B is for Bauhaus, Y is for YouTube: Designing the Modern World from A to Z (2015)

What distinguished Charles Jencks’s best-known book, The Language of Post-Modern Architecture, first published in 1977, was the violence of its traffic-stopping first sentence. ‘Modern Architecture died in St Louis, Missouri, on July 15, 1972, at 3.32 p.m. (or thereabouts) when the infamous Pruitt-Igoe scheme, or rather several of its slab blocks, were given the final coup de grâce by dynamite.’ This was not the first attempt to abolish modernism and all its works in the name of what has come to be called postmodernism. A decade earlier, the architects Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown (who later went on to design Britain’s most visible piece of postmodernism, the National Gallery extension), had written Complexity and Contradiction, a book dedicated to the proposition that less, rather than being more, as Mies van der Rohe used to suggest, was in fact a bore. They took, gently enough, to decorating their buildings in pastels and floral prints, incorporating fragments of historical detail and quotations from past architectural styles, and toured Las Vegas to learn from Ceasar’s Palace.

Little more than half a lifetime after modernism had consolidated itself as the style that was going to end all styles, Jencks went a lot further than Venturi and Scott Brown and declared modern architecture to be dead on arrival. It was a pronouncement that said as much about the ambition of the man who made it as it does about modernity.

Jencks claimed that the fact that ‘many so-called modern architects still go around practising a trade as if it were alive can be taken as one of the great curiosities of our age, like the monarchy giving life-prolonging drugs to the Royal Company of Archers.’ Who knows what even more excitable a conclusion he would have come to if he could have known that another huge complex, also designed by the architect of the Pruitt-Igoe, was one day going to suffer a far more tragic end. Minoru Yamasaki was responsible for the World Trade Center in New York. Jencks’s glee over the destruction of Pruitt-Igoe, which was, as he put it, ‘finally put out of its misery, Boom Boom Boom’, certainly has a more troubling resonance now than it did when he wrote the words.

What did it matter, as Jencks later admitted, that he had made up the killer detail that pinned the time of the blast down to the precise minute? According to William Ramroth’s account, Planning for Disaster, Jencks got both the date and the time wrong. Or even that Yamasaki, a Japanese American with a taste for florid appliqué Gothic ornament, was not, strictly speaking, a modernist at all. Or that, contrary to the newspaper version, Pruitt-Igoe had never won an architectural award and that, as revisionist historians led by Katharine Bristol suggest, the decline of the project had more to do with the absence of fathers living with their families on the estate than with the modern movement. Never mind any of the nuances, the dynamiting was an unforgettable image that allowed Jencks to make his authentically breathtaking declaration that was intended to mark the end of something big. Jencks was just as interested in trying to start something he sincerely hoped could turn out to be equally big, something that he called postmodernism, and which he presented as his own invention. In Jencks’s eyes, if not in everybody’s, postmodernism meant design with the wit, the emotions and the history that modernism had rejected, put back into the mix. It was permissive rather than prescriptive, ambiguous rather than clear, catholic in its tastes more than it was Calvinist.

But for those who did not see it in the same way as Jencks, postmodernism was an even bleaker choice than modernism. It was not so much a break with the recent past as it was a further development of it. Postmodernism was modernism plus French literary theory.

What Jencks did not do with any conviction was to define exactly what constituted modernism, or, for that matter, postmodernism. But those omissions did nothing to lessen the impact of his book. Was postmodernism in design questioning capitalism? Yes, said many of its early advocates; but it quickly became synonymous with overconsumption, with Michael Graves’s bombastic corporate architecture, and with red plastic birds attached to the spout of an Alessi kettle.

So confidently and so matter-of-factly to write off architectural modernism as dead, and then to dance without a hint of regret on its grave, suggested an overwhelming finality. This was not like saying that art deco was old-fashioned, or to claim that pink was the new black. Nobody ever saw the jazz age as anything more than an amusing, but passing, fashion. Nobody mourned the end of art nouveau. But to be a modernist was not merely about making things look fashionably up to date. It was to have a point of view about everything from music to psychoanalysis. It was to take a moral stand about the ‘honest’ use of materials, and to believe in the designer’s duty to build a better world with the aid of flat roofs and an absence of capital letters. Certainly no other adjective was applied with such promiscuous abandon to almost everything, or is still able to evoke a very particular way of seeing the world. Modern art, modern architecture, modern jazz, modern movement, modern life, these are signals to suggest the way that the world was meant to be. ‘Modernist’ isn’t the same as ‘modernism’. One can be equated with the contemporary, the other has come to mean a very particular creative approach, one that has alternately fascinated and repelled us.

