Brick by brick: How LEGO Rewrote the Rules of Innovation and Conquered the Global Toy Industry - BusinessNews Publishing (2014)

Part II. Mastering the Seven Truths of Innovation and Transforming LEGO

Chapter 6. Exploring the Full Spectrum of Innovation

The Bionicle Chronicle

Bionicle is the toy that saved LEGO.

—Jørgen Vig Knudstorp, CEO, the LEGO Group

BY 2005, HAVING RECONNECTED LEGO WITH ITS CORE consumers and markets, Knudstorp, Nipper, and other leaders concluded they couldn’t put the company on a long-term growth curve simply by refreshing LEGO City police cars and fire stations. To generate enough profits to propel LEGO into a healthy future, they’d also have to pursue a variety of innovations that create new markets. To figure out a way forward, the management team took a look back at the company’s recent past.

When the company’s senior managers delved into the past decade’s three most successful LEGO toys—LEGO Star Wars, LEGO Harry Potter, and Bionicle—they saw that the lines had one thing in common: each drew on a full spectrum of innovations to complement the core LEGO sets. The rich story line, compelling characters, and licensed merchandise of a property such as Star Wars brought in new revenue streams and helped boost sales of the kits beyond Billund’s most optimistic forecasts. The one drawback with Star Wars, from the LEGO Group’s point of view, was that a sizable percentage of the line’s profits went back to Lucasfilm, as specified by the licensing agreement.

Like Star Wars, the wildly successful Bionicle line also featured a wide variety of complementary innovations. Bionicle, launched in 2001, was built around a new business model, pioneered new sales channels and markets, and was founded on a magnetic story line that played out over many years—and thereby augured many years of robust revenue. Best of all, because Bionicle had been invented in Billund, the majority of its licensing profits flowed back to LEGO. So when Knudstorp and his team began to roll out the second phase detailed in “Shared Vision”—manage for profit and prepare for growth—the team that had created the toy called Bionicle provided a road map for moving LEGO into the future.

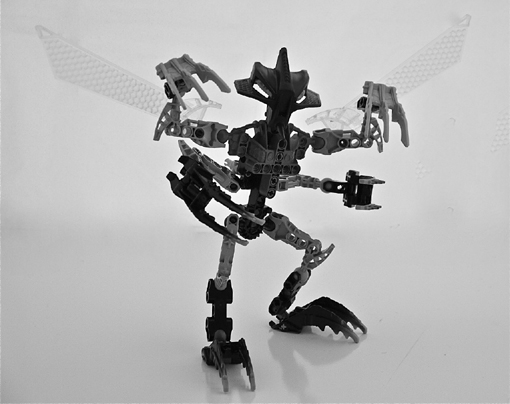

Gorast, a Bionicle from the 2008 Mistika line. According to lego.com, “Makuta Gorast is known throughout the universe for her raw power and violent rage.”

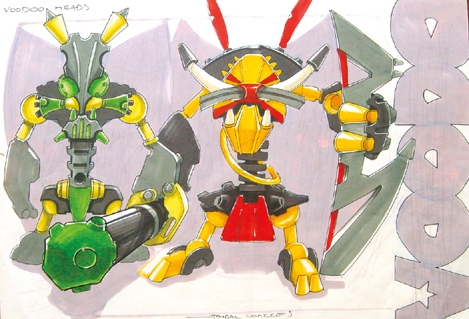

The Bionicle story actually arcs back to the summer of 1999, when a development team from LEGO visited the offices of Advance, a Copenhagen-based advertising agency, with a concept for a decidedly different line of LEGO toys. Initially titled Voodoo Heads, the line of exotic action figures was to be targeted at what industry insiders call the “craze category”: flash-in-the-pan toys that strike it hot for a season and then flame out. The plan was to package Voodoo Heads in plastic canisters and sell them for less than $10. LEGO asked the Advance team, which included an art director named Christian Faber, to help create background visuals for the Voodoo Heads advertisements.

As he tucked into his new assignment, Faber, who earlier had worked on the LEGO Star Wars line, thought back to how the movie’s spellbinding narrative and riveting characters drove the LEGO Group’s sales to record heights. Voodoo Heads showed a glimmer of that same Star Wars mojo. Inspired by the talismans of voodoo practitioners, the Voodoo Heads characters—freaky, skeletal figurines—were unlike anything else that had come out of Billund. Faber was captivated by the opportunity they presented. Instead of drawing static backgrounds for ads, he decided to push beyond the Voodoo Heads characters and instead illustrate an epic, multipart adventure such as Star Wars, which would amp up his client’s revenues for many years to come.

For Faber, the inspiration for this new, illustrated narrative came from his recently diagnosed brain tumor. The tumor was benign, but it would spread if he didn’t take a daily injection of medication.* Reflecting on the illness that fired his imagination, Faber “had the thought that when I took these injections, I was sending a little group of soldiers into my body, fighting on my behalf to rebuild my system. Then it all just came together.”

Faber imagined the toy canisters as vials of medicine drifting toward the head of a giant, comatose robot that was infected with a virus. The medicine’s active ingredient was an army of nano-size creatures that arrived in pill-shaped capsules, entered the titan’s body, and fought to liberate it from the virus. The story played out in a microscopic world, but for its “part-organic, part-machine” inhabitants, the scale was sweepingly vast. Faber provided visual depictions of the island and its inhabitants and also suggested to his colleagues at LEGO a name for the new toy: Bionicle, a combination of the words biological and chronicle. (Insert photo 12 shows two of Faber’s early concept sketches for the toy. Insert photo 13 shows the pill-shaped canisters that were the packaging for the 2001 launch of Bionicle.)

