Boogers, Witches, and Haints: Appalachian Ghost Stories: The Foxfire Americana Library - Foxfire Students (2011)

BOOGERS, WITCHES, AND HAINTS

Probably my earliest memories are of the times when the power would go out and we would have to get down the kerosine lamps. My grandmother always used these times to the best advantage by telling ghost stories—or “booger” tales. I don’t remember the tales as such, but I can remember the lamp that lighted only her face as she recalled the choicest horrors of her childhood.

That the people of these mountains should have a rich supply of “haint” tales is not at all surprising. They had conquered the land—but only in a small area around their doors. No matter how friendly the woods seemed in daylight, there were noises and mysterious lights there at night that were hard to ignore if you were out there all alone.

We tape-recorded the following stories in an attempt to let you share a singular mountain experience—a night of ghost tales by a slowly dying fire.

DAVID WILSON

1

To be absolutely truthful, most of the people we talked with did not believe in ghosts or witches or anything of the sort. They had either seen their fears proved false (a white dog, a flapping sheet, natural gas, or the like), or they simply had never had to have them proved false—they just never believed. We met many of them in the course of our wanderings. Here are some of the best of their comments.

MRS. E. H. BROWN: Oh, I’ve heard a number of ghost stories. They come in here and they went out here and I didn’t pay any ’tention. I never have been hainted. I didn’t think I’d ever done anybody any harm that they’d bother me.

I moved t’Highlands and they’uz some people come in tryin’ t’tell me how terrible th’old Methodist Church was haunted there at Scaly there where I lived. Well, I’uz raised there. I let’em tell their tales. They said that you just couldn’t go in that church at night—they’uz th’awfullest thing they ever were in there.

I let’em tell their story, and I laughed at’em. I says, “Well, I’ve been in that church after dark by myself and I didn’t hear a thing.” I said, “I wasn’t a bit afraid.”

There’uz a boy that’d been murdered that’s grew up with me was buried out there, but I never done th’boy no harm, and I didn’t ’spect him t’make any noise and bother me.

And then they thought they would get me. Said, “Just as sure as you pass th’school house about midnight, you’ll see a little girl and a little boy walkin’ that rock walk.”

“Well,” I said, “I’ve passed there alone many nights about midnight and I never did see anything.” That was just a fancy someone had told. Why, I passed that place numbers of nights. I didn’t see nothin’. I believe most a’that is imagination. I say imagination, or maybe a guilty conscience. Then you might see somethin’. I wouldn’t be surprised. If you’d done some dirty deed or murdered somebody or something, why I wouldn’t be surprised if they wouldn’t imagine they saw something.

But I never experienced no such thing. Only thing I was ever afraid of was a dog or a snake.

DANIEL MANOUS: No, I don’t think there’s anything like that. Do you? I don’t think so. I think that’s th’imagination. You think on a thing till you think it’s real.

I used to hear my grandfather tell one about when he’uz a boy. They’uz a cemetery right close to where he lived, and he could hear a baby cryin’ every night over at th’cemetery.

He’uz scared and didn’t know what t’think about it and told one of th’neighbors. Said, “I heard a baby cry over yonder at th’cemetery every night. I didn’t go about it.” Said, “I’m afraid to. Are you afraid to go over there?”

He said, “No, I’m not afraid to go over there.”

Grandpa says, “You come over t’my house tonight. If that baby cries, if you’ll go over there and see what it is, I’ll give you ten dollars.”

So he came over then that night, y’know, and waited till seven o’clock. Said, “All right. If you’re not ’fraid t’go, now’s th’time t’go.”

That man just took off and went over there, and they’uz a big basket sittin’ on top a’th’tombstone, and they’uz a baby in it. Little baby boy. He just went and picked up th’basket, went on back and took it to him and said, “It’s a baby.”

He’d been a’hearin’ th’baby for several nights he claimed. He kept that baby and raised it, and it went by th’name a’ Billy Tombs—after th’tombstone. That was actually th’truth. I’ve heard my grandpa say that he’d seen th’boy a many a time. Billy Tombs.

The Bible preaches that th’dead don’t know anything at all. After any person dies, why they don’t know anything. They don’t have any thoughts, don’t know a thing in th’world.

Well, they couldn’t come back here. They couldn’t come back and cause trouble and bother th’livin’ because they can’t get back. They’re dead. They don’t know anything.

If you don’t believe th’Bible, you just as well not believe nothin’. If it didn’t teach that, y’might have somethin’ t’base it on, y’see. But since they don’t know anything, how could they come back? ’Cause they’d have t’be doin’ a little thinkin’r’somethin’r’nother before they could get back and trouble anybody’r’anything.

They’s mediums that say they could talk t’th’dead and all that. I don’t believe that. That’s just a evil spirit. Really, I don’t believe in’em. They’s nothin’ t’base it on. They’s no foundation. Cain’t build a house without no foundation. Th’Bible destroys all th’foundation. If somethin’ dies, it’s gone—don’t know a thing in th’world. You kin find th’stories, but there ain’t no foundation for’em. That’s what I call a myth. Just not reality.

MARY CARPENTER: There’s a place over yonder at Jim Branch—they had been people said they’s seen balls of fire big as these old-timey washpots roll th’road there. I forgot who it was told me that they’uz comin’ there one night and said they was a big ball of fire. And they said they hit Frank Kelly’s field and cut out across through th’field and wouldn’t pass it.

HOYT THOMAS: I had friends treed a possum one night, and said they seen a ball a’fire that gave enough light till they seen how t’get that possum out a’that tree.

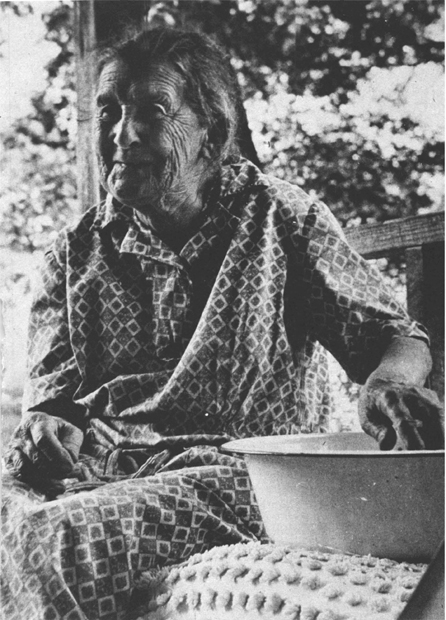

ILLUSTRATION 1 Annie Perry

And then one night last winter we seen a light, but it was a weather satellite put up in fall that was burnin’ up. It just looked like a extry moon. It had kind of a purple-like glow around it. Didn’t last but a few minutes till it was gone. Then it trailed off in a cloud of smoke.

And one night it just looked like th’world was afire back in there. Like a big forest fire, y’know. And it come on around, and at twelve o’clock it went right square up in th’middle of th’sky and made a question mark. Just as pretty a question mark as you ever looked at.

ANNIE PERRY: I don’t know nothin’ about ghosts. In fact, I never was brought up t’hear ghost tales. My daddy said not t’tell children ghost tales. Said it’ud make’em afraid. Well, I’m not afraid, but I tell you I had a sister that wouldn’t open a door an’ go out on th’porch an’ get a drink a’water at th’well. She’uz just afraid a’th’dark.

They’s no such thing as a haint. It’s not a thing in th’world but imagination. They just imagine they hear these things and they don’t hear’em at all.

Now this is not a hainted tale—this is true. I’uz seven years old when I started school. Had t’go through these woods over here, and ever’body thought they’uz haints in th’woods.

And th’neighbors, they had lots a’big old brood sows. And if you caught a pig’r’made a pig squeal, they’d bite you. And they’d say, “Now, Annie, don’t you get out there on th’side a’th’road (them pigs’uz on th’side a’th’road), an’ go through there or them old sows’ll eat you up.”

Well, they had me afraid a’hogs.

I’d have t’go by m’self through those woods over there. I’d look way out here and way out there. There wouldn’t be a thing in th’world. Directly I saw a thing that looked like a hog. I had t’go by it and I was skeered. And there wasn’t a thing in th’world. Not a thing. They wasn’t a hog within a mile a’there—just some old stumps a’lyin’ there. But I guess it looked like a hog t’me. Imagination. That’s so now. They skeered me with hogs. And I’d look way out an’ I’d see somethin’ and I’d make a hog out of it.

Now that’s th’way ghost tales get started. Ain’t no ghosts.

LAWTON BROOKS: ’Bout two mile and a half out a’Hayesville, there kind’a in a bend in th’road is where a man was killed and just shoved out onta this big old white rock by th’side a’th’road. And he died and left blood a’settin’ on th’rock. That blood wouldn’t wash off. Stayed there a long time. An’ ever’body passed through there got scared, y’know, seein’ blood on th’rock where that man just fell out and died.

’Course people got their nerves up and got scared about it and they’d see ghosts. Some of’em said somethin’ would be gettin’ on behind their mules or horses an’ ride with’em an’ spook their animals an’ make’em jump around scaired and crazy like. People was really scaired t’go by that big white rock ’cause so many people says somethin’ would get on their animal an’ aggravate th’dickens out’a’em.

