Play the Part: Master Body Signals to Connect and Communicate for Business Success - Gina Barnett (2015)

Part I. THE STORIES OUR BODIES TELL

Chapter 1. Use Your Head

“You can go a long way with bad legs and a good head.”

—GAVIN MCDONALD

I’ll never forget my second grade teacher, Miss Murphy, quizzing our class on how to greet a stranger. “What is the first thing you should do after you open the door?” she asked. Hands shot up.

“Yes, Billie?”

“Shake hands.”

“Good answer, but that’s not the first thing. Susan?”

“Say hello?”

“Another good answer, but that’s not the very first thing.”

Others offered ideas. All were sensible but not the answer she was looking for. Seven years old and we were stumped. Finally, Miss Murphy saved us from our befuddlement. “Smile,” she said.

I think about that second grade lesson quite often these days as I pose a variation of her question to my clients. Surprisingly, what I encounter isn’t wrong answers, but resistance to the correct one. It’s made me wonder just what it is about smiling that makes people so profoundly uncomfortable? Men think it weak or phony to smile; women worry it undermines the little power they’ve attained. I had one client go so far as to say, “I’ll have to work on perfecting a fake smile that looks genuine.” Perfect a fake smile? Really? Why not just smile and mean it? Why is there such resistance to joy, pleasure, or just sheer warmth?

No matter how many reasons people come up with for not smiling, I suspect the deepest reasons relate to the vulnerability of the mouth itself. When we part our lips, we reveal—and revealing is risky. Clients have told me over the years that to show emotion, or overtly feel, is perceived as weakness. To be open is to leave oneself open. Juniors in the workplace observe serious-minded seniors and determine that to succeed, one must look grim. Those in middle management tell themselves that smiling diminishes credibility and authority. No matter why people feel compelled to repress their warmth, the results are pretty universal: clenched jaws, mumbled words, dour expressions.

This chapter will focus on the head—in truth, an entire book could be written about the subject, as so much happens there! I’ll first explore the impact of physical attributes and choices, such as whether or not to smile. Then I’ll discuss the mouth, jaw, head-neck placement, eyes, and ears. The focus will then shift to internal processes, such as listening and point of view. This approach of separating physical aspects of the body from the internal, thinking, and metaphoric aspects is a completely false division. Why? Because there is a continuous body-emotion-thought feedback loop functioning in all of us all the time. By trying out the suggested exercises, my hope is that you’ll consciously experience this body-emotion-thought loop in action and discover the impact it has on both yourself and those around you.

![]()

Nancy Etcoff, a clinical instructor in psychology at Harvard Medical School and the author of Survival of the Prettiest: The Science of Beauty, said the image we project can influence our destiny. “Research shows there are a lot of advantages for people who are considered beautiful or attractive, everywhere from the boardroom to the bedroom… . The same is true for people who tend to make positive expressions… . And the act of smiling, even if it is forced, can be self-fulfilling in that it can on its own elevate the mood.” (Italics mine.) Why might this be? Simple: the impact of a smile is not just felt by the person doing it. Smiling is contagious, both on the faces and in the minds of its observers.

The smile, while a universal facial expression, has different meanings in different cultures. In the United States it signals friendliness and joy; in Korea smiling can be seen as representing shallowness. In other Asian cultures it can indicate confusion or distress. Whatever the particular cultural meaning assigned to smiling, the gesture itself is embedded in human communication. (In the United States, until Teddy Roosevelt, few presidents smiled in public settings.) While many in business consider smiling counterproductive to signaling authority, its absence creates other problems. The truth is, the body and emotions are not separate; they profoundly affect each other. As the psychologist William James wrote in 1892, “Thus the sovereign voluntary path to cheerfulness, if our spontaneous cheerfulness be lost, is to sit up cheerfully, to look around cheerfully, and to act and speak as if cheerfulness were already there.” We all know that when we’re happy, smiling comes effortlessly. What we need to learn is that the act of smiling itself can lift our and others’ moods. Whether or not the resistance to smiling is cultural, not smiling, with its attendant mouth and jaw tension, can engender feelings that are the antithesis of joy. We catch each other’s emotions quickly and without conscious awareness, and emotions are almost always made manifest in the face. I think my second grade teacher was on to something profound.

TRY THIS: HAPPY/SAD MOUTH

Put your lips in the position your mouth goes to when you feel sad. What happens? What do you feel internally just by moving your lips? Now tighten the lips and clench the jaw as you might when angry. What happens? Now smile just a little bit. What do you feel? Now smile broadly. Try a fake smile. Now think of someone you adore or a happy memory and let the mouth organically go where it feels right. Notice how quickly the mere thought affects the mouth position and how a mouth position triggers a subtle change of emotion. It’s my supreme pleasure to introduce you to the body-emotion two-way street! Welcome! We are just getting started.

What happens in those first moments when strangers meet? The handshake, facial expressivity, eye contact, vocal tone, head-neck alignment, and a multitude of other factors are instantaneously processed by the brain. As we size others up—is this stranger smart, trustworthy, confident, arrogant, warm?—they are doing the same with us. The signals sent are complex, instant, and powerful. As the saying goes, “You don’t have a second chance to make a first impression.”

Functional MRI technology now allows us to peer into the brain as processes occur. With the ability to probe into previously hidden aspects of brain function and activity, our understanding of smiling is deepening and is especially interesting when understood in light of mirror neurons. Currently, these neurons are understood to be a widely dispersed class of brain cells described by researchers as a kind of neural Wi-Fi. They were serendipitously discovered in the 1990s and are a special class of cells that fire when an individual merely observes someone performing an action, even though the observer isn’t doing that action. The implications of this are yet to be fully understood. We know that the rapid synchronization of people’s paces, gestures, and postures as they interact has long been observed. The result is a feeling of rapport and alignment. Then there is the concept of emotional contagion, in which one person literally catches the strongly expressed feelings and emotions of another. Imagine yourself coming into work feeling OK but running into the chronic complainer. You chat briefly, and as you walk away, you find yourself feeling irritated and no longer OK. Sound familiar? That’s emotional contagion. This too may soon come to be understood in light of this neural brain-to-brain Wi-Fi of mirror neurons.

This merging of separate bodies into a connected circuit has been defined by the psychologists Lisa M. Diamond and Lisa G. Aspinwall as “a mutually regulating psychobiological unit.” (Just think of how contagious yawning is. I’ve even caught the “yawns” from my dog!) We’re beginning to understand how the biology of one person can affect and even change the biology of another. If merely observing an action activates the same brain areas as that of the person performing the action, then this extremely rapid brain-to-brain mirroring will cause physiological effects in both people. Think of a stressful business meeting and recall how quickly strongly expressed emotions provoke equally strong emotions in others. Almost instantly, all around the room, heart rates jump, breathing shallows, and palms sweat. One person’s hostile remarks can trigger another’s blood pressure to spike. How can this be? Because we are not alone in these bodies. We are social beings bound together in systems of continuously mutually regulating interactions. The social script that we write together is impacted by all our bodies as they express themselves physically, but also as our brains mentally reenact what we witness. Perhaps by enabling us to “catch” each other’s emotions, mirror neurons will be revealed as the source of empathy. Whatever their cause or source, the next time you catch yourself refusing to smile because of how it may make you “appear,” remember that by allowing yourself to smile, you very likely may be creating an invisible smile in the minds of your observers. Your warm smile might also calm another’s anxiety. Wouldn’t that be a great way to initiate a successful connection?

THE MOUTH

The mouth is an emotional center of enormous power. Many steps in the progression from infancy to toddlerhood are marked via the mouth. The mouth is where the first bond between infant and mother is created. As the months go by, babies explore objects with their mouths well before they refine the use of their hands. Infants’ mouths will frequently twist into grimaces of despair well before you hear their first wails. Smiling occurs at around eight weeks of age and, irrespective of culture, is a much anticipated benchmark of development. It is also well rewarded with jubilantly returned smiles from parents. Early babbling is happily encouraged, as is drinking from a bottle and eventually eating with a spoon. Feeding oneself is a milestone of achievement. Each of these stages of growth is navigated via the mouth, and all occur before speech even enters the picture!

As adults, beyond dental care and grooming, few of us give much consideration to our mouths. But how lips move, jaws release, and tongues create sounds are all vital aspects of communication. (A number of excellent books are available on the voice, vocal production, speech, and accent reduction, which I’ve listed in Appendix C, so I won’t go into too much detail here regarding that aspect of the mouth and its role in speech.) I’ll focus on the critical, micro-emotional messages the mouth sends, as these are powerful indicators of a person’s inner emotional life.

What I encounter most frequently in the business world, where clear communication is essential, is minor lockjaw. People—whether it is because they are in a rush to express their thoughts, hide the feeling behind their words, or unconsciously wish not to be heard—open their mouths the smallest possible amount in order to speak. The result: rushed, mumbling speech is difficult to engage with or even understand. Jaw tension may be the result of something physical, but often it’s rooted in something emotional. The most extreme example of self-muzzling I encountered was with a client in global banking. She was a brilliant analyst with a specialty in regulatory affairs, but she was almost impossible to hear because she literally ate her own voice. Her jaw hardly opened when she spoke; she projected her sound backward into her throat rather than out into the air. Her volume was low and her enunciation fuzzy from lack of movement. I put my hands on the muscles beside the jaw hinge and urged her to relax and let her mouth hang open. The tears were instantaneous. As a child she’d been molested by a neighbor who told her he’d kill her if she ever spoke of it. She never had. Instead she cut off her own voice. This deep trauma lived on in the story her body was telling. Granted, this was a very extreme case. Nonetheless, when growing up, who of us was never told to shut up? Many were told that repeatedly. How each body managed that instruction is unique. For some, it was of absolutely no consequence; for others, it resulted in lifelong self-silencing.

Much of our physical life is on automatic pilot. Systems and habits are laid down early in our development. Most of us pay little to no attention to our bodies as we move through our workday. Granted, pain will slow us down or stop us, awaken us to our physical self. Otherwise, we rarely take the time to tune in to the richness that is contained in our physical being. We should. Our bodies house our histories, our reactions to events and our current and past emotions. Many physical responses are conditioned by factors about which we have limited or no conscious recall. (We’ll explore that more deeply in Chapter 3 on the gut.)

The mouth vividly manifests our feelings: joy, rage, disgust, sadness, fear. We can’t read each other’s thoughts, but we can become far more attuned to others’ feelings by observing faces in general and mouths in particular. Recall for a moment how quickly your feelings changed by making subtle lip and mouth movements in the exercise “Happy/Sad Mouth.” The irony about frozen or locked jaws, if one looks beneath the surface to the subtextual signals being sent, is that they can reveal as much as they seek to conceal.

TRY THIS: SWEET APRICOT: JAW RELAX

Observe if your upper and lower teeth are touching or pressing together when your mouth is shut. If so, a good way to approach relaxing the jaw is to imagine you have half a fresh apricot resting on the tongue. This will help you drop the tongue and release the pressure between the teeth, which should not be pressed together. This position, coupled with imagining the apricot, will gently relax the muscles that tend to clench the jaw.

Why do this? To consciously attune yourself to those muscles and to notice if you have chronic jaw tension. Do you grind your teeth? If you do, ask yourself, is this preventing my ability to enunciate, to be heard and understood? After relaxing your mouth, gently rub the muscles at the jawline in a circular motion to deepen the relaxation.

HEAD-NECK ALIGNMENT

Jaw tension is not a singular event and is often the result of how the head sits on the neck. With many of us now spending almost all day at our computers, often after long commutes by car or train, there’s an epidemic of what I call “head thrust.” The upper back is curved in on itself, and the head lurches so far forward that it’s several inches in front of the chest and sticks out like that of a turtle. Proper placement of the head upon the neck has great impact not only on the voice but on how one appears and is thus perceived, and even more critically on how one feels.

The head weighs approximately 10 pounds, not all that much. Imagine holding a 10-pound weight in your hand with that hand held straight up in the air. By holding the hand perfectly upright in that position, the wrist, elbow, and shoulder all the way down to the hips and feet will enable you to support the weight. Now imagine moving that 10-pound weight forward by just a few inches. The effort required to hold those 10 pounds will be dramatically different; the muscles will have to work much, much harder to hold the weight in place. It’s the same with the head. A head that juts far forward of where it is structurally designed to sit demands extensive and exhausting muscle work to hold it there. Over time those muscles wind up shifting the inner skeletal structure itself.

One of the first places our eyes go for information about someone is that person’s head-neck alignment. We can see immediately if a head is “held high,” tucked in on itself, or weakly supported with poor posture. On the most superficial level, a head that sits properly on the neck—is flexible, supported, and aligned—immediately sends messages of strength, health, and energy. How does it do this? It takes strength to support the head correctly. It takes energy to maintain good alignment and posture. Correcting improper head-neck alignment is a process that requires effort. Just telling yourself to sit up straight will not correct 10 to 20 years of incorrect alignment, although reminding oneself to do so is a good first step.

Keep in mind that the body is structurally built at the skeletal level for posture that enables maximal motion and flexibility. Awareness that proper alignment is vital for signaling presence, power, and confidence can make it easier to start making small changes. I had a client who was quite tall and had severe head thrust. His head was literally about three inches in front of his body. When I pointed it out and suggested he work to correct his head-neck alignment, he responded, “I’ve always been like this. It’s the way I’m built.” I told him my concern was that his posture made him look as if he were “asking” rather than “telling.” “It’s not the look of a leader,” I said. Ambition won out, and after “always been,” he quickly shifted to “better become,” and within weeks he corrected his posture.

Another client, who was being groomed for a C-suite position, was sent to me because, despite his intelligence, he was not perceived as a leader. His head was tilted to the left, with his left shoulder raised toward his left ear. This head tilt shortened the muscles along the left side of his neck and shoulder, sending subtextual signals that could be perceived in a number of counterproductive ways. Despite his intelligence, he looked crumpled and unsure, doubtful of himself and others. His seniors were concerned that if he had to announce grave decisions while appearing so unsure, it could have negative outcomes.

Another client, EVP of a significant financial institution who was being groomed for advancement, had poor posture that resulted in his tendency to tuck in his chin. This had numerous consequences: a mumbling vocal tone, a flat vocal melody, a stern countenance from peering up from under his eyebrows. These factors combined to send a complex set of signals: the flattened tone made him seem dull and tired; the countenance made him appear irritated and impatient; the rounded shoulders made him seem unfit for greater leadership. This physical stature made him appear anything but “presidential.” He responded to my suggestions for improving his head placement and posture by saying, “I’ve seen a lot of empty suits in my day who look the part but have nothing of substance to deliver.” I replied that empty suits certainly exist, but my concern was that the persona he projected was not commensurate with the role being played.

I mention these three clients because as a communications coach, I never seek to impose choices that result in inauthentic or fake behaviors. My goal is to help the client get rid of counterproductive, unconscious physical habits that obscure the full potential of his or her power and expressivity. As people move up professionally, they often have to adjust their physical habits to more appropriately embody new roles. While people completely understand and accept this as it concerns professional attire, they rarely think about how it concerns head placement! But it is precisely because we make such instantaneous decisions about one another that counterproductive postures can have long-term implications.

Social psychologist Marshall McLuhan said, “The medium is the message.” The form of delivery is as significant as the content being delivered. (Twitter anyone?) As a communicator, you are the medium; your body is the medium through which your content is delivered. For this reason alone, it is essential to have alignment of body and message.

As with smiling, proper or poor head-neck alignment will impact our and others’ feelings and emotions. I’ve encountered similar resistance to it. Some statements were downright stunning: “Standing up straight is arrogant and pompous.” To the contrary, authority, alertness, gravitas, intelligence—all are signaled by a well-aligned head-neck relationship. “It’s tiring.” Also untrue. Proper alignment, while not necessarily requiring less muscle recruitment, requires less effort. “It’s unnatural.” Bah! One of my all-time favorites: “So, all I have to do is stand up straight and people will think I’m an expert?” If only life could be so simple! Such arguments mask the deep resistance to the physical and mental work required to fight not only gravity but inertia and a lifetime of bad habits.

Change is hard. Habits are ingrained. Resistance is often the first thing I encounter when I make a suggestion. “Yes but” is a phrase I’ve heard countless times. When I was a child, teachers often said, “There’s no such word as can’t.” As a coach, I often hear myself asking, “You can’t or you won’t? There’s a difference.” Resistance is normal. It’s everywhere. (Friction is resistance!) Reflection, or taking the time to consider why we resist change, is an important first step, but things mustn’t stop there. We have to actively engage with our reluctance to make change, to question if the resistance is well founded and purposeful or if it stems from laziness or, most critical, fear. In my experience, most people who really push back and resist incorporating suggestions for improvement are afraid. It’s like being in a roaring river and holding onto a rock for dear life. If you hold on, you’ll die; if you let go, you’ll be swept away. Either choice is terrifying. But letting go just may allow the currents to carry you to safety. Or not. It is impossible to know. The only certainty is that holding on will keep you stuck. We cling to the known precisely because it is known. What change will usher in is unknowable, so we resist it. Only when familiar habits become obstacles to success do we begin to welcome change. Fear of failure supersedes fear of the unknown, and resistance begins to give way to curiosity and openness. My question is, why wait? When resistance rears its head, ask yourself, “What am I afraid of? What will happen if I let go and allow the current of change to carry me somewhere unknown?”

TRY THIS: HEAD HINGE

Let’s play with head position. Imagine you are in a meeting. Tilt your head down and look up from underneath your eyebrows. Hold that position for 30 seconds. What do you feel? What do you imagine others might see? Now do the opposite. Lift the chin up by two inches and look “down your nose.” Notice how the back of the neck shortens? Hold that for 30 seconds. What do you feel? These are extremes, but they give a good idea of how much subtext could be projected through such a position. Something as simple as attaining a level chin position can have a big impact.

TRY THIS: BROKEN BRIDGE

As you sit with this book in your hands, begin to slump. Let the head droop, the shoulders curl forward, and the belly collapse. Put your lips in a downward, sad expression. Sit like that for 30 seconds and notice how you begin to feel. Sad? Bored? Tired? Just plain blah? By experimenting with these positions, you can immediately experience how the physical positions impact emotions. Play with varied facial expressions to see what subtle emotions emerge.

We all know that when we feel sad, the body responds and looks sad. The above exercises are another way to consciously experience how posture impacts emotion. Furthermore, if you stayed in the slumped position described above for any period of time, not only you but those around you would begin to feel depleted of energy. Mirror neurons show us that contagion has physical as well as emotional ramifications.

There are multiple ways to address chronic head-neck misalignment, but what is most crucial is the willingness to do so. Unlike breathing, which we do automatically—but often incorrectly, more on that later—posture requires attention. To maintain proper alignment of the head, the core muscles of the abdomen must be employed. Good posture does not happen in the shoulders, but in the deep core muscles of the belly and back, where the innermost muscles surrounding the middle and lower spine engage. Sometimes, to correct decades of misuse, it is essential to work with a professional who understands the body, who can analyze your particular patterns and determine what muscle recruitment and strengthening exercises are necessary. That professional, be it physical therapist, Pilates instructor, or Alexander Technique teacher, can then give you daily exercises that target the necessary muscles to get the spine back to where it should be. In time, what was an enormous effort becomes second nature as the body self-corrects. Whichever route you take, what is most critical—as in all other aspects of change—is repeated practice. The good news is that brief repetition of corrective exercises, performed daily or every other day, can make a real difference rather quickly.

What is fascinating about the mind-body relationship is the increasing understanding of how even imagining a physical act can impact new—correct— muscle recruitment. If, for example, I suggest that you imagine an umbrella, your mind’s eye will create that image. Picture a snake. Now a tulip. Visual imagery engages the part of the brain where things you have seen with your eyes have been stored as pictorial memories. But there is kinesthetic imagery stored in the brain as well. Imagine yourself swimming. Now imagine running or pouring a cup of coffee. As you imagine these movements, your brain is performing the movement.

One theory for this is that the brain must emulate movement before it is actually performed. Imagine how effortlessly we pick up a glass. The hand knows exactly how far to go. Imagine going into your pitch-black bedroom. Your hand knows precisely where the light switch is. Conversely, imagine entering an unfamiliar location and randomly patting the wall, searching for the switch! We predict, and the brain does so beforehand as a way to navigate our constantly changing and complex environment. Over the years I’ve observed numerous musicians on the bus or subway in New York City mentally rehearsing for a concert. Without moving a finger, they mentally “play” through a piece. Studies have shown that this form of rehearsal has profound benefits. Similarly, once you have begun to master proper head-neck placement, merely imagining the body in the correct position can have great benefit. When a physical action is mentally rehearsed, it actually changes the brain’s motor map and the body follows along.

The take-away from the above exercises is not merely that slumping impacts appearance and shifts emotion and energy, but that good posture radiates strength, engenders energy, and actually makes you feel better. This is not to say that everyone needs to look the same to manifest energy and presence. I’ve worked with amazing individuals who are wheelchair-bound or have severe scoliosis or other postural handicaps. Despite any handicap, one can still project confidence and conviction through many other means of communication—voice, eyes, facial expression, gestures—which we will also explore. Nonetheless, whether we like to admit it or not, we all make rapid judgments about people’s credibility, trustworthiness, and reliability based on very subtle cues that are instinctively assessed. It is far better to attempt mastery over head-neck alignment, posture, and the emotional and physical signals sent than not.

The first thing we instinctively do when we feel or are threatened is to pull our neck back, hunch our shoulders, and cower. The stresses of the modern day, while not akin to those of hundreds of thousands of years ago, still trigger the same autonomic responses. The amygdala, a primitive brain structure within the limbic system that’s deeply involved with survival, emotions, and memory, doesn’t know the difference between a leaping lion and a dirty look from a colleague. Either will set off the survival alarm, boost cortisol (the stress hormone) levels in the brain, and trigger the fight, flight, or freeze response. Recent studies by Amy Cuddy, professor and researcher at Harvard Business School, explore the connection between posture and stress response. Cuddy discovered that consciously putting the body in what she terms a “power position”—in which the body claims and occupies space with an erect posture, either arms spread wide or hands behind the head and elbows out to the sides—and holding that position for two minutes changes the chemical balance in the bloodstream. Holding a power position for as little as two minutes lowers cortisol and increases testosterone (the courage hormone), hormonal changes that can affect thinking and behavior.

Before you head into a stress-inducing conversation or presentation, try holding a power position for two minutes, take a few deep breaths, and see how you can both boost your confidence and calm yourself down.

THE VOICE

The voice exits the body through the mouth, but its source is the breath. The structure and shape of the body create resonance and timbre. I will cover the voice as it works its way through various centers of the body subsequently and in much greater depth in Chapter 2, but as far as posture is concerned, a strong head-neck relationship is essential for a relaxed, open sound. One result of head thrust is vocal fry. Jutting the head forward puts strain on the throat and on the vocal cords; the sound that emerges is hoarse, thin, dry, and crackly. Over the long term, inflamed cords or even nodes can result. At a recent presentation I attended, a speaker had severe vocal fry. About 20 seconds into her presentation, people all around the room began clearing their throats. Why? Her fry made them aware of their own throats, and unconsciously they were signaling for her to clear hers. Or quite possibly it was those mirror neurons again.

TRY THIS: WET DOG

Shake out your body for a few seconds, like a dog shaking water off its coat. Do a few shoulder rolls and gentle head rolls. Yawn a few times to open the throat. Take a nice deep breath and stick out the tongue and speak, with the tongue extended far out of the mouth. Do this for a minute or so. Relax and now speak normally. Do you notice a change in how the voice resonates? Is it more open and relaxed sounding?

The goal for the voice is to suit the intention of the communication. A voice should be easy to hear and understand as well as pleasant to listen to. The best way to achieve a relaxed, open, pleasant voice is to have a relaxed body. Almost all vocal challenges are the result of tension that is located somewhere along the route of vocal production. Tension, whether in the belly, chest, throat, jaw, or mouth, will impact the voice overall. But since this chapter focuses on the head, what’s most critical is to be aware of how something as minor as an upturned chin or a clenched jaw can impinge on the resonance, volume, and enunciation of the voice and speech.

TRY THIS: HEAD HINGE WITH VOICE

Repeat the “Head Hinge” exercise, raising the chin a few inches, and this time recite your name, address, and phone number with your head held in that upward position. What happens in the throat? How does the voice change? Now drop the chin a few inches, lowering the head, and again recite your name, address, and phone number. What do you notice about the sound of your voice by playing with the position of the head? Now come to a level position. Yawn, stick the tongue out, and speak your name and address with your tongue out. And finally, keeping a level head with the jaw relaxed and tongue in a normal position, speak again. What do you notice?

TRY THIS: REVERSE TURTLE NECK

If from doing the above exercise you discovered that you generally keep either your position tilted or your head thrust forward, there is a very simple remedy for proper head placement. This exercise awakens, lengthens, and strengthens the often underutilized muscles at the back of the neck. Make sure that your head is level and tilted neither up nor down. (The best way to do this is by looking straight ahead and into a mirror. We often cannot feel a habit of head tilt up or down.) Place two fingers on your chin and very gently press the chin back toward the spine. The head might move just a half inch or so, but you’ll feel the muscles in the back of your neck engage. The tendons and muscles at the front of the neck should not engage at all. Hold for 10 seconds and release. This can also be done without the fingers. While standing in an elevator or at a red light, make sure the head is level and gently bring the chin back and hold for 5 to 10 seconds. (If you do this with the head tilted slightly upward, then it will actually be counterproductive and increase the shortening of the muscles at the back of the neck. That’s exactly what this exercise is designed to prevent.) If repeated throughout the day, in time, you will begin to hold your head without jutting it too far forward on the neck. Again, be extra careful to make sure that your head is level when doing this.

EYES

The eyes are powerful. Eye contact is essential. Guarded eyes, welcoming eyes, bored, tired, shifty, cruel—much is communicated via these two glassy orbs. Actually, a lot of eye signaling is accomplished by the tiny muscles surrounding the eyes that allow us to squint, smile, and frown. It’s said that should the muscles around the eyes not engage when smiling, the smile will be perceived as cursory instead of heartfelt.

The eyes send and receive simultaneously. But what precisely do they send? The signals that emanate from the eyes are powerful indications of one’s security, intelligence, warmth, openness, humor, strength, and leadership. Conscious control of one’s eye use can best be understood by watching great film actors in close-up, and I highly recommend renting films with exceptional actors to study how they use their eyes and the muscles that surround their eyes to communicate specific messages. (Dustin Hoffman and Meryl Streep come to mind as two masters of extraordinarily subtle eye expressivity.)

Never forget that how eyes communicate is as much culturally as personally determined. I work with a number of men from the Middle East who do not make eye contact with women. It is culturally against their upbringing. I’ve had male clients tell me that locking eyes, a technique used in active listening for effective Q&A, is impossible because they’ll be perceived as sexual or flirtatious. Clients from India have taught me that direct and sustained eye contact with an elder is considered disrespectful. The question is, now that our world is so globally connected, how do we manage these cultural differences? The first is to become educated about them, so that, for example, if someone refuses to make eye contact, you can determine whether or not it is due to his or her culture. The second is not to impose your cultural bias outward, but to be respectful and patient with the signals you receive. This can be challenging, but it is worth its weight in gold for building trust.

In our increasingly global world and given that eye contact is viewed very differently by various cultures, it is vital to familiarize yourself with the traditions of the people with whom you may be working. Everyone has to be flexible, to bend a bit around the extremes of cultural behaviors. But keep in mind, other people are coming from their own “unconscious” muscle memory and may not be able to “feel” in their muscles how their eyes are communicating. It is equally important not to project your values onto someone from another culture for whom direct eye contact may be considered rude or disrespectful. Find out as best as you can the traditions of someone from a foreign culture before “interpreting” his or her body language from your frame of reference. Keep an open mind and listen not merely to the eyes, words, and face, but take in the entire being as he or she communicates. We send an infinity of messages in a multitude of ways far beyond the most obvious. It takes time and attention to be able to read people to the best of our ability. And even then, at best, we are mostly guessing! Nonetheless, I have found that by not imposing any imperative for eye contact and just being patient, in time even the most reluctant, guarded eye contact seems to fade away, irrespective of culture or gender.

The greater challenge for those who tend not to make eye contact is that they miss seeing the microsignals coming their way. When eyes are focused down, up, or away for long periods of time, they can’t capture what’s visually being expressed toward them. To miss those signals can have serious results. Whether driven by culture or habit, it’s important to understand the impact that not making eye contact can have on any encounter and work toward finding a happy medium.

To make sufficient eye contact, however, doesn’t mean to stare. Eye contact that’s maintained 60 to 70 percent of the time is sufficient to signal your presence and attention. Also, we’ve all sat in meetings where the person in charge focuses exclusively on one or two people, thereby making those excluded from eye contact feel “lesser.” (Never forget: today’s junior may be tomorrow’s president. Honor everyone.)

TRY THIS: STAR EYES

Rent a movie and, with the sound turned off, watch to see if you can guess the emotional content from the actors’ eyes. You’ll note quick and constant changes in the muscles around the eyes.

The length of eye contact, smiling with the eyes to signal agreement, quick darting eye movements from side to side—there are an infinite number of signals that the eyes send, and if they are not within your conscious control, there can be serious consequences. One client who was being groomed for a promotion had the habit of darting his eyes quickly to the left while he framed answers to questions. It was an unconscious habit with no overt intention, but the effect on his observers was profound. This rapid, habitual, unconscious movement made him appear unsure and, to some, untrustworthy. This couldn’t have been farther from the truth! He was an entirely capable, honest, and completely above-board fellow, but this unconscious habit was a serious hindrance to his success. When I pointed it out, he had no idea what I was talking about. He literally could not even feel it. When he saw himself on video, he was shocked.

“It’s so obvious. I can’t believe I do that, and I had no idea. I look so shifty-eyed.” We worked on it by having him do the shifting movement on purpose. We slowly broke down the gesture into tiny increments so that he could consciously feel and isolate the muscles at the very beginning of the movement. Only by forcing himself to “consciously” shift his eyes could he train his brain to recognize the feeling and break the habit.

While it seems counterintuitive, I’ve found this approach of slowly and intentionally repeating a habitual, unconscious, potentially derailing gesture so that it can be consciously “felt” to be quite successful. I’ve used it with chronic eyebrow raisers, those who carry a lot of brow tension, as well as stomach and shoulder grippers. When muscles move in certain ways for decades, they literally become stuck in patterns that can no longer be sensed and the brain seems unable to recognize. They become automatic. (The more any gesture is repeated, the deeper the neural paths associated with it.) But by applying slow-motion movement with focused awareness, these habits can be identified and broken.

TRY THIS: JUST AN INCH!

For a simple way to experience just how profoundly muscle memory is embedded in the body, try walking with your feet turned in or out just and inch, or shorten or lengthen your gait by just a few inches. It will feel massively different. That’s how powerful muscle memory is.

TRY THIS: HABIT BREAKER

If you become aware of any unconscious physical habit, break it down into its microelements, very slowly repeating them with conscious focus and intention. This will allow the brain to register it and begin to catch it before it catches you. This is not something to be done merely once or twice, but repeatedly over time, sometimes for weeks or months. For old habits to be broken and new ones to be created takes tremendous focus and attention.

TRY THIS: MIRROR TALK

Watch yourself in the mirror while talking on the phone. Observe how the head sits on the neck, what the mouth does, and how muscles around the eyes move as you talk about various subjects. Observe how the intention of the communication succeeds or is hindered by any habitual muscular movement. Once conscious of any habitual derailers, you can begin to address them through the repetition exercise suggested above. For even more information, video-record your face while communicating.

FACE NEUTRAL

Somewhere between a blank stare and an easily readable expression sits face neutral. Relaxed, open, listening, face neutral does not reveal your emotional response. It is present but not judgmental, acute but not worried. It is accomplished by relaxing the muscles from brow to jaw, keeping the lips closed but not pressed together. Why have this expression at your disposal? Several reasons. There are times when it is essential to signal our emotional response with our faces, and there are times when, for a myriad of reasons, it’s counterproductive to reveal our emotions. Managers, teachers, or even parents, as they listen to two sides of a story, should attempt to be open to both sides. Practicing a neutral facial expression will not signal bias as you listen, and thus it will not reveal your emotions and reactions to the speaker. During negotiations, employing face neutral is often essential. (Teenagers are masters of face neutral when they don’t want their parents to know something is up!)

EARS

Listening is my personal obsession (and passion) because I encounter very few people who truly embrace and understand what listening asks of us. Listening is an art that requires training. Unfortunately, despite the fact that how we listen affects everything we do, there is no curriculum designed to teach listening. How we listen has a direct result on what we hear, and what we hear often has an immediate impact on how we react. Our reactions then set up other reactions, often in microseconds, and before we know it, an emotional avalanche is under way.

Listening requires muscle, stillness, calm, and … wisdom. There are also many levels to listening and to listening with openness. There is literal listening to the sounds around you, with conscious attention. Most of us tune out the myriad of sounds that occur moment by moment, but a good way to begin to address active, or empathic, listening is not to tune out sounds but to become so still as to really absorb them.

TRY THIS: ELEPHANT EARS

Sit in a chair, close your eyes, follow your breath for a few moments, and then tune into sound. First pay attention to the sounds that are immediately around you: your breath, a clock ticking, the radiator hissing. Then expand your consciousness to the sounds immediately outside the room you are in. Keep expanding down the hall, outside the building, in nature—just keep expanding your listening so that your entire body becomes an enormous ear. You’ll be amazed at how both relaxing and energizing this small exercise can be. Rather than shutting out sound, you begin to seek it out eagerly, and it is always full of rich surprises.

Even on the purely physical level, listening is a delicious moment-to-moment encounter with the world around us. As noise levels increase everywhere, we routinely try to shut out sound or plug our ears with headphones. Unless you’re in an environment that is painfully noisy, actively listening to the richness of sound is a delight in its own right. Tuning in rather than tuning out is fascinating. I once knew a drummer who rode the subway just to listen to the varying rhythms created by the tracks. So much of what we try to avoid, if we merely relax and let it in, reduces stress enormously.

This exercise is both a pleasure and a warm-up to a deeper kind of listening. After practicing this level of listening to the “outer” stimuli, begin to focus inward and listen to yourself. The first muscle required to enable active and open listening to others is the ability to hear oneself, to step away from one’s thinking process or the endless loops of inner noise that consume vast amounts of our mental energy.

INSIDE THE HEAD: LISTENING INSIDE AND RESPONDING OUT

Many of us don’t think; we obsess or ruminate. We have repeated conversations with those who are not present, either rehearsing some future encounter, replaying a past one, or rewriting one already experienced. We spend vast amounts of time locked inside our heads with little conscious connection to the moment in which we are actually living. But how we think has a direct impact on how we behave and who we become. The Dhammapada Sutrafamously says, “We are what we think.” Many meditation practices are designed as a way to step beyond that constant inner noise to the deeper, quieter self. That deeper self has been given many names: the third eye, the watcher, true being, Buddha Nature. It is essentially that part of isness that is beyond the chronic, habitual, busy, thinking mind most of us occupy most of the time. It is a place of stillness and involved detachment. By listening hard to our own thinking process, we begin to discover that aspect of being that isn’t “attached” to endless loops of obsession. We can actually begin to hear our own nonsense, how passionately involved it is with either defending ourselves, judging others or ourselves, critiquing, or assessing. We are all geniuses of righteousness or masterminds of self-loathing. What we aren’t are skilled observers of ourselves.

Listening to our thoughts and then watching them go by is the first step toward connecting with that part of the self that goes beyond the ego’s need to be right, or better, or the best. We can enter a place of stillness and calm that offers perspective and even relief. This is not to say that all thinking is bad or wasteful. Thinking is an excellent tool when it is applied to solving problems, managing complexity, creating alternatives. But that kind of focused thinking is the opposite of the endless, ruminating mind chatter that obliterates our ability to be fully here in the now. Why is this important for communication? Because it’s impossible to connect when we’re stuck in our own heads and not tuned into the moment.

TRY THIS: INNER EAR

After doing the “Elephant Ears” exercise for a few minutes, shift your attention to what is happening inside your head. First listen to sound and then listen to your thoughts. By doing so, you can begin to develop an inner ear that hears thoughts beyond the most obvious, the equivalent of the silence between the notes in music. Most meditation is about “letting go” of thoughts, and that is a great practice. But there is great value as well in actively listening to the constant inner chatter. Themes that run as a quiet constant inside the mind can be observed. Do they have value? Are they aligned with the actual present, or are they vestigial habits, old voices? The simple truth is, if you don’t hear them, you can’t modify them.

At work, those more adept at quieting the inner chatter have an easier time really hearing others. Often when listening we’re (a) waiting for the speaker to get to the point, (b) judging, (c) criticizing, (d) assessing, (e) deciding if we agree or not, (f) planning our rebuttal, (g) processing how to respond. Sound familiar? Very few people merely listen. Encountering those who manage to shut off their own inner tapes and truly enter a place of pure listening is wonderful and inspiring. Their power and effectiveness are often a direct result of their listening style. Also those who feel deeply heard, even when there are conflicting points of view in response to their ideas, are far more open to navigating those conflicting responses. Being heard creates a powerful bond. Bonds build trust; trust builds relationships; relationships build business. It all starts with and hinges on deep listening.

There are also concrete ways, once one shuts off the inner tapes and truly listens, to signal that one is fully present. Eye contact, as mentioned earlier, allows you as a listener to receive microsignals. The best way to listen is to completely stop what you are doing. Put down that smartphone or close that spreadsheet and turn to face the speaker. Using your upper torso, not just your head, face the person and look in his or her eyes. While the person is speaking, quiet your thoughts and listen not just to the words and tone but to the whole body—the gestures, posture, and facial expressions. Listen as well to that which is not said but is expressed emotionally. As you listen, signal to the speaker that you hear him or her by occasionally nodding and smiling. You can nod even if you disagree with the content, because nodding doesn’t signal accord, merely understanding and presence. (Beware of too much nodding, however, as that can send a signal that you are overly in agreement when that may not be the case. Additionally, too much nodding can actually impact your own decision making. If working globally, familiarize yourself with the different cultural meanings of nodding. For example, in India nodding means I hear you, not I agree with you.)

These are such basic rules of engagement that it’s amazing to me how often people forget them. There are so many things pulling on our attention, competing for our time, that we forget the power of simply stopping and listening.

Responding after listening is another skill that requires stillness. Many clients have said, “But if I take time to actually think about my response, I’ll be perceived as ignorant, weak, or unsure.” This is a symptom of how communication has been affected by lightning-speed technology. Thinking is not a sign of stupidity or weakness! It’s exactly the opposite. Taking the time to frame, shape, and think through a response indicates not only security but the ability to weigh alternatives.

If, when listening, you give your full attention both physically and mentally to the speaker, if you quiet your busy mind and become as empty as possible, you can more easily access a part of yourself that is beyond the immediacy of the situation at hand. You can actually tap into wisdom as opposed to mere information or defensiveness. I can imagine the multitudes of heads shaking. Who needs wisdom when the boss wants to know the numbers for the third-quarter bottom line! Practical nuts-and-bolts answers, when asked for, are one thing. But sometimes the kinds of questions posed in complex communication are far less cut and dried. They are open-ended and require thought. When we rush to answer as a way to demonstrate how “on top if it” we are, we often reveal the exact opposite. Remember, a question can be asked for a multitude of reasons—for the information the seeker doesn’t have, for your opinion, as a test, to poke holes in your argument—to name just a few. By really hearing the question, and what lies underneath, you can answer from a much more intelligent place. If you just jump in without thought, you can miss addressing the deeper question. Whether the question comes from a peer, client, or boss, at root, most questions are, “Can you solve my problem?” “How?” “By when?” “Why not?” At the bottom of what may appear to be aggressive digging for answers is often anxiety. The questioner needs your answer, hopes it’s right, fears you may not know it either. When responding from a place of calm listening, you are supplying not only the contextual answer the person may want but also the subtextual need he or she feels.

When what you have said is challenged or triggers actual aggression, the tendency is to defend. Listening stops, and points are lobbed back and forth with increasing intensity. A better practice is to respond to aggressive questions with curiosity. When someone overtly disagrees, take a breath and ask the person to explain in a bit more detail what the reservations are. Really listen to what is provided. As it becomes clearer why he or she may disagree, try, without getting defensive, to take in the new information being offered. To make sure you really understand, use the person’s precise words as you repeat the core difference or challenge that’s been expressed. Then don’t stop there; keep drilling down. “So, if I understand you correctly, you think this idea cannot work because … ?” Curiosity, along with drilling down and reflecting back, can defuse problematic exchanges and even create new solutions. But you’ve got to really listen.

POINT OF VIEW

“It is hard to fight an enemy who has outposts in your head.”

—SALLY KEMPTON

I worked with a senior vice president at a multinational corporation who suffered from stage fright. Her fear of presenting was so crippling that she actually scheduled vacations to coincide with major town hall presentations. Days before a presentation, she’d be unable to sleep; hours before, she’d begin to sweat, shake, and then become so dry in the mouth that she could hardly speak. As we worked together, I asked her to tell me what she imagined audiences think about her. In a blink she replied, “That I’m not good enough. That I don’t deserve this position.” This was her belief, despite her success and her having been in her current position for some time.

The other belief she had was that mistakes are failures.

When I suggested that mistakes are quite human, everyone makes them, they’re often not the end of the world, and quite frequently they can be portals to discovery, she looked at me like I was completely insane. Our “belief” systems were in direct opposition. What my comment permitted her to consider, however, was that this belief was merely that, a belief, not the truth.

What happens with these kinds of beliefs is that once we become convinced of them, we experience them as true. Then they can become self-fulfilling prophesies. By consciously exploring deeply ingrained beliefs that impact our emotional reaction system—and our bodies—we can begin to craft different patterns of thought and emotional response. This is not merely shifting the glass from half empty to half full, or the power of positive thinking, but consciously exploring the deep habitual ways we signal and send messages to ourselves, thereby creating certain patterns and outcomes. By consciously shifting those signals, we can create profoundly different outcomes and impact.

In theater, the term point of view is used instead of belief. But it’s very similar. If two actors are rehearsing the balcony scene from Romeo and Juliet, they learn the lines, the movement, and blocking (where they will move on stage). They decide on the actions they’ll play in order to fulfill their objectives. Romeo’s objective is to get Juliet to fall in love with him, despite the history of the family feud. His actions might be to woo, or to convince, or to impress. To make an actor’s choice more intricate or subtle, a director might say to Romeo, “OK, it’s coming along. This time I’d like you to do it with the point of view, or inner secret or belief: ‘I never get what I want.’”

That choice, that subtle inner belief, will totally color how Romeo plays the scene. It will, in theater terms, “read.” Likewise, if the director gives the actor the note, “Try it this time and play with the point of view ‘I’m irresistible,’” imagine the difference. Suddenly, the actor will have an entirely new air about him, cocky, sure, sexy, arrogant. It’s difficult to predict, but the only certainty is that the inner thought will have a profound effect on the signals sent, on the body that sends them, and upon the receiver.

Why is that? Point of view is powerful. When an actor shifts his point of view from “I never get what I want” to “I’m irresistible,” the effect on his carriage, movements, facial expression, voice, pace, confidence, attractiveness—to name just a few—shifts dramatically. Point of view is not merely playing with opposites, but exploring and having fun with nuance. For one actor, that point of view might open up a whole new vein of impulses and ideas. For another, it might go nowhere. Part of the game and joy of playing with point of view comes from the unpredictable and unintended results.

Going into a meeting you’re dreading? A job interview that puts your stomach in a knot? You can think over and over, “I’m so dreading this. I never know what to say,” or instead flip your point of view. Try “I’m going to be the best possible candidate.” “I can’t wait to see whom I might meet.” “I’m so curious about what will happen.” Why not? Point of view aligned with a clear intention, “I’m going to learn something new at this meeting or event,” can radically shift your experience and the outcome. Taking the time to notice habitual, negative, limiting points of view and craft alternatives requires awareness and time.

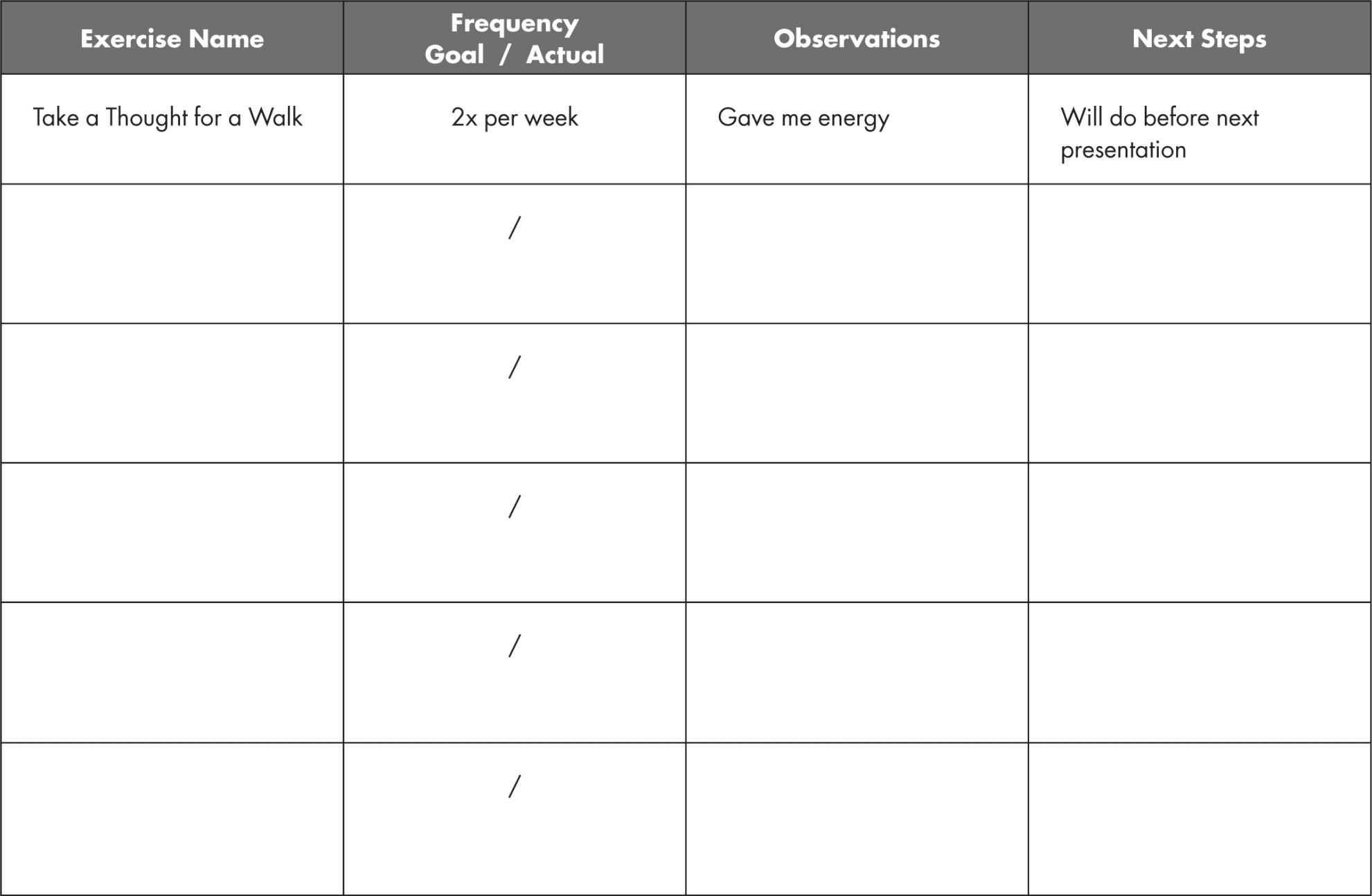

TRY THIS: TAKE A THOUGHT FOR A WALK

Ready to play? Pick a fun, even wacky, point of view and go do an errand. Here are a few to play with: “I’m gorgeous!” “Everybody loves me.” “Nothing scares me.” “Awesome day!” “I always get what I want.” Go to the grocery store or the bank. Walk around and see how it influences what you observe, how you communicate, and how others respond to you.

I once was at a conference where I’d been the keynote speaker the day before. I was in a terrible rush to make a flight, but it would have been very rude if upon entering the conference center I didn’t stop to speak to people who wanted to ask me questions. I picked the point of view that I was invisible. Actually, I went farther than that and decided I was clear. I focused on that for a few moments, tucked my head down, pulled up my shirt collar, hoped attendees would be in meetings. Much to my surprise, I discovered that they were all on break. “I’m clear, totally clear; they cannot see me” was all I thought over and over. No one saw me. Not one person … because I was clear! (Or maybe just see-through!)

Day in and day out, each of us has no end of choices of how to deal with the challenges ahead. How often do we choose our thoughts in a direct and immediate way? In the present moment? We can practice shifting our habitual thinking patterns moment by moment. We can practice the cessation of thinking (which, for most, is merely obsessing over the same tired worries), being present in the moment and harnessing our powers to solve problems and create new inventions. We can consciously shift our point of view as we would consciously solve a math problem.

The beauty of shifting our point of view is that the results are immediate. An altered point of view will quickly be integrated by the body. If one consciously chooses the point of view “I’m excited to see what’s going to happen” and then pairs it briefly with the physical gesture of happy clapping hands, even just for a few seconds, the emotional body will quickly begin to shift. A shift from, “I’m terrifed I’ll mess up,” to “Everything will be fine,” coupled with arms raised in victory and repeatedly whispered “Yes! Yes! Yes!” can change you and the outcome.

Actors do these sorts of things all the time as a way of preparing for an entrance. How does an actor make the audience believe he’s just come inside from a raging snowstorm when everyone knows he’s just entered from backstage? He brings the cold in with him by doing all manner of physical gestures that conjure up the weather outside and its effects on his body. And not just the weather but what happened to him before he came on. Did he run into his beloved? Did he have an argument with a neighbor? Whatever emotional and physical experience he encountered before entering the stage must be embodied so it rings true and is communicated clearly. The same practices could be employed by nonactors were they taught the means to do so.

Sometimes I suggest to those who worry about how they’re perceived or who have impostor syndrome that they try on the point of view “I’m a subject expert,” “I’m the best,” or “I really know my stuff.” Or as with Clair in the Introduction, “I’m queen.” Often they’ll counter that that’s egocentric or too “showy.” And I agree that using that point of view as a way to get attention for oneself will indeed come off as egocentric. But to be a subject expert in service to an organization is not making it all about you; it’s about making you more effective for the workplace, so that you have the confidence to deliver what’s needed. On the other hand, with those who are arrogant and quite full of themselves, I suggest they try the point of view “How can I help?” “What don’t I know?” And for those who are stressed to the maximum and feel that the entire organization will fall apart if they take a sick day, I ask them to take a few deep breaths, imagine a walk on the beach, and say the point of view “It’ll be OK” or even “So what?” The results are invariably amazing.

FRAME SHIFT

The operative word here is play. We take ourselves so seriously. We move in the same limited repetitive ways day in and day out. Yet we have so many options. How rarely, past the age of 9 or 10, do we actually play? Play for adults is confined to sports, video games, crossword puzzles, dinner parties, or the occasional concert, dance performance, or art exhibit. But opportunities for play are available every moment of the day.

TRY THIS: WORD MOVE

Take a piece of paper and tear it into one-inch strips. Write down a word on each strip; choose any random words but preferably nouns. Fold up the pieces of paper and toss them into a bowl. Stand up. Relax. Take a few deep breaths. Shake out a bit. Pick one of the folded strips of paper, open it, and read the word. Without any thought, as quickly as possible, let the body instantly react to the word by making a grand movement or gesture that expresses your reaction to that word. Relax. Pick another word. React. And another. Observe the thoughts that come into your head as you do this.

I’ll repeat that: Observe the thoughts that come into your head as you do this.

Note the judge, that voice that puts this exercise down as foolish, embarrassing, or infantile. We ridicule play. We find it wasteful and unproductive. It doesn’t make anything. It just is. Of course, it is the very isness of play that is so valuable. To play, one must be able to surrender to the moment, to give in to whatever happens next without trying to control it. To just be. What thoughts came to you as you attempted this exercise, if indeed you allowed yourself to do it? How loud were those thoughts that “judged” you? Were you able to ignore them, or did they stop you in your tracks? What were the precise words that came to you? Did they sound familiar? Have you heard them before? I’ll bet you have. And here’s the kicker—why do they have any validity at all? Why do we listen to the self-sabotaging judge when all it does is stop us from playing and stepping beyond the limits it sets? Who made the judge the arbiter of what is permissible?

There is a difference between the self-sabotaging judge and the socialized mature adult: the former is a joy-killing internal voice, and the latter is essential for society and the workplace to function. We inherit all these limits, set well before we had any say in the matter. But then we carry them inside for the rest of our lives, often without questioning them. But the all-knowing judge—that punishing inner voice that criticizes with such impunity—is very different from the observant self, and the two should not be confused with each other. The judge is a killer. It kills spontaneity, joy, play, impulse, risk. It’s wedded to shame, ego, pride, and guilt. If you live in its shadow, it always wins. Even if it only crops up occasionally, you cannot win a fight with the judge. You cannot negotiate with the judge. It lives in a part of the self that is so ancient and rooted to early childhood unconscious memory that at best all you can do is recognize it and attempt, as best you can, to ignore it.

TRY THIS: OUT LOUD

Pick another word out of the bowl, read it, gesture, and say out loud all the things the judge is saying about you or the exercise. By saying the words of the judge out loud, you can actually hear those words and begin to distance yourself from the judge and observe how it limits risk taking on so many levels.

You may think, “I can’t play like that. I can’t be inappropriately silly. I have to be professional, reliable, and mature.” Certainly one can’t be inappropriately silly in a business setting. But what the unconscious, global judge does is limit us everywhere. It just doesn’t pipe up occasionally. It seeps into our daily life and saps creativity and fun at every juncture. It haunts us. Those who operate under the judge’s orders never break free. They second-guess what they want to say in meetings; they cut off their creativity, refuse risk, and avoid the new. People for whom the judge is ever present are terrified of failure, embarrassment, and humiliation, so they operate within very routine, confined, safe borders. Interestingly, certain businesses and corporations actively use this fear to their advantage and attract employees who, despite great intelligence and talent, are terribly risk averse. Not very fun places to work. Is that how your place of business operates? Is that what initially attracted you? Is that where you wish to stay?

By trying “Word Move” and “Out Loud,” you’re providing yourself the opportunity to isolate and hear the judge in a controlled and safe setting. Only by objectively hearing and isolating its overtly critical voice can you begin to drop it. And that is all one can do, because you cannot negotiate or win a fight with the judge. It will always win. Dropping it, like discarding heavy luggage that weighs you down, is the only choice. How?

TRY THIS: JUDGE’S JOURNAL

To grow muscles that are aligned with the part of the self that is not identified with the judge—muscles indifferent to external ideas of “success” or “being right,” muscles that take you into the moment and beyond “results”—it’s important to identify the specificity of your own personal judge. One of the best ways to do this is to write down what the judge actually says. Buy a small diary and carry it with you. As you notice what the judge says, write it down. Get it out of your head and onto a piece of paper. Externalize it. Carry the notebook everywhere for several weeks and jot down random judge comments and thoughts. Don’t reread the comments or the journal.

TRY THIS: JUDGE’S JOURNAL REPLIES

After a few weeks of making entries, sit down and read the entire judge’s journal. Do you notice certain themes? What are they? Bucket together all those that fit into clear themes and title the themes. Now write down an alternative thought to what the judge says. If, for example, a constant theme is “You’re not smart enough,” what might you reply to that? “I didn’t get this far by being stupid.” Or “There are many kinds of intelligence.” Or “I can learn what I don’t know.” Write those down in a new journal. Finding an alternative to the ever-critical judge is the first step to getting out from under its destructiveness. As you train yourself to find alternative thoughts and ignore the judge, you’ll begin to discover how much more creative, fun, and successful your day becomes. This is a frame shift, literally turning a thought upside-down so that you can see the world differently.

Why write by hand? Why not do it on computer? One reason for writing in a small diary is privacy. Another, it can always be tucked in a pocket and carried with you. But most importantly, handwriting slows us down. It uses gestures that are deeply ingrained in our neural circuitry. Handwriting allows for a deeper connection to what is experienced. It creates a quiet self-communion that a keyboard cannot provide.

IMAGINATION

When I discussed point of view with a client, she remarked, “In golf it’s called the swing thought.” Her golf pro had taught her to actively imagine the golf swing in her mind’s eye before she physically did it, to visualize first the swing and then the trajectory the ball would take. Mind maps of habitual movements that help us to predict where the body needs to go happen automatically. The intentional visualization of a physical act is a bit different and is a discipline. It needs to be practiced as much as the physical act of actually swinging the golf club. But it needn’t be just for sports or movement. One can visualize any number of things before a meeting, a presentation, or any high-stakes communication. Often, due to stress, we tend to imagine the worst. But with a little bit of effort, changing the movie inside the mind can alter the eventual outcome.

Before your next high-stakes presentation, don’t allow your imagination to hurl you down a path of negatives—typically, “What if I forget my words or lose my place?” As a matter of fact, this is the most common anxiety I encounter. It’s OK. Everyone forgets words. Just roll with it. If during a presentation you do forget a word, say aloud, “Oh, what’s the word I’m thinking of?” You’ll be amazed by how sympathetic people will be, sometimes even supplying the missing word for you! Sometimes people worry about blushing or shaking. To blush is to be. It’s your passion expressing itself and is nothing to be ashamed of. Own it! Also, amazingly, when people stress about blushing or blotching, and I’ve coached them to “love their blush,” it has sometimes completely disappeared. Regarding shaking, there are exercises provided later on that help to ground the arms and legs. The key thought here is to create a different mental image of the outcome.

TRY THIS: STANDING O

Before a high-stakes presentation or meeting, imagine instead your body is a rooted, tall, very strong tree that is grounded and secure. Imagine the audience giving you a standing ovation and calling out “Bravo!” It’s almost guaranteed that won’t happen, but it is a preferable vision to help you launch your talk and dispel the natural anxiety that comes with any big presentation than the typical ones driven by fear. You may even enter the meeting with excitement instead of dread!

So much happens inside the head. In order to connect, it’s vital to understand the degree to which your physical body aligns with your thoughts to create the bonds that will allow you to succeed. Recent studies suggest that meditation, long demonstrated to reduce stress and promote calm and well-being, can also train attention itself. For a long time, attentional blink, a brain phenomenon where things happen far too fast for the brain to detect, was thought to be a fixed, immutable property of the nervous system. But it’s been determined that attention itself is a skill that can be enhanced, trained, and increased. It is not fixed at all but actually quite flexible. Increasingly, we are learning that what we believed to be immutable is utterly fluid; it is merely our perception that is stuck. Recent research into intelligence is demonstrating that it too is plastic and can change and grow. The notion of a fixed IQ may soon enter the dustbin of history!

The same can be said of the judge. Habitually negative points of view restrict the imagination. As deeply ingrained and habit-driven as we are, with practice, focus, and attention, habitual thoughts can be shifted. They can be modified so as not to work against you, but for you. Precisely because our emotions are so contagious, playing with these kinds of mental and physical shifts can also greatly benefit those with whom we interact and alter the social sphere and scripts in which we live and work.

Chapter 1: Use Your Head

Speaking/Posture

✵ Happy/Sad Mouth—emotion-body feedback loop

✵ Sweet Apricot: Jaw Relax—jaw tension

✵ Head Hinge—subtext from head position

✵ Broken Bridge—emotion-body feedback loop, posture

✵ Wet Dog—relaxation, voice-body connection

✵ Head Hinge with Voice—throat tension-head position impact on voice

✵ Reverse Turtle Neck—posture, proper head placement, voice

Seeing

✵ Star Eyes—eye communication

✵ Just an Inch!—muscle memory/habit

✵ Habit Breaker—micro-movements, unconscious habits

✵ Mirror Talk—observe unconscious habits

Listening

✵ Elephant Ears—focus, relaxation, listening

✵ Inner Ear—focus, attention, thought observation

Thinking

✵ Take a Thought for a Walk—thought-emotion-body feedback loop

✵ Word Move—identify inhibitors/impulse work, observe judge

✵ Out Loud—observe/separate from judge

✵ Judge’s Journal—externalize the judge

✵ Judge’s Journal Replies—create alternative modes of thinking

✵ Standing O—imagination, positive self-coaching