Scripted by a LEGO story team, the inaugural Bionicle narrative kicked off with six hulking heroes, the Toa Mata, arriving on a tropical island called Mata Nui. They venture into a strange world of massive domes, swamps, and underwater caves, where they encounter Rahi, Bohrok, and Piraka—savage beasts controlled by a supervillain, Makuta Teridax. The Bionicle creatures, which resembled mechanized gladiators, were as exotic as the plot—and, as it turned out, they were a powerful kid magnet.

With its sinister look and feel and a roiling story featuring dozens of characters doing battle, LEGO Bionicle was a sensation for Poul Plougmann and his team—the only unmitigated success, besides LEGO Star Wars and LEGO Harry Potter, to come out of Billund during the early 2000s. Bionicle artfully melded the LEGO building experience with the storytelling and adventure of an action figure saga. And it employed a full arsenal of innovations, with a constantly unfolding narrative delivered through the Web, a book series, direct-to-video movies, licensed apparel, and comic books. Bionicle was a worldwide hit that almost single-handedly sustained LEGO through the depths of its fiscal crisis.

In 2001, its inaugural year, Bionicle’s sales exceeded $160 million and the Toy Industry Association declared it the year’s “Most Innovative Toy.” In 2003—the year the rest of LEGO came crashing down—Bionicle’s soaring sales accounted for approximately 25 percent of the company’s total revenue and more than 100 percent of its profit (as the rest of the company was tumbling to a net loss), making it a financial anchor in turbulent times. By mid-2004, while Knudstorp and Ovesen were busy closing down unprofitable lines and selling off assets, the LEGO Bionicle website averaged one million page views per month and the toy spawned a host of fan-generated sites. That year, retailers sold a Bionicle set every 1.4 seconds. By the end of the toy’s nine-year run, LEGO would sell some 190 million Bionicle figures, more than the combined populations of France, the United Kingdom, and Italy; 85 percent of American boys ages six to twelve would know the Bionicle brand, and 45 percent would own at least one Bionicle toy. The Bionicle book series, numbering forty-six books, regularly topped the sales lists for young adult fiction. At one point in 2003, the DC Comics Bionicle books, with a circulation of 1.5 to 2 million copies every other month, were the world’s most widely read comics.

With its vibrant story line and rich universe of characters, Bionicle was also the company’s first successful, internally developed intellectual property, or IP.† In a very real sense, Bionicle was the LEGO Group’s own, homegrown Star Wars, and it let LEGO take on the role of licensor and put the brand’s imprimatur on a plethora of products. Bionicle-crazed boys could snag a simple Bionicle toy with a Happy Meal (from McDonald’s), kick around in Bionicle sneakers (Nike), retrieve a Bionicle video game from a box of Honey Nut Cheerios (General Mills), show off their favorite brand with Bionicle lunchboxes (DNC), amp up their cool factor with Bionicle T-shirts, sneakers, and backpacks (Qubic Tripod), and dream their Bionicle dreams while tucked into Bionicle-themed bedding (Dryen). Because LEGO invented the Bionicle IP, all the royalties from the sales of all that merchandise flowed back to the company’s coffers.

When Knudstorp looked back to the birth of Bionicle, he saw more than the emergence of a supremely successful moneymaker for LEGO. The line demonstrated the value-creating potential that came from pursuing a wide array of interconnected innovations. Back when the rest of LEGO was running off the rails, the Bionicle team not only invented a new toy category, the buildable action figure, but also created new business models, forged diverse partnerships, pioneered markets, concocted a streamlined product development process, and delivered to customers an immersive play experience. Thus Bionicle presented a rough prototype for developing and bringing to market a full spectrum of complementary innovations. At the close of 2005, as Knudstorp looked for a way to coordinate the company’s disparate innovation efforts, he found a model in the process that gave birth to Bionicle.

In all, the Bionicle team launched eight complementary innovations, which helped usher in a new era of profitable creativity at LEGO.

A New Building Platform

Full-spectrum innovation begins with a product platform that’s sturdy enough to support a broad range of complementary innovations. In 2005, Knudstorp had two very different models to learn from: Bionicle and Galidor. Both themes attempted to create complex story lines, rich play experiences, and a broad array of revenue streams. While Galidor, with its limited building experience and underwhelming story, was an expensive failure, the Bionicle platform was entirely different.

More than a few veteran LEGO executives believed Bionicle was too different. In the traditionalists’ view, Bionicle breached the sacred LEGO principle of open-ended play. After all, it was the Bionicle story, not the brick, that invested the toy with meaning. A boy could build a Toa Mata model, but when he was done, he wouldn’t understand what he’d created—unless he knew the story. There was also the vexing matter of some distinctly creepy play themes that dwelled within Bionicle. Take, for example, the Bohrok, a race of insectoid creatures controlled by brain-eating parasites called Krana (see insert photo 14). With characters such as Krana and the Bohrok, Bionicle was more akin to the sci-fi horror film Alien than to the family-friendly LEGO sets that Godtfred Kirk Christiansen had long ago imagined.

