The Movie Book (Big Ideas Simply Explained) (2016)

IN CONTEXT

GENRE

Black comedy

DIRECTOR

Stanley Kubrick

WRITERS

Stanley Kubrick, Terry Southern (screenplay); Peter George (novel)

STARS

Peter Sellers, George C. Scott, Sterling Hayden, Slim Pickens

BEFORE

1957 In Kubrick’s Paths of Glory, a World War I officer defends his men from false charges.

1962 Lolita is Kubrick’s first collaboration with Peter Sellers.

AFTER

1987 The military’s absurdities are again targeted by Kubrick in Full Metal Jacket.

In 1963, Stanley Kubrick decided to make a movie about the Cold War, which was heating up at the time. The West and its enemies in the Eastern Bloc had been locked in a staring contest for almost two decades, and the superpowers were getting twitchy; if either side blinked, everybody died in a thermonuclear holocaust. This was the basis of “mutually assured destruction,” the military strategy for peace that was beginning to sound like a grim promise of oblivion. The Cuban Missile Crisis had been averted a year before, but only just—surely the apocalypse was coming?

The War Room, vast, impersonal, and punctuated by the ominous circular table with its hovering ring-shaped lighting, was designed by Ken Adam as an underground bunker.

Cold War satire

When Dr. Strangelove opened to an unsuspecting public in January 1964, Kubrick invited audiences to see this doomsday scenario played out on the big screen—and he expected them to laugh. Originally, the filmmaker had intended to produce a straight thriller based on Red Alert, Peter George’s 1958 novel about a US Air Force officer who goes crazy and orders his planes to attack Russia. But, as he worked on the screenplay with writer Terry Southern, Kubrick found the politics of modern warfare too absurd for drama; he felt that the only sane way to get across the insanity of accidental self-destruction was a farce.

In Kubrick and Southern’s screenplay, the plot of Red Alert is given a nightmarish comic spin. The novel’s madman becomes Jack D. Ripper (Sterling Hayden), an American general who blames his sexual impotence on a communist plot to poison the water supply with fluoridation. Ripper sends a fleet of bombers to destroy the Soviet Union, and then sits back to wait for Armageddon.

General “Buck” Turgidson (George C. Scott) imitates a low-flying B52 “frying chickens in a barnyard.”

“Gee, I wish we had one of those Doomsday Machines.”

General Turgidson / Dr. Strangelove

Sexual metaphors

Dr. Strangelove is a political satire, but it’s also a sex comedy about the erotic relationship between men and war—the “strange love” of the title. The movie, which is subtitled How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, opens with the romantic ballad Try A Little Tenderness and ends with Vera Lynn singing We’ll Meet Again over an orgasmic montage of atomic explosions, ignited by the nuclear bomb ridden by Major “King” Kong (Slim Pickens), which sets off the Russians’ Doomsday Device. Kubrick’s stark black-and-white imagery bristles with man-made erections, from nukes, gun turrets, and pistols to General Ripper’s thrusting cigar. “I do not avoid women,” he explains to the RAF’s Group Captain Mandrake (Peter Sellers), blowing mushroom clouds of smoke, “but I do deny them my essence.”

This is a man’s world, in which everyone gets off on mass destruction. The shadowy Dr. Strangelove (Peter Sellers again) wields a tiny cigarette, which may tell us everything we need to know about his motivations. Formerly known as Dr. Merkwürdigliebe, Strangelove is a German émigré scientist. The models for Strangelove were Nazi rocket scientists now in the US, such as Wernher von Braun. He has a mechanical arm with a mind of its own—whenever talk turns to mass slaughter or eugenics, it rises involuntarily in a Nazi salute. Strangelove has trouble keeping this particular erection under control, and at the prospect of the world blowing up, he jumps out of his wheelchair with a shriek of joy. “Mein Führer,” he ejaculates, “I can walk!” He is literally erect: sexually awakened, potent, and about to see his Nazi plan for a supreme race of humans, where there are 10 women for every man, put into action.

