The Movie Book (Big Ideas Simply Explained) (2016)

IN CONTEXT

GENRE

Supernatural thriller

DIRECTOR

Nicolas Roeg

WRITERS

Allan Scott, Chris Bryant (screenplay); Daphne du Maurier (short story)

STARS

Donald Sutherland, Julie Christie

BEFORE

1970 Roeg’s twisted crime drama Performance stars Mick Jagger as a reclusive rock star.

AFTER

1976 David Bowie plays an alien in Roeg’s sci-fi odyssey The Man Who Fell to Earth.

1977 Julie Christie is attacked by a computer in Demon Seed, directed by Donald Cammell.

Don’t Look Now opens with the death of a child, but it’s more concerned with the fate of her parents, John (Donald Sutherland) and Laura Baxter (Julie Christie). The grieving couple relocate from their home in Britain to wintry, out-of-season Venice, where John busies himself with the restoration of a church mosaic. When Laura befriends two elderly sisters—one a blind clairvoyant—her husband begins to catch glimpses of a figure that resembles their dead daughter. Is John seeing things? Or could it be that Christine has come back from beyond the grave?

What can and cannot be “seen” is the enigma at the heart of this devastating movie, whose title seems to be a warning. “Don’t look now!” it screams, begging the audience to avert its gaze. But, as with many things in Nicolas Roeg’s paranormal chiller, the title is not what it seems. In fact Roeg wants the viewer to look carefully, especially at the patterns created by his strange, kaleidoscopic arrangement of images.

The director experimented with complex visual editing in his previous movies, Performance (1970) and Walkabout (1971); in Don’t Look Now, he uses these techniques to convey both a sense of menace and the fractured psychological states of his two main characters. Images are repeated and echoed at jarring moments: ripples on water; the color red; breaking glass; close-ups of gargoyles and statues. The viewer glimpses them here and there, just as John catches sight of the scarlet-coated figure from the corner of his eye, and they accumulate to build an atmosphere thick with paranoia.