Knudstorp, however, disagreed with the toy’s critics. In Bionicle, he saw a team that was competing from an original innovation playbook that nevertheless summoned the company’s DNA.

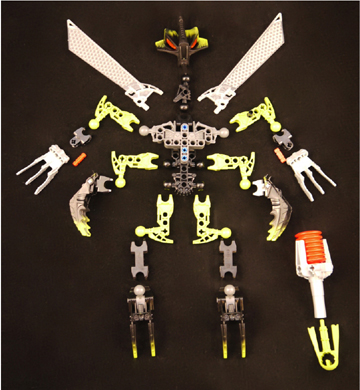

Although Bionicle was distinctly different from any previous LEGO toy, it was rooted in the company’s foundational touchstones. The characters still must be assembled, just as with LEGO. Bionicle incorporated LEGO Technic pins and gears, which meant the components from one Bionicle model were interchangeable with other Bionicle models, in the same way that components from other LEGO kits were interchangeable. And Bionicle hewed to the fundamental LEGO play experience, “joy of creation,” even as it introduced a new LEGO building platform.

The core of the Bionicle building platform, and a defining characteristic of the toy, was the newly created ball-and-socket connector. With this mechanism, a character’s leg was topped off with a ball-shaped joint, which could be inserted into the hollow socket of the character’s hip. The leg could then be easily rotated. For the first time, boys could build LEGO figures that featured fully articulated heads and limbs, which added a degree of realism that couldn’t be found in more static plastic beings such as the minifig. This multibillion-dollar breakthrough put the “action” into this buildable action figure and ushered in a swarm of knockoffs from the likes of Mega Bloks and Hasbro. Thus the Bionicle building platform took the System of Play in a new direction while at the same time remaining faithful to it.

Bionicle was far from an overnight success. It took nearly five years and many trial-and-error experiments to bring the line to life. The toy evolved from an idea to a real-world product largely because its development team was tenacious enough to keep grinding away at a challenging problem: how to keep kids who had outgrown LEGO System sets (such as City) from abandoning the LEGO brand before they were old enough and skilled enough to take on the more challenging LEGO Technic line of products. But perseverance didn’t come at the expense of prudence. LEGO management didn’t bet on Bionicle until the development team had launched two earlier products, Slizer and RoboRiders, and learned through real-world experience what worked and what didn’t. Although Slizer was a minor hit and RoboRiders an outright failure, creating those toys pushed the team to test the market and learn from its mistakes.

The ball-and-socket joint, which allows a character’s arms and legs to rotate, was developed specifically for Bionicle. The pins that connect the hands to the upper arms were borrowed from the Technic line.

The earliest concepts for the toy that became Bionicle date back to the mid-1990s, when LEGO mapped out a strategic brief that charged the development team with creating introductory sets of LEGO Technic models. The goal was to drive multiple purchases by conjuring models that were so enthralling—or, to use Christian Faber’s term, so crazed—boys would collect multiple sets.

From the very start, different functional groups within the development team, which was drawn from the Technic design group, contributed breakthrough ideas.

✵ The design team came up with the notion that the LEGO models should be inspired by manga, visually dynamic Japanese comics featuring robots, space travel, and heroic action-adventure themes.

✵ The engineering team invented the ball-and-socket connectors, which let boys build character-based models featuring an unparalleled range of motion.

✵ Meanwhile, someone from marketing suggested that the toy could be sold through nontraditional (for LEGO) retailers, such as gas stations and convenience stores.

Based on those insights and innovations, the team identified the cornerstones of the customer experience: the toys would be collectible; they’d feature memorable characters; they’d be priced for pocket money, so kids (as opposed to only parents) could buy them; and they’d be sold through everyday outlets that kids visited on a weekly or monthly basis. No previous LEGO product line had ever combined those four traits.

Not only did the development team break down the walls between corporate departments and cross-collaborate—with engineers, marketers, and designers for the first time working side by side—the team also stretched the notion of what constituted a LEGO play experience. “We really wanted to rock this world,” said Søren Holm, formerly the team’s design chief. “We had a mantra: concepts with an attitude. There was a lot of internal competition [between different LEGO development teams] at that time. Who was the best? Who dared the most? We dared. We dared big-time.”

The initial result of their daring was Slizer (see insert photo 9), one of the first lines in the company’s history to be based on characters that LEGO itself had developed.‡ The line consisted of eight robots from different planets that warred with one another for territory. (In North America, the toy was dubbed Throwbots, a name that referenced the robots’ capacity to sling small, collectible discs, which were inspired by the Tazo discs found in packets of Frito-Lay chips). Looking like mechanical men made out of winches and helicopter parts, Slizer was so alien to anything LEGO had ever created, management couldn’t agree on how to brand the line.

“Was it Slizer from LEGO? Was it LEGO Technic Slizer or LEGO Slizer from Technic? They were so afraid of destroying what we came from and going into this new world,” recalled Holm. “It was really an uphill launch. They didn’t think it would work.”

Despite management’s skepticism, Slizer was founded on a compelling market opportunity. It presented an original concept: the toy market’s first buildable action figure. And unlike the vast majority of LEGO sets, whose sales were mostly generated during the make-or-break Christmas season, Slizer was priced and promoted to create sales throughout the year. Thus it produced uninterrupted, year-round revenue. Launched in early 1999, Slizer generated sales in excess of DKK 600 million (about $100 million). To management’s surprise, LEGO had a hit on its hands.