I was a’courtin’ up there, and I had t’come by there. ’Course I could’a went around, but if I went around it would’a been further out’a my way, and I decided t’go by it. It was a’rainin’ that night, and I’d just take th’near cut and go down through there.

When I got pretty close t’where that rock was, m’horse got scaired and wouldn’t budge nary an inch. Just bowed right up, front legs stiff like boards. I teched’im wi’m’spur and he jumped over t’other side th’road. Took a step’r’two and bowed up again, and I could feel’im a’shakin’ a little even.

’Bout that time I saw somethin’ white comin’ off th’bank right down t’where that rock was at and stopped. I thought t’myself, “You got me!” I just knowed that’d ’bout done me in.

So m’horse, I think he found out before I did what that thing was, and he just commenced walkin’ along and walked right up next t’it. I got me a match out’a m’coat pocket—they wasn’t no things like flashlights in them days—and I struck me a match, and there set a big white dog—big old white shepherd dog a’settin’ there in a ditch.

And if I’d a’went on and hadn’t a’never discovered what that was, I’d a’always said I seen a ghost. But I found out what it was.

ETHEL CORN: They call them balls’a’fire jack-a’lanterns. It’s kind of a round-lookin’ thing, an’hit’ll come and they’ll play up—they’ll go down low t’th’ground and high up. And they’re see’d always over here on what they call th’Chainey Hill. And some said hit was from mineral. They’s a vein a’minerals goes through there. And they’d rise and they’d go up, and they’re pretty good-sized lights, and they’re playin’ all over th’bottoms down below there. And sometimes they’ll go away-y-y up and then back down.

I’d been out a’plowin’, and I’uz a’wantin’ t’get th’bottom plowed out. And I plowed—hit was a dusky dark when I got in. And I went t’put up th’horse and got th’corn and went t’feed her, and right at th’back of th’stable they was jest a big light rose down right at th’back of th’stables in th’swamp.

And hit kept a’goin’ higher and higher. I was young—I wadn’t plumb grown—and I was awful cowardly, and I throwed th’corn through a crack in th’stable—I didn’t put it in th’trough—and I run and I run and I never knowed what it was. I didn’t take time t’see how high it went. I run!

And Andy Burrell’uz goin’ up th’branch home one night. It’uz in th’winter time an’ right cold and th’wind’uz a’blowin’ right hard; and it got t’blowin’ an’floppin’ his tie back over his shoulder. And he never thought of it bein’ his tie, and he run about a quarter mile up th’mountain till he just give completely out.

And when he did, he found out hit was his tie that’uz a’doin’ th’floppin’ and makin’ th’rackets. He’uz scared, and he took a hard race from it!

MINYARD CONNER: This boy that lived way back in th’woods had t’go hunt his cows ever’ evenin’. There was a big tree beside th’road. He’d drive his cows in there and they’d be somethin’ hangin’ down from th’limb up there on th’tree. Couldn’t tell what it was. He said it would just be hangin’ there. Just nearly dusk.

And he had some more boy friends that lived pretty close. He told these other boys about it. They didn’t believe him. And he told’em a certain time of th’evenin’ it’ud be hangin’ there. Said it wouldn’t be hangin’ there when th’sun was shinin’r’anything. It would be right late of evenin’. He told’em t’come a certain time.

Well, th’night th’boys was t’come, he went up there. He kept watchin’ that limb t’see if anything was a’hangin’ there. He’d bet some money, and he’d lose his money if they wasn’t. Well, they wasn’t, so he just decided he’d get out and climb th’tree and hang down himself.

’Bout that time, here they come around th’curve, y’know. He’uz a’hangin’ down yonder. He’d slipped down on th’limb and he’uz a’hangin’ down there.

Th’boys come up and looked around. Said, “Well, he told th’truth. But he said there’uz just one. There’s two of’em.” And that boy kept turnin’ his head around, y’know, and kept turnin’ his head around. He turned around and seen that’un hangin’ right beside him! He just turn loose and here he went! And when he hit th’ground, th’boys broke and run.

Well, he jumped up and took atter’em. He said, “Wait there, boys. I’m one of you!”

One said t’th’other’n—they was a’runnin’ right t’gether said, “What did he say?”

“He said, ‘Wait there, boys. I’m gonna have one of you!’ ”

That’s th’way them ghost stories gets started.

WILL ZOELLNER: I didn’t think much a’ghosts then. We told a lot a’tales—pulled off some stunts on people—done lots a’foolishness around about that.

One time we sent a couple a’girls t’get some water—needed some water. It was Christmas I think it was. They went out t’th’spring, and when they got out there, there was two fellas had a bed sheet wrapped around’em.

Well, th’girls filled their jugs—one of’em had th’jug done full and th’other had it ’bout nearly full. Th’moon was shinin’ just as bright, and they’uz about four’r’five inches a’snow on th’ground—had been fer several days. And them fellas just popped out acrost th’spring on th’other side.

Those girls, they just fell down like dead. By God, I thought we’d never get’em back t’th’house. We toted’em and ruffed’em around. Even got a rubbin’ doctor from Pine Mountain when they come to.

Gosh, they never played that game n’more. They’uz just scared t’death. Them girls—I heard their hearts a’beatin’, and they groaned a lettle bit onct’ in a while. They’uz just limber as rags!

MARGARET NORTON: They say th’best way t’keep from gettin’ scared when y’hear somethin’ is t’find out what it is. Go right on and find out what it is, and then you’ll know. It’s usually a animal’r’somethin’ like that. Maybe a possum in a tree.

2

There were, however, a surprising number of contacts who had seen, or whose relatives or close friends had seen, phenomena that were inexplicable to them except in supernatural terms. Most believe unshakably that haints, boogers, and evil spirits walk the land, and after hearing their stories, one wonders.

AUNT NORA GARLAND: There was about thirteen couples of us, and we took a notion to walk out plumb to the Mountain City Blue Heights Church to a box supper.

Well, we all were coming, and there was about thirteen couples I guess, and we started back up th’mountain and in th’dead of winter. Awful cold, but y’know we were young and didn’t care much, and we were all coupled up together, and me and m’husband; of course—we weren’t married then.

But there was a little girl there. And there was a family that lived about a mile and a half from th’church back up th’mountain on that old road, and they was pretty well-to-do people. And I thought strange about them a’lettin’ that child go—them leavin’ that child at th’church.

So we started from th’church and this little child—it looked t’be about four year old and it was barefooted and it had on a white dress and a little band in it like they use t’make’em, and it had blond colored hair and curls plumb down t’its shoulders—it walked right at my heels every step up that mountain.

And I just thought ever’ one of th’rest of’em seen it, and I just thought these well-to-do people had just left this child in church. Just went off and left it t’sleep there.

It kept right at my heels. It didn’t walk at th’side a’my husband. It walked right at my heels all th’way up that mountain to a branch. And just before we got t’th’branch, why that child fell down and spread out its arms thataway and was just as gone as gone ever be. I said, “Lord have mercy,” I said t’my boyfriend. The instant I said that, there wasn’t a thing there a bit more than nothing in this world.

That’s th’reason I believe in ghosts.

I wouldn’t have found out such a thing as that if I hadn’t see’d it with my own eyes. But of course I wasn’t a bit afraid, y’know, because they’uz about thirteen couples along in front. But that little’n had walked right at my heels ever’ step up that mountain till we got t’th’branch, and my mother always said that a ghost wouldn’t cross water.

Her and my father used t’live right on up above there in a house, and she said every morning there was a naked baby sittin’ on th’chimney. She’s told us that so many times, but I didn’t see that. I’m just’a’tellin’ y’what I see’d. It might have been th’same thing, but this child was dressed in white. But I wouldn’t have thought of a ghost, and hadn’t thought of one, if I hadn’t see’d it with my own eyes.

JIM EDMONDS: When my gran’daddy was a little boy, he had a aunt that died. She run a old-time loom. Worked herself t’death.

She died, and th’old man tore th’loom house down where she worked. Wanted t’get it out a’th’way. And he was goin’ a’courtin’ three weeks after she died—courtin’ with another woman. Gran’daddy said he heard th’boards a’rattlin’ just like th’old loom a’runnin’. Heard th’loom a’rattlin’. Said they had a big fire a’goin’—a big blaze—and she walked up t’th’door.

Th’little baby—her baby—they had t’hold him to keep him from goin’ to her. Kept sayin’, “There’s Mommy! There’s Mommy!”

And my mother would tell them witch tales. My mother said that her grandfather moved from South Carolina to Townes County. He drunk a lot and weren’t scared of nothin’.

They were lookin’ for a place t’camp, and they asked this feller. He said, “Go t’th’second branch. Don’t stop at th’first. Can’t stay there. It’s hainted.”

He said he was goin’ t’stay there. Weren’t a bit scared. They fixed their camp, got their supper, and went to bed; but he was up. He was a’feelin’ good. Heard someone comin’—like a wagon. Looked down and saw it a’comin’, and just like a big white sheet over th’wagon. Just a’rattlin’.

The old man just hollered at it, but it didn’t go very far before he heard it comin’ back, so he hollered at it again. He got t’hollerin’ at it and cussin’ it—even got out his knife t’cut at it—but you can’t hit’em. That thing faded up and down th’road all night.

Somebody been killed. That’s th’reason for it.

