Getting There: A Book of Mentors (2015)

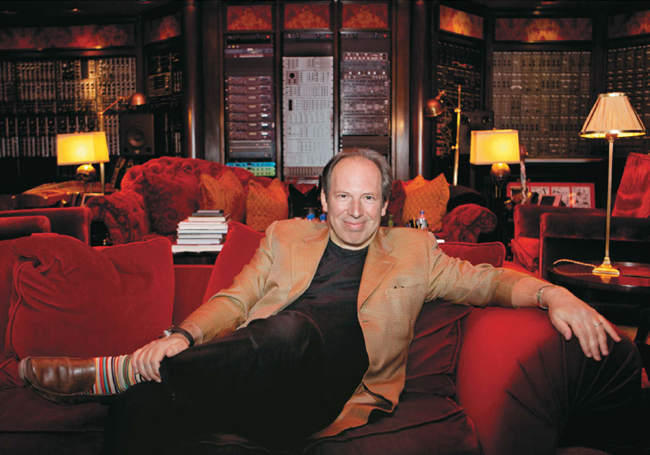

HANS ZIMMER

COMPOSER

I grew up in Munich, Germany. My mother was very musical and attached to old world tradition. She took me to my first opera when I was about three, then dragged me to classical concerts at least once a week until I was about twelve, at which point I rebelled. All I wanted to do was listen to loud rock and roll.

My father was a successful engineer and inventor who was ahead of his time and not afraid to try new things. He came up with all sorts of crazy inventions, some of which actually panned out. He died when I was six. My mother was devastated and filled with worry as to how we were going to get by. I wanted to put a smile on her face and remember thinking, I’ll play the piano! We lived far away from any other kids and didn’t have a television—so I carried on playing the piano and took great refuge in it.

It wasn’t long before I stopped playing the classics my mother wanted me to play and began to modify the piano any way I could. I wanted to figure out how to make new sounds. I know my father would have thought my experimentation was fantastic, but it made my mother gasp in horror.

The prevalent view in Germany at that time was that if you didn’t follow the rules and do well in school you wouldn’t amount to anything. Looking out for my best interest, my parents and teachers tried to get me to conform, but I was beyond salvage from the start. It wasn’t that I was a bad child; I just couldn’t stop my mind from wandering. When on occasion I did tune in, I would interrupt and question everything. My grades, of course, were terrible. If anything came after an F, that’s what I should have received. A teacher once threw a chair at me in music class. I was kicked out of nine schools and wound up at a boarding school in England. I was continually told that I would end up in prison. As a last resort, my mom sent me to a typing class.

What I loved—and did in all my spare time—was make music. On account of my father’s profession, I was introduced to computers at a very young age and embraced them as musical instruments. I also began playing keyboards and synthesizers as a teenager. My lack of formal music education didn’t matter (I did once take two weeks of piano lessons, but I quit because I didn’t like the structure). The technology was just being invented so everyone had to make things up as they went along.

I remained in England after boarding school where I played in seedy clubs and dives with a few pop bands—the most well-known being the Buggles, who sang “Video Killed the Radio Star.” In the meantime, I did other music-related gigs. I composed jingles for commercials and music for BBC miniseries, and I was known as the Synth Wiz because of my skills at programming that instrument.

Making a lot of money has never motivated me—and for many years I had hardly any. Similar to my experience with schools, I often found myself getting chucked out of apartments for not paying the rent. It wasn’t deliberate, however—the truly important, existential things never quite filtered through my daydreams. On one hand, being a poor artist sucked, but in many ways it was a grand life. I was surrounded by other poor artists. At the end of the day we would all sit around a table, have interesting conversations, then suddenly pick up our instruments and make music together. That created a feeling I couldn’t find anywhere else. Days went into nights, and nights went into mornings. The only time we noticed that we didn’t have money was when the electricity would get turned off.

Eventually, I took a job as assistant to the composer Stanley Myers. We scored a few films together (including My Beautiful Laundrette) then decided to start our own recording studio. We worked on fusing music from traditional instruments with electronic instruments. The first film I was hired to do alone was called A World Apart. The director Barry Levinson later got a hold of that soundtrack and hired me to score his film Rain Man, my first Hollywood job and a real turning point in my career.

I had imagined that Hollywood was going to be technologically far ahead of anything I’d seen in Europe, but when I arrived, I found it to be quite the opposite. Composers there were not yet using computers, which made the dialogue between them and the director very cumbersome. The composer would play his tune on the piano and have to say something like “This is where the French horns come in.” The director had to imagine what that would sound like. The first time a director could actually hear the music would be when a full orchestra was assembled. What if he didn’t like it? Making changes was a lot harder. I, on the other hand, composed the Rain Man score on my computer in Barry Levinson’s office. He loved that he could listen to my work as it was forming. Instead of making him imagine what the French horns would sound like, I’d bring them in on the computer.