A New Channel to Market

After Slizer, LEGO managed to pull defeat from the jaws of victory. The company’s strategy was to phase out Slizer after one year and replace it with another short-term, collectible product line. By the time RoboRiders (shown in insert photo 10), a line of six vehiclelike creations with special powers, roared into the market in December 1999, it was too late for management to reverse course and extend Slizer’s run. The company’s leaders could only hope that Slizer’s success would fuel RoboRiders’ performance.

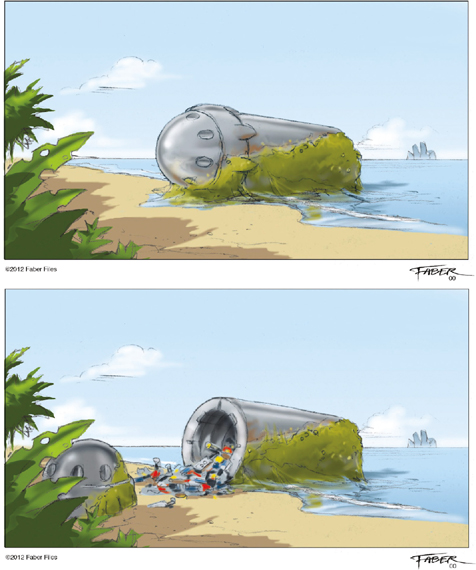

Like Slizer, RoboRiders had a backstory: the six motorcycle-style vehicles battled a viral force that was attacking their worlds. And like Slizer, RoboRiders aimed to be a collectible, less-expensive toy that kids could purchase in supermarkets and other nontraditional outlets. RoboRiders also introduced one of the company’s most unconventional innovations in packaging. The design team fabricated a clear, soda-can-style canister to package the toy, based on the notion that RoboRiders characters might be sold in vending machines.

Although full-spectrum innovation starts with creating a market-defining product, it also encompasses the critical moment when the product meets the customer. Delivering RoboRiders via vending machines amounted to a novel sales channel for LEGO. Whereas all of its other lines were sold through big-box retailers in the United States and the smaller toy shops that were so abundant in Europe, RoboRiders opened a new front: gas station stores and other purveyors of inexpensive impulse items. The team, having learned its lesson from Slizer, began planning for a multiyear run of the toy if it proved successful.

But RoboRiders never took off, largely because the line lacked the vivid personalities and compelling characteristics that would draw kids in. Sales were lackluster, and the company pulled it off the shelves after little more than a year.

Despite the setback with RoboRiders, the development team continued to believe it had found a winning formula. Feedback from the market—in the form of sales results, field reports from LEGO salespeople, and a cold-eyed analysis of what had worked and what had failed—helped the team reset its strategy for the toy that became Bionicle.

An Epic Story

Slizer proved that a story-driven, character-based line could deliver repeat purchases and year-round revenue. RoboRiders demonstrated that a toy delivered at a low price to nontraditional outlets held promise, but the characters couldn’t be too abstract. To hold kids’ interest, character-based toys should be founded on an episodic story line with plenty of teasers hinting at new adventures to come. Taken together, Slizer and RoboRiders also delivered a painful lesson: the development team couldn’t sustain the relentless pace required to turn out an entirely new product line every year. A better tack was to aim for a story that could be told over many chapters, like a serialized movie. Such an innovation would open up a revenue stream that could flow for years. Based on those insights, the team repositioned the concept for its next buildable action figure: Voodoo Heads, which would morph into Bionicle during the summer of 1999, when Christian Faber and his Advance colleagues were brought into the project.§ (Insert photo 11 shows two early concept sketches for Voodoo Heads.)

With Voodoo Heads, the team retained the foundational cornerstones of the Slizer consumer experience—the concept would still be collectible, character-based, highly affordable, and sold through everyday outlets. The team also incorporated the most promising innovations from RoboRiders, such as the canister-style packaging and the notion that the line should be launched through a Web-based promotion, which was still a relatively fresh concept for the toy industry of the late 1990s. What the new concept would most need, though, was an epic, movielike narrative that would sustain interest and sales for many years to come.

Among the significant breakthroughs that helped Voodoo Heads evolve into the Bionicle story, three stand out. First, there was Faber’s rich depiction of the Bionicle universe, with its tropical island topped by a massive volcano. “For me, every fantasy story starts not with the characters but with the location,” he recalled. “You’ve got to give kids a compelling place to play.”

An early Voodoo Heads prototype.

The next breakthrough came when Bob Thompson, the leader of the Bionicle story team, used Faber’s visuals to recast the characters. Taking inspiration from Maori culture, Thompson changed the names of the six main protagonists from the pedestrian-sounding Axe, Blade, Flame, Kick, Hook, and Claw to the more evocative Lewa, Kopaka, Tahu, Phoatu, Gali, and Onua. The words were nonsensical, but they resonated with kids by conjuring an exotic land.

The final missing element came when the development team, working with Bionicle’s writers, invented the Kanohi Masks of Life, which released great power to those characters who possessed them. The protagonists’ search for the Kanohi Masks catalyzed the story and gave it a narrative thrust. Bionicle was not only about a battle between good and evil forces but also about a quest for a “hidden object of power.” Moreover, the masks became the most prominent of the franchise’s collectible elements. Just like the Bionicle characters, kids gained power among their peers when they acquired a Kanohi Mask.