And old Billy Jesse claimed he was a witch. Ol’Gran’daddy couldn’t shoot a thing. Somebody put a spell on his gun. He went over to Billy Jesse t’take th’spell off. He lived in what they call Bitter Mountain Cove. Told him he wanted him t’take th’spell off him. Somebody had witched his gun.

So Billy loaded that gun and went t’every corner of th’house and shot sayin’, “Hurrah fer th’Devil!” Run t’every corner and shot—never did load it but once—hollerin’, “Hurrah fer th’Devil!”

Billy then said, “Now, th’next thing you will see will be a great covey of quail. Now don’t you shoot at nothin’. Then th’next thing you see will be a big buck. You can kill him. Just shoot nothin’ else.”

Gran’daddy done just like he told him, and here come a big drove a’birds. He just held still. He went on and there was this big ol’buck. Shot and killed him. Th’spell was off his gun.

There used t’be more ghosts then than now.

LAWRENCE MOFFITT: I heard of ghosts but I never did believe. But I lived one time down here, I’ll tell you that, talkin’ about ghosts. I don’t know what that was and never did know.

I moved down t’Maysville, Georgia. The man I rented from said there’uz a house below there that was hainted—an old house—and nobody wouldn’t go into it.

Well, th’first night I moved into this house (not th’hainted one) there’uz a racket on th’porch just like you was a’draggin’ a big chain. Well, that would come right on through that house, and there was a side-box kitchen we called it, on th’far side. Well, that would come through every night. Never missed a night.

I’d get up and sit on th’hearth, and had a flashlight. Never could see anything in th’world, but you could hear it just as plain as you can hear me a’talkin’ to you.

Well, I wasn’t used t’nothin’ like that. I talked t’th’man I rented from there. I said, “What’s th’matter? Is this house hainted? You told me th’lower one down there yonder was, but is this one too?”

“Well,” he said, “I’ll tell you. There was a man killed here. You’ve probably seen th’stains there on the plank there on th’wall in th’kitchen.”

I said that I had, but I didn’t know what it was.

“That’s where a man was killed, and ever since, this racket has come through th’house.”

Well, I stayed there six months. There for a week or two, I couldn’t sleep. I was tryin’ t’find out what it was. The minute th’light would come on, that stopped. You didn’t hear nothin’. You put that light out and you’d hear that. It’d come every night at nine o’clock as long as I stayed there. But I got used t’it. I got t’where it didn’t bother me a bit in th’world.

But now t’start with, if I’d had a way, I’d a’come back home!

OSHIE HOLT DILLARD: Way over in North Carolina somewheres, they was a Indian cave when Grandpa Harkins was just a young man. And they thought this Indian went t’th’cave every day—or at least once a week. And they was a white man which slipped around after him for three days and nights until he got a chance to shoot him; and he killed him and got his waybill that was printed on a deer skin.

And he went up there, come by this old farmer’s house and wanted to borrow his mattock. And th’old farmer said, “If you’ll wait till I get my hogs fed, I’ll go wi’ya’.”

And he said, “I don’t want y’t’go!”

And th’farmer said, “Well, th’mattock is a’settin’ out there under th’smokehouse shed. You can just go and pick it up.” And he said, “Take good care of it and bring it back. It’s all I got.”

Said way over in th’evenin’ after they got back from church, th’farmer thought about th’man. Thought he might of found some gold’r’somethin’. He’uz a’lookin’ up through th’field th’way that man had left that mornin’, and said he seen somebody wanderin’ around up there. Said th’farmer went up there and said that man was just as gray-headed as he could be and didn’t have a lick of sense—didn’t even know how t’go home—couldn’t even see. Said he went back and got some help t’carry him home, and th’man lived three days and three nights and died. He never spoke a word.

Th’farmer wanted t’go back and get his mattock—y’know, th’news got out all over North Carolina over in there—and he had t’have his old mattock t’farm with, so he went back up there with a whole bunch a’people. They said, “We’ll dig this mountainside down [looking for gold].”

He said, “You can dig it down if you want to, but I’m gittin’ my mattock and gittin’ out of here.”

So they went t’diggin’, y’know, and laid their coats off. And it sounded like ten thousand freight trains comin’ off th’bluffs. And they was a big old locust tree standin’ there, and said ever’ limb and th’bark fell off of it. And they run off and left their coats.

Grandpa said nobody had ever been back to it. Now he said that was th’real truth.

LAWTON BROOKS: Bob Meeks was his name, and he was a’workin’ somewhere in Tennessee over there. He come through by Benton while they didn’t have th’road then, and he had t’come across that mountain. Now I don’t know whether it was Frog Mountain, whether that was th’name or not. But anyway, there was twenty-two mile there that there wadn’t no houses on it—and steep and twisty, my Lord.

And it was late in th’night. His wife had a’called him. Some of his kids got sick, and he had t’come in. And he’uz a comin’ along up that mountain, and he said he come around a curve and he seen this thing. Said it’uz th’biggest man he ever saw.

The man stepped out of a water ditch by th’side of th’road, and said he just leaned over a little, and as he come by he just stepped on th’runnin’ board, reached down, opened th’door, got in, set down, and looked him over. It was a old Model T, and th’way it was goin’ it didn’t make much more time than a man walkin’.

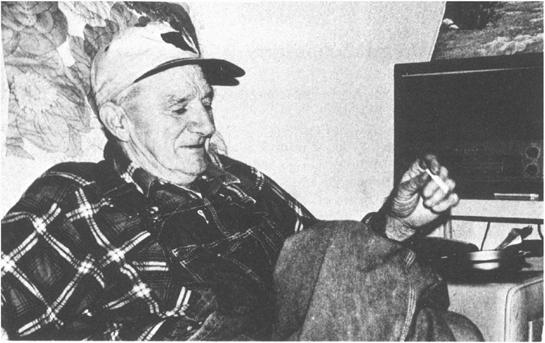

ILLUSTRATION 2 Lawton Brooks

And he said he looked at that thing’s hands and that’s what he couldn’t figure out. Says hit’s fingers, one of’em was as long as two of his’n if they was put together, and as big again around. He said he had awful big arms, and on top of his hands was just as hairy plumb on down toward his fingers. His fingers was th’longest he’d seen on anybody. Must have been ten inches long.

He said he spoke t’him and he never did speak back. He said he didn’t know whether he was gonna do anything t’him or not. He said he knowed he was big enough. They wadn’t nothin’ he could’a done about it. They wadn’t no need a’gettin’ scared because that man could’a reached plumb around him one-handed. Big tall man—all hairy.

Said he had a beard way down, an’ face hairy, an’ said he was a kind’a’nasty-lookin’ old man. Said he looked as old as th’hills.

Said he never got a sound out’a’him. He could hear him a’gettin’ his breath.

And he said he rode at least three mile with him, and he wondered if this thing was goin’ plumb t’Ducktown with him. An’ he was goin’ around another curve, an’ said that thing—man, what’ere it was—he just stepped out. And said he looked back and it’uz just a’standin’ there in th’road.

Said he was th’ungodliest man he ever did see all th’days of his life. He said people might not believe him, but he said it’uz th’truth.

Now I believe it, ’cause I don’t believe Bob’d tell a lie. He was a man never got excited about nothin’.

And after that man got out, Bob said he just kept drivin’ on.

And me and Walter Coleman and George went a’possum huntin’. Now that’s th’only thing ever I did that I never found out what it was. Now I didn’t find out what that was now, I’ll be fair with’y’.

We left, and it sounded like somebody a’takin’ a fit. Jest like somebody a’cryin’—hurtin’ awful bad. An’ it jest commenced when we walked t’where a dog treed a possum out on th’ridge right on’t’th’Hia-wassee River.

An’ we jest went out there t’get a possum, y’know, and when we went out there, by gosh, we just walked around t’th’end a’this old big log there—jest got a little bit past it—an’ somethin’ commenced.

Walter said, “Lawton?” Says, “What in th’world is that?”

An’ I said, “I don’t know, but,” I says, “ain’t that a pitiful noise? That’s somebody or somethin’r’nother hurtin’.”

So we took our old lantern then and walked around th’log. Plumb around it. Come back t’th’big old stump there where th’tree had been sawed off. We looked at th’stump. It wasn’t holler. Looked in th’end of th’log. It wasn’t holler. Well, I went up t’side of th’log with m’lan-tern. Shined th’light along it. Couldn’t see no hole in th’log on either side of it. It still sounded like somebody a’cryin’ and moanin’ under th’log.

And we started a little away from th’log to where it sounded like it was comin’ from now, and then it sounded like it’uz right back there at th’log. And then we’d start off out t’th’log again and it’ud be comin’ from a little away from th’log. And then it commenced there right there at th’log.

And we never did find out what it was. We left there—I mean, we left—old George an’ Walter an’ me. We started off that mountain away from all that moanin’ with nary a possum—into a field (Old Man Smith’s field)—and we run right into a wire fence that we didn’t know was there. Way we went flyin’, when we hit that fence it scared th’daylights out’a us.

That was th’only thing I ever heard I never did find out what it was. Why, I wasn’t skeered s’bad, but I wasn’t gonna stay and them boys run off and leave me! They wouldn’t stay wi’me, and I sure wasn’t gonna’ stay up there an’ listen t’that thing by m’self.

So we didn’t take time t’get any possum!

