish family drama Festen, filmed according to the rules of the Dogme 95 manifesto, became the first high-profile movie to be shot on digital video, then mostly used in cheap home camcorders. Nothing would be the same again. In the short term, filmmakers now had cameras so small and light they could move through scenes with boundless agility. For some (among them Tarantino), the loss of film was an ongoing tragedy. For others, digital put filmmaking in the hands of people who could never have afforded to get their ideas on screen otherwise—and made the riches of movie history accessible to anyone with a memory stick.

The digital revolution not only transformed the way movies were shot, it also changed how they were seen, as noiseless digital projection replaced the time-honored whir of 35 mm.

Other barriers were also falling. The Hurt Locker was a movie that, in 2008, felt impossibly modern—the jagged energy of its special effects ideal for a story about the Iraq War. More significant, perhaps, was that its director, Kathryn Bigelow, became the first woman to win an Oscar as Best Director.

"When people ask me if I went to film school, I tell them “no, I went to films.”"

Quentin Tarantino

Computer effects

For much of the course of this guide, “special effects” were the preserve of a certain kind of movie: big-budget spectaculars, the sons (and daughters) of King Kong and animator Ray Harryhausen. By now, movies of all kinds were being made in front of computers. German director Michael Haneke’s hypnotically austere filmmaking could hardly have been further from the additive-packed summer blockbuster; yet The White Ribbon, his tale of strange goings-on among the children of a German village in 1913, used digital technology to erase stray signs of modern life.

In the blockbuster Gravity, on the other hand, nothing was what it seemed; its outer space adventure had mostly been filmed with a lone Sandra Bullock locked for months into a “cage” in front of a green screen, “space” to be added later.

Yet Georges Méliès would surely have smiled at finding we were still thrilling ourselves with trips to the stars. While it was firmly earthbound, he would have admired Boyhood too: shot for a few days every year for 12 years to map one child’s journey through life, it sounded like a gimmick. In fact, it reminded you, with enormous power, what it was to be human. What better emblem for the movies could there be?

IN CONTEXT

GENRE

Crime, thriller

DIRECTOR

Quentin Tarantino

WRITERS

Quentin Tarantino, Roger Avary (story); Quentin Tarantino (script)

STARS

John Travolta, Samuel L. Jackson, Uma Thurman, Bruce Willis

BEFORE

1955 Noir thriller Kiss Me Deadly features a glowing suitcase that’s thought to have inspired the one in Pulp Fiction.

AFTER

1997 Similarly to Pulp Fiction, Tarantino’s Jackie Brown weaves together a large cast and many plot elements.

2003 Revenge romp Kill Bill sees Tarantino elevating Uma Thurman to a blood-soaked starring role.

In the early 1990s, a movie fanatic and video-store clerk named Quentin Tarantino, originally from Knoxville, Tennessee, had a seismic impact on American movies. Although the likes of Richard Linklater and Spike Lee had brought exciting new ideas to American cinema, it had been a long time since it had felt dangerous. Tarantino relocated to Southern California, and his debut as the director of Reservoir Dogs felt very dangerous indeed—a foul-mouthed, blood-soaked crime story that was also incredibly funny. Two years later, Tarantino followed up with Pulp Fiction, which kept up the verbal zing of its predecessor but also introduced a dazzlingly inventive structure and A-list Hollywood stars.

Tarantino’s profane, freewheeling style was like an adrenaline shot to the heart—a motif that would appear in Pulp Fiction. Part of what made him such a novelty was his approach to genre. Just as Reservoir Dogs had reimagined the heist movie, so Pulp Fiction took the conventions of the B-movie—a gangland killing, a boxer taking a dive, and a hitman in search of redemption—and repurposed them in new, brilliantly knowing ways. The result has the stylistic charge of a genre movie while remaining a genuinely original and innovative movie experience.