“Erik Kramer, who was a product manager for Bionicle, literally interrupted a meeting to show me the [original] mask,” recalled Nipper. “He was saying, ‘We’ve got it now. The mask is going to make all the difference.’ And he was right. Until then, we’d had a very bumpy ride with Bionicle. We really weren’t sure just how good an idea it was. But after the mask was born, the communication, story, packaging—everything just flowed like a river.”

The Kanohi Mask of Life.

A New Way of Connecting with Customers

A full spectrum of innovations creates value not only via new products and services for customers but also from changes to a company’s business model, internal processes, and even its culture. And for LEGO, inventing Bionicle was very much a culture-altering event. The challenge of creating a new play experience pushed the Bionicle development team to solicit feedback from the outside world, which in the 1990s represented a dramatic break from standard LEGO practice. From the birth of the brick to the last years of the past century, designers were so secure in their knowledge of what kids wanted that they rarely ventured beyond Billund to glean insights into children’s lives and apply what they learned to their next creations. To the extent that LEGO designers ever listened to kids and adult fans, those consultations almost always took the form of a kind of reluctant due diligence. Except on the rare occasions when a focus group unanimously disparaged a toy, consumers were brought in simply to fine-tune and validate products that were inevitably destined for the market.

Because Bionicle, as well as the Slizer and RoboRiders toys that preceded it, sought to introduce boys to a story-driven fantasy world, the “designers know best” mind-set had to change. Starting with the assignment that led to the creation of Slizer, the design team sought to acquire a far deeper understanding of its potential consumers and use that knowledge to better position its toy concepts and guide their development.

The effort began when the Slizer team, working from published research on boys’ behavior and especially their play lives, created detailed profiles of four different consumers, each with an alliterative name. There was Agent Anthony, who loved action movies and adventure stories. Systematic Siegfried was fascinated with technology. Artistic Arthur would probably grow up to be a craftsman. And then there was Bully Bob, easily distracted and the loudest kid in the room—hardly the typical LEGO consumer and one whom the company had never seriously pursued.‖ Each of the archetypes informed Slizer and helped shape Bionicle, but none more so than Bully Bob.

“With the Bully Bob character, the model’s functions and look and feel had to be very different,” said Holm. “We started to give life to concepts that had many more competitive twists to them. There was also a social aspect, which got us thinking about how boys might play in groups, rather than alone. When we gave birth to those types of concepts, the whole world opened up. It felt like we were on to something.”

The team’s outreach to kids led to a crucial insight early in the development of the toy. When it tested Voodoo Heads, the team worried about the conflict that came with the concept. Part of the play experience involved one character punching the other, causing its head to pop off. The team thought that kids from the United States, with their greater exposure to baleful movies and bloody TV shows, would go bonkers for decapitated characters. To its surprise, the team found just the opposite. Violence was a turnoff, because the American kids personalized the experience. There was also a practical consideration: the boys told testers they were afraid they’d lose the collectible heads if they blew off too easily. Having heard the customers’ verdict, the developers went back to their bricks.

As the concepts evolved from Slizer to RoboRiders to Voodoo Heads to Bionicle, Bully Bob morphed into Bionicle Boy, a dynamic trendsetter with a short attention span, a kid who likes to multitask and desires instant gratification. For the designers, Bully Bob and, later, Bionicle Boy were vital signposts for navigating the journey to develop the Bionicle line. When designers began to lose their way they referred back to the archetype, which reminded them, as Holm put it, to “always be a bit more daring.” Thus they pushed the features that would make the toy unique: vivid storytelling and richly drawn characters that wouldn’t bust a kid’s allowance, delivered a hefty dose of street cred, appealed to boys’ collecting instinct, and, above all, were cool.

Two years after Bionicle hit the U.S. market in the summer of 2001, the development team began working with kids and adult fans to help guide the evolving story line. The effort began by accident. In 2003, right around the time that the news media began reporting on the LEGO Group’s financial troubles, a rumor started circulating among LEGO user groups that the company was going to drop the line. Greg Farshtey, who had taken over as the lead writer of Bionicle books and comics, joined one of the toy’s fan sites, BZPower, to refute the rumor. Almost immediately, he began exchanging fifty to a hundred daily emails with kids. He soon found fans were an invaluable resource for testing ideas and gauging the story’s performance.

“A lot of what I wrote for the [Bionicle] books and website was in response to what kids told me they wanted to see,” said Farshtey. “If kids were saying they didn’t understand a certain part of a book, I knew we had a problem that needed to be fixed in the next book. I’d also poll kids with questions like, ‘What characters from the past eight years would you want to see on a team?’ I’d then use their choices to build the team. Interacting with kids gave us an instant read on everything we did.”

In the years following Bionicle’s launch, other LEGO development teams would go to far greater lengths to elicit feedback from beyond the company’s design studios. But more than any other product line, it was Bionicle that helped LEGO take its first tentative steps toward building bridges with kids and adult fans.

