The Movie Book (Big Ideas Simply Explained) (2016)

IN CONTEXT

GENRE

Drama

DIRECTOR

Yasujirô Ozu

WRITERS

Kôgo Noda, Yasujirô Ozu

STARS

Chishû Ryû, Chieko Higashiyama, Sô Yamamura, Kuniko Miyaki

BEFORE

1949 The first great movie in Ozu’s final period, Late Spring, is an example of shomin-geki, a story of ordinary people’s lives in post-war Japan.

1951 Ozu continues his preoccupation with the state of the Japanese family with Early Summer.

AFTER

1959 In Ozu’s Floating Weeds, a group of kabuki theater actors arrive in a seaside town, where the lead actor meets his son for the first time.

Tokyo Story was made in the wake of the decades of militarism in Japan that culminated in catastrophic defeat in World War II. Ripples from the war can be detected in it, but unlike many Japanese movies of the postwar period, Yasujirô Ozu’s movie remains even-keeled throughout. Its characters go about their lives without fuss, and it ends with a quiet tragedy that mirrors Japan’s somber introspection at the time.

As the title suggests, Tokyo Story is a simple tale. The movie is more a carefully curated collection of moments than a drama, and concerns relations within a family. Shukichi (Chishû Ryû) and Tomi (Chieko Higashiyama) have four children: Kyoko (Kyoko Kagawa), an unmarried daughter who lives with them at home; Keizo (Shiro Osaka), their youngest son, who works in Osaka; Koichi (Sô Yamamura), a doctor living in Tokyo with a wife and two sons of his own; and Shige (Haruko Sugimura), also a Tokyoite, who runs a beauty salon. A fifth child, a son, died in World War II.

The movie depicts Japan at a moment of profound change, but its story of familial disintegration resonated with audiences worldwide.

A journey

Shukichi and Tomi decide to pay a visit to their children in Tokyo and meet their grandchildren for the first time, and embark on a train trip to the hurly-burly of the city. They are unfailingly positive and polite, but viewers sense the pair’s disappointment in the way their offspring have turned out. None of the children make time for their parents in their busy schedules. Indeed, it seems that Noriko (Setsuko Hara), the widow of their dead son, is the only person who cares about them. At one point, the parents are packed off by Koichi to a coastal spa, so that the room in which they are staying can be used for a business meeting.

The children return home for Tomi’s funeral. Over the funeral dinner, the conversation turns into a discussion of the inheritance with almost indecent speed.