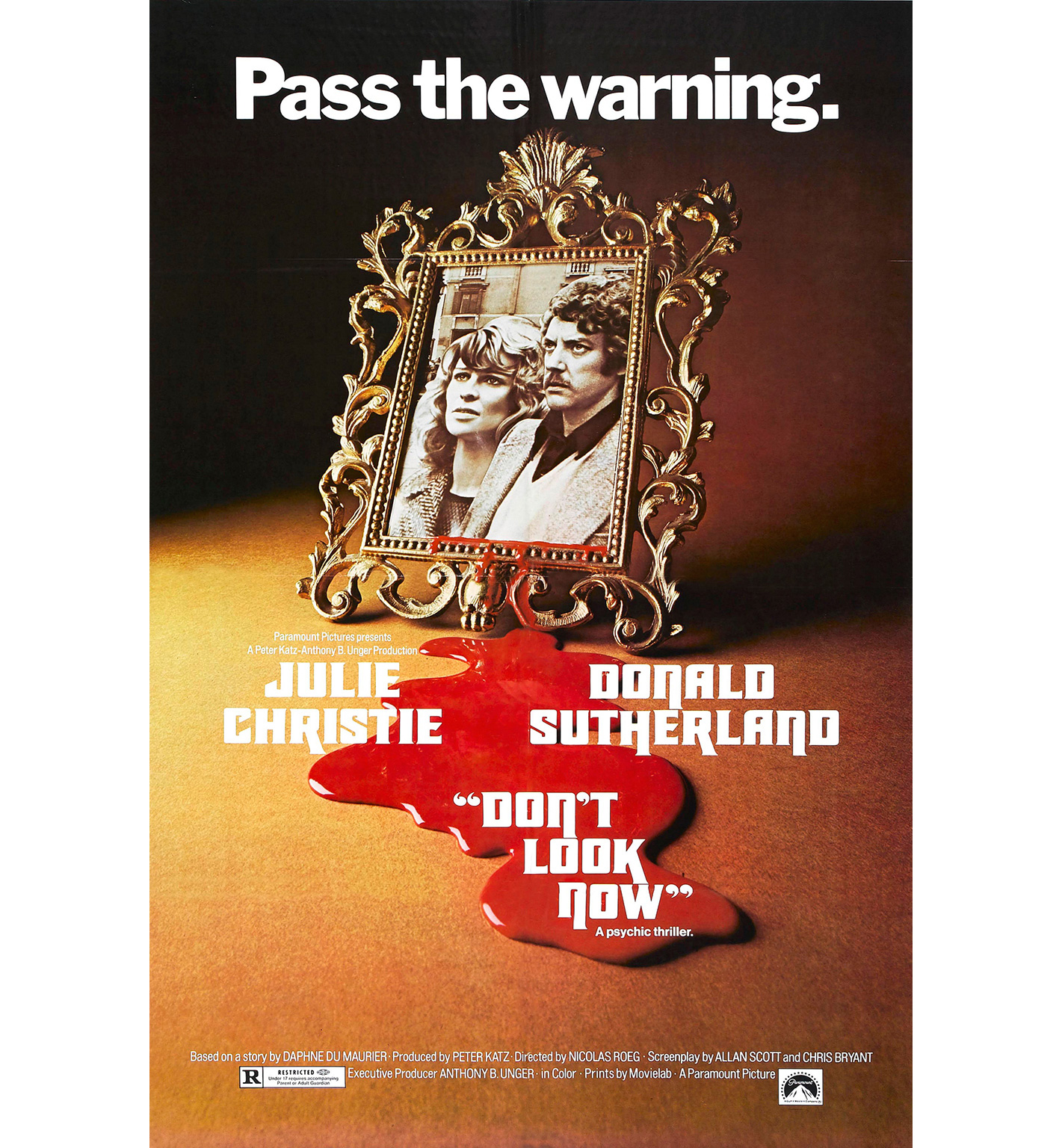

The movie poster hints at the ending without giving anything away. Like John, the audience only finds out at the end of the movie what the “warning” was all along.

Love scene

Perhaps the most celebrated example of this fragmented editing style is the sequence in which John and Laura make love for the first time since Christine died. Roeg makes quick, disjointed cuts between the couple in bed and the two of them dressing for dinner later in the evening. The result is a sex scene unlike any other—intense, touching, melancholic, and comic; and so realistic that many contemporary viewers assumed the sex was real. This is a movie that forces us to look again, to ask ourselves, “Did I really see that?” John cannot see what is in front of him: that he possesses the gift of second sight. He doesn’t believe in psychics, and when Laura tells him that the clairvoyant has “seen” their daughter in Venice, he reacts by getting drunk and angry. Even after he sees Christine’s reflection in a canal, rippling across the water, he refuses to open his mind to the existence of ghosts. In Don’t Look Now, seeing is not believing: you must believe in order to see.

Roeg and his writers, Allan Scott and Chris Bryant, find moments of sly humor in John’s willful “blindness.” When he loses his way in the labyrinthine alleyways of Venice, he pauses beneath an optician’s sign (in the shape of a huge pair of glasses). “Do look now!” it seems to say, but he ignores it and hurries on. In another scene, John is mistaken for a peeping tom while searching for the home of the peculiar sisters. Other characters have no problems navigating the city, but John is forever getting lost and finding himself back where he started. For him, time and space are jumbled up and compressed, just as they are in Roeg’s editing.

“This one who’s blind. She’s the one who can see.”

Laura Baxter / Don’t Look Now

The movie opens with a slow-motion sequence in which John drags Christine’s lifeless body from a pond. It introduces many of the movie’s key motifs, including water and the color red.

Venetian setting

Venice is the perfect backdrop for a horror movie about déjà vu; there are reminders of death and decay around every corner, and its bridges and canals all seem to look alike. Shot on location in and around the Italian vacation destination, Don’t Look Now mostly avoids the tourist traps; St. Mark’s Square, for example, makes a single, easy-to-miss appearance. The movie sticks to the backwaters, creating a trap of its own from a maze of dank passages, churches, and empty hotels.

Much of Roeg’s Venice is unseen: the audience hears cries in the night, a piano playing somewhere nearby, footsteps that echo all around. “Venice is like a city in aspic,” says the blind clairvoyant. “My sister hates it. She says it’s like after a dinner party, and all the guests are dead and gone. Too many shadows.” The camera lingers on dust-sheeted furniture and shuttered windows, suggesting something concealed from view.

The sense of danger intensifies when the audience learns that a serial killer is on the loose. This revelation comes late in the movie, but Roeg leaves a bread-crumb trail of clues leading up to it: the killer is seen in one of John’s photographic slides, hidden in plain sight, in the very first scene; a police inspector doodles a psychotic face as he interviews John at the station. “What is it you fear?” he asks.

The subplot of the murderer adds another layer to the movie’s kaleidoscope, forcing the audience to question everything it has seen so far. Is Christine in fact a ghost or something even more sinister? Do the sisters know more than they are letting on? Eventually, Roeg pulls focus on fate and a truly macabre finale, the kaleidoscope resolving itself into an image of pure Gothic horror.

John follows the red coat on the Calle di Mezzo to the gates of the Palazzo Grimani where he encounters the dwarf.

"The fanciest, most carefully assembled enigma yet put on screen."

Pauline Kael

5001 Nights at the Movies, 1982

Closing montage

Roeg saw his movie as an “exercise in film grammar.” This is never more evident than in its extraordinary climactic sequence, which begins with a séance and ends with a funeral. Don’t Look Now forces John to stare death in the face. Finally, in a fog-chilled Venetian chapel, memories come to life and tragedy descends in a queasy flash of horror and recognition. Roeg crowned the movie with a dizzying montage of moments, images, and overlooked clues from the past 108 minutes of story. Much too late, the audience sees everything.

The danger of falling is ever present. Laura is taken to hospital after a fall in the restaurant. John is nearly killed in a fall, their son is injured in a fall, and Christine died after falling in the lake.