MRS. MARY CARPENTER: I’ve heard Mama tell about th’one my daddy saw one time. Said that there was a preacher, and there was a forks of a road somewhere near a church I believe it was.

And he said that hit was about ever’ evenin’ about sundown that you could go there, and there’uz a woman that—she was so high up in th’air that she looked like she was on a quilting frame—just high up. And she had on a long black dress and she’uz just a’walkin’ along, and it rustled like leaves a’rattlin’, y’know, as she walked.

My daddy and another man, they worked for Earl Hudson at a sawmill, and they said they’uz comin’ in one night and it was a’rainin’, and they was a’ridin’ them mules on in home.

And that man said to my daddy, said, “I’d like t’see that preacher’s ghost tonight, wouldn’t you? While it’s dark and rainin’?”

Said my daddy said to him, “Well, yonder she comes!”

Said they went on—just kep’ a’ridin’—and Papa said to him, “You ride on one side a’th’road and I’ll ride on th’other and let her come between us, and we’ll see what she looks like.”

And so they did. They reined th’mules over and let her come right in between’em. Said he said t’him, “Let’s foller and see where she’s a’goin’.”

Said it was just a’pourin’ th’rain down, and said they turned th’mules around and followed about a half a mile back out th’road, and said there was just a curve in th’road—a little ridge. And said she just riz and flew over that ridge and they didn’t ever know where she went.

Now is that th’kind of haint tale y’want?

Well, all right. Now there’s a place down next t’my brother’s that they’ve seen things down there on that hill. My husband said they’uz a’goin’ out through there one night—him and Lawrence Talley I believe it was. They’d been t’church up here t’th’Flats to a Holiness meetin’, and they was a’goin’ down Mud Creek goin’ back home.

And he said they was goin’ up along there, and he said he didn’t know what it was. It didn’t say a thing in th’world. But somethin’ just hit them. It was as cold as ice, and he said they just begin t’shiver and shake.

And he said Lawrence said, “Are you cold?”

And he said he was just about t’freeze t’death, and it was in th’summertime.

And he said, “Well, I am too.” Says, “Seems like there’s ice all over me!”

And John said, “Well, seems th’same thing t’me.”

He says, “Let’s run.”

And John says, “I can’t run.”

He said, “I don’t guess I could either.”

And said it just jumped off of’em just like that, whatever it was, and went away.

He said there’s people said they’uz haints out there.

And there at my brother’s right across th’creek—you’ve been over there on Kelly’s Creek up there where Jim Taylor lives—there’s a Mason woman lives over there. She said she’d seen a little baby out there that was flyin’—had wings. And she said it came up out of her garden more than once, and she’d be out there on th’back porch up in th’evenin’ doin’ her night work, and she said it would rise up with wings like a little angel—a baby.

And I know she seen somethin’ one time, fer because her husband’s [Frank’s] daddy lived over on Germany and he was sick—bad sick. And so Frank—he’d went t’see his daddy. They were lookin’ fer him t’die.

And she had a hog pen out in th’woods there, out toward our house, and she began t’scream. And Mama hollered t’me t’run over there fer somethin’s th’matter. She may be snakebit.

Well, I went a’runnin’ just as hard as I could, and Dad, he went a’runnin’ over there. And you know, she’d fainted ’fore th’time we got over there.

By th’time we brought her to, she said there was a man there at her hog pen with a white shirt on and no head! Blood was all over his white shirt.

Gran’pa said they moved one time—said Mama was a little girl then. And he said they got moved all but their chickens, and he had t’go back and catch them after dark.

So he got him some sacks t’put his chickens in and went back t’th’place he’d moved from and caught his chickens up and tied’em and put’em in a sack. He was ridin’ a mule.

He had some slung across his saddle—some on one side and some on th’other—and he was comin’ along, and all at once there was somethin’ in th’road. Said it looked like somebody in th’moonlight.

Said he said, “Whoa” t’th’mule. Said “Is anything th’matter?” And said it looked like a log. Said it started rollin’ toward his mule, and his mule started runnin’ back’erds with’im. Said it just rolled so far and stopped, and it rolled back up th’road.

Said he started back up th’road with his mule—back up through there—and said it’d come back toward him when he’d start.

Said he made two or three trips like that and decided it wasn’t goin’ t’get out of th’road and let him by, and said th’mule was afraid of’im; and so he just laid th’fence down—a rail fence—and let his mule run through th’pasture and come back out, and laid down th’fence again, and passed that place.

And Gran’pa said one time him and Uncle Dave was goin’ home from a dance, and as they come around there where a pond was, why they heard something’ a’sayin’, “Oh Lordy! Oh Lordy!” Takin’ on pitiful.

Gran’pa said he was scared—and said he was little—and he grabbed Uncle Dave by th’coat and said, “Dave, don’t you run!”

He said “I ain’t a’goin’ to. I’m goin’t’stay here. It’s risin’, whatever it is.”

And said somethin’ come up out of the water with th’moon a’shinin’. Said you could see it like a white sheet. Said it had four corners, and it just kept a’goin’ on up, and it was just takin’ on th’pitifulest. Said it was sayin’, “Oh Lordy! Oh Lordy!”

Gran’pa said that his mother said that what caused that—there was a miller there and he’d killed his wife and put her in there, but that’s been many many years ago. I don’t know. It could have been. Gran’pa, I believe, told th’truth, ’cause I never did know him t’tell a wrong. I believe he heard it. I believe there’s things for certain people t’see.

When we lived in that old house right down there, they shore was one down there. Harv Brown owned th’place first, and his wife was afraid t’stay there.

They’uz goin’ t’sell it, so we bought it. And we could hear a horse down there. Harv was afraid of it too.

At night he’d come, and you could be just as quiet as you want to, but when you blowed th’lamp out (back then you didn’t have electricity in this part of th’country) you could hear that horse—and I mean it’d come right up in th’yard just like a feller. You’ve heered a feller ride a horse—what a big racket they make—and it’d stand and stomp till you got up and looked, but when you got up t’look and shined th’light, there wasn’t nothin’ there. You didn’t hear any more that night.

But it’s th’truth if I ever told it—if I’m a’sittin’ in this chair. I’ve heard it.

And Gran’pa said one time that he went t’make music one time fer somebody, and said he broke th’banjer string.

They said, “Well, we’ll have t’quit. We ain’t got another banjer string.”

One of’em said, “John, you run over t’Ken Muse’s.” Said, “He’s got some banjer strings—some extry ones.” Said, “Get one over there.” Said, “It ain’t late and we’ll play some more.”

Said he looked out. Said he wadn’t afraid, but he didn’t like th’idea of goin’ fer he had a big dog that’d bite—a great big ol’dog—and said he said, “It’s pretty dark out there an’ I’m afraid that dog’ll get me.”

“No!” he said. “I’ll make you a board light.” There wadn’t such a thing as a lantern or a light or a flashlight. Said they got him a pine torch and lit it.

He said, “Now if you’ll hurry along,” he said—that’uz just a big ol’pine knot, y’know, and they just keep a’burnin’ and a’goin’—said, “If you won’t stay too long and hurry along, it’ll last you till you get there and back.”

And so he did. He started out with his pine knot, and said he got nearly there and somethin’ just rared up on him and put his hands up on his shoulders and pushed him back’erds and blowed his breath in his face!

Said he reached like that t’push it off and couldn’t feel nothin’, and said that he plodded on pretty fast till he got over there, and he said to him, he said, “Is your dog loose tonight?”

He said, “No. I’ve got him tied up.”

He said, “I thought you kept him tied at night.” He said, “Now you tell me what that was that rared up and like’t’pushed me down out here.” And said. “He’uz ’bout as big as yore dog.” He said it was a big thing, “And it put his front feet right up on my shoulders and like’t’shoved me back’erds!”

“No,” he said. “It wadn’t my dog, John,” he said. “Come here and I’ll show you. I chained him tonight.”

Said he went around t’th’back of his house to his cellar door, and that ol’big dog was tied up there. Said he never did know what that was, but said somethin’ shore pushed him back’erds. And said he had th’light and could have seen if it’d been somethin’, but he didn’t see no dog.

And I know another’n. I know one more I’ll tell’y.

Gran’pa said that one time they moved t’a place, and Mama was their baby. Th’old man that owned th’place lived off in an older house—and his good house, he had it for rent.

Said, “Why do you reckon th’landowner lives in that old house and rents this good one?”

And [Gran’ma] said, “I don’t know.”

“Well,” he said, “I don’t know either, but there’s somethin’ sorta fishy to it. Maybe he gets more pay fer th’better house though.”

Well, Gran’ma done th’milkin’. She went t’milk that evenin’, and when she started milkin’ in th’bucket—you know milk in a tin bucket’ll make a racket—right out from a big rock pile a baby begin t’cry.

Said that Gran’ma just milked on a little while, and said she just took her bucket and went t’th’house and told Gran’pa. She said, “I want you t’come out here and listen.” She said, “When I go t’milkin’, there’s a baby goes t’cryin’ in that rock pile.”

“Why, now,” he said. “There ain’t.”

She said, “Come on out here and hear it!”

She poured her milk out t’where it’d make a racket in th’bucket, and she went back and she started milkin’ and th’baby commenced t’cryin’ again.

They talked t’th’man about it, and he said, “Nah. There wadn’t nothin’ to it.” Said, “People just imagined hearin’ things.”