A New Development Process

In addition to changing the LEGO Group’s design culture, by demonstrating the value in seeking customers’ feedback Bionicle also left its imprint on the company’s development process. Because Bionicle was based on an episodic story line and new releases came out semiannually, in the off-season months of August and January, the team took a different approach to managing the clock. Back in the late 1990s, other LEGO creative teams used as much time as they needed to conceive a new toy concept and then presented it to management when it was ready for review. But the Bionicle team didn’t have that luxury. It set aggressive, six-month delivery windows and changed the models’ range and complexity to fit that schedule. This “time boxing” of the toy’s development, a common industry practice where managers set strict deadlines and adjust the scope of the project to fit those deadlines, was new to LEGO and later became a key feature of the revamped LEGO Development Process, in which new-product projects would be divided into three-month stages.

Equally important, the Bionicle team’s ability to kick out, every six months, a new story with a new set of characters proved to Knudstorp that LEGO could slash the time it took to develop new products, which in 2004 still averaged a very leisurely three years. Soon after he was elevated to the chief executive slot, Knudstorp launched the High Speed Project, which aimed to transform LEGO into a fast company that could nimbly respond to emerging market opportunities. When skeptics voiced doubts that LEGO could cut its product development time in half, Knudstorp had only to point to Bionicle to prove that it could.

Postlaunch, the Bionicle team managed the development effort very differently than the rest of LEGO did. The LEGO product development process in the late 1990s was a bureaucratic mess, with rigidly defined process steps, multiple review points, mounds of paperwork, and sign-offs at every turn. The Bionicle team did away with that approach and instead focused on the key information that management needed, so it could better determine if the team was on target. Some of that data came directly from customers. At a time when other LEGO teams often pushed products onto retail shelves with little input from customers, the Bionicle group’s deep investigations into what boys wanted in a buildable action figure gave managers a far better sense of what would sell. The line’s spectacular success encouraged the new management team, when it took over in 2004, to make consumer insight research and product testing with kids key features of the revamped LEGO Development Process.

The Bionicle team kept its efforts on track through regular review sessions with upper management, where executives critiqued model prototypes as well as the business case for the next iteration of Bionicle characters. Because LEGO had never before developed a story-driven product, the design team went to elaborate lengths to bring executives into the concept’s science-fantasy world. For its 2000 presentation of the Voodoo Heads concept (which was later renamed Bone Heads), the development team used big blocks of foam board to fashion a strangely wondrous island, eight feet high, replete with cliffs and caves inhabited by the skeletal creatures. The team’s working name for the proposed line read like the title of a B movie from the 1950s: Bone Heads of Voodoo Island. As Holm remembers it, Kristiansen and Plougmann were somewhat taken aback by the presentation’s scale and over-the-top setting. But the expressiveness of the Bone Heads characters, which evinced some of the ghoulish humor of Day of the Dead figurines, elicited the go-ahead to keep developing the concept.

Prior to the toy’s launch in 2001, no other LEGO development team had encountered quite as many hurdles as the team that created Bionicle. Not only did the Bionicle design crew have to meet the challenge of conjuring an entirely new kind of toy, but the writers had to compose the Bionicle narrative, the Web team had to conceive new digital content, the marketing team had to create a movielike campaign, the packaging team had to fashion the soda-can-style Bionicle canisters, and the licensing group had to coordinate with a multitude of companies that wanted a piece of the Bionicle brand. And then, to keep the story fresh and keep priming demand, everyone had to generate an entirely new story line, new characters, and new sets every six months.

Time and again, the development team could have lost its way. But for the nine years of the Bionicle franchise’s lifetime, the team kept to its path, largely because it found a different way to organize itself.

Before the rise of Bionicle, the LEGO Group’s product teams were siloed from one another and toys were for the most part developed sequentially: designers mocked up the models and then threw their creations over a metaphorical wall to the engineers, who prepared the prototypes for manufacture and then kicked them over to the marketers, and so on down the line. Rarely would one team venture onto another team’s turf to offer a suggestion or ask for feedback. If all went well, the team’s product would hit the market in two or three years.

The Bionicle team’s six-month deadlines forced a different way of working, one that was less sequential than parallel, and highly collaborative. Once the outline for the next chapter of the Bionicle saga was roughed out, the different functional groups would work side by side in real time, swapping ideas, critiquing models, and always pushing to simultaneously nail the deadline and build a better Bionicle.

“We had a massive project team,” recalled Farshtey. “It wasn’t just the creative people; it was also people from Advance and from marketing, sales, events, PR—all different parts of the company, all helping to steer the franchise.”

Because the marketing group worked directly with designers, Bionicle’s advertising campaign felt connected to the product. Promotional posters for Bionicle’s first-year run had the look and feel of movie posters, precisely because the toy featured the powerful visuals and narrative sweep of an epic film. “We wanted more communication in the product and more product in the communication,” said Faber. “That meant the marketing group needed to be involved at the very start of product development, so the story flowed out through the product. We wanted the product almost to tell the story by itself.

“We had a kind of triangle, where the marketing, the story, and the product had to move ahead together,” he continued. “None of those could be the spearhead. Each needed to support and inspire the other.”

The problem with a more linear approach to product development is that if, say, the marketing group isn’t engaged early on in the process, it might not spot a communication flaw until the problem becomes pervasive and therefore expensive to fix. With the Bionicle team, however, the tight linkage between design, marketing, engineering, and the other groups meant that little problems didn’t compound into big problems before the team could take corrective action. Moreover, because each functional group was invested in the entire project, as opposed to protecting its turf, everyone had a stake in driving the business forward. This made for an operationally resilient team and contributed to Bionicle’s nine-year run.