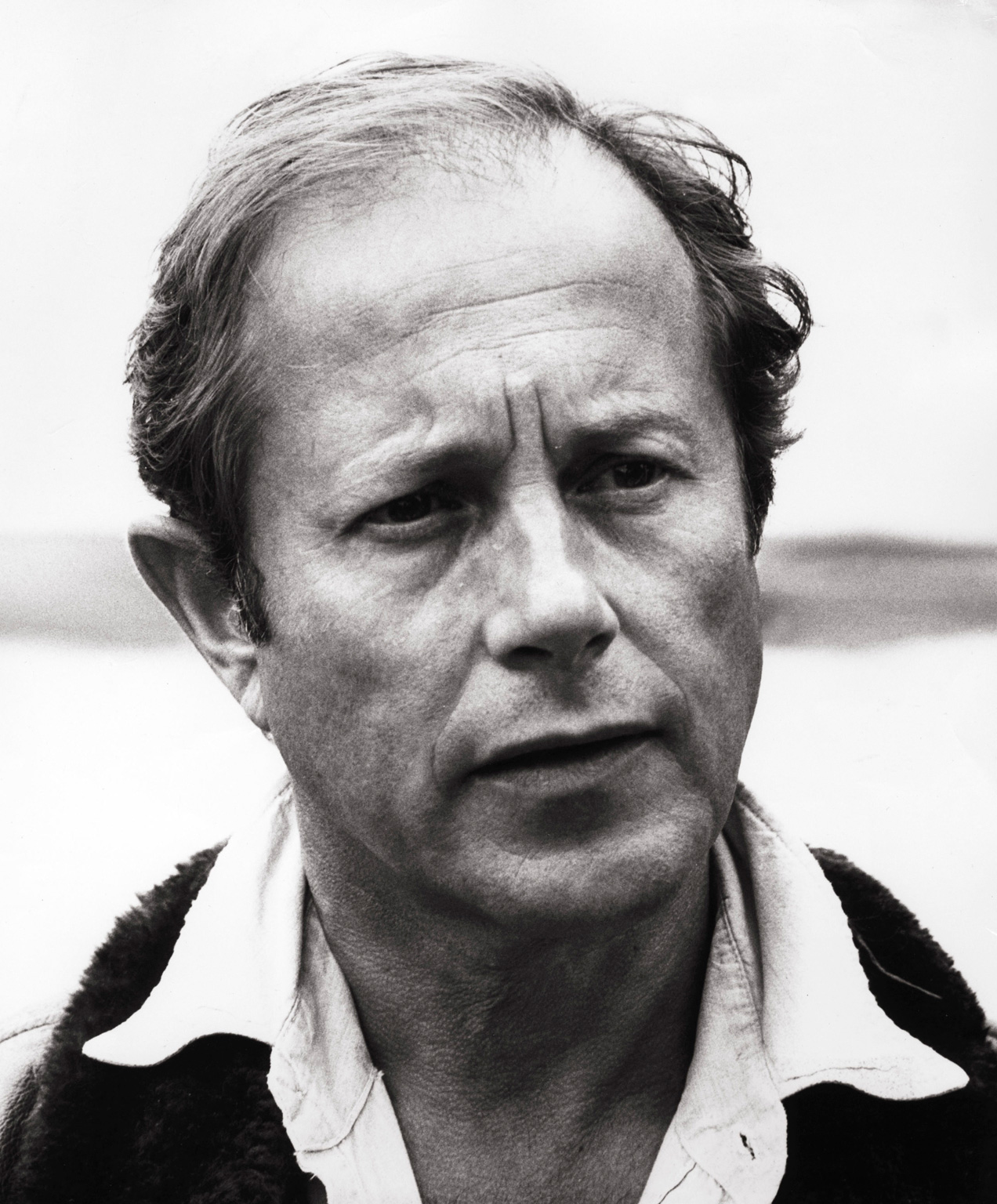

NICOLAS ROEG Director

Roeg first made his mark as the cinematographer for such cult classics as Roger Corman’s The Masque of the Red Death (1964) and François Truffaut’s Fahrenheit 451 (1966). In 1970, he teamed up with the writer and painter Donald Cammell to create Performance, a gangster movie that starred Mick Jagger as a reclusive rock star. Roeg’s next two movies, Walkabout (1971) and Don’t Look Now (1973), continued to explore his fascination with sex, death, and the complex relationship between time and space. Don’t Look Now is often referenced by other filmmakers, but Roeg has directed many fascinating movies since, including The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976).

Key movies

1970 Performance

1971 Walkabout

1973 Don’t Look Now

1976 The Man Who Fell to Earth

What else to watch: Dead of Night (1945) ✵ Peeping Tom (1960) ✵ The Birds (1963) ✵ Rosemary’s Baby (1968) ✵ Death in Venice (1971) ✵ Walkabout (1971) ✵ The Wicker Man (1973) ✵ The Shining (1980)