Play the Part: Master Body Signals to Connect and Communicate for Business Success - Gina Barnett (2015)

Part I. THE STORIES OUR BODIES TELL

Chapter 2. Have a Heart

“When the heart speaks, the mind finds it indecent to object.”

—MILAN KUNDERA

The first few minutes of my initial coaching session with Bruce progressed in a straightforward and typical fashion. I introduced myself and told him how I work and asked what he was hoping to achieve from the engagement. He discussed his challenges in running meetings and getting traction from his reports. “There’s just so much resistance, and people always have excuses as to why they’re not doing what I ask.”

We discussed his background, and as he spoke, I noticed certain themes: how goal-driven he was, how he’d never before experienced so much oppositional behavior, how successful he’d always been—in school, sports, and business. How humble he wasn’t! When I spoke, he interrupted, contradicted, or ignored what I had to say. When he wasn’t speaking verbally, his body was speaking volumes: a shaking foot, a quick dismissive shake of the head, a downward curl of his lips. At one point, I gave up attempting to get through and decided to just hold my tongue and observe. At the end of this first meeting, I removed the DVD that had been recording our conversation and held it out to him.

“Well, Bruce. This has been an enlightening session for me, as I can see why you are encountering so much opposition.”

“Yeah? Why’s that?”

“Well, for one, you interrupted me every time I spoke, cutting me off mid-sentence with defensive, self-justifying arguments. Secondly, your behavior is smug, self-satisfied, and arrogant, and I’ve no doubt you are making the people who report to you feel insignificant and belittled.”

Without a word Bruce snatched the DVD from my hand and stormed out of my office.

People tell me I tell it like I see it, which can be good or bad, depending … But I’d made a decision when I “told” it to Bruce, and it was calculated. On one hand, his behavior was truly obnoxious—arrogant, defensive, and self-righteous. On the other, he was scared, and I knew it. I also knew that I really didn’t want to waste my time with someone who truly believed he had nothing to learn and was there merely to check off a box on his performance review. I called out to his retreating back, “If you’ve got the balls, watch the video.”

My heart was going like a rocket in my chest. I’d done something I almost never do; I aggressed on a client. I was as hostile and nasty to him as he’d been to me. My very words went against everything I hold dear about my work, which is to approach all with an open heart. I work constantly not to judge but to listen. I’d broken every rule in my book. I’d said those things not to be mean, but in an attempt to crack open his defenses and, I hoped, hold up a mirror to how he’d treated me and clearly was treating others. I knew I’d taken a big risk and perhaps a regrettable one, but I’d trusted my gut, and as much as I disliked his behavior, I still was coming from a good-hearted place. I assumed that would be the last time I’d see Bruce.

Three weeks later my phone rang. When my assistant told me it was he, I was quite surprised and prepared myself for the inevitable harangue. “This is Gina,” I said coolly.

“Bruce here.”

“Hello. How are you?”

“I just wanted to tell you something.” I took a breath to prepare myself. “I have never been spoken to the way you spoke to me. For weeks I was furious, and actually fantasized about hurting you physically and professionally.” There was a pregnant pause. I waited. “And then I looked at the videotape.”

“And?” I asked

“Who would ever want to work for that asshole?” Bruce replied. “When can I see you again?”

“Wow,” I replied. “What courage for you to call and tell me this! That’s fantastic, Bruce. I’d be thrilled to keep working with you.” And it was true. And here’s the amazing thing: when that man walked into my office a few days later, his eyes were literally transformed. We went on to do amazing work together, and he grew into a person I deeply cared about, admired, and even loved.

Having a heart means coming from a place of generosity and giving, but that does not mean being protective of another’s defenses. Always respect defenses, as they are deep-rooted and embedded for complicated reasons. But respect comes in many forms, and if you come from a place of genuine caring, you can say difficult things to people, in the hope of genuinely connecting. Again, it is important to be truthful regarding how your biases impact your “opinions” about others.

Defenses and defensiveness live as powerfully in the body as they do in behavior. People who feel compelled to defend themselves, who perceive differing opinions as assaults, embody a posture that will protect against those perceived assaults. They can carry excessive neck and shoulder tension (often accompanied by clenched jaws, furrowed brows, and tight forearms). Ready to spring into action to “defend,” they are taut all over. Such habitually high-strung protective posture creates rigidity; as goes the body, so goes the mind. As with all personal histories, defensiveness may be a chicken-or-egg situation. Is someone defensive because of early childhood trauma? Perhaps. Assaults or insults experienced when 3, 9, or 15 are ancient history and no longer present. And yet by having the body and the subconscious continue to carry and exhibit that history, defensive types often re-create situations in the present that mirror those early childhood traumas. This then keeps the need for defensiveness alive. The cycle is complete. How to break that cycle via the body and an open heart is what we’ll explore.

THE HEART

When an actor prepares for a role, he or she may write an imaginary autobiography of the character. The actor does this to dig into the historic underbelly of what might have made the character behave as he or she does. This exercise is particularly useful when playing a villain. The actor needs a backstory to explain the character’s dangerous or outright hateful actions because the job of every actor is to play the character with full commitment and no judgment.

To fully embody an “other,” an actor must suspend his or her opinions on the character. No one thinks he’s a bad guy. Essentially, people believe what they think and do is right, and it’s the other guy who is ill-informed or biased. That’s how we are. By writing an autobiography, the actor is opening his heart to the character in a way that doesn’t excuse bad behavior but seeks to unravel the mystery of its causation. Might one be able to do this in the workplace? Might a nonactor be able to imaginatively step into the mind, heart, and soul of another?

When I teach my corporate communications workshops, I sometimes ask clients to close their eyes and imagine someone they deeply admire, either from their personal or work life or from public life, history, or even fiction. As they think of that person, I ask them to imagine his or her voice, the way that person moves, gestures, listens, laughs. I ask them to picture the person’s hair, shoes, hands. Usually within seconds there is a subtle but absolutely discernible shift in how the client is breathing, sitting, and just “being.” Why? Because the client has an open heart to that individual and can allow that essence to be manifest within him or her. I sometimes then ask the client to present or converse with me not “as” the character, but as the imagined character “might” communicate. The transformation is immediate. Still oneself, but having permission to embody someone deeply admired, something amazing happens. It’s as though the client’s insides shift. The heart is open to that admirable person and thus to that part of the self, to the aspirations one holds for oneself. My question is, can we not do this with everyone? Must we only be able to open our hearts to those who mirror our own values? Can we not open our hearts to all?

TRY THIS: EMBODIED ASPIRATION

Imagine someone you deeply love or admire. Close your eyes and picture that person as fully as possible—his or her walk, voice, gestures. Open your eyes and walk around your home or apartment as him or her. What do you notice? How do your thoughts change? How do you move?

TRY THIS: EMBODIED ICK

Now let’s do the exact same exercise with someone you dislike or even loathe. Imagine the person so thoroughly that you can briefly become him or her. What happens?

If you gave yourself permission to do the above, excellent! What did you discover?

It is well understood that people repeatedly re-create the same dysfunctional patterns: they’ll date people who on the surface seem wildly different but underneath are practically interchangeable; they’ll jump from job to job but invariably find the same “impossible” boss. Repetition compulsion is a psychological term, but it lives in the body as well. The frequent result? When a body is chronically defensive, it often attracts aggression. While it’s not irrelevant how, when, or even why the defensiveness originated, what is crucial is the recognition that it lives on in the body and through the body. Anxiety, fear, self-judgment—all of these find a home in the body.

What is an open heart? How can having an open heart impact your ability to connect, listen, or lead? Will an open heart make you weak or vulnerable? A target? Too easily swayed? A pushover? How can you balance an open heart with difficult and often painful decision making? How can you achieve an open heart toward someone you passionately dislike or disagree with?