A New Way of Working with Partners

Team Bionicle’s leveraging of a full spectrum of innovations resulted in a new toy category, a new sales channel, a revamped development process, and a first attempt at soliciting ideas from customers. It also proved that breaking out of Billund’s insular culture and collaborating with partners could pump up the company’s bottom line. Just as no other LEGO development team was ever pushed to work as fast as the Bionicle group, no other marketing team was ever required to coordinate with so many external partners as the Bionicle group. The wide array of Bionicle backpacks, T-shirts, pajamas, and toys fueled the line’s profitability by delivering fat royalties, low operating expenses, and almost no risk. Moreover, licensed media products such as the Bionicle book series (published by Scholastic Books), comic books (DC Comics), video games (TT Games), and direct-to-video movies (Miramax) were the primary platforms for extending the franchise’s reach. Keeping pace with each initiative meant the Bionicle team had to ensure that every six months, when the product line’s next iteration hit the market, all those Bionicle books, backpacks, bedspreads, and the rest reflected the new toy’s look, story, and LEGO values.

To help all those different companies work with LEGO, the company set up an independent Licensing Group. The group, which reported to a different senior vice president than the Bionicle team, was responsible for ensuring that every partner’s product augmented the Bionicle brand and reflected the LEGO DNA. Through product review sessions, seasoned LEGO managers reviewed every licensee’s business plans, product concepts, and production samples. And the Licensing Group closely tracked each external partner’s progress in preparing its Bionicle-branded product for the market. The group’s progress reports served to alert LEGO when, say, the next Bionicle video game was straying from the toy’s story line or a T-shirt featured the wrong color scheme. Taken together, the critiques and reports helped ensure that the Bionicle team, through eighteen product launches, marched in tight formation with more than a dozen different partners.

Because each new version of Bionicle had a short shelf life, the team couldn’t afford to wait until after the toy’s launch to correct a partner’s mistake. The team learned this lesson the hard way. During Bionicle’s inaugural year, LEGO took too long to approve the final design of many licensed products, which meant the products weren’t launched until the new Bionicle line was nearing the end of its six-month life cycle, a painful delay that crippled sales. Realizing the need for speed, the team developed the Bionicle Style Guide, which helped accelerate and coordinate every external stakeholder’s product development effort.

Encompassing nearly fifty pages, the Style Guide, which outlined Bionicle’s rapidly evolving strategy, story line, and design, was delivered to licensing partners months in advance of a toy’s rollout. The 2006 edition of the guide, for example, delivered a sweeping overview of Bionicle’s three-year story strategy, along with visual and written profiles of upcoming characters such as Zaktan, aka “the Snake” (“100% animal, 0% pet”), and Toa Jaller (a “fearless lava surfer”). The guide also dug into Bionicle minutiae, with strict instructions on such granular details as typography (“trademark headlines are always all caps”) and Bionicle logo renderings (“always placed on the top of the layout”).

Taken together, the 2006 guide gave Bionicle’s partners a visceral depiction of the new lineup’s color palette, key visual backgrounds, packaging, design elements, and more. As a result, the richly detailed guide let partners align with the brand’s strategic blueprint. In 2008, when LEGO executives reviewed the company’s strategy for licensing, Bionicle was deemed the best at coordinating with partners, surpassing such iconic properties as LEGO City and the minifig.

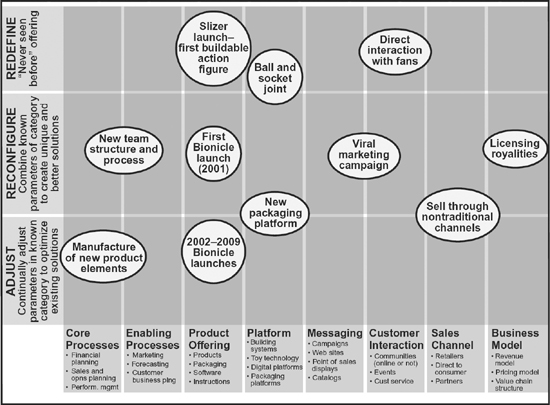

A New Road Map for Guiding Innovation

Throughout 2005, as Knudstorp and his team wrestled with the challenge of igniting profits by pursuing the full spectrum of innovation, their foremost goal was to set targets, define initiatives, and establish a sequence for getting things done. Here again, Knudstorp looked to the Bionicle team to point the way.

After many months of digging into the challenge of creating a cohesive model for full-spectrum innovation, a working group came up with a practical if unlovely vision for the entire company: innovation is the “focused introduction of a new idea … that improves the product, experience, communication, business, and process.” By expanding the definition of innovation beyond the “bright” parts of the organization that create new toy sets, the new definition expressly challenged every part of LEGO—sales, finance, manufacturing, and all the rest—to come up with game-changing ways to amplify the company’s performance.

LEGO managers identified four categories of innovation that mattered, with three types of innovation in each.

✵ Product innovations were new toys and platforms. Four years earlier, with Bionicle’s launch, the toy’s development team had already innovated in both of those categories. It had invented an industry first, the buildable action figure. In creating subsequent generations of Bionicle characters, the team was adept at making modest but highly profitable improvements to the line. And with its ball-and-socket connector, Bionicle also represented a new building platform for LEGO.