There is only one female character in the movie, Tracy Reed, who plays Miss Scott, General Turgidson’s mistress-secretary and also the centerfold “Miss Foreign Affairs” in the June 1962 copy of Playboy, which Major Kong is seen reading in the cockpit at the start of the movie. In what was one of a number of “insider” references throughout the movie, the issue of Foreign Affairs draped over her buttocks contained Henry Kissinger’s article on “Strains on the Alliance.” The mix of sexual and military connotations persist between Miss Scott and General Turgidson. When their tryst is put on hold due to the crisis, she is instructed to wait: “You just start your countdown, and old Bucky’ll be back here before you can say… Blast Off!”

Many of the characters’ names refer to themes of war, sexual obsession, and dominance, from the obvious Jack D. Ripper (prostitute murderer Jack the Ripper) to Ambassador Alexi de Sadesky (Marquis de Sade). The bombs, too, have been named “Hi There” and “Dear John,” signifying the beginning and ending of a romantic relationship.

Dr. Strangelove’s sinister black glove, worn on his errant right hand, was Kubrick’s own, which he wore to handle the hot lights on set.

"Dr. Strangelove outraged the Pentagon, though it was unofficially recognized to be a near-documentary."

Frederic Raphael

The Guardian, 2005

Superpower egos

In addition to Mandrake and Strangelove, the mercurial Sellers plays a third role: President Merkin Muffley (another sexual innuendo), who attempts to manage the crisis from his war room. In this vast, echoing forum, the US leader meets with an all-male cabal of diplomats, soldiers, and special advisers to decide the future of humanity.

The movie’s central comic set piece involves Muffley telephoning Kissoff, the Soviet Premier, to warn him about the imminent attack; Kissoff is drunk at a party, and the conversation descends into petty squabbling. Sellers’ monologue is hilarious, but also terrifying, because the “red telephone” had only recently become a reality. The hotline between Washington and Moscow had been set up in 1963, and Kubrick’s movie nudged the concept toward its logical conclusion: a Cold War reduced to the vying for dominance of two men’s wounded egos. “Of course it’s a friendly call,” Muffley pouts into the receiver, “if it wasn’t friendly then you probably wouldn’t even have gotten it.” These jokes must have chilled the blood of contemporary viewers, and they still unnerve today.

A less sophisticated spat occurs later in the movie, between the gum-chewing General “Buck” Turgidson (George C. Scott) and the Russian ambassador (Peter Bull): the Cold War reduced even further, to a schoolboy scuffle. “Gentlemen, you can’t fight in here,” says a horrified Muffley, “This is the War Room!” It is silly, clever, and, deep down, full of rage. Kubrick clearly hated these characters; the men in Dr. Strangelove are a bunch of clowns, pathetic and deluded, and the director originally intended to end his movie with an epic cream-pie battle. He filmed the sequence, then changed his mind, and swapped the pies for nuclear warheads, in case anyone thought these clowns might be harmless.

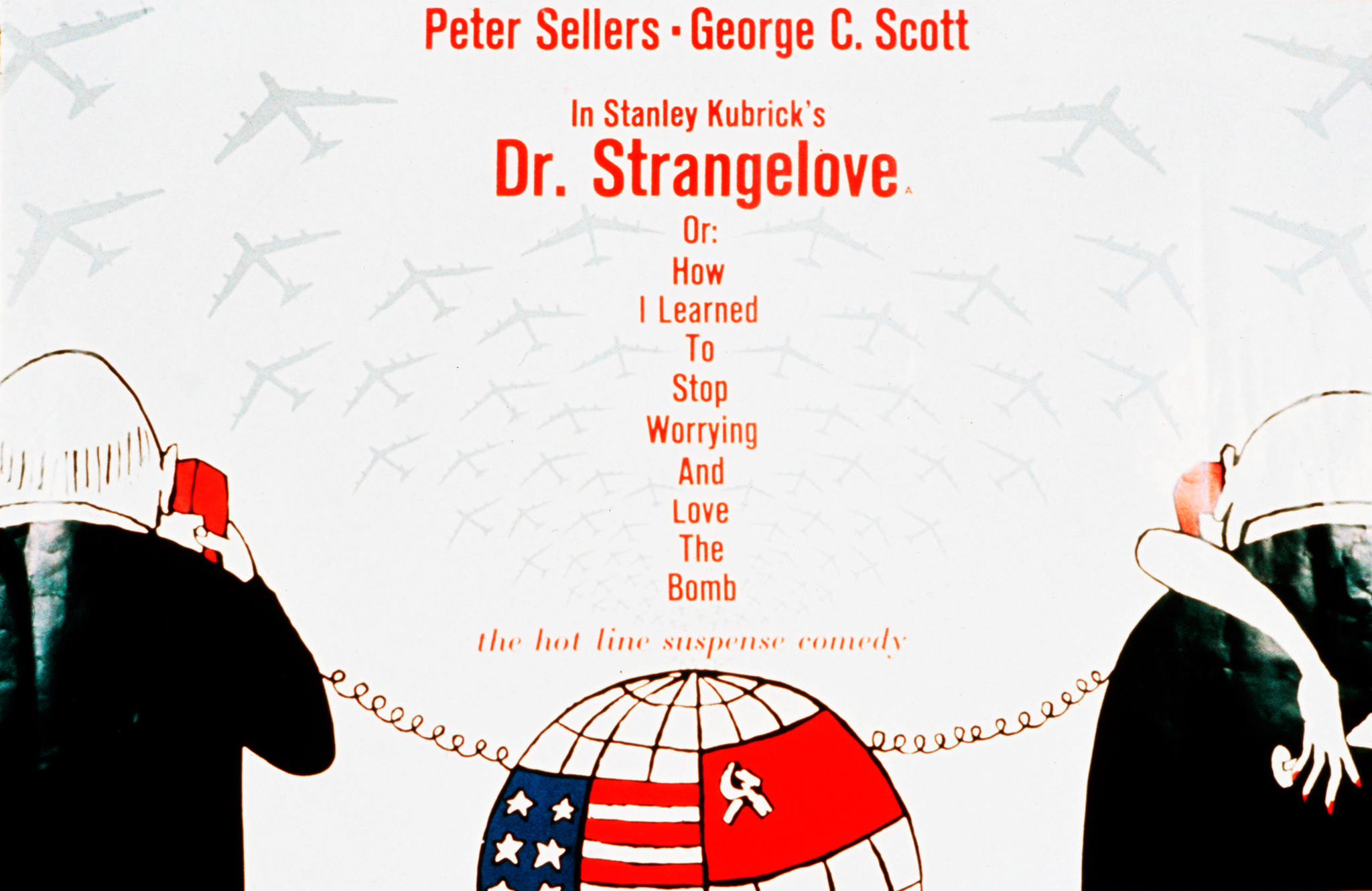

The poster for the movie shows the presidents of the two most powerful countries in the world, who squabble over the telephone like children. They are powerless to prevent the nuclear catastrophe.

“I’m not saying we won’t get our hair mussed. But I do say no more than ten to twenty million killed, tops.”

General Turgidson / Dr. Strangelove

STANLEY KUBRICK Director

Born in New York in 1928, Kubrick spent his early years as a photographer and a chess hustler. These two interests—images and logic—would inform his career as a movie director, which began in 1953 with Fear and Desire. Kubrick cast his analytical eye over several genres—historical epic (Spartacus), comedy (Dr. Strangelove), science fiction (2001: A Space Odyssey), period drama (Barry Lyndon), horror (The Shining)—giving them a unifying theme of human frailty. He was perhaps less interested in humans than he was in machines, not just the hardware of cinema but also society’s obsession with technological progress. His unrealized final project, the science-fiction epic A.I. Artificial Intelligence, would have offered his last word on this subject. It was filmed by Steven Spielberg in 2001, two years after Kubrick’s death.

Key movies

1964 Dr. Strangelove

1968 2001: A Space Odyssey

1971 A Clockwork Orange

1980 The Shining

What else to watch: Paths of Glory (1957) ✵ The Pink Panther (1963) ✵ A Clockwork Orange (1971) ✵ Being There (1979) ✵ The Shining (1980) ✵ The Atomic Café (1982) ✵ Threads (1984)