And Gran’pa, he was a little bit afraid of it. He stayed on a while—just milked and let th’baby cry.

Said that some of th’neighbors around there, they got t’talkin’ to’im. Said they didn’t nobody ever know what become of that man’s wife and baby. Said he had a baby and a wife and they just disappeared and nobody ever knowed where they went to.

And Gran’pa said that he didn’t know, but he sorta thought they might be in a rock pile up there. He said, “When y’go t’milkin’, th’baby goes t’cryin’ out there.”

A bunch gathered up t’gether out there, and they went t’milkin’, and th’baby cried. They moved a big pile’a rocks and dug down there, and he had—he killed his wife and baby and buried’em there and piled rocks on’em.

Gran’pa and Gran’ma, they moved away from there. But that’s why that man couldn’t live in th’house. I reckon they’d come back t’him in th’good house there.

ALEX JUSTICE: One night we just wanted t’camp out, and we saw haints all night. All night. ’Long about ten o’clock I guess it was —th’wheat mill was down there and they’uz a old sawmill down there —somebody come ridin’ a mule up, and somebody come right up t’th’bridge, y’know.

We run out there, and it was gone as quick as we got there.

Then along about four o’clock, there was a yoke of cattle—yoke of steers come down th’road hitched to a sled. They’d get ’bout as close from here t’th’porch there. We saw it all. We’uz just boys. It did scare us. There’uz big old white dogs just a’trottin’ along, and a man—he had on a white shirt and didn’t have no head. Chains a’rattlin’. Then it’ud go away, and then it’ud rise up again. Just a bit down below us—and here it’d come. We’d grab corn stalks and run out there, and there wadn’t nothin’ there.

Then I saw a sled with a load a’wood on it comin’ down th’road, and they wadn’t nothin’ pullin’ it. I could see th’standards on th’sled, I could.

And once my wife was sick—we’d had a dead baby and been t’bury it that day. There’uz snow on th’ground, and somebody come up on th’porch and knocked on th’door.

And old Aunt Katherine Adams was there, and I told some of th’boys that worked with me, I said, “Open th’door.”

And Miss Adams said, “They ain’t nobody there.”

It just walked up and knocked on th’door just as plain as anybody was there, but they wadn’t nobody there.

She told me, she said, “That ain’t th’first time!”

CALVIN TALLEY: Back when I was a young boy—I guess I was about ten year old—I was headed t’church one evenin’, and I rode down th’highway with my brother.

And we got out and I started walkin’ up toward th’church, and all of a sudden a somethin’—there was somethin’ that come around from th’side a’this old building. And it was kindly dressed in white, and I couldn’t hardly make it out. I had always heered that this old building had ghosts, and I couldn’t really understand what it was, but it made me pick up speed!

MYRTLE LAMB: Well, it was up near Sunburst, North Carolina. It was a house nobody wouldn’t live in. Ever’body would get scared, and you would hear all kinds a’rackets.

They said a girl had a baby, and said she didn’t want it so she took it and fed it to th’dogs—or hogs—and when it rained, on a cloudy night, you could hear that baby cry just as plain.

Then in th’house you’d hear all kinds of things—like stockings rubbin’ against th’wall. My mother said ever’ night somethin’ would come and kick th’cover off her. And she would git up and sit up scared t’death, and this other woman got afraid and come and stayed with her and’ud sit and dip her snuff and talk and go on.

MRS. R. L. ELIOTT: Well my mother, y’see, she was raised in a house ’at was haunted. She said ever’ rainy night that there was always noise to be heard.

And her daddy would send’em out, y’know, ’cause a lot of nights would be like hogs under th’floor; and he’d send’em out with lanterns, and they couldn’t see nothin’—but they could hear it. It was just like hogs. And when you’d get around there, why you wouldn’t see nothin’. They’d just hear this noise.

And then maybe a night’r’two later it’d go like horses, y’know—jest different noises all th’time.

And her daddy was just kept a’runnin’ all th’time. They’d go just like a big bunch a’hogs under th’house—rootin’, y’know how they’ll do. I don’t believe you can see a spirit. I think you can just hear’em.

And where anybody is killed, there’s always a noise t’be heard. That’s really true. Now I’ve experienced a lot of that myself, and I know that is true. I’ve been around a lot of these places, y’know, where people has been killed.

I’ve lived up here at th’hotel where Mr. Ramey was killed. One night I was up there. I was out alone—jest me an’m’son—and we heard a bunch a’people comin’ down th’highway a’cryin’. Moon was shinin’ jest as bright as day. And I stood out and listened—kept listenin’—and they kept comin’ closer and closer, an’ come on up t’th’house. Seemed like th’sound jest went around th’house, but I never did see nobody. But it went like a whole bunch a’people.

So I jest went in th’house. I got scared an’ went in th’house, y’know, and locked th’door.

Then one night across th’road from my house it looked like a little calf out on th’side of th’road jest playin’ around, y’know. And they shot at it an’ever’thing, and it jest kept dancin’ right on—playin’ around—and they never could hit it’r’nothin’. Jest a spirit, y’know.

Mr. —- and his wife, they saw it too. We all saw it. Th’moon was shinin’, and hit was jest across th’road there. It was jest playin’ over there jest like a newborn calf. It’uz jest a spirit of some kind.

And my uncle, he said he lived in a house over yonder, an’ after his mother died, one night him and his brother was in th’bed and somethin’ woke him up a’chokin’ him. And he said he tried ever’ way t’get his brother awake and couldn’t get him awake, and he lit th’lamp. And he said when he lit th’lamp, it looked like a big animal that had black hair. And it was a big ol’animal. And he said it made another dive at his throat, y’know, t’choke him again.

He never did get his brother awake, but he follered this thang in th’front room, and he said then that thang went up jest like a ball’a’fire through th’top a’th’house.

You see, that was a spirit. That wasn’t nobody. It went up through th’top a’th’house right there in th’room where his mother’d died.

They’s been a lot a’things seen, and I believe in ghosts.

Now up here right above Rob Williams’ they’s a house there where a old man poisoned his wife. They’s always thangs t’be see’d there. My mother saw a man with no head on there.

We used t’go up there an’ play. They had a downstairs and a upstairs in it. And we—a bunch of us children—was upstairs playin’, and they’uz a baby cried downstairs—cried just like a real baby. So we tore th’top out an’ come out th’top a’that house!

And one night my aunt was comin’ up four house and this big ol’thang caught her in th’road and choked her like a bear. Well, hit’ud sleep on that porch at night. They could hear it lay down on that porch. But they never did know what it was. And her husband’s brother hit it with a axe handle one night, and hit jumped back across th’fence, but they never did see what it was. It was a big thang like a bear.

So I’ve always believed in’em m’self.

And at Miss Maggie’s house they’s always a noise to be heard there at some time. She lived there for years and years, an’ she’d tell us lots a’times about bumblebees in th’winter time. You never hear bumblebees in th’winter time, but she’d hear’em swarmin’ in th’house, y’know.

And my uncle lived in a place where some nights it would go like ever’ dish in th’cupboard would fall out. Said he’d get up and look, and ever’thang was just like it was. Said maybe th’next night it’d go like somebody poured out a bushel a’corn right on th’floor, and it wouldn’t be a thang.

Now up on th’mountain, my grandfather killed a man. They was both drunk, and he killed him up on th’mountain. They got t’fightin’ some way over a still that was cut down on his place, and he cut his head off and laid it up on a stump—cut it plumb off an’ laid it up on a stump—and then he served twenty years in prison.

Well he got rich in prison. He waited on a train robber, an’ he brought back—I don’t know at th’money.

But on that mountain you can pass that stump an’ you can hear things of a night. Anybody on a rainy night, if they want t’hear’em, ought just t’walk down that road an’ they can hear’em.

I took my baby up on th’mountain one time an’ was comin’ back—bringin’ him in a little ol’carriage. Just as I got even with that place I heard a singin’. You never did hear such a racket. An’ bov I drove him off that mountain in a hurry. I brought that carriage down th’road—I got away from that place. I was scared teetotally to death!

MRS. ARDILLA GRANT: I seen’em with m’own eyes. ’Course th’woman that was with me is dead. I couldn’t bring y’t’her, but if she was alive I could. But they’s a house at Hewitts—I guess you’ve heared tell of there in North Carolina—there’s a big house they call th’white house up there, and ever’body that stayed there would hear somethin’, ’r hear somethin’ say somethin’.

Well, one night we went out there on th’end of th’porch, and th’lights was shinin’ out th’windas, y’know; and they’uz a barn out yonder. Great big ol’barn they had.

We’uz out there on th’porch, an’ this ol’lady, she come out from under that barn now. I’m tellin’ y’th’truth exactly th’way we seen it.

Well, I didn’t say a word, nor she didn’t either. We watched her till she just came up close t’us, an’ she had her hands out like that [Mrs. Grant puts her arms out like a sleepwalker in front of her], and she’uz just as quiet an’th’purtiest thing. She was old, y’know, and she had her hands out like that, an’ she came up close. And this woman that was with me, she said, “Lord, child, do you see that?”

And we run back in th’house an’ we told th’men—it was a boardin’ house then—an’ we told th’men what we saw, an’ they got up and went out on th’porch. They thought maybe someone had stopped out at that barn t’camp out’r’somethin’. But they didn’t find nobody. Not a sign of anybody. No tracks nor nothin’. Now that did scare us!