Rain Man went on to win the Oscar for Best Picture and earned me my first Academy Award nomination. This led to jobs on an increasing number of high-profile films such as Thelma & Louise and Driving Miss Daisy, among others.

The people behind The Lion King heard some of my music and offered me the job, which I took for all the wrong reasons. The other movies I had worked on were not geared toward children. I now had a six-year-old daughter and wanted to show off by taking her to the premiere of a film that I had scored. What surprised me was that I really got into the story—which is about a son losing his father. Because I lost my father at a very young age, I was able to tap into a profound and honest part of myself. It was the first time I expressed serious emotions through music. I ended up winning an Academy Award, a Golden Globe, and two Grammys for The Lion King. You never know what can come from a humble children’s movie if you approach it honestly and genuinely.

Music is a huge part of the tone of a film, but my job isn’t to do precisely what directors ask. If they knew exactly what they wanted, they would do it themselves. My job is to create something that they can’t imagine: a parallel story expressing what’s not already present in words and images. By the time a film is handed to me, everyone else has done all they can to make it as good as possible. Inevitably, some parts don’t live up to what people imagined so, because I’m the last in line, they’re all hoping I’ll be able to fill in whatever is lacking. Although I am always incredibly excited when someone comes to me with a job, I also always feel a tremendous sense of responsibility and pressure right from the start.

Having people love what you do is seductive. Like most artists, I know how to repeat something that’s been a success, but if I start just regurgitating what I’ve done before, I’m not growing. The only way I can maintain this life is to go directly against that temptation and create new things. I feel very fortunate to keep getting work, but because I’ve done so much, I have an underlying fear that I have nothing left in the drawer. I’ve got twelve notes to work with—and every other composer is using those same twelve notes. I wonder, What’s going to make what I do so different from what everybody else does?” I become terrified that I will let everybody down, including myself.

The first step in the process is to understand the movie’s story. It doesn’t take long for a possible framework to start sparking in my head, but translating that into a tune is agonizing. Sometimes it takes me two or three weeks of just sitting in my studio—sixteen, seventeen, eighteen hours a day not coming up with anything. I get obsessive and can even work myself into a panic. Don’t invite me to a dinner party. I’ll probably forget to show. I’ll say, “See you at seven o’clock,” but then at ten to seven an idea will pop into my head. I’ll think it will only take me two minutes, but the next time I look at my watch it’s two in the morning. It’s not that I forgot about the dinner party; it’s that real life doesn’t even exist. Of course, this trait has been a problem in my marriage, but let’s not even start that discussion! When I’m in a real panic, I literally don’t go home for the weekend.

Part of the problem is that I’m a perfectionist. Even when the tune is complete, there’s often a little critic sitting on my shoulder saying, “It’s no good. It’s no good.” It’s not uncommon for me to continue working on something until the director or producer comes to me and says, “The movie has to come out. Give me whatever you’ve done right now.” Even at that point I fight tooth and nail for more time. I know every trick in the book and have a thousand excuses as to why it’s not ready or why I may even need to start over again. I drive people crazy, of course—myself most of all.

I was hired to do the score for the film The Dark Knight. On the last day of recording with a one-hundred-person orchestra, I found myself lying on the couch in the back of the room experiencing terrible chest pains. I hadn’t slept in weeks and was thinking, I’m going to die. But I didn’t say anything. Chris Nolan, the director, who knows me very well, saw that I was in serious trouble. He walked over to the microphone and announced to the musicians, “I think we’ve recorded enough. You can all go home.” I sat up and said, “No, no, no, no! We haven’t!” Chris repeated, “I think we’ve recorded enough.” And, of course, he was right.

After all these years, I have come to realize that I must go through a period of agony and torture before I have a breakthrough. My big ideas frequently come at the very last moment, when a deadline is beating me up like crazy. I think we all have some fear of failure in us, and it’s a great motivator. Sometimes, however, I really do have to accept defeat. I’ll realize that something I’ve been working on for weeks isn’t good and I will chuck it out. I used to feel terrible when this happened and I resisted getting rid of anything—but I have come to realize that it’s part of the creative process and now I am prepared for it.

HANS’S PEARLS

![]() If you look at the downside of any vocation, you can find a million reasons not to pursue it. But if you try to play it safe and pick a career because you think you should, it most likely won’t end well. Whenever I need legal or medical advice, I stand up in front of my orchestra and announce my problem. Half of the musicians are doctors and the other half are lawyers whose parents forced them into those jobs.

If you look at the downside of any vocation, you can find a million reasons not to pursue it. But if you try to play it safe and pick a career because you think you should, it most likely won’t end well. Whenever I need legal or medical advice, I stand up in front of my orchestra and announce my problem. Half of the musicians are doctors and the other half are lawyers whose parents forced them into those jobs.