Since before the First World War, ‘modern’, a word carved in steel and concrete, with such apparently unarguable clarity in an impeccably severe sans serif font, had a power like no other adjective used to denote a cultural movement. Setting aside the rhetoric of the demands of the spirit of the age, about new ways of seeing space, ‘modern’ meant boiling down every complex shape into its constituent forms: cubes, cones and spheres. It involved using non-traditional materials and techniques. But to mean anything of substance, modernity demanded putting those tactics to work to create a new way of life. Modernity was about a new way of seeing the world, not just a new way of seeing space.

Jencks’s book didn’t bury modernism all by itself. As a movement, it has had all kinds of challenges, from its friends as well as its declared foes. You might equally well argue that ‘modern’ died on the day in 1929 that Alfred Barr and the Rockefeller family captured it through the skilful deployment of their all-conquering money trap and stored it safely away in their vault, New York’s Museum of Modern Art, where it could do no more damage. By doing so, they had turned a turbulent social and cultural force into an aesthetic category.

If modernism was dead after it had done so much to shape every detail of our everyday lives for so long, from the cars that we drove to the art in the galleries and museums, and the typography of our postage stamps to the division of our cities into functional zones, which separated houses from shops and offices from factories and transport from schools, what is left to provide us with a compass for understanding the world?

After modernism had been declared dead, architects began to build apartment complexes that looked like Roman amphitheatres and aqueducts. They decorated their façades with fragments of classical columns, and used a lot more colour. It wasn’t only architecture that was transformed, product design and typography and even car design followed a similar course.

Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown’s range of furniture for Knoll, designed in 1984, took the form of some highly selective quotations of decorative styles, including Chippendale, Sheraton, Empire and Art Deco, and applied them to moulded plywood. That Knoll was a design-conscious company which had established its reputation by manufacturing Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona chair made the sting of their apostasy all the stronger. Their detractors saw this as little more than a cartoon, a travesty of the authentic original. For Robert Venturi, less might have been a bore. But Knoll kept Venturi and Scott Brown’s designs in production for no more than four years, suggesting that people could tire of excess as quickly as they did of restraint.

With rather more originality, Daniel Weil deconstructed the language of consumer electronics. He made a radio that dispensed with a conventional rigid case in favour of a see-through plastic bag, inside which the circuit boards were decorated and clearly visible alongside random fragments of cloth.

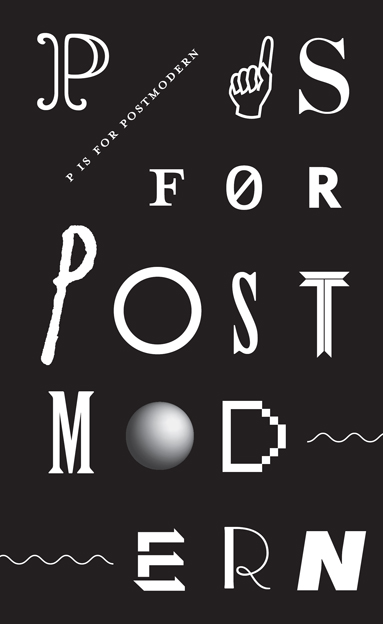

For a brief moment, the postmodern idea spread everywhere, matching the explosive eruption of art nouveau at the turn of the twentieth century. Typography became militantly illegible. Cars turned playful. This eruption of disorder served to enrage the more inflexible of architects and designers. Harry Seidler, once a student of Walter Gropius at Harvard, who later moved to Sydney to become one of the founding fathers of Australian modernism, ill-advisedly suggested in his old age that postmodernism was the architectural equivalent of AIDS.

Paul Rand, who played a part in American graphic design very close to Seidler’s in shaping Australian architecture, producing corporate identities for Steve Jobs as well as for IBM and Enron, was dismayed by what he called a ‘collage of confusion and chaos, swaying between high tech and low art, and wrapped in a cloak of arrogance’. He was, of course, talking about postmodernism, and what he called its

squiggles, pixels, doodles, dingbats, ziggurats; boudoir colors: turquoise, peach, pea green, and lavender; corny woodcuts on moody browns and russets; Art Deco rip-offs, high gloss finishes, sleazy textures; tiny color photos surrounded by acres of white space; indecipherable, zany typography with miles of leading; text in all caps (despite indisputable proof that lowercase letters are more readable); omnipresent, decorative letter spaced caps; visually annotated typography and revivalist caps and small caps; pseudo-Dada and Futurist collages; and whatever ‘special effects’ a computer makes possible. These inspirational decorations are, apparently, convenient stand-ins for real ideas and genuine skills.