And then down below there—what they call th’Mud Cut—there’s a curve in th’road, and a railroad went aroun’ down there. An’ down below there you could see a man—his legs and a lantern. Y’could see th’lantern an’ his legs; an’ he’d come up on that railroad an’ he’d walk down that railroad t’th’top of th’grade they called it; an’ he’d just get out’a’sight till he’d pop up right in th’same place.

That starts about nine o’clock, and I’ll bet you go right up there tonight at nine o’clock an’ see th’very sight. He’d go along and disappear an’ start right back where he started from. He’d just keep a’goin’, y’know. You could see th’lantern swingin’, and his legs, and right back down th’railroad he’d go.

Now lots’a’people seen that. Now it must a’been in time—some time’r’nother—they’d been somebody murdered there.

[At this point Mr. Grant said that he had heard that a Bill McCathey had killed his brother there by mistake, thinking he was a groundhog.]

Then on up th’road they was a second house that th’railroad men boarded at, y’know. Now I didn’t hear that. This is what they told me; but now they told it, an’ I think it was true: somebody—just went like somebody’d come in an’ thrown down a load a’lumber an’ got t’hammerin’. Just like he was makin’ a coffin.

Well, it just worried somebody that lived there. It was that way continually. An’ it sounded like it was in th’wall, y’know, at times.

An’ he went an’ tore th’ceiling off and he found a little baby skeleton in there!

JUD CARPENTER: One night I was passin’ along, th’moon a’shinin’ pretty bright. It’uz along about ten o’clock at night.

Directly I heard somethin’ come scra-a-a-a-pin’ along behind me. I turned around and looked around. ’Bout that time that thing hit me right in th’bend of th’legs. Felt just like a old dry cow hide.

I danced away, but couldn’t see a thing. I stood around there a while, kept lookin’ around, but never did see nothin’.

Finally I just walked off’n’left it. Never did find out what it was.

And we used t’live in old John Sanders’ house there. They’uz a winder there at th’chimbly end—right next t’th’chimbly. And they’uz somethin’ ever’night’r’two would come there at th’winder and moan an’ groan an’ make funny rackets.

One night it climbed up in th’winder—th’winder was made out a’planks, y’know. He just come up there on that winder an’ scratched and went on an’ kept jumpin’n’scratchin’.

After while, my daddy decided he’d get up and see what it was. When he got out there, it vanished away—couldn’t see nothin’.

They said they’uz a man killed in there—claimed it was hainted. They was right.

And I passed along by th’Methodist church one time. It was ’bout eleven’r’twelve o’clock in th’night, but th’moon’uz shinin’, and th’church doors happened t’be open.

So I heard somethin’ runnin’n’jumpin’ across th’benches in there an’ makin’ th’awfullest racket I ever heered.

I didn’t have no light a’no kind’r’nothin’, but I went on in’ere—went plumb back in th’back a’th’church. That racket disappeared then and I couldn’t see nothin’—couldn’t see a thing in th’world, and th’moon’uz a’shinin’ in at th’doors an’through th’winders too, so I could see pretty well.

So I walked on down th’road a piece, an’ directly I heard a li’l racket behind me. I just turned around and looked. It’uz just like somethin’ a’draggin’ a little old sheep skin’r’somethin’. But I never could see a thing.

HILLARD GREEN: Ghosts are just th’Devil after somebody, and they’re seein’ these things for some lowdown meanness that they’ve done. It’s in their eyes and in their mind is what it is. People will see things where they ain’t nothin’. A ghost is a spirit or something that comes t’somebody that they’ve done evil to—harmed them some way’r’other. Maybe killed somebody.

They’re things that way that can be seen and heard, y’know. Th’Bible speaks about these ghosts and witches and so on. You may not believe in a witch, but they are, for th’Bible tells us.

I’ve heard of’em. I’ve seen’em. I’ve seen people that could witch. They can do just anything they want to.

Now I’ve seen an old woman down on Cowee where I lived, and I know she was a witch. Alan, down there, he wanted t’go and plow somebody’s garden, and his mother said, “No, you’re not a’gonna plow that garden.” Says, “You’re gonna plow mine first or you won’t plow nobody’s.”

And he said, “I’m a’gonna plow over there and then I’ll plow for you.”

She says, “You’ll not do it.”

And he went out there t’get his old steer t’go plowin’. You know, that steer just fell over like he’uz dead nearly. And he lay there three days and he never eat a bite ner nothin’.

Well, Alan took on about his steer, and he tried t’doctor it and ever’thing and finally at last he says, “I’m gonna have t’kill that steer t’get him out a’my way.”

His mammy says, “Oh, you don’t have t’do that. I can go out there and lay my hand on him and that steer’ll get up if you’ll go out there and plow my garden.”

He says, “Well, Ma, I’ll plow it then.”

She just walked out there t’that steer and laid her hand on it, and that steer jumped up just th’same as there wasn’t a thing in God’s world th’matter with it.

I’ve seen a lot of things that she done, and I know she could do anything in th’world she wanted to that way t’destroy you. That was forty-seven years ago when that happened. I’uz livin’ right close t’them.

I seen her get mad one time and witch a baby, by gosh, till it died ’cause she got mad at th’parents. There’s somethin’ to it. You don’t know when it comes t’their power.

Be like old Mrs.——-over here was. Lived right over here across th’ridge over here. She got her a book and was goin’t’learn how t’witch.

And somebody come t’her, y’know. Told her where t’go to out there on th’ridge and set down on that log and then they’d come and learn her.

Well, when they come to her, they said, “Now you put one hand under your foot and one on top of your head and say, ‘All th’rest belongs t’th’Devil.’ ”

She said that she couldn’t do that at all. They’uz somebody standin’ there but she. didn’t know who it was. And she said, “All that belongs t’God-a’-mighty.” And that person was gone and she didn’t see nobody and didn’t know nothin’. She just got up and went t’th’house and throwed her book away.

A spirit can appear to you any time that way if you’ll serve th’Devil.

3

In addition to the retellings of personal or interfamily experiences, we were also told a number of pure ghost tales—tales that have been told and retold throughout the Appalachians for years. They are a part of a rich oral mountain tradition. And they’re also among the wildest stories we’ve ever heard.

ETHEL CORN: There’s an old tale told; I don’t know who it was, but said there was this hitchhiker. He wanted a place to stay all night, and they told him that he could stay in that house, but it was hainted. He said he didn’t believe in’em. There weren’t no such thing an’ he’d stay in there.

Later on he heard cats around, an’ this cat with no head jumps up on th’bed. That feller, he jumped out of th’bed an’ he started t’run-nin’ t’get away from it.

Said he run down th’road till he give out—till he thought he was fer enough away that there wouldn’t be nothin’ around. He’d sit down t’rest, and said that directly somethin’ said, “We’ve had a hell of a race, ain’t we?”

He turned around an’ there set th’no-headed cat by him!

GRADY WALDROOP: Man said, “I got a house over there on th’edge a’town. You can stay in there all night—all winter if y’want to. Won’t cost a dime. There’s plenty a’wood, books an’ever’thing in there.” Says, “I’ll tell y’th’reason it’s thataway.” Says, “Ever’body that’s ever stayed there says it’s hainted.” Says, “There’s a ghost comes in there an’ they all afraid a’it.”

“Aw,” he says. “I don’t care nothin’ about that. I won’t be afraid-’r’nothin’. I’ll just go over there. May stay a day’r’two.”

He went over an’ fixed him some coffee an’ lunch an’ ate it. Got a book and’uz settin’ readin’ when a big ol’cat come down an’ went up an’ wallered in th’fire an’ says, “Don’t know what t’do about attackin’ y’now.” Said, “I reckon I’ll wait till Martin come.”

Said he didn’t like that much. Said he got him another book.

Directly here come another’n down th’steps. Big ol’angoran cat. Said he got under th’forestick an’ rambled around an’ knocked fire all over th’place, an’ he kicked th’fire back’n said, “Y’wanna commence on’im now or wait till Martin gets here?”

“Well,” [the man] says, “I don’t know when Martin’ll get here, but when he comes, you tell him I’ve been here and gone!”

JIM EDMONDS: There was a man one time—had a lot of money, all silver. Had no greenbacks then. Had about half a bushel of silver—sold his place out, y’know, an’ was goin’ t’go out west—out of th’country. So he was gettin’ ever’thing ready. Had his money he got from th’place, y’know.

So he got this feller t’come and give him a shave as he was gettin’ all fixed up and ready t’go. Well, th’feller got him half shaved, an’ then he took th’razor and cut his throat an’ killed’im. But th’feller couldn’t find th’money ’cause th’guy had it buried.

Well, they find this guy dead. They didn’t know what happened ner nothin’. Somebody killed’im, but they didn’t know who did.

When people way back then would start t’go from one country t’another an’ they didn’t have a place t’stay, they would just go on an’ find a empty house. Some folks came drivin’ by one day lookin’ fer a place and asked a feller about it. He said, “I got a place down there. Can’t nobody live down there. Tell what I’ll do. If you live in that house fer twelve months, I’ll give it t’you. Can’t nobody live down there. Don’t know whether you can stand it’r’not. You can move in th’house if y’want and live there.”