![]() People used to tell me to find a real job. Hearing this worried me deeply, but not enough to give up music because I was so passionate about it. At one point somebody (I believe it was James L. Brooks) told me that it’s okay to do the thing you love. That sort of freed me up to relax into what I do. I still check with myself every morning and ask, “Do I want to go to the studio and write music?” To this day, it’s the most exciting thing I can think of doing.

People used to tell me to find a real job. Hearing this worried me deeply, but not enough to give up music because I was so passionate about it. At one point somebody (I believe it was James L. Brooks) told me that it’s okay to do the thing you love. That sort of freed me up to relax into what I do. I still check with myself every morning and ask, “Do I want to go to the studio and write music?” To this day, it’s the most exciting thing I can think of doing.

![]() My music has often been ahead of its time and, as a result, easy to criticize. When I was a teenager, hearing people cut down work I was proud of was very painful. But as time progressed, the feedback went from my mother’s neighbors complaining about the “ungodly noise” I was making to them asking, “When is your son coming back to play some of that beautiful music again?” The main difference was their perception. I was basically playing the same thing.

My music has often been ahead of its time and, as a result, easy to criticize. When I was a teenager, hearing people cut down work I was proud of was very painful. But as time progressed, the feedback went from my mother’s neighbors complaining about the “ungodly noise” I was making to them asking, “When is your son coming back to play some of that beautiful music again?” The main difference was their perception. I was basically playing the same thing.

![]() Your worst qualities can also be your best, so try to utilize them in a positive way. In my case, the characteristics that got me thrown out of school ended up making me successful in my career. Music-related thoughts are always whizzing around my head, and I compose through daydreaming and questioning things. I’m also very stubborn, which has been a huge advantage because I stick with things when others might not.

Your worst qualities can also be your best, so try to utilize them in a positive way. In my case, the characteristics that got me thrown out of school ended up making me successful in my career. Music-related thoughts are always whizzing around my head, and I compose through daydreaming and questioning things. I’m also very stubborn, which has been a huge advantage because I stick with things when others might not.

![]() It’s essential to work with people you feel safe being completely candid with. When I was scoring The Power of One, the director first wanted the music to be similar to what’s in the film Out of Africa, with big, lush orchestras. I suggested we do the whole thing with Zulu choirs instead, which he eventually thought was a good idea. I started working with a couple of choirs in Los Angeles—but no matter what I did it kept sounding like gospel music. I used up the entire budget but was still not happy with the outcome. I finally went to the producer and said, “I have to admit defeat. Let’s just scrap my Zulu idea and I’ll write the nice orchestral score that the director originally requested.” The producer said, “The only mistake you are making is that you’re not in Africa.” That was on a Thursday. By Monday morning I was in a township in South Africa, in a warehouse with two microphones and this incredible choir rocking the roof. It was amazing.

It’s essential to work with people you feel safe being completely candid with. When I was scoring The Power of One, the director first wanted the music to be similar to what’s in the film Out of Africa, with big, lush orchestras. I suggested we do the whole thing with Zulu choirs instead, which he eventually thought was a good idea. I started working with a couple of choirs in Los Angeles—but no matter what I did it kept sounding like gospel music. I used up the entire budget but was still not happy with the outcome. I finally went to the producer and said, “I have to admit defeat. Let’s just scrap my Zulu idea and I’ll write the nice orchestral score that the director originally requested.” The producer said, “The only mistake you are making is that you’re not in Africa.” That was on a Thursday. By Monday morning I was in a township in South Africa, in a warehouse with two microphones and this incredible choir rocking the roof. It was amazing.

![]() Creative people should try to do something new every day. Whether it ends up being good or bad doesn’t matter. What’s important is to keep your muscles exercised. You’ve got to practice a lot before you can be any good at most things. The majority of skilled musicians I know have been practicing about eight hours a day from the time they were six or seven years old. I played all day long and still do. One of the reasons I continue to work so much is that when I’ve taken any lengthy break I feel rusty when I return. I imagine it to be the way a runner trains every day. If he stops for any period of time, his muscles atrophy and he’ll have to work even harder to build them up again.

Creative people should try to do something new every day. Whether it ends up being good or bad doesn’t matter. What’s important is to keep your muscles exercised. You’ve got to practice a lot before you can be any good at most things. The majority of skilled musicians I know have been practicing about eight hours a day from the time they were six or seven years old. I played all day long and still do. One of the reasons I continue to work so much is that when I’ve taken any lengthy break I feel rusty when I return. I imagine it to be the way a runner trains every day. If he stops for any period of time, his muscles atrophy and he’ll have to work even harder to build them up again.

![]() Take the time to know your technology. I see many musicians completely relying on recording engineers and producers because they are not up to speed on the current tools. I think, This is your baby and you are letting other people do all that stuff to it? The last thing you want to do is to be at the mercy of someone else.

Take the time to know your technology. I see many musicians completely relying on recording engineers and producers because they are not up to speed on the current tools. I think, This is your baby and you are letting other people do all that stuff to it? The last thing you want to do is to be at the mercy of someone else.