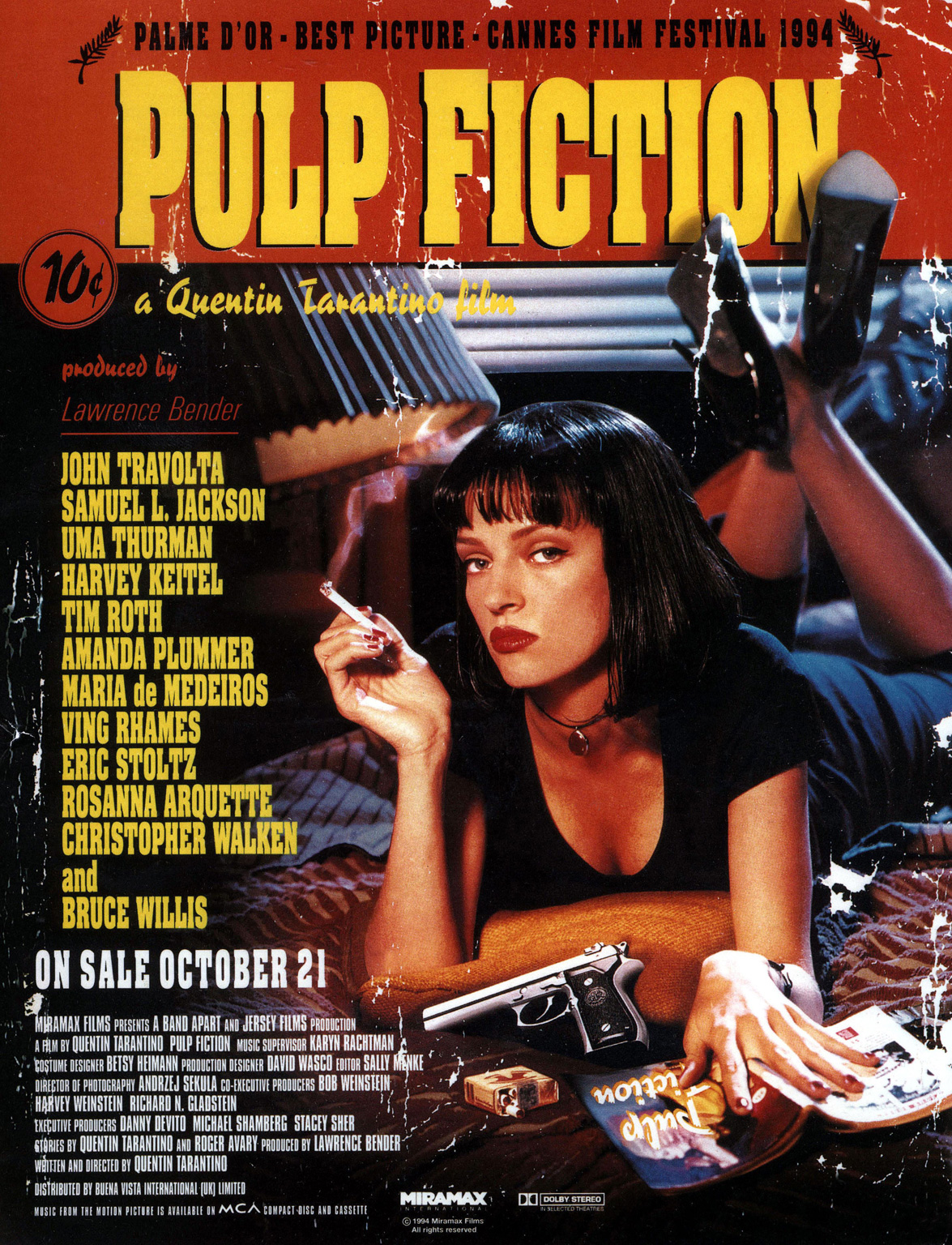

This iconic poster for Pulp Fiction apes the covers of the trashy crime novels from which it draws its title, right down to the 10-cent price tag and much-thumbed appearance.

Vincent Vega (John Travolta) pairs up with Mia Wallace (Uma Thurman) at Jack Rabbit Slim’s for some comically clichéd dance moves.

Structural shift

One of the iconic elements of Pulp Fiction is its use of nonlinear storytelling. By fracturing the narrative, Tarantino does not allow the audience to settle into the traditional rhythms of watching a crime thriller. Instead of a story with an identifiable beginning, middle, and end, the movie features a segmented structure in which three self-contained stories are told out of sync with one another. The director is careful to ensure that each segment feels like part of one world, so he connects the stories through the supporting characters: gangland kingpin Marsellus Wallace is featured prominently in the plot of all three stories, for example, and key protagonists from one story show up for walk-on parts in other plotlines. Vincent Vega (John Travolta), who spends much of the first hour as a lead character, recedes into a supporting role as the movie progresses—he shows up for a brief (and unfortunate) cameo in “The Gold Watch” storyline featuring washed-up boxer Butch Coolidge (Bruce Willis), then plays second fiddle to his partner Jules Winnfield (Samuel L. Jackson) in the final segment, as the latter experiences a spiritual awakening.

The result of this disassembled structure is that Pulp Fiction isn’t about any one character or story, but instead is almost a mood piece, designed to evoke the feel of Los Angeles and the slick but seedy characters who live there. At the end of each segment, the story’s momentum comes to a halt and the movie reboots in another place, with other people, at an indeterminate point in time.

“Nobody’s gonna hurt anybody. We’re gonna be like three little Fonzies here. And what’s Fonzie like?”

Jules / Pulp Fiction

Pulp Fiction’s nonlinear narrative starts in the middle. When its chapters are arranged chronologically, does the story seem less open-ended?

Amoral morality

Crime thrillers are not known for stories about morally upstanding individuals doing good, yet as well as having clearly identifiable heroes and villains, most of them have a distinct idea of what is right and wrong, even if that doesn’t always comply with the letter of the law. In Pulp Fiction, however, Tarantino deliberately avoids projecting his own sense of right and wrong onto his characters. The most telling instance of this is found in one of the movie’s earlier sequences, in which Vincent and Jules make their first appearance. The audience first lays eyes on them as they have a low-key conversation about fast food, during which they appear to be charismatic, likeable characters who are fun to hang out with. However, they are professional killers on their way to a hit, and following their conversation they are shown doing something monstrous, something that would traditionally be considered evil. This framing of their characters forces viewers to accept Pulp Fiction’s nonjudgmental stance and conditions them for the best way to appreciate the movie, which is simply to submit and go along for the ride.

Pulp Fiction, in all its obscene glory, is perhaps one of the best examples in movies of how originality and daring will win out. There were a lot of obstacles between the critical establishment and the movie, from its language to its violence to its subject matter (indeed, it was famously and controversially beaten to the 1995 Best Picture Oscar by Steven Spielberg’s far more conventional Forrest Gump), yet its enduring popularity shows that it functions perfectly as a showcase for Tarantino’s talent as a filmmaker, with the broken structure allowing for singular moments of directorial flair to become prominent instead of being lost as part of the whole. If you’re looking for a fresh and engrossing take on the well-trodden territory of the criminal underworld, you can’t do much better than Pulp Fiction.

Although he is being held at gunpoint, Pumpkin (Tim Roth) is about to witness a truly unusual moment of enlightenment as Jules vows to change his ways.

"You get intoxicated by it… high on the rediscovery of how pleasurable a movie can be. I’m not sure I’ve ever encountered a filmmaker who combined discipline and control with sheer wild-ass joy the way that Tarantino does."

Owen Gleiberman

Entertainment Weekly, 1994

QUENTIN TARANTINO Director

Quentin Tarantino was born in Knoxville, Tennessee, in 1963. After dropping out of high school at 15 to pursue an acting career, he was diverted into writing scripts by a meeting with producer Lawrence Bender. His first movie, Reservoir Dogs, gained him international acclaim, and his follow-up, Pulp Fiction, won the Palme d’Or as well as earning him the Oscar for Best Original Screenplay. Tarantino has since made movies in a variety of genres, from revenge thrillers in the Kill Bill series to war movies with Inglourious Basterds (2009) and Westerns with Django Unchained. His movies continue to do well with both critics and audiences.

Key movies

1992 Reservoir Dogs

1994 Pulp Fiction

2003 Kill Bill: Volume 1

2012 Django Unchained

What else to watch: Kiss Me Deadly (1955) ✵ Shoot the Piano Player (1960) ✵ Band of Outsiders (1964) ✵ Blood Simple (1984) ✵ Reservoir Dogs (1992) ✵ True Romance (1993) ✵ Jackie Brown (1997) ✵ Go (1999)