They just had one child, y’know. Th’little feller, they just laid’im on th’bed. Th’old man, he was out workin’ around gettin’ wood and fixin’ up—goin’ t’stay all night. Th’woman, she was a’fixin’ supper, and here come a man runnin’ in with his head half cut off and a razor in his hand startin’ like he was a’goin’ t’th’bedroom.

That woman was scared t’death and said, “Lord have mercy; don’t kill my baby!”

He just stopped right quick and said, “Fine thing you spoke t’me. Tell you what I’ve come fer. I want you t’do somethin’. You do what I tell you.”

He told her th’man’s name that cut his head off. Said, “I was fixin’ t’leave here and he cut my head off t’get th’money. Tell what I want you t’do. You go and swear out a warrant for that man and get him to come to court for a trial. You don’t need no witnesses. Don’t need no witnesses. You just have him come to court. You’ll have a witness. And I’ll tell you what I’m goin’ t’do. You’ll have some money. You come and foller me.”

He just went down a little ways t’where a big rock was a’layin’ there. Said to move that rock, but th’woman said she couldn’t. But he said, “Yes you can.”

So she reached down and that rock just turned over real easy and there was all that money down there where he had dug th’hole. He said, “Now you get all that. That’s yours. You do what I tell you—you have a trial and have him come t’court, and when you get ready t’have a witness, you’ll have a witness.”

She went ahead and had that man arrested—got that man and told him what he was guilty of. People, didn’t understand at all. Th’judge asked him what he was charged with. “Murder,” he replied.

Th’judge then asked him if he was guilty or not guilty. About that time, here come that feller walkin’ in th’courtroom with th’razor in his hand and his face half shaved and his head half cut off.

When that man saw him, he just tumbled over dead!

MRS. MARY CARPENTER: There’uz a man one time—him and his wife was a’travelin’ along, and he said they went t’a house and they went in. Said that it was a’rainin’ and they was a’goin’ t’stay all night.

And he told her t’stay in th’house—light a lamp and stay—and he’d go t’th’field and see this man and see if he cares if they stay all night in his house.

Said she went in and scrambled around and found some matches and lit th’lamp. Th’house had furniture in it. Said there was a Bible layin’ there on th’table and she just opened it up and set there by th’lamp and was a’readin’. She just kept a’settin’ there waitin’ fer him t’come back. Said it was rainin’ harder, y’know. She thought that when it slacks he’ll come back.

Her husband went over in th’field and they told him th’house was hainted and that you couldn’t stay there.

She just kept a’settin’ there, and directly a great big drop a’blood just hit th’Bible there and just splattered out on it.

She looked up and didn’t see anything. She just read on. Pushed her book up a little and read down below it.

Another drop dropped on it.

Said she just set there and read on till th’third drop dropped. When th’third drop dropped down, said she heard somethin’ a’comin’ down th’stairs and she just looked around. This haint, he just set there and said, “Well, you’ve been th’only person that’s ever stayed here when I come back.”

“Well,” she asked him—however it was to ask him—“Well, what do you want? Why did you come back?”

Said he was killed fer his money there but they didn’t get it. He said that they’uz a fireplace in th’kitchen, and they killed him and buried him under th’hearth rock. He said his bones was under there and asked if she’d take them up and get a coffin and put them in it and bury’em in th’graveyard. Told her where t’bury’em.

Then he said, “You come back and look out there at th’gate under th’tree and dig down so fer”—I forget just how fer. Said his money’uz buried there and he wanted her to have it.

Th’next morning th’old man come back at daylight and asked her if she was ready t’go. He wouldn’t come in.

She said no, she wasn’t ready t’go, and wanted to know why he didn’t come back. He told her th’house was hainted.

She said, “You just go along if you want to. I’ve got a job to do.” And she just dug that ol’hearth rock up and got him up and took him and buried him and dug th’money up, and it was shore’nough money. Said he had a lota’money buried out there.

But I don’t know if I could have read with that blood a’droppin’ or not. I’d be afraid somethin’ was upstairs hurt and would’ve come a’tumblin’ down!

I don’t know who told me this’n. Somebody said they was a preacher and he had a boy that was awful mean, and all he done was hunt—fox hunt, y’know. Ever’ evenin’ said he’d gather up his ol’pots-’n’pans and his dogs and his gun and go out campin’.

And said his daddy thought if he could just scare him, maybe he wouldn’t go. So he went up to th’church and left his Bible up there. He’d hired a man t’scare him, y’know, up there at th’church.

Th’boy was a’gettin’ his food and stuff up ready t’go, and he said t’him, said, “Son, you goin’ a’huntin’ tonight?”

And he said, “Yeah, I thought I would.”

And he said, “I wonder if you could run up to th’church and get me my Bible before you go.”

“Oh, yeah,” he said. “I got plenty a’time.”

So th’boy, he went runnin’ up there to git th’Bible, opened up th’church door and walked in. Said he got good’n’started, and said there’uz somebody in behind th’pianer said t’him, “What are y’after?”

And he said, “I come after my pa’s Bible.”

Said he said, “You’re not a’gonna git it.”

And he said, “I’ll git it too.”

And he said, “You ain’t a’gonna git it.”

Said th’boy just kept a’walkin’ and went on up through there. Said he was just a’cussin’ as he went, th’boy was.

And he come on back, and th’preacher was sort’a surprised that he got th’Bible. He said, “Well, did you git it?”

And th’boy said, “Yes. I got it.” And cussed again and said, “I had a time a’gettin’ it. They’uz somethin’ up there said I wadn’t gonna git it, but I showed’em anyhow. I got it.”

So he laid th’Bible down and got his dog and went on and went to a old house. He was a’makin’ his coffee and fryin’ his meat, and said his coffee boiled and he set it over in th’corner. Said th’stairway come down in th’corner there, and said they’uz a box like a big size tool box come a’slidin’ down’n slid right up on th’hearth rock right by where he was.

He looked around and said, “That’s a mighty nice thing t’set my coffee pot on.” Said he just picked it up and set it down on it.

Was fryin’ his meat and th’lid began t’come up. He said, “Wait a minute! Hold on! You’re gonna spill my coffee!”

He set his coffee pot down and said somethin’ come out. It was somebody with a white shirt and no head on, and said he told th’boy about his money. Asked if he had a sister and he said he did.

Th’haint said, “I want you t’divide it with her. If you’ll give her half of it, you’ll never hear from me again; but if you don’t divide it with her equal, I’ll be back every time when you don’t want me t’be.”

So he went and dug th’money up and went on back and sent half of it to his sister, wherever she was.

Now I believe I’d run when somethin’ began t’spill my coffee!

MINYARD CONNER: There was a boy that went possum huntin’ one night. Took his dog and his lantern, and he’uz a’goin’ along up a holler, and they’uz a old tiny log house up there. It was about fell down, y’know.

He seen a little dim light in it, and he just put his light out, y’know. And he just kept easin’ up and easin’ up, and atter while he peeped through a crack, y’know.

He looked in there and he seen five’r’six oh awful pretty women in there just a’dancin’ around, y’know. Around’n’around. Just watch-in’em.

Atter while one come up t’th’chimney, reached down and got a’hold a’th’hearth rock and turned it up sideways. She rubbed her hand down on th’back side, y’know, and rubbed it on her chest and said, “Up and out and over all; up and out and over all.” He said she was gone like a flash then.

Said th’last one done that. Said when she done that, she kicked th’rock back.

Well, he got a’hold a’that rock and he begin t’hive and hive, and directly he pulled it up—yanked it up sideways. Put his hand over there where they had been a’feelin’—where they had been rubbin’ their hand. It felt sort’a greasy to him.

He just rubbed th’rock, y’know, and he said, “Up and out and through all. Up and out and out through all.” They had said, “Over all,” y’know.

And he give th’rock a kick and he just out th’window he went just like a flash, y’know. Out through th’hills and briers and bushes, y’know, just a’knockin’ and bangin’ and slammin’ and cussin’. And he kept goin’ and goin’ and he went across a big wide river and ended up where they was havin’ a dance. Big fine place, y’know. Said they was big white horses all around there.

And said he went in and he danced with’em. Said one of’em come t’him and said t’him, “Now don’t say th’Lord’s name at all!” He give hisself t’th’Devil. Said they went up ready t’leave then.

Said they went back out and they all got on their horses and here they went. Said they pointed to a bull calf and he began t’stamp. Said, “There is your horse.”

So he jumps on that little devil. Said here they went just a’keepin’ up with them big white horses, just a-lip-a-tee-lip tee-lip tee-lip—goin’ right on.

Said directly they come to a great big creek. Said they all jumped it and that bull calf just laid right in there and went across with’im.

Said directly they jumped a big wide river. Said he said, “God Almighty what a jump!” and he was in th’dark!

4

Logically enough, the kinds of phenomena described here have given rise to a number of superstitions, many of which are still firmly held as fact by individuals here. Ed Watkins, for example, claims that if you rebuild or repair a part of your house with new lumber, any ghosts that are there will leave. Others follow.

JIM EDMONDS: A witch will come t’borry somethin’. If they don’t get nothin’, then they can’t do nothin’ to you.