Both Seidler and Rand were responding to a sense that they, and the ideas they believed in, were under threat. They saw themselves as stranded by a retreating historical tide, and believed that their successors were doing their best to commit patricide on them. The Harvard of the early 1960s in which Jencks had studied was still a place in which Gropius’s influence was pervasive. A decade later the first of the postmodernists were determined to take their revenge.

For a moment in the 1970s and the 1980s, ‘modern’ really did seem to be dead. Architects went through a kind of collective nervous breakdown. Under the lash of the Prince of Wales, who (with singular lack of taste and judgement) famously suggested that, ‘say what you like about the Luftwaffe, they did less damage to London than Britain’s modern architects’, they sheltered under the alibi of a vernacular style, or even a kind of classicism. The ambition to build a sunlit new world that had driven modernism for so long had apparently evaporated.

And then postmodernism withered and died away so quickly that it looked as if Rand’s and Seidler’s scorn might have been right all along. Michael Graves, perhaps the most celebrated of the architectural postmodernists, saw his reputation go through a particularly sharp decline. What had seemed witty and provocative quickly became frivolous, excessive and indulgent. In the 1980s, Jencks, in his film Kings of Infinite Space, described Graves as the most significant American architect since Frank Lloyd Wright. Then, after the world took in the spectacle of Graves’s vast hotel in Florida for Disney, topped by gigantic representations of swans, it was almost impossible to find anybody prepared to admit that they had ever been a postmodernist. After that, hiring Graves to build a museum or a company HQ became an admission of being terminally out of touch rather than daringly innovative.

By the time the Victoria and Albert Museum got around to its retrospective on postmodernism, forty years later, it was a moment in design history that seemed as though it had well and truly passed. The virus had been made safe, fit to reappear in its defanged, deactivated form.

If investigating the moment that modernism did or did not die is problematic, working out its origins is also not without its difficulties. Putting modernity down to Walter Gropius’s Bauhaus manifesto from 1919, with its expressionist woodcut cover and its William Morris-influenced ideas about the unity of all the arts, design and architecture, or even to Adolf Loos’s writings in the Vienna newspapers in the years after 1900, is to miss the impact of the industrialization of the previous 200 years, of the enlightenment and the invention of the scientific method. Modernism was used in a derogatory sense as early as 1737, when Jonathan Swift branded those who abused contemporary language as ‘modernists’.

The critic and architectural historian Joseph Rykwert takes an imaginative leap, claiming, convincingly, that ‘modern’, as it relates to design, is a concept that begins at least 250 years ago, with the separation of architecture from what were once called the other arts. It is now, he says, a divorce; one which he clearly regrets in that he finds most of what we build now either too banal to discuss or else somehow too empty to notice. But from his acid view of the direction that both art and architecture have taken, you could be forgiven for assuming that he does not believe things would have been much better if the two parties had decided to stay together for the sake of the children.

Rykwert looks back to the days before modernity, whose origins he puts back to a point shortly before the Adam Brothers got going with their eighteenth-century drawing rooms ornamented with plaster swags extruded on an industrial scale, and their mass-produced door furniture. There was, he suggests, a shared public realm then, as well as a shared public culture. As Rykwert sees it, this was a time when artists would have never dreamed of canning their own faeces, an act which seems to have earned Piero Manzoni the unyielding contempt of Rykwert. It was also a time when an architect could have expected to have been consulted about the placing of 500 feet of rusting steel in front of one of his buildings in the name of sculpture. It was a time before the world of advertising and graffiti transformed our cities by hollowing them out of any more complex layers of meaning. This last sounds like a misplaced confidence in the authenticity of pre-industrial cities.

If modernity had its origins in the Enlightenment, modernism, with which it should not be confused, began to be formulated around the time of the First World War, and its first and most energetic period came to a close twenty years later, though it was to spawn a second generation of modernists in the 1960s. It was shaped by such developments in painting as the geometry of purism. Le Corbusier’s architecture was a response to the spatial explorations of cubism. It was influenced by cultural innovation in many different fields, from James Joyce’s literary experiments to Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalysis.

Early histories of modernism concentrated on Western Europe. But it went much further than that. Its roots were not just in Paris, where Le Corbusier settled, but also in Weimar, where Walter Gropius opened the Bauhaus, the art school that established the language of modern design, and in the Vienna of Adolf Loos. It had an early impact in Glasgow and Prague, Budapest and Helsinki. For a short period between the two wars, Czechoslovakia saw itself as a proudly and self-consciously modern state. After the expulsion of the Hapsburgs, the Czech kings were reburied in Prague’s Saint Vitus Cathedral in a new, and radically untraditional, catafalque. The Bata family commissioned an entire new industrial city, in which Tomáš Bata’s own office was a glass-walled elevator that allowed him to move from department to department.

What distinguished modernism was its vociferous rejection of history, tradition and precedent. Gropius, Le Corbusier and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, the godfathers of the movement, were driven by the urge to design every chair and teacup as if no such thing had ever been done before. They had a messianic obsession with the idea of the machine, coupled with a tendency to equate design with morality. They believed that decoration was reprehensible because it hid the unadorned truth they professed to find in modern materials. Modernists used the house as a battering ram in their onslaught on conventional ideas, if not necessarily on how domestic life should be lived, then at least on how it should look. White walls, bare ceilings, glass walls and chromed steel fixtures were in themselves an emblem of newness. There was a view that objects should at least be made to look as if they were machines, or made by machines, even if they were actually the product of laborious handcraft. The hard-line technocrat Buckminster Fuller was scornful of the kind of functionalism that confined itself to how the kitchen taps looked, but showed not the slightest interest in the plumbing and water mains on which they depend.

Modernist designers were narcissistic enough to redesign themselves in the spirit of their obsessions. They were forever coming up with simplified, ‘rational’ new garments, or adopting those thick black-rimmed spectacles in perfect circles, to blink photogenically at the camera. Vladimir Tatlin’s 1923 design for standard ‘worker’s’ clothing, with detachable flannelette lining and wide sleeves ‘to prevent the accumulation of sweat’, was typical. The uniform is completed by a flat cap and boots. Alexander Rodchenko was equally interested in radical ‘constructivist’ clothing. This was the kind of thing that drew satire, as well as persecution, from the Nazis.

Modernism has defined our tastes to a remarkable degree. Without it, there would be no built-in kitchens, and no loft living. The schools and hospitals of the rich world would look very different. Without modernism, Britain’s contemporary domestic landscape would be an entirely different place. We would not have Jock Kinneir and Margaret Calvert’s elegantly rational road signs, or the double-arrow logotype with which British Rail displaced the heraldry of its predecessor, British Railways.

Britain is a country that is deeply ambivalent about its place in the modern world. The nation that made the first Industrial Revolution had been so horrified by the experience that it embraced the nostalgic cult of the country cottage like no other culture. It’s an ambivalence that lingers. Britain, after all, is the country in which Sir Reginald Bloomfield, president of the Royal Institute of British Architects in the inter-war years, could describe what he insisted on calling ‘modemismus’ as an alien plot. And it was a country in which the director of the Tate in the 1930s refused to certify Picasso’s work as art for the purposes of avoiding import tax.

The British response to the startling eruption of smooth-skinned modernist boxy white concrete houses such as Mendelsohn and Chermayeff’s Chelsea house in the 1930s, and its Gropius-and-Fry-designed neighbour on Old Church Street, was encapsulated by Evelyn Waugh’s sinisterly comic invention, the fish-eyed Walter Gropius figure Professor Otto Silenus in A Handful of Dust. Silenus is discovered by Margot Beste-Chetwynde ‘in the pages of a progressive Hungarian quarterly’ and is hired to replace the Gothic Revival family home ‘with something clean and square’. ‘The problem of architecture as I see it,’ says Silenus, ‘is the problem of all art; the elimination of the human element from the consideration of form.’

It was only when modernism was domesticated in a pincer movement by Terence Conran and Paul Smith that Britain really took to it. And modern lite is now to be found in every branch of IKEA and Pizza Express.

If modernism was dead, and postmodernism was manifestly even deader, what was left to Charles Jencks but to look for another alternative. According to Jencks, ‘the New Paradigm’ is the next big thing for architecture. It is the aesthetic theory he has put forward in an attempt to make sense of the wave of buildings that looked like blobs of oil, desert dune landscapes and train wrecks that rolled across the Western world at the start of the twenty-first century. Jencks brewed up a blend of ideas on the edge of science and mysticism taken from the fields of number theory, and new thinking about biology, geology, astrophysics and Gaia.

Given that we now understand the nature of the universe differently from how we saw it fifty years ago, why should we cling to the right angle when we build, when nature has different ways of organizing itself? This, according to Jencks, is the idea that unites the shattered fragments of Daniel Libeskind’s Imperial War Museum in Salford, Frank Gehry’s sculptural shape-making in Bilbao and Zaha Hadid’s opera house in Guangzhou, even if it sounds a lot like the same counter-cultural primal soup from which Jencks’s original big idea, postmodernism, had emerged. And underneath Jencks’s passions you sense he is driven by that anxious quest every critic experiences, the search to find objective reasons to justify what remain the unquantifiable, unjustifiable subjective questions of taste. At heart, Jencks loves curves and lime-green paint more than glass boxes and white walls. If you don’t share his tastes, it’s hard to subscribe to his view of the significance of postmodernity.