Years ago, studies found that doctors who had made bad clinical decisions and had terrible bedside manners were sued for malpractice with much greater frequency than doctors who’d made the same level of clinical errors but who had good patient relations. Patients were far more hesitant to sue the doctors they liked and who they felt “cared” for them, irrespective of the doctors’ grievous errors. Why would someone whose life was put in serious jeopardy by a bad medical decision not seek recompense merely because the doctor had a good bedside manner? Because everyone makes mistakes, but coming from a genuine place of concern clearly makes those mistakes more forgivable. Why? Because we are emotional beings. We are relationship beings. We build trust through our interactions, our behaviors, how we listen, and how we lead. Welcoming any person with an open heart, and by that I mean nonjudgmental, respectful acceptance of the person’s unique self, requires the willingness to let go of one’s own sense of righteousness.

How to do that? Behavior, the product of numerous factors—history, upbringing, family, genetics, ideology, to name a few—is enormously influenced as well by self-conception. There are self-proclaimed experts who feel no need to define nor defend the decisions they make. “I’m right” is more than sufficient. But self-conception itself is a tricky and moving target. One day you wake up feeling “I’m a super hotshot,” the next “I’m a lowly worm.” Both may be true and false. (Extremes on any end of the spectrum are highly suspect.) But true or false, fluid or static, how we think of ourselves greatly determines how we behave. These behaviors can be singular or collective. Collectively, in the Jim Crow era, whites thought they were better than blacks. Nazis thought Aryans were a superior race. The tzars of Russia thought they were demigods and behaved with ruthless impunity. As individuals, many people vacillate between superior and inferior self-conceptualizations. Supermodels will think they are gorgeous one day and hideous the next.

Self-conceptualization is also the result of numerous influences—language, culture, gender, family history, relationships, religion, and actual neural patterns. When the goal is to come from an open heart, toward oneself or toward others, one of the first steps is to identify how you self-conceptualize.

TRY THIS: THE LIST OF YOU (Part One)

Write a list of all the ways you think of yourself. All of them, the good, the bad, and the ugly. Don’t do this in one sitting, but keep the list updated and alive for a week or two; and as you notice how you think of yourself, jot it down. Put the list away, and a couple of weeks later, give it a look. Ask yourself how many of the ways in which you think of yourself are based in reality, history, what your parents, siblings, teachers, classmates, friends, previous partners, spouses said about you. Identify which ways actually serve your growth now as an evolving person. How many are ancient, vestigial, inherited, out-of-date? If you created the judge journal as suggested in Chapter 1, do you see any parallels?

TRY THIS: THE LIST OF YOUR NEMESIS (Part Two)

Identify someone from work who really annoys you. Write down what about that person makes you angry. Put that list away. After a few days compare lists and see if there is any relationship between that person’s negative traits and how you self-conceptualize. Frequently the most annoying behaviors in others mirror aspects of ourselves with which we also struggle. Those traits reflect the very things we dislike in ourselves, setting up a dissonance similar to two musical notes that don’t mesh.

The first step in attempting to live with an open heart is to exhibit one toward yourself. We are all incredibly imperfect. We are all in a state of constant flux and change. We are all guilty of envy, rigidity, stubbornness, judgment, inferiority, superiority. No one is perfect, and no one is anything but a continuously changing, vulnerable, imperfect being of accumulated thoughts, habits, and behaviors. We are all living within our very private conception of reality and struggling to make some kind of meaning out of this random thing called existence.

We all know we’re mortal, but few of us actually believe it. But if you live with the fact of your own mortality at the top of your mind day in and day out, it is virtually impossible not to feel your heart crack open. Life is so terribly brief! An open heart bypasses the labeling of oneself and others. It becomes where you start with people, not where you end up once you know them. It changes how you greet people and how you perceive their childish, ego-driven, faulty behaviors. As you accept and forgive your own frailties, those of others become far less irksome.

TRY THIS: OPEN HEART

Relax your shoulders completely. Float your head. Take a deep breath, close your eyes, and put all your awareness into the center of your chest. Let it soften and open. Whatever and whoever come to mind, soften the heart. Literally feel that part of the body get very, very soft and warm. Imagine it glowing, emitting a pale light. If any memory or upcoming stress comes to mind, just relax the heart. Keep breathing; keep softening; keep breathing; keep softening. See what that feels like. Notice, if tension creeps back in, where does it go? Soften the heart. Breathe. Soften the heart. Smile, not in a fake or forced way, but gently. Soften the heart. Melt the hardness away.

Can one do this at work? On the mean streets of a city? At the gym? Look around you in any of these places. Compassion, empathy, the ability to imagine an other, irrespective of whether or not you like the person, is the work of the heart. It is easy to love those whom you admire; it is hard to be open to those who deeply annoy and may even threaten you. But the latter are those who demand the leap of empathy.

If you really struggle with a colleague or manager with whom you simply cannot get along, ask yourself, at what age do you think that person is emotionally “arrested”? When I hear stories of dreadful office politics, the endless jockeying for power, attention, and real estate, I immediately think of junior high and that stage of maturation. Many professionals look and sound like adults, but scratch the surface and emotionally they are stuck at 3 years old, or 6, or 9, or—heaven forbid—13! It’s undoubtedly a challenge to have a boss who possesses genius for an area of expertise but the emotional maturity of a 7-year-old. But understanding where someone may be stuck is the ticket to navigating that person’s fragile ego and sense of self. Empathic intelligence, compassion, and open-heartedness are all admirable goals, but in truth they are where we must begin with each other. It takes work, but it is well worth the effort.

Sometimes, despite all we do, we simply cannot crack the code of someone’s bad behavior, nor can we stop being reactive to it. What then? There are several options: Observe where your reaction goes in your body. Where do you get tense? Belly, chest, jaw, back, head? Develop the practice of noticing quickly and often how someone else’s triggering behavior impacts your body. Does the person make you feel like you want to run away, duck and hide, or beat him or her up? Where does that impulse reside? In your legs, shoulders, arms? Once you notice what happens in your body, focus all your energy into calming and relaxing that area of reactive tension. Breathe; count to 10. Do nothing. Feel it. Just observe. Relax the areas and keep breathing into the tense areas, perhaps even softening them. By breaking your body’s reactive habit, different, more tolerable responses to the person might emerge. If all else fails, it is time to make an honest assessment. Behaviors can change, but personalities are pretty much fixed. There are personality types that simply cannot work successfully together. It’s not a failure; it’s just how it is sometimes. If that’s the situation in which you find yourself, it is time to seek alternatives.

What is the impact of the heart on the words we use? Right speech is a Buddhist concept that aligns compassion with the words we choose and the thoughts we think.

TRY THIS: RIGHT WORDS

Before you speak—before any words escape your mouth—ask yourself, are they kind? Are they necessary? Are they true? Begin with kindness and see where that leads. Helpful critique can be kind. How it will be heard is something to think about before offering it.

THE VOICE

In Chapter 1 we explored the impact of head-neck alignment and posture on how it makes you feel and how it impacts the way you’re perceived. I touched a bit on how the voice is affected. Now moving on from the metaphorical aspects of “having” a heart, I’ll take a deeper dive into the voice as it moves through the chest region. Indeed, it is impossible to discuss having an open heart without addressing the voice.

The voice mirrors and in many ways contains the life force. But almost no one—with the exception of actors, newscasters, preachers, and politicians— focuses on the voice with the proper attention. Defenses that seize the body can create tension in any number of places, but because the voice is such a profound manifestation of the entire instrument, it often manifests there. Take a moment to imagine any loved one and the way he or she sounds when excited, or sad, or suffering from an illness. Think of the sound of children when they play or are scared. Recall how, if you’ve ever read to a young child, you exaggerated the words, tune, and tone as a way of expressing emotion in the voice. Vocal signature is the manifestation of each person’s unique style. Energy, strength, health, emotion, vitality—these are just a few of the things communicated by the sound of the voice.

Nasality, a flat droning monotone, filler sounds and words, vocal lift (that irritating habit of ending a statement with a questioning lifted pitch on the final words), poor enunciation, a too rapid pace, repeatedly dropping volume at the end of sentences—all these and many more unconscious vocal habits can totally misrepresent your knowledge, authority, and gravitas. Conversely, vocal mastery can greatly enhance presence, leadership, and the ability to connect. A voice should be easy to hear and understand as well as pleasant to listen to.

The voice is the result of torso and body shape and is affected by the breath, head-neck alignment, mouth, throat, jaw, and sinuses. Improper placement or chronic tension (due to defensiveness or for any other reason) anywhere along the route of voice production will impact how sound exits the body. Think of a cello; all of it is essential for the richness of tone, timbre, pitch, and volume. So in considering the voice, it is vital to understand the structure and connectedness of all aspects of vocal production, of the instrument that is your body.

An engaging, warm, lively voice is the result of linking feeling with intention via a relaxed body.

TRY THIS: TUNE IN

Turn on the radio, close your eyes, and really listen hard as you tune in to the announcer’s pace, volume, tone, and pitch. Notice how a broadcaster will use variations of all of these elements to indicate what’s most critical, the end of one segment, and the beginning of another. Focus on how he or she puts volume and emphasis on key words to indicate what should be noticed or remembered.

TRY THIS: STRESSFUL OR SOOTHING

Next time you’re sitting on a park bench, at a cafe, or in a restaurant, close your eyes and notice the voices of those around you. Which ones make you feel agitated or stressed, and which calm you down? Do you see a pattern?

TRY THIS: WET DOG TALKING

Like a dog shaking off water, shake all over while speaking your name, address, and phone number or singing a simple tune like “Happy Birthday.” Notice how the voice quivers and shakes as well. Why is that? It is impossible to separate the voice from the body, and it’s essential that the body be as relaxed and centered as possible for the best vocal production.

Shallow-breathing, fast-talking, poorly enunciating speakers are difficult to follow not only in terms of the content they deliver, but more importantly because of the agitation and discomfort that they evoke in the bodies and minds of their audience. It is incredibly difficult to listen and absorb information when a speaker’s delivery is choppy, monotone, littered with filler, or poorly enunciated.

Audiences want speakers to succeed. They worry when someone flounders while presenting. (When I say “audiences,” I’m not only referring to large crowds. An audience is anyone on the receiving end of your communication.) But as much as audiences crave clarity of exchange and successful presentations, our pattern-seeking brains are instantly distracted and drawn in by a speaker’s flaws. People have to work hard to tune out such things as filler words or vocal lift. That tuning out results in attention being divided and in reduced content retention. Pace will set off a response in an audience, too. If the pace is too fast, it will create a kind of agitation, and if too slow, it will lull people to sleep!

Susan Cain, the bestselling author of Quiet, has written about our work on her TED Talk. Tip #6 from “Seven Public Speaking Tips” (www.psychologytoday.com/blog/quiet-the-power-introverts/201109/seven-public-speaking-tips-coach-ted-speakers-and-ceos) is “If your voice is soft or high, try this exercise. Inhale. Open your mouth dentist-wide, and say ah in a low tone, holding your belly as if you expect it to vibrate (it won’t.). Gina has to keep reminding me to keep my mouth wide open, because this feels so impolite to me. All of Gina’s exercises feel impolite, come to think of it, which is no doubt why I’m sitting in her office in the first place.”

I love Susan’s remark about my exercises feeling “impolite,” as so many things I ask of my clients force them out of their comfort zones. If you are an introvert, it will feel very strange to speak with greater volume; indeed beyond strange, it may even feel rude. Anything outside our usual range of motion, gesture, and volume may initially be experienced as “wrong.” Once a habitually quiet person discovers a more robust, engaging voice, it is often supremely liberating. Beware those internal assessments (impolite, rude, wrong, unladylike, pushy, etc.) that hold you back from experimenting with different ways of experiencing your voice. Sometimes it is essential to push through the discomfort of a deeply ingrained limiter to find a new and more professionally aligned voice.

Problematic vocal patterns and voice production can also be the result of linguistic insecurity or emotional or psychological trauma. A British client—a lovely, fun, open woman working in Germany—received feedback that she was intimidating. I could not figure out why, as she was anything but. By sheer luck one day, I happened to be in her office when she answered the phone. No pleasant smiling “Hello,” but a barking, harsh, very intimidating “Yah!” was her greeting. Bingo! Problem solved. Before her callers could even introduce themselves, her voice was telling them, “Be quick; I’m busy. You’re interrupting me. Get to the point.” German was not her first language, and by barking out her “Yah,” she was unconsciously attempting to cover the concern she had regarding her language insecurity.

The voice contains one’s history, culture, regional sound, psychological tics, and traps. It carries not only your tone but, more critically, your spirit and message. The physical sound of you exits your body and vibrates the eardrums of others, and what you say impacts their minds and hearts. Do you have a voice that speaks up, manifests your passion, courage, warmth, humor, and intelligence? Is there a disconnect between what you say and how it sounds? If so, that sets up an immediate, unconscious confusion in the mind of your audience. It is like static on the radio, and it’s almost impossible to ignore. Vocal lift is a perfect example of this kind of split. This vocal-style pattern, making everything sound like a question, has become ubiquitous over the past few decades. It significantly derails a speaker’s authority. In addition to being annoying, it’s an unconscious “ask” instead of a confident “tell.” When a declarative statement ends with vocal lift, it misrepresents the speaker and confuses the listener.

Tone is also a critical aspect of the voice. Tone is always aligned with intention or the goal of the communication. All communication is driven by moment-to-moment shifts in tone and intention.

TRY THIS: TONE TALK

Say “Sit down” as (a) a demand, (b) an invitation, (c) a plea, and (d) a question. Observe how the voice changes according to the intention behind those two simple words.

Entire books are available on the voice (see the list in Appendix C). But as far as “having a heart” is concerned, begin to observe your voice and ask yourself, “Is my delivery serving my role, my messages, and my heart?” It’s vital to work consistently toward a vocal presentation that is fluid, alive, varied, and appropriate to the goals of the exchange. Ask yourself, “Is there warmth in my tone? Is there melody and pitch variation? Am I speaking at the proper pace for my audience? Do I leave room for silence? Am I too slow, too fast, using vocabulary that will make connections or be off-putting?” Keep in mind that brains seek the unexpected and pay more attention when it occurs. Variation of melody, pitch, tone, and pace will far more effectively engage your audience, while a monotonous, flat, repetitive style of delivery will surely impede connection.

TRY THIS: SUBTLE SUBTEXT

Take the sentence below and read it aloud, placing emphasis on the underlined word:

There is nothing in this store that I want to own.

There is nothing in this store that I want to own.

There is nothing in this store that I want to own.

Notice that by placing the emphasis on different words, the subtextual meaning and message of the sentence changes. Emphasis can be created by increasing the volume, by lifting or dropping the pitch on a word, or by pausing before or after a word. Observe the subtle changes in meaning that can be communicated. The exact same sentence can deliver widely varied subtextual intentions just by varying the emphasis placed on different words.

When writing a presentation or just speaking off the cuff, never underestimate the impact of vocabulary. One wrong word in a certain context can have significant ramifications not only on your message but on how you are perceived. I’ve witnessed entire negotiations fall apart due to a wrong word choice! I had a client who’d come to work in the United States from another country. He was creating a lot of problems by “ordering” his reports, saying, “You will do this; you will do that,” or sometimes, just “Do it!” When I mentioned that kind of direct order can backfire depending on the recipient and that he might soften his approach with different individuals, he asked me what words to use. I suggested, “Let’s,” “How about,” “Could we,” “Have you thought about?” He barked at me, “But that is so weak!” He was unable to make the shift to a more inclusive vocabulary, and unfortunately he was let go. Tone has impact. Words have power. Choose yours with thought and consideration. Whether the goal is to connect, to lead, to inspire, or to enforce, it’s imperative to have a rich, multilayered vocabulary that can work for the specific situation at hand.

The opposite spectrum concerns weak word choices. A client reported that she had an upcoming meeting where she’d have to present something about which she didn’t feel 100 percent certain. “I’ll be out over my skis” was her expression. “Off-balance. And I notice that in those circumstances I tend to use weaker verbs and less forceful language. I back off my own recommendations because I’m not quite certain of them. I use words like ‘maybe,’ ‘could,’ and ‘I think’ too much.” Word choice is often a profound indicator of how grounded one feels. If uncertain about a subject, it is far better to lead with that truth than attempt to fake it with unconscious word choices that diminish your authority or send subtextual signals of insecurity. If you habitually use words that send those signals, even when you do feel secure regarding the subject matter, it is best to eliminate them from your vocabulary entirely. Practice saying the message out loud to find the words that support your message and do not undervalue it.

TRY THIS: SUBTLE TEXT

Write a directive, such as, “Finish the report, and have it disseminated by Friday at noon.” Now rewrite it, considering how you might change certain words depending on your audience. Write it as it would go to your manager, your report, or a colleague. Pick a different colleague or report and rewrite it. Rewrite it as if it were going to a colleague in a foreign country. Were certain words more appropriate for a given audience or a given recipient’s personality? Do you have a sufficiently robust vocabulary to make those subtle changes?

Now, take a more challenging communication and explore how, by varying the vocabulary, you might achieve different outcomes. Writing, as they say, is rewriting, and effective rewriting more often than not hinges on a solid grasp of the power of words: connotation, denotation, nuance, subtext, and cultural resonance.

We must constantly keep enriching our word choices and pushing ourselves to not rely on “packaged” phrases. As someone who spends a great deal of time hopping in and out of various corporations, it’s fascinating to notice the “approved” cultural words that, like any meme, are said over and over and over again. These endlessly repeated words become trite, lifeless corp-speak, empty of meaning and devoid of power. It’s essential for nuanced, audience-specific communications to embed novel words that capture the hearts and minds of your listeners.

One final word on vocabulary: different from filler sounds, like “um,” but often serving the same purpose is “habit speech,” words that are repeated unconsciously. “So,” “I think,” “Look,” “You know,” and “Like” are common. People have their unique repetitive verbal tics. Both filler and habit speech are ways that the mouth relies on sound to buy time while the brain is searching for a lost word or working to pull an idea together. The challenge with these unconscious sounds is that they can so litter the content that people begin to focus on them rather than on your ideas.

TRY THIS: HEAR YOURSELF

It’s a good practice to occasionally record your voice so you can evaluate it objectively. People initially dislike the sound of their voice, as we all are accustomed to hearing it as it resonates within the bones of the skull. It sounds thinner and higher “outside” the head, but you can get used to it. Record your end of a phone call or long conversation and listen for filler words, habit speech, tone, and pitch variation. Ask friends and loved ones what about your voice is great or annoying, and pay attention to that part of you that, in some cases, is the only part others may ever know. Finally, make sure that your tone is aligned with your intention so that there is no confusion between the content and the goal of its expression.

If having recorded yourself, you notice a lot of filler sounds or words, the best way to limit or rid yourself of them entirely is to slow the pace of speech by just a tiny amount. Sometimes the mouth moves faster than the brain, or conversely the brain speeds ahead of the mouth. We reach an intersection where we need to either find the right word or catch our mouth up to our brain. We “fill” that moment of silence with sound. By slowing down the pace, we’re better able to anticipate the intersection and often find the word when needed. The best way to slow our pace of speech is to enunciate more distinctly. It is hard to speak rapidly if the mouth fully wraps around all the sounds of a word, in particular, the end sounds.

TRY THIS: LAZY LIPS WORKOUT

If upon listening to your recorded voice, you notice that you mumble or have an abundance of filler sounds or repeated habit words, the best way to correct this is to slow the pace by enunciating more fully. Read aloud very slowly, enunciating in a very exaggerated way the beginning, middle, and end sounds of each word. Do this for one or two minutes a night, which is about all the lips and mouth will be able to tolerate. This is akin to weight lifting for the lips and mouth and is exhausting, but it works like magic! We all tend to have very lazy lips!

TRY THIS: FILLER BE GONE!

Say aloud your filler sound or habit speech very, very slowly. Repeat it 10 to 20 times to train both the brain to hear it and the body to feel the muscle recruitment that makes it happen. By repeating it extremely slowly and training the brain to hear it, you can stop it before it happens. Follow this by repeating just the muscle movements that precede the vocalization of the filler sound. Often, for example, “um” or “ah” is preceded by what’s called a glottal stop. The base of the throat closes and obstructs the air flow. Feel that closing; repeat just that muscle movement over and over without making any sound. This will help the brain to notice just the movement, and then the filler sound can be replaced by a micro-inhalation. Do this in the morning after brushing your teeth. Repeat it daily for about 30 seconds over a week or two. By following this process, clients of mine have completely eliminated filler sounds. After you’ve gained mastery over this habit, repeat these exercises about twice a month, or the filler words will slowly creep back into your speech.

If, upon listening to your voice, you discover that your volume is either too soft or too loud, it would be good to ask others what their perceptions are. If they mirror your own thoughts, then you will want to adjust your volume. Additionally, I’ve found that for those who struggle with being heard or with getting traction from their comments, it can be something as simple as supporting the voice with a bit more power. The goal is not to feel as though you are pushing or yelling, but empowering the voice from the diaphragm. In the following section, I cover belly breathing, and following that is an exercise for increasing volume.

If you have any doubt regarding the power and influence of the voice, picture yourself sitting in a plane preparing for takeoff when the pilot makes the announcement. Imagine how you might feel if you were to hear a nervous, shaky, stammering pilot telling you to “sit back, relax, and have a nice trip.” Could you? Would you? As seasoned and calm as passengers may appear, deep down they are giving up all control of their destiny for the next several hours. That’s scary! Pilots know this. The only instrument a pilot has to send calm assurance to the passengers is that brief announcement. Calm, measured, warm—it’s all been practiced so that the passengers relax.

One final thing to keep in mind: as our world becomes increasingly reliant on non-face-to-face communication, vocal mastery will only become more essential. Your voice is your signature. It’s vital that it manifest your energy, warmth, smarts, and heart.

SHOULDERS

We’ve seen how head-neck thrust and poor posture can have significant impact on how you feel and are perceived. But what about just the shoulders themselves? Relaxed, upright shoulders with an open chest supported by a free open rib cage, all relying on the core strength of the abdomen, accomplish several things. One looks vigorous, open, robust, and able to take on challenges. Strong, relaxed shoulders and a lifted head greatly enhance a resonant open voice.

TRY THIS: FAN ARMS

Find a stool or chair without arms and sit in an upright position. Bend your arms and bring your elbows close in to the sides of your body. Notice the muscles between the shoulder blades, and very slightly engage those muscles. Float the head (imagine a string coming from the top of the head and going up to the sky, gently lifting you up. No yanking! No straining! Now, slowly, keeping the elbows by your sides, move the forearms outward to the sides (not forward) so that the forearms are perpendicular to the torso with the palms facing out. Then gently bring the forearms forward so that the palms are facing each other. Make sure the elbows stay tucked in next to your sides. Repeat five to seven times, making sure that the head stays lifted, is level, the chin doesn’t jut forward, and the stomach muscles are engaged. This exercise utilizes the muscles in the upper back and counteracts the poor alignment resulting from hours at a computer. It’s also excellent for opening the chest and shoulder area.

TRY THIS: THE BUTTERFLY

This exercise helps to open the shoulders and lead to a better head-neck alignment. Sit on the floor with your back against a wall and your legs extending straight out from your hips. Try to get your rear end as close against the wall as possible. Flex your feet by pointing your toes back toward your body; keep the legs straight and the thigh muscles engaged. The head should be touching the wall behind it and arms resting on the floor. As you sit in this position, gently bring the shoulder blades together. Hold this posture for two to three minutes.

TRY THIS: WEIGHTED NECK STRETCH

As you relax out of the butterfly position, keeping the chest lifted and open, drop the chin to the chest, bring your hands behind your head, and let the weight of the arms stretch the back of the neck. Take three or four deep belly breaths while holding that stretch.

When you consider the impact of posture on how you will be perceived, the reasons for good posture become immediately evident. Remember, the medium is the message, and when communicating, you are the medium. I had a client who had very slumped shoulders and such terrible head thrust that she required a thick pillow when lying on the floor. Her head simply could not reach the floor. After working to correct this situation, she called me to say, “I’m finding my voice!” I asked if she meant that her voice was more open and forceful. “Well, yes, that too. But I mean to say, I am speaking up! I realized that by being so slumped over, I was also not feeling the confidence to express my opinions. Now I am!” There’s that body-mind loop again!

THE BREATH

Good posture is needed for proper breath support, which is essential for the voice. Although this chapter focuses on the chest region, we’ll have to dive into the belly for a bit, as abdominal or belly breathing, the full expansion of the lungs that requires the belly to extend outward, is essential for proper voice production. Belly breathing is the restorative breathing we all do when we sleep and when we are relaxed. During the day, the breath immediately responds to any changes in circumstance. When nervous or stressed, we grip in the abdomen and take short, shallow inhalations into the chest. Often when I teach group seminars, I’ll ask the participants to take a deep breath. Most of the people in the room breathe into their chests and not into their bellies. Shoulders go up, chests expand. Belly breathing, restorative, natural, deep, and essential for a calm, centered approach to all challenges, is often the exception rather than the rule. If you have children, watch them breathe in their sleep. You will witness their relaxed, round little bellies expand and then flatten, just as yours does when you sleep. Developing the ability to breathe deeply into the belly even when stressed or nervous is a skill that can and should be mastered.

TRY THIS: BELLY BREATH

Stand up, with the hips directly over the knees and knees over the ankles. The feet should be hip-width apart. Don’t lock the knees; keep them soft. Float the head; again don’t yank or pull it upward. Just imagine it floating upward in a gently lifted way. Keep the shoulders relaxed and down. Bring the shoulders high up the ears and drop them two or three times. Yawn once or twice. Now with the jaw relaxed, posture aligned, breathe in through the nose, and as you do so, let the belly expand fully outward. It can help to put one finger on your belly button, and as you inhale push the belly outward. As you exhale, let the belly button go backward toward the spine, or help that action by using your finger to gently push the belly button in. The chest and shoulders should not move at all. If you get dizzy, sit and continue, but make sure you are sitting up on the sits bones and not slouching. If you find this almost impossible to accomplish, then lie down on your back and read a book or magazine for a few minutes until you are completely relaxed. You’ll notice that you are naturally breathing into the belly. Come to a sitting position and maintain that belly breathing. Stand and continue. If at any point when changing positions you find it difficult to maintain the belly breathing, return to lying down and start over. Be patient. For those who for decades have been chest breathing, this is a hard change to make. Keep at it, as the benefits—in stress reduction, energy, vocal power—can be huge.

Now that you’ve got belly breathing covered, below is an exercise that can gently and slowly build up the muscle to increase volume without yelling.

TRY THIS: CORNER SPEAK

Stand facing a corner with some reading material and read aloud at your typical volume for about a minute. Listen carefully so your ears and brain can assess the decibel level. Take one large step back and keep reading with the goal of achieving the previously heard decibel level. Read aloud for a minute. Do this for a few minutes each night for a week. On week two, repeat the above and step back two steps from the corner, again attempting to achieve the same decibel level, not by pushing or yelling, but by using the belly-breath support. On week three, repeat the above and step back three steps. Conversely, if you’ve been told that you speak too loudly, do the above exercise but in reverse. Start far away from the wall, attune your ears to hear the decibel level, and then step closer to the wall, lowering the volume accordingly.

Consciously working to slow down respiration when under duress has been shown to increase relaxation and tamp down the effects of adrenalin. The breath and heartbeat are instantly responsive to the sympathetic and parasympathetic impulses from the brain as it receives information from our surroundings. Developing mastery over the fight-or-flight effects on respiration is worth exploring, especially before a high-stakes presentation or communication.

TRY THIS: 10-SECOND BREATH

Relax the body and take a very slow five-second inhalation through the nose into the belly. If it is too hard to control the air coming in at that rate from the nose, then make a very slight opening in the lips. Exhale taking the same amount of time. Repeat six times. This can do much to help the body relax and focus, and it has been found to lower blood pressure and the levels of cortisol, the stress hormone.

TRY THIS: ABDOMEN VIBRATE

Relax the jaw and open the mouth very wide. Let the tongue come forward out of the mouth and stretch it gently forward. Now roll the tongue over the teeth as though cleaning them. Put one hand on the lower abdomen. Take a nice deep breath, keep the mouth open very wide, almost yawning-wide, and exhale on the sound of “hah.” The mental exercise, along with this physical one, is to imagine the lower abdomen vibrating on that deep “hah” sound emanating from a wide-open relaxed jaw. It’s very difficult to feel the hand vibrate while placed on the abdomen, but imagining it helps. Make sure you don’t allow the jaw hinge to close down. Keep the mouth very open and head placed correctly on the neck. Make sure your head is level and not tilted up or down. Repeat 5 to 10 times. Don’t think about volume, just vibration.

TRY THIS: CHEST VIBRATE

Continue the above and place your other hand on the chest. Repeat the relaxed, slow, deep belly-breath inhalation and now exhale on an “oh” sound. Don’t reduce the opening of the jaw; keep the jaw wide open and create the “oh” sound with the lips alone. You will most definitely feel that sound vibrating in your chest.

TRY THIS: TORSO VIBRATE

With the jaw still wide and relaxed, keep the hands where they are and move the vibration from belly to chest. Switch between “hah” and “oh” sounds over multiple inhalations and exhalations. Try them on different pitch notes, moving up or down a scale from higher pitches to lower ones, or vice versa.

In addition to being very relaxing, these exercises open up belly and chest resonances for the voice. They are also excellent to do before any presentation, as they will get you breathing deeply, increase relaxation, and sharpen focus.

TRY THIS: BREATH WITH ARM THRUST

This breathing exercise can energize the body and is a way to release stress. Sit straight with elbows bent and hands beside the ears, palms facing outward. As you inhale, vigorously thrust the hands upward, palms open, fingers spread widely. As you exhale, equally vigorously bend the elbows and pull the arms back down to your sides with the elbows bent and the hands by the ears. Repeat this 5 to 10 times. It energizes and focuses the body. It’s also a great practice for the mid-afternoon slump!

TRY THIS: GET THE PEANUT BUTTER OFF

Shake out all over, like a dog shaking water off its coat. Or you can do it in sections: raise the arms above the head and vigorously shake the hands, as though trying to get peanut butter off them. Bring the arms forward and shake the hands as if to say “go away” or “come back.” Drop the arms to your sides and shake the hands up and down, up and down. No wimpy shaking; really move with energy! Add the hips: shake them side to side or back to front. Stand on one leg and shake the other as though trying to kick off your shoe. Switch feet. Finish by vigorously shaking your whole body. This is a great way to release tension and energize the body. I always add some deep grunting like a sumo wrestler for added fun and tension release.

ARMS/HANDS AND GESTURES

People often worry about what to do with their arms when they present in a more formal context. “What should I do with my hands?” is the most common question I get when I do presentation trainings. My first response is to tell my clients to replace the word presentation with conversation. The more you experience any exchange as a give-and-take, the better chance your hand and arm gestures will be an organic part of that exchange. Gestures and speech are deeply intertwined, so the best way to think about any content delivery, even a highly structured one, is for your style to be conversational.

Arms and hands are wonderful parts of our instrument and can greatly enhance the delivery of any message. They can also be terribly distracting. When we’re tense, different tendencies appear: pounding the hands in rhythmic fashion, making chopping movements, conducting on the words, fidgeting fingers, rubbing fingers, gripping hands in front of the groin (known as the fig leaf position), keeping the arms frozen by the sides, hiding hands behind the back or in pockets. I’ve had many clients who were told early in their careers, “You use your hands too much,” and they’ve spent decades with frozen, lifeless appendages ever since. Also, as with other aspects of communication, arm and hand gestures can be very culturally specific. “I’m Italian” is one explanation I’ve heard countless times from those who not only gesture vigorously but almost cannot speak without moving their hands and arms. On the other hand, a client from Pakistan told me that in Pakistan men stand with their arms crossed. This is their natural and comfortable position. He confided to me in a meeting, “Now that I’m working in the United States, I’ve been told that that is defensive and closed off, that I should have my arms open or by my sides. The problem is, if I do that, I literally lose my train of thought. I cannot find my words.” Here is another stunning example of the body-mind feedback loop.

Language, speech, and gesture are all one connected system, not isolated parts. Studies have observed how infants’ gestures and early speech are deeply entwined, as both are driven by communications needs. Babbling babies will often move their arms in sync with the sounds emerging from their mouths. As their gestures become more refined, and as pointing or raising their arms is used to indicate “pick me up,” those gestures will then be accompanied by sounds. There is a mutual, flexible joining of gesture and speech that, once laid down, is almost impossible to decouple.

Whatever one’s heritage and history, arm and hand gestures need to be genuine, relaxed, and appropriate. They should align with your content and not compete with it. Eyes automatically go toward motion and are immediately drawn to pounding hands and fidgeting fingers. It is best to eliminate distracting gestures and seek those that organically support the content. But also its important to avoid practiced, preplanned gestures, as they invariably come off as fake.

If you’re really lost about how to let the arms express, the best choice is to bend your elbows and gently rest one hand into the other at midriff, not groin, level. That’s a neutral and completely acceptable position. Once relaxed, arms move naturally. Between movements allow the arms to return to that hand-in-hand position, or let the arms relax by your sides. It’s important that your hands are visible, so putting them behind the back is to be avoided. (Also, that position changes the shoulder line, thrusts the head forward, creating neck tension that can impact the voice.)

If your hands shake, a good technique is to use isometrics. By using the hand-resting-in-hand position, you can gently press the bottom hand up and the top hand down so that the shaking is diminished and that nervous energy is utilized by pressing the hands into each other. It should not be obvious and should appear relaxed. If you have a habit of putting your hands in your pockets, which is not recommended, try rehearsing while wearing pants without pockets. Explore where the hands can go without stuffing them out of sight.

Similar to recording the voice, the best way to see any distracting gestures and make the necessary changes is to videotape a rehearsal of you presenting. Seeing is believing, and by watching the recording, you can identify any habitual, repetitive, distracting gestures and work to reduce or eliminate them. A client with really large hands had a tendency to present with his hands held so high, they almost hid his face. I asked him, “Are you hiding your face or protecting it?” He had no idea to what I was referring until he saw himself on video.

“Hiding, no doubt,” was his reply. “I’ve always felt a bit uncomfortable about my weak chin.”

Some gestures are unconscious ways of hiding a part of ourselves, or used to distract the eye.

TRY THIS: HAND REST

To practice the best arm position for you, come to a standing position and let your arms go to your personal habitual position. Where do they go? Do you hold them behind your back? Put them in your pockets? To implement any change, it’s best to become aware of your habitual hand or arm position. Relax and let your hands drop to your sides with your arms hanging loosely. Now bend at the elbows and gently place one hand into the other. Try not to interlace your fingers or press the fingers from one hand onto the fingers of the other (forming a triangle). The latter position, spider hands, can appear quite tense. One hand resting in the other is a great go-to position, as you can easily gesture from there and return to it with no effort.

TRY THIS: HAND DANCE

If you are really at a loss about what to do with your hands, it is best to get out of your comfort zone and do something wildly out of your usual patterns of movement. If you tend to stuff your hands in your pockets, force yourself to speak with your hands held above your head. If you tend to go immediately to the fig leaf position, put your hands on top of your head. If you feel you gesture too much, speak with your arms crossed. These are exercises to help you break habits and interrupt usual patterns of movement. The goal, obviously, is not to actually deliver with your hands above your head. It is to break the habit and see where the arms and hands go once the entrenched habits are broken.

TRY THIS: HAND WATCH

Since hand and arm movements are such vital parts of our overall communication, it’s helpful to observe those who use gestures well. Watch closely those who use their hands effectively, who employ gestures that evoke the correct images, who use movements that lead the eyes and help tell the story. Additionally, since so many gestures are deeply embedded in culture, it is important, especially if you work in a global organization, to familiarize yourself with what may be unacceptable or rude hand gestures. Irrespective of culture, note as well those who use gestures that can be off-putting. Pounding, finger-pointing, fidgeting, tapping, unconscious repetitive rubbing—the list of what hands “tell” is remarkable, and it is wise to observe both effective and distracting gestures in others as a way of assessing your own.

A client who leads a team of over 30 people told me that he felt that many of them were not comfortable or open with him. As I listened to him, I felt myself feeling rushed and a bit anxious, and then I noticed his right thumb. His hands were folded on the table, but his thumb was constantly, and quite rapidly, beating up and down, sending a signal that my body read as “hurry up.”

“What is up with your thumb?” I asked him. He had no idea what I was talking about. “It hasn’t stopped moving since we began to talk. It’s been wiggling up and down constantly.”

“Really?” He took his hands off the table. Then, in an attempt to modify or control his wiggling fingers, he began to repeatedly run his hands through his hair. This was a replacement gesture and was equally disruptive. The source of his unconscious movements, what I call discharge movements, was energy bound up with tension. His body needed to move—a lot—but it had chosen repetitive, unconscious ways of doing so that created tension in me, and no doubt was doing so with his reports. As we began to unpack what may have contributed to the communication challenges at work, I decided to zero in on his thumbs. It proved to be the portal to a much deeper aspect of communication: how we mirror one another, which I’ll explore more deeply shortly.

One final thought on hands as a part of our communication in the workplace: it is important not to underestimate the power of touch. Context is all with regard to touch, especially in the workplace, as it is a sensitive and tricky subject. Nonetheless, touch has been demonstrated to have enormous impact on connection. It is the primary form of exchange between infant and parent and is indeed its own language. (Soothing, comforting gestures can calm a baby who has not yet acquired any speech.) Touch is also very cultural, as some societies are far more open and comfortable with it than others. With regard to connection and its appropriate use in professional settings, it is always best to err on the side of less is more. Many employee handbooks simply state, “Do not touch. Ever.” However, a firm handshake, a pat on a shoulder, a light touch on an arm, each of these can lead to a moment of exchange and trust. It’s all in the timing, the duration, and the degree of eye contact. As far as having a heart is concerned, a gentle touch can work wonders. That said, a handshake that goes mere seconds too long, with overly penetrating eye contact, can suddenly shift from kind to creepy. But to simply never touch as a way to prevent potential infractions feels somehow inhuman. We are physical beings, and it is up to each person to create the boundary that establishes his or her level of comfort. More critically, it is essential that no one feel anxious or uncomfortable when either the giver or recipient of a touch. Hands are such a vital part of our overall communication that forbidding touch completely seems a deeply limiting response to a very human need.

MIRROR GAME/MIRROR NEURONS

Books on body language frequently explore how we unconsciously mirror one another’s positions as a way to form connection and alignment. Some books even instruct readers on how to copy a counterpart’s position or body language as a way to engender feelings of trust and rapport. Using an organic, unconscious system that evolved over hundreds of thousands of years for a multiplicity of reasons as a way to manipulate trust is, in my opinion, highly suspect. But exploring our desires to mirror and understanding our mirror neurons as a route toward compassion are extremely important.

In 1963, in Improvisation for the Theater, Viola Spolin introduced her theater games practices and philosophy to the theater community and, years later, into the educational and arts community at large. As time went by, her inspiring methods reached well beyond theater training and early education applications and entered the fields of psychology and mental health. Today, many team-building exercises employed by corporations and trainers have their roots in Spolin’s games.

When I began studying acting at age nine, Spolin’s games were the vocabulary of the day. Weekly, I would go to a two-hour acting class that routinely began with a warm-up called the Mirror Game. What was this exercise? In Spolin’s words: “Player A faces Player B. A reflects all movements initiated by B, head to foot, including facial expressions. After a time, positions are reversed so that B reflects A.”

Simple enough. As the players become more focused and adept, the game moves to a more complicated level. In Follow the Follower, the players “reflect each other without initiating… . Both are at once the Initiator and the Mirror. Players reflect themselves being reflected.” The result is a level of riveting focus. The initiator-mirror relationship becomes indecipherable between the players. There is neither leader nor follower. The players begin to experience the self not as “the” self but as “a” self, to step physically into another’s reality of time, movement, intention, and sometimes even thought. It can be fabulously fun, sometimes a little scary, but no matter what, it’s an enlightening experience.

My weekly practice of the Mirror gave me insight into other people that was beyond words. By mirroring an other I was wordlessly learning the power of entering someone elses’ stance, expression, rhythm, indeed presence. As my skill improved, I experienced the awesome event when neither player initiated or copied, but when two distinct beings became synchronized. Talk about seeing things from the other’s point of view! The mirror exercise, so simple, is utterly profound.

(Years later, when I was an acting teacher myself, one of my first classes was with teenagers from an inner-city high school. I was 19. They were 14 and 15. They were a tough bunch. Some had been expelled for knife fights or throwing chairs at their teachers. I taught them the mirror exercise and listened as they came up with every excuse in the world not to do it. But once they stopped giggling, settled down, and became focused, an amazing thing happened. They began to experience each other not as dangerous or alien but as fellow humans with whom they shared unspoken kinship. These were troubled kids, defensive to the hilt, but the game, once they got into it, opened them up tremendously. Wordlessly they dropped their habitual defenses as they embodied each other. They experienced stepping outside of themselves and into others’ rhythms, movements, and expressions. They couldn’t get enough of the mirror game.)

Spolin’s exercise is a stepping-stone toward a critical skill everyone should aim to possess: become an other without judgment. The mirror exercise and, as neuroscience is discovering, our mirror neurons create the “merging of two discrete physiologies into a connected circuit.”

While mirror neurons work at the unconscious level and the mirror exercise is done almost exclusively in acting classes, what can those who wish to consciously master the art of “merging discrete physiologies” do? After all, actors spend years mastering the art of signaling, spend weeks in rehearsal to make their characters come across as believable and authentic. How can those who’ve never studied such methods hope to achieve mastery over their communication skills?

The very first step is to bring awareness of your own body into consciousness. That, in itself, is a practice that must be integrated into daily life. Before you can consciously begin to understand the nuances of mirroring, it is essential that during the workday you check in, routinely and frequently, and observe your own body signals. Where is tension being held? What is your jaw doing? Your belly, your feet?

Our bodies communicate all day long, frequently expressing what we repress. Listening, checking in multiple times a day to the signals being sent from oneself to oneself is a critical first step. Awareness of your own physical state will provide deeper insight into the physical and emotional states of those around you. Self-scanning is the best first step toward this end.

When I first started to coach actors, while watching someone work, I’d occasionally get sleepy. Initially, I thought that I wasn’t focusing well enough or that I was tired. But over time, I discovered that I tuned out or got sleepy when the performer was cut off, when he or she was just going through the motions, or phoning it in. The actor was putting me to sleep. Over time, I developed the skill of splitting my focus: watching an actor as acutely as possible while simultaneously listening to my body. If I got sleepy or restless or my mind wandered, it wasn’t because I was undisciplined or tired. It was because the person was faking it, or hiding, or being some how inauthentic. If, while watching, my jaw got tight, my breathing shallow, or my back stiff, I began to realize that my body was at some level mirroring what the actor was expressing or, more critically, repressing. (There’s actually a theater term called the butt switch. It refers to when the members of an audience as a single body unconsciously notice that their butts are falling asleep and need adjustment. When does this happen? Why would an entire group of people suddenly become aware of their discomfort? Because what is happening on stage isn’t holding them. Because it’s boring, ill-paced, or just plain bad. Even though an audience is made up of individuals, when they come together, they become akin to a giant brain, and they collectively know when what they are watching is not working. They may not have the vocabulary to say why, but they have the collective body smarts to feel it!)

So how might the mirror exercise be relevant to your workday? As humans, we are hardwired to observe each other in the most refined, minute, and instantaneous ways. In early human development, we needed to determine quickly if we were safe or in danger. Was the creature approaching out of the darkness coming to offer us something to eat or to eat us? Repeated miscalculations on instantaneous decisions of that sort would have had tragic consequences for the species itself! Additionally, for the survival of the tribe, we needed to instantly observe the bodies of those dependent on us. Was a baby crying because of hunger, sickness, discomfort, or boredom? Repeated incorrect interpretations of a baby’s cry would have had terrible consequences as well. These ancient skills evolved for our very survival. We learned to sniff each other and our environments out instantly.

The theater is relevant because it is an outgrowth of those very same observational skills. And while these skills are indeed hardwired, they are subtle and require updating, fine tuning, and increasingly subtle awareness. The initial practice and ultimate refinement of developing one’s own body awareness is a vital step toward understanding others.

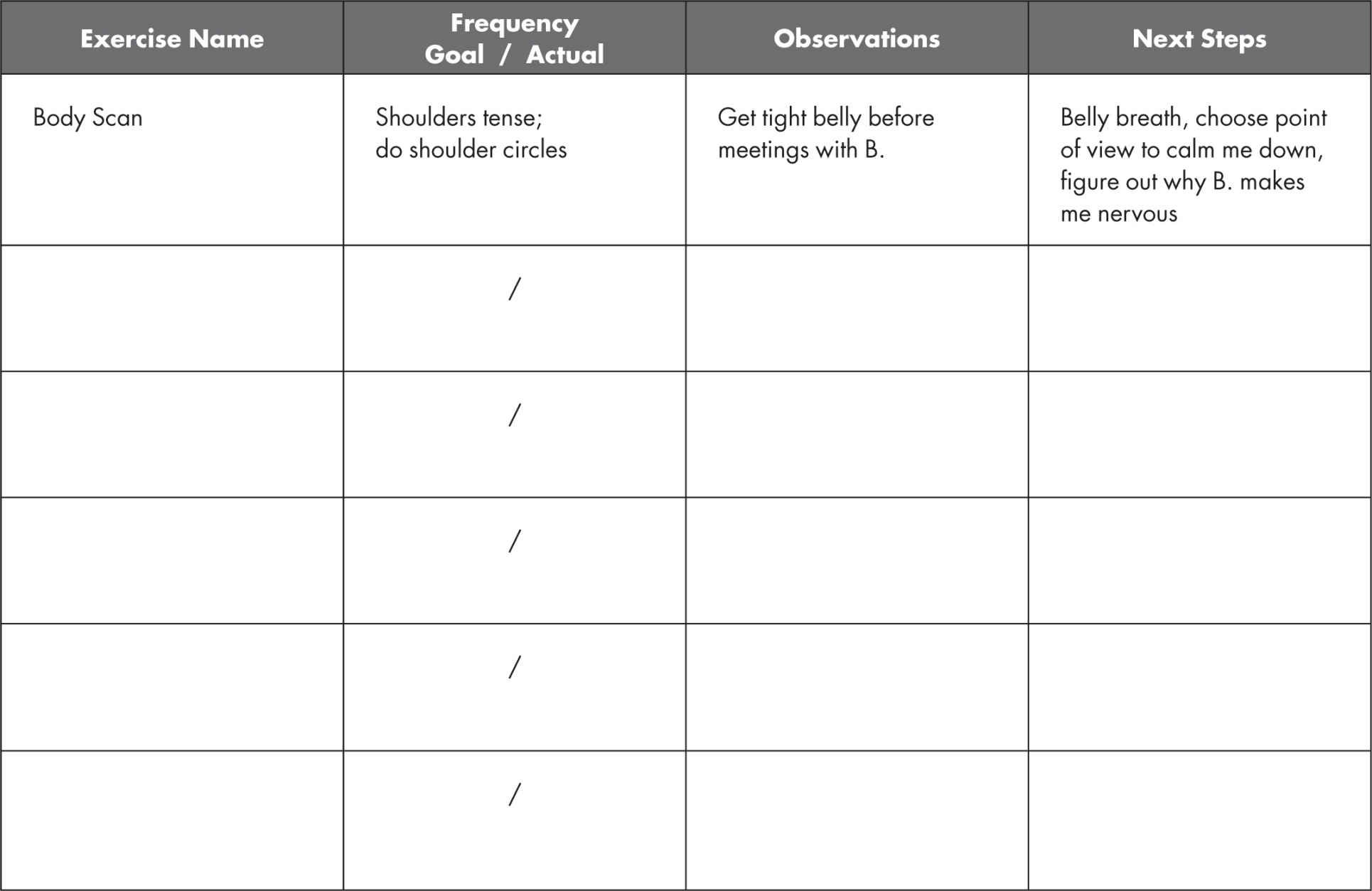

TRY THIS: BODY SCAN

As you sit with this book in your hands, take a deep breath and mentally traverse your body by focusing your attention on your feet and then slowly moving that attention up your legs, knees, thighs, hips, groin, belly, chest, shoulders, neck, and head. Don’t forget to notice your arms and hands. Where are you tense or tight? Are there zones or regions that feel deadened or, conversely, quite tingly and alive? Begin to practice this awareness randomly during the day, at your desk, while in meetings, or during conference calls. The routine of performing a mental checklist of the body is a profoundly enlightening exercise.

How to remind yourself to do this exercise? We have a multitude of technological devices—computers, tablets, cell phones—that can be set to vibrate, ding, or beep. Absent such things, there are Post-it notes or the age-old string around a finger. There will be resistance to “getting in touch” because we are so used to ignoring this thing we live in, taking it for granted until it tells us via injury, hunger, or illness to pay attention. The little voice inside rebels: “I have no time!” “I’m on the phone!” “I’m in a meeting” “I’m with a client!” But those are precisely the times to check in with what the body is doing and feeling. Body awareness can happen in the midst of any activity. All you have to do is shift your attention and check in. Initially you won’t notice all that much. But the more frequently you do it, the better and more subtle your awareness will become.

TRY THIS: BAG OF SAND

Stop and take a slow breath; having located from the previous exercise where the tension is, attempt to release it. Focus your attention where you notice tension, take a slow inhalation, and imagine that there is a hole at the surface of the body where you feel the tension; then, like sand seeping out of a hole in a sack, imagine with each exhalation that the tension is seeping out through that imaginary hole. The more you develop this practice of becoming aware of tension and releasing it, the better you’ll get at doing so. Ultimately, you’ll be able to do this in mere seconds.

Once you are able to fully feel your body on a more consistent basis, to have greater awareness of the signals you are sending both to and from yourself, it becomes easier to be sensitive to those coming at you from others. You’ll begin to notice when others are tense, when they are physically defensive, and when they appear to be listening but are in fact tuned out.

Occasionally, during communications trainings after a speaker has delivered a presentation, I will ask the audience if anyone’s mind wandered. Initially, people are reluctant to admit that, while physically present, their minds went elsewhere. I only ask when it is acutely clear to me not that the audience was bored, tired, or indifferent, but that the speaker was not really engaged. Invariably 80 to 90 percent of the people in the audience will admit that their minds wandered. I’ll ask, “Precisely when?” Again, invariably they will uniformly say, “Around slide three” or somewhere else quite specific. It is at that point that the speaker will then admit, “I didn’t really want to deliver that slide. It bored me,” or “I didn’t fully agree with it.” Mystery solved! The audience will tune out when you, the speaker, are not fully present or engaged. If you are bored by what you have to say, then how can you reasonably expect the audience not to be? Audiences know and feel this deeply, intuitively, and nonverbally. Developing the vocabulary to identify and define those behaviors within oneself only makes one more skilled at spotting them in others and becoming more adept at helping them. Additionally, I’ll often ask a speaker if he or she noticed anything about the body at that particular point in the presentation. Invariably the response is a tightness in the throat or chest or restless legs. The body was expressing what was being avoided. Bodies talk reams, if we would only listen.

The take-away here is that by developing the practice of tuning in to your own body signals, you’ll increase your skill at sensing those of others. By sensing others more acutely, allowing unconscious mirroring to become part of your communicative skill set, connecting with others will become easier and less constricted by judgment. On an even deeper and more consequential level, if your values are in conflict with something you must communicate, your body will at some level signal that, and others will at some level sense it. They may not be able to articulate it, but they will sense it.

The goal of an open heart, self-body awareness, and increased awareness of others—the mirror exercise, mirror neurons, neural Wi-Fi—goes beyond the ability to connect. It goes straight to the heart of being able to communicate with compassion. Why aim for this? Many reasons. Compassion, the ability to feel concern and care for another’s difficulty with the accompanying desire to help, not only aids the sufferer but enhances one’s own sense of purpose and engagement. By caring for oneself and others, we grow the muscle to better cope with distress overall. Perhaps this evolved over time as a way to ensure the survival of the species, but since we are all profoundly dependent on each other, it makes sense that concern for others’ welfare would impact our own sense of purpose. Empathy, or the ability to feel emotionally what another is going through, while also vital for our common humanity, can overwhelm or lead to burnout. This is especially true for people who are constantly surrounded by those in distress. Compassion—the impulse to help, serve, and alleviate— on the other hand, tends less toward burnout and more toward engagement. What better way is there to connect and communicate effectively than through engagement?

The antenna deep inside all of us gathers signals from both ourselves and others, but it takes practice to tune in and develop it. Increased attunement leads us to make assessments and decisions in the gut before they happen in the brain, and that is where we’ll go next.

Chapter 2: Have a Heart

Review Exercises

Heart

✵ Embodied Aspiration—increase confidence

✵ Embodied Ick—emotion-body feedback loop

✵ The List of You—identify old versus current self-labels

✵ The List of Your Nemesis—identify mirrors of your own negative traits

✵ Open Heart—release judgment, compassion

✵ Right Words—compassion

Voice and Speech

✵ Tune In—voice awareness

✵ Stressful or Soothing—voice impact

✵ Wet Dog Talking—voice-body connection

✵ Tone Talk—tone impact, tone control, tone choice

✵ Subtle Subtext—vocal emphasis, volume impact on meaning

✵ Subtle Text—audience awareness, vocabulary

✵ Hear Yourself—hear unconscious habits

✵ Lazy Lips Workout—enunciation

✵ Filler Be Gone!—reduce/eliminate “ums,” “you knows”

Shoulders/Posture

✵ Fan Arms—back strength, posture, open chest

✵ The Butterfly—posture, alignment

✵ Weighted Neck Stretch—relaxation, stretch

Breathing

✵ Belly Breath—abdominal breathing

✵ Corner Speak—volume control

✵ 10-Second Breath—relaxation, controlled breath

✵ Abdomen Vibrate—relaxation, vocal resonance

✵ Chest Vibrate—relaxation, vocal resonance

✵ Torso Vibrate—relaxation, vocal resonance

✵ Breath with Arm Thrust—energize, focus

✵ Get the Peanut Butter Off—energize, release stress

Arms

✵ Hand Rest—relaxed hand position

✵ Hand Dance—break habits, explore new hand and arm gestures

✵ Hand Watch—self-awareness

Mirror

✵ Body Scan—body tension

✵ Bag of Sand—relaxation