I heard about a man—a witch said he’d make a witch out a’him if he followed him. They come t’this door and th’witch said, “Hi-ho, hi-ho! In th’keyhole I go.” He went on in and got all he wanted.

Th’other feller said th’same thing and in he went and got all he wanted—ate all he wanted.

Th’old witch came and said, “Hi-ho, hi-ho! Out th’keyhole I go,” and went on out.

Th’old man came and thought he’d do what th’other did and said, “Hi-ho, hi-ho! Up th’high hole I go,” and fell t’th’floor!

You just had t’pay no ’tention t’witches. They can put a spell on you, but they can’t turn you into a witch if you pay them no mind.

ETHEL CORN: I was livin’ in Charlotte—we lived off in th’back-woods. There one night about eleven o’clock we looked up an’thought th’house was on fire.

I got up and looked out, and back in th’east it looked like th’sun a’drawin’ water—but it looked like streams a’blood a’comin’ down. And it went straight a’towards th’north and it lit up till you could’a’-picked up a pin in th’house. I guess it’uz ten’r’fifteen minutes goin’ on.

And it looked like that was blood comin’ plumb down t’th’ground. They was a lot a’people see’d it, but nobody knowed what it was. It lit up th’whole house, and it like t’scared th’young’uns all to death.

I wasn’t scared because I believed it was representin’ a fulfillin’ of places in th’Bible. An’ I got th’Bible and got t’readin’ in Revelations where it speaks of all these things and wonders that we’ll see—it was somethin’ that God had sent. It wadn’t intended fer us t’know just what it was all about.

ILLUSTRATION 3 Ethel Corn

And before Uncle Jake Collins died, he see’d a light, and it looked like a torch. It was just two’r’three days before he died—er nights rather. They was a trail come from th’house down through our swamp, and he watched hit, an’ hit come on down right at th’end of th’swamp and went up by his bee gums and come down nearly t’th’kitchen door, an’ hit went out.

It was just two’r’three days after that that he fell dead, and we always thought it was a “talkin’ ” of his death, because “talkin’s” will be of things t’happen like that.

Looked like somebody just a’carryin’ a pine torch lit in their hand, an’ it come down fright at th’kitchen door and it just vanished.

And another “talkin’ ”—we had been workin’ in th’fields up behind th’old Union Chapel Church, and hit went like benches and everythin’ else turnin’ over in that church. And I thought there was somebody in there who’d broke in, and I went and th’doors was still locked; and I looked in th’winders and we never could see nothin’. There was no benches ner nothin’ disturbed.

And I went on home. That evenin’ late they come and told me Gertrude Norton was dead. They’uz goin’ up there t’ring th’bell.

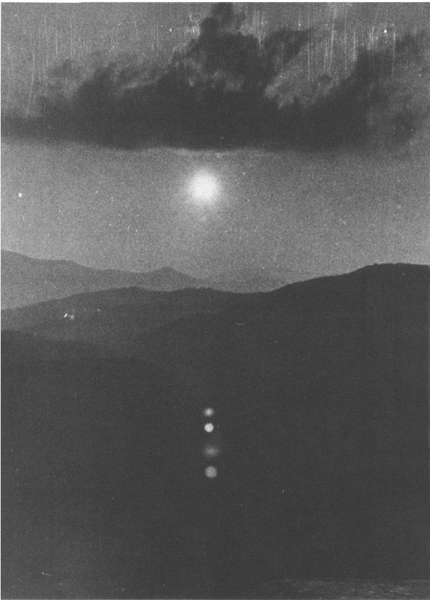

ILLUSTRATION 4

ILLUSTRATION 5

AUNT NORA GARLAND: My mother and Aunt Jane—they was young girls then—they were a’goin’ some’ere t’spend th’night with somebody, and they were goin’ together, y’know. They was t’meet in a certain place.

Well, she waited and waited and waited there in that place, and she never did come. And she started up th’road and she looked back and seen her a’comin just as plain as she’d ever see’d anybody in her life.

But it wasn’t her. She was dead. That was th’reason she wasn’t comin’. She was dead.

She said she’d see’d her plainer than anybody in this world, and stopped and waited and thought that she was comin’ on, but she never did come—some kind of a vision.

And they say t’never look back, y’know. They say t’never look back ’cause if y’do, you’ll be th’next t’die.

MYRTLE LAMB: I always possum hunted. We would always go on a rainy night in these old fields. That is th’place t’go. They would always go up in a old tree that is growed where nobody lives. Go on a dark, drizzly night. I always had th’best luck with’em.

I was comin’ back, and m’shoes was hurtin’ m’feet. I set down t’pull m’shoes off. I just felt like somebody was right behind me. I looked back, and he was just a little ways from me. He said he wanted t’pray fer me.

I said if he wanted t’pray fer me t’stay right there. I wadn’t a’goin’ with’im.

Then a night’r’two after that, he claimed he’d been to Franklin. I believe he was tryin’ t’come up Middle Creek and said he got lost. Then he come—said he wanted a lantern.

I didn’t feel like he was gone, and I went upstairs and looked out th’window and he’uz standin’—his light was shinin’ out from under th’porch.

My mother and my brother went out and he run through th’corn fields.

Later it was like somethin’ up in th’upstairs jumpin’ up and down. I heard it twice. People said that was a warnin’, and th’next day, my mother got bad off with pneumonia.

MRS. MARY CARPENTER: I reckon I must be superstitious’r’-somethin’, whatever y’call it. If a rooster crows of a night, th’older people said somebody’d be sick. Or if somebody went t’bed a’laughin’ and a’cuttin’ up and a’havin’ fun, somebody’d be sick in th’family, or your neighbor’d be sick’r’some one of’em dead.

One night —- and —- went t’bed a’laughin’ and a’cuttin’ up, and their mama said, “Cut that out in there.” Said, “Somebody’ll be sick in th’mornin’.”

And said next mornin’ ’fore they got up that somebody was knockin’ on their door. Their closest door neighbor, one of’em was dead.

And you heard about my boy fallin’ on his shotgun and gettin’ shot? Well, about two’r’three nights before—now I don’t know if that had anything to do with it or not—but that rooster crowed at midnight and I thought it was time t’get up. They wake me up when they crow, so I jumped up—thought it was time fer’im t’get up and go t’school.

And I got up and it was just midnight. And John, he told me that chickens crowed anyhow at midnight, and I said, “Well, maybe they do.”

I didn’t think too much about it, but it wadn’t too long till I was back asleep and they waked me up a’crowin’ again. Well, I bounced out t’see if it was time t’get up and go again, and it was between two and three o’clock. And I knowed then. I thinks, “Well, somethin’ must be goin’ t’happen t’us.”

And two’r’three days after that, LeRoy, he started t’huntin’. And there was snow on th’ground, and ice, and he stepped on a log with ice on th’log and his foot slid and he fell off backards off th’log and shot his foot in two.

I don’t know. I guess there’s nothin’ to it, but I couldn’t help think it was because that rooster crowed. I killed th’rooster. Yeah, I killed that rooster before he ever got out of Greenville Hospital. Took him off out yonder and dug a hole and buried him.

ILLUSTRATION 6

HAINT TALES AND OTHER SCARY STORIES

Storytelling is not an uncommon thing around here. It’s a tradition in my family that’s been passed down from generation to generation.

When I was a small child, my grandmother, Ruth Holcomb, would always tell me stories—day or night, it didn’t matter to her. Whenever I wanted to hear them, she’d sit down with me and tell panther stories or mad dog tales. Those were my favorites and she knew lots of them because she grew up seeing mad dogs in the neighborhood and hearing about panthers (pronounced “painters” by some people around here).

We always sat in the living room when she went to storytelling. She’d tell me story after story and have me so scared there was no way I’d even go into the next room by myself. Somebody would have to go with me.

I was always told if I saw a dog coming up the road, when I was waiting on the school bus of a morning, and it was foaming at the mouth, I was to either lie down in a ditch or stand real still and try not to breathe, so it would pass on by without biting me. I went to wait on the bus one morning and I practiced how to hold my breath and stand completely still. I think it’s silly now that I look back on it, but I sure believed it then.

When I began editing these stories, I was at home lying in front of our heater on my stomach. Nobody was around me. Mom was taking a nap and Dad and my little brother were away. The television was off and it was real quiet. The house was popping—you know how a house does when it cools. And it was pitch dark outside. I got so interested in these stories that they were giving me a creepy feeling all over, and I finally decided I’d better put them away till the next day.

Kim Hamilton, Rosanne Chastain, and I collected most of them over the summer. Others had been told to Foxfire students over the years but have not been published previously. Tales about panthers and mad animals get inserted into someone’s conversation occasionally and don’t seem suitable as you’re putting together an article that deals specifically with some other subject. So this was an opportune time to pass along stories we’ve had tucked away in the files for a long time.

Every person that told us haint tales or scary stories was quite happy to share them. Each of them had his or her own unique and fascinating way of telling them. Lots of the stories have come from their own personal experiences and from what their parents and grandparents had passed on to them.

I still love for my grandmother to sit down and tell me these stories. I get terrifying feelings of panthers tearing through my skin or mad dogs snapping up at me, but I really know I’m quite safe with Granny.

Put yourself back in time and let your imagination roam as you enjoy these stories. Can you see a panther getting after you or a mad dog biting at you? What would you do?

DANA HOLCOMB

PANTHER TALES