✵ Communication innovations included novel ways of marketing and also connecting to customers. Greg Farshtey’s outreach to customers via Bionicle fan sites, which he and his colleagues used to improve Bionicle’s story line, offered a proof-of-concept model for leveraging feedback from fans. (LEGO subsequently expanded on Farshtey’s example and uses it extensively today.)

✵ Business innovations consisted of new business models (such as new pricing methods or subscription plans) and new channels to market. Since its debut in 2001, Bionicle had already delivered minor but noteworthy innovations in both areas. With launches in the off-peak months of January and August, and a price tag that required just a few weeks of a boy’s allowance, Bionicle filled both a seasonal and a demographic gap in the LEGO brand’s market. Although the attempt to sell the toy through vending machines never panned out, Bionicle freed marketers to seek out unconventional ways of pushing beyond such conventional intermediaries as Walmart and Toys “R” Us. Perhaps most significant, the range of licensed products that Bionicle Boys snapped up delivered a healthy stream of royalties back to Billund. As a result, other product teams emulated the Bionicle model of partnering around LEGO-developed properties to boost sales and profits.

✵ Process innovations were core processes (where money changes hands) or enabling processes (such as new-product development). Here again, Bionicle suggested new innovation pathways for LEGO. The Bionicle team’s compressed development cycles and customer insight research became staples of the revamped LEGO Development Process. Bionicle proved it was indeed possible to cut development time in half, which resulted in substantial cost savings for LEGO. And it showed that customer research could improve the odds of delivering toys that kids fervently desired. That, of course, augmented the company’s sales.

Having defined the different areas of innovation that LEGO would pursue, the working group also recognized that “innovation” doesn’t necessarily mean “radical”—that, in fact, different opportunities require varying degrees of innovativeness. The new model spotlighted three different approaches to marshaling the kinds of change that would help LEGO advance its goals. The first, simplest type of innovation was to adjust existing toys—that is, to freshen up an evergreen line so that it attracts news waves of kids without adding significantly more development and manufacturing costs. After the first launch of Bionicle, each subsequent release was an exercise in making incremental improvements. Adding new features, new story lines, and (later) vehicles for the Bionicle characters were small but very profitable innovations. Senior vice president Per Hjuler captured the attitude of many LEGO managers when he asserted, “I am continually humbled by the power of the little idea.”

The next, more challenging innovation was to reconfigure—to change existing building systems or platforms to provide a new customer experience. LEGO had a blockbuster with its Star Wars toys and a minor but promising success with Slizer. Combining the two concepts to produce a set of buildable action figures with a rich, episodic story line meant that LEGO had to blaze a new path to profits, but it was starting from a familiar place. The result was a hit series of toys that generated significant sales for almost a decade. Reconfiguring innovations change the terms of competition in an existing market.

The most difficult and unpredictable innovation is the kind that redefines a category. Case in point: the 1998 Mindstorms RCX kits, the company’s first foray into robotics. (The second version of Mindstorms, released in 2006, was a reconfigure innovation for LEGO.) Another example was LEGO Universe, an online game where kids from all across the planet could connect and play. In the next two chapters, we cover each of these radical attempts at redefining LEGO play.

The LEGO Group’s senior management put all these definitions onto a single page—an innovation matrix—that it used to map the kinds of innovations it would pursue. In the first year following the crisis, the company focused most of its efforts on the adjusting kind of innovations—the lowest-risk, surest-reward section of the matrix. Later, when LEGO gained momentum and began generating profits, it took on the more ambitious innovations, reconfiguring and redefining. But LEGO always made sure it continued to seek out the everyday innovations that simply enhanced an already profitable line. So long as it innovated around its customers, sales channels, business processes, and the rest, LEGO wouldn’t always have to churn out a Bionicle-size blockbuster every year. Sometimes a simple makeover of an already successful line would suffice.

The LEGO innovation matrix, with some of the major innovations from the development of Slizer, RoboRiders, and Bionicle.

![]()

As it turned out, Bionicle racked up its peak sales in 2002 and then began a long but very profitable return to earth. By the time the line was phased out in 2009, the Bionicle business was much like the sleeping giant Mata Nui—still a force, but considerably diminished. And yet, while many factors beyond Bionicle have shaped the LEGO Group’s approach to guiding innovation, the team that created the toy has left an indelible mark on the way LEGO works. Thanks to Bionicle, what once was considered heresy at LEGO is now a kind of orthodoxy.

Bionicle proved it was possible to roll out a new product every six months instead of taking three years. By developing detailed profiles of different consumer segments, the Bionicle team took the first steps toward achieving a deeper understanding of the world as seen through children’s eyes and using those insights to build more desirable toys. In the late 1990s, such a thing was anathema to LEGO. Today, a dedicated consumer insights team plays a pivotal role in every LEGO product launch.

Further evidence of Bionicle’s influence on innovation is that cross-functional product development teams are now the new normal at LEGO. “Every team has a triangle-type arrangement,” said Søren Holm. “Design, engineering, marketing—they all work hand in hand.” Additionally, the move by Bionicle’s writers to glean guidance and feedback from consumers presaged a far more robust effort to cocreate with fans. And Bionicle’s successful licensing business pioneered new pathways for partnering with the makers of complementary products.

The Bionicle team’s rituals and practices for seizing on the full spectrum of innovation are now replicated all across LