Getting There: A Book of Mentors (2015)

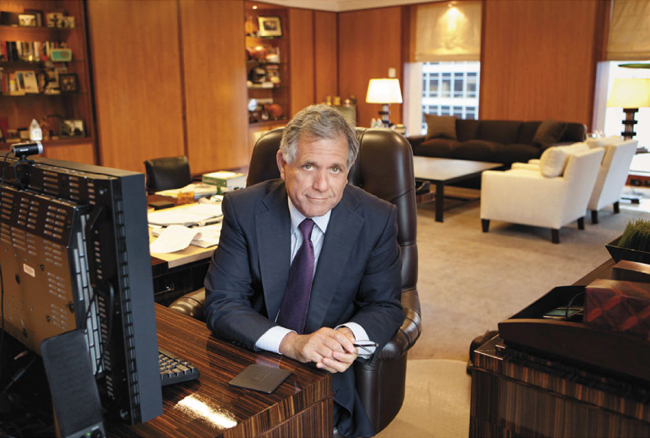

LESLIE MOONVES

CBS PRESIDENT AND CEO

I never liked a day of school in my life. Be it elementary school, high school, or college—it didn’t matter. I was always bored and couldn’t wait until class was over. To me, it was all just a means to an end. I attended Bucknell University and was initially premed, but that was only because I didn’t have a strong interest in anything else. Plus, it made my parents very happy.

Before long, I realized that the sciences and I were not made for each other. Talk about not being interested! So I gave that up, went off to Europe, and spent my junior year at the University of Madrid. I had a great time, but I still had no idea what I wanted to do with my life.

Upon returning to Bucknell as a senior, I had to pick a major. Because I had just spent a year accruing Spanish credits, I selected Spanish. But I also became active in the theater department that year. An extraordinary professor named Harvey Powers ran the program and was an inspiration to me. He thought I had a talent for acting and suggested a few graduate schools. I followed his advice and got accepted to a two-year program at the Neighborhood Playhouse in New York. It was, and still is, probably the best acting school in the country.

From there, I ventured into the world of professional acting and started to get some work. Most of it was guest-star spots on television shows. Although the roles sometimes got a little bigger, I was never immensely successful and had to tend bar at night to pay my bills. The life of a partially employed actor created a lot of tension because it wasn’t stable. I had to wait around for auditions to come my way. I couldn’t plan my life. I couldn’t plan on going on vacation. I couldn’t plan on a steady stream of income. My hand was always out—as if I were saying, “Please like me!” I did not feel in control.

At a certain point I looked around and realized that despite my amazing training I was never going to be a great actor. I observed my contemporaries and realized that many of them had a lot more talent than I did. I was mediocre at best. My teacher at the Neighborhood Playhouse, Sandy Meisner, once said something that really stuck with me. He said, “You should only be an actor if acting is the only thing you can do.” I realized that that wasn’t me.

A friend of mine, the actor Gregory Harrison, had started a small production company, and we decided to produce a play together. The play was good, but it became way more successful than we had imagined because of a fluke. Our play was being performed in a tiny theater in Hollywood. One day, the man running the Ahmanson Theatre, the biggest theater in LA, came to see it because he was a friend of one of the other producers. He happened to come the day Natalie Wood drowned—and Natalie was supposed to star in the next production at the Ahmanson. So he took our little play instead and moved it from our ninety-nine-seat theater to his three-thousand-seat theater! It was a tremendous break. It was my first big paycheck and it enabled me to buy my first house.

At that point I left acting behind and moved forward producing theater. I realized I had strong organizational skills and was a good leader. I loved getting up in the morning, being busy with creative stuff, and feeling productive. It gave me a stable income and a stable life. I felt like I could control my own success. The harder I worked, the more successful I became. I was greatly relieved.

It’s difficult to specifically map out your career. Things sometimes come at you and hit you in the face. If your path is rigid, you’ll likely miss out on opportunities. You have to be fluid and open to change. I shifted from acting to producing theater and realized it felt great. Before long, I shifted again and got my first job in TV as a development executive at Columbia Pictures Television. That felt great too.

In contrast to my disinterest in school, I was a passionate student of the television industry. My goal was to figure out the game and how to win. I was like a sponge. I asked questions, talked to everybody I could, and spent a lot of time trying to figure out which executives were smart and which ones weren’t.

One way to learn is through observing great mentors, but it’s perhaps more valuable to learn by observing people with important jobs who you think are doing it wrong. In other words, you can gain a lot by looking at a person and thinking, If I had that problem, I wouldn’t do it that way. There are more mediocre executives out there than good ones, so you can pick up a lot by just keeping your eyes open.

Ironically, one of the reasons people say I’ve done well in television is because I am easily bored. I constantly say, “Keep me entertained!” and I think that helps me find good content. My experience as an actor has also provided me with an advantage over some of my competitors. I know what it’s like to audition, and I’m still very involved in casting a lot of our projects. I’m impressed by good acting and love that part of my job.

What may surprise some people, because I know I have a reputation for being kind of cocky, is that as a young executive I was pretty insecure and underestimated my capabilities. As I moved up the ranks, I always expected there to be greatness from my colleagues at each new level. I worried that I might not measure up. But when I got there, I usually realized that my new contemporaries were not as untouchable as I had imagined them to be and that I could catch onto things pretty quickly. The lesson is: don’t automatically be intimidated by people who have achieved more professional success than you, and don’t let your own insecurity bog you down. Move upward if you have the opportunity. Once you have the chance to survey the lay of the land, things are often not as hard to tackle as you might have imagined, and the people you assumed were so smart might not be.

When I was hired as president and CEO of CBS in 1995, the network was in last place and there was a loser mentality among the employees—which I hated. It was especially difficult for me because I had just come from Warner Bros. Television, where we were the number one studio and I was leaving a group of people that I really liked. For the first eighteen months, it wasn’t fun getting up in the morning. It was a really difficult time. The main problem was that I was not surrounded by a great team, so we had to make a lot of changes. We wanted to hire a bunch of fresh, talented employees—people with good character who wanted to win—to replace those who were not working out with the company. There was a lot that went into it, and it was hard work every step of the way, but as a team we were eventually able to turn the ship around and bring the network from last to first place.

I am a big proponent of teamwork. Certain companies operate on a system of people trying to outdo or compete with one another. I don’t believe in that. We win together (no one person gets all the credit) and we lose together (no one person gets all the blame). There are about 150 people involved with every television series we do. Some shows end up being hits, but two out of three fail. It’s awesome when you have a hit, but when you have a failure with great people, you have to make them feel good about working with you again. And you can do that with the team theory: “It’s not your fault. We win as a team, we lose as a team.” And it’s true—it takes a team to put on a show. By the way, people who are not team players don’t understand that by not supporting the team—by looking for self-aggrandizement instead—they’re only going to hurt themselves.

How you handle those around you is key to how you get ahead. If I find someone good, I try to hang on to him or her. It’s essential to let employees feel secure about their jobs. Some companies don’t, and the employees work out of fear and are constantly watching their backs. When my employees drive to work in the morning, I want them thinking 100 percent about their jobs and not about whether the guy in the next office is going to screw them or whether they are going to be fired. That leads to nonproductivity. If people feel secure where they work, their performance is so much better.

I’m someone who assumes that what can go wrong will. In my business we can only control fifty percent of what we do—so it’s imperative that we look ahead, identify possible pitfalls, and work our butts off to control what we can. That doesn’t mean that things won’t go wrong, but if I know I’ve done everything I could, then I don’t feel as bad if they do (also, it makes our chances of success that much greater). I hate self-inflicted wounds. They bother me a lot.

LESLIE’S PEARLS

![]() If you want to pursue a career in my industry, get in the door any way you can and then do the best you can at that job, even if it’s sweeping the floor of a production office. If you do the best job you can, somebody will notice, and opportunity will present itself. Let people see that you are willing to do anything and that you have a good attitude. When I walk down the halls, I notice people who are upbeat. The number one thing is to let others think of you as a “can-do” person. My daughter Sara is like that. I could tell her, “I need an elephant on my lawn at six tomorrow morning,” and she’ll have it there. No questions asked. Those are the kind of people who get ahead, the kind who don’t necessarily ask questions but instead find solutions.

If you want to pursue a career in my industry, get in the door any way you can and then do the best you can at that job, even if it’s sweeping the floor of a production office. If you do the best job you can, somebody will notice, and opportunity will present itself. Let people see that you are willing to do anything and that you have a good attitude. When I walk down the halls, I notice people who are upbeat. The number one thing is to let others think of you as a “can-do” person. My daughter Sara is like that. I could tell her, “I need an elephant on my lawn at six tomorrow morning,” and she’ll have it there. No questions asked. Those are the kind of people who get ahead, the kind who don’t necessarily ask questions but instead find solutions.

![]() When you have to say no, do it nicely. We get pitched about five hundred television shows a year and only put four new ones on the air—so there’s a tremendous amount of rejection going on—but we want those same people to come back to us when they have a hit show. If you’re a creator, a writer, or a producer who’s spent a year working on a TV show, it’s your baby. You don’t want to hear someone say, “Your baby’s ugly.” You want to hear something more sensitive like “Okay, it didn’t work out this time, but if you do it in the right way, maybe next time.” There are ways to get a clear message across without unnecessarily hurting feelings and burning bridges.

When you have to say no, do it nicely. We get pitched about five hundred television shows a year and only put four new ones on the air—so there’s a tremendous amount of rejection going on—but we want those same people to come back to us when they have a hit show. If you’re a creator, a writer, or a producer who’s spent a year working on a TV show, it’s your baby. You don’t want to hear someone say, “Your baby’s ugly.” You want to hear something more sensitive like “Okay, it didn’t work out this time, but if you do it in the right way, maybe next time.” There are ways to get a clear message across without unnecessarily hurting feelings and burning bridges.