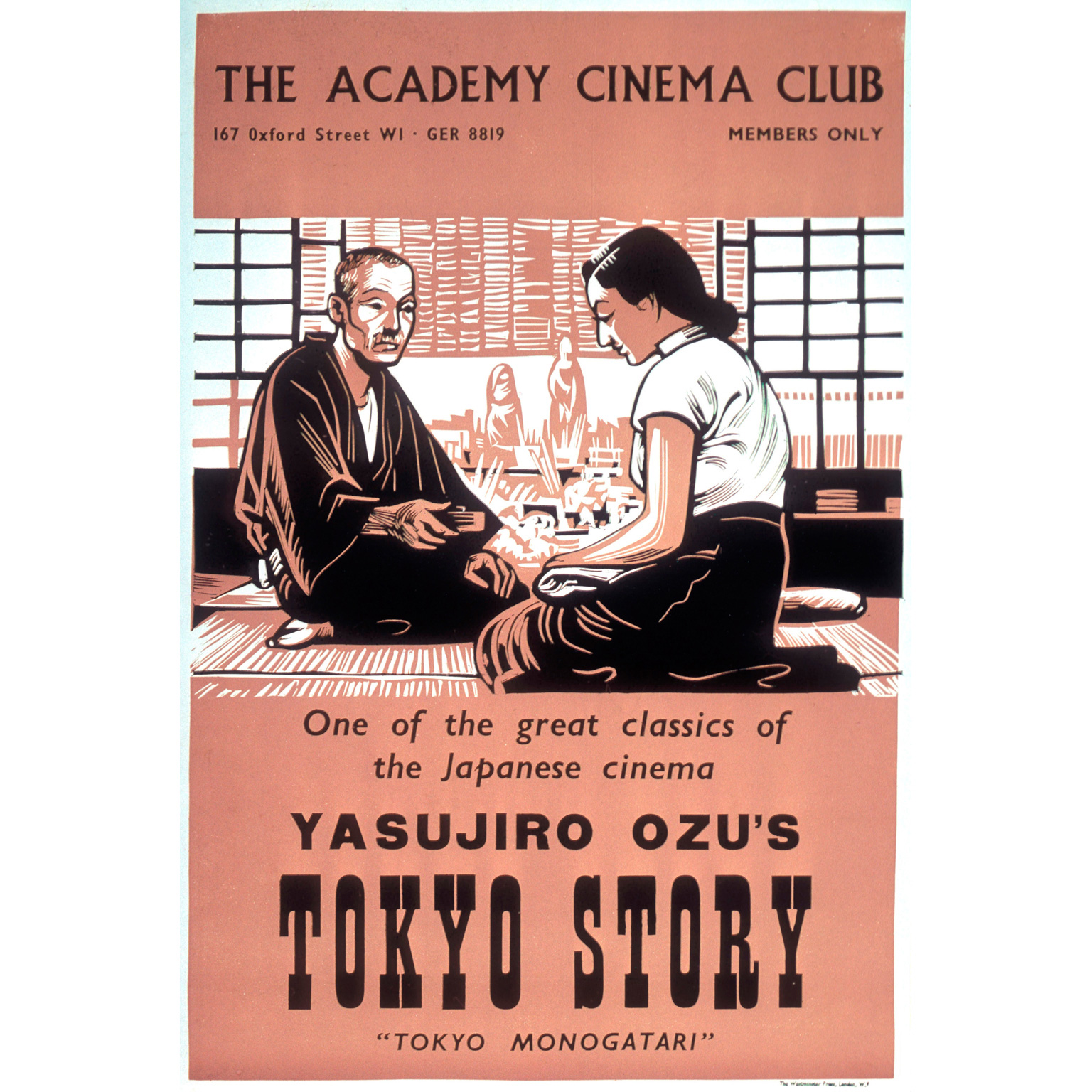

Static observer

This funny-sad odyssey is observed in Ozu’s trademark style: through a static camera positioned low down, at the eye level of a person seated on a tatami mat. Characters come and go, moving in and out of the frame, but Ozu sees everything, as though a silent and invisible observer planted in every scene. The camera’s positioning is all about tradition, just as the story it records is about the mutation of family life and an ancient culture in the age of modernity.

“Let’s go home,” says Shukichi to his wife after a few days. “Yes,” replies Tomi. In their words is an acceptance between them, an acknowledgment that their shared role as parents has become redundant. This sparse exchange is typical of the couple’s interaction in that few words are spoken but much is said. It is also Ozu’s way of telling stories on film: a small and fleeting moment that contains huge significance.

The couple is sitting on a sea wall in their spa gowns. As Tomi gets up, she has a dizzy spell. “It’s because I didn’t sleep well,” she explains to her concerned husband. Shukichi’s face tells us what he is thinking: she is going home to die, which she does a few days later. Now it is the turn of their children to make a journey for the family.

“This place is meant for the younger generation.”

Shukichi / Tokyo Story

YASUJIRÔ OZU Director

Often described as the most Japanese of filmmakers, Yasujirô Ozu is also the most accessible of the great directors to emerge from that country in the postwar period. His unfussy style won him the reputation of a minimalist—but his movies are busy with the rich detail of human life and drama. Between 1927 and 1962, Ozu directed more than 50 features. All of them focused in some way on the changing rhythms of family life in the modern age. His “Noriko Trilogy,” of which Tokyo Story was the last, all starred Setsuko Hara as Noriko.

Key movies

1949 Late Spring

1951 Early Summer

1953 Tokyo Story

What else to watch: Brothers and Sisters of the Toda Family (1941) ✵ There Was a Father (1942) ✵ The Flavor of Green Tea Over Rice (1952) ✵ Tokyo Twilight (1957) ✵ Equinox Flower (1958) ✵ Good Morning (1959) ✵ The End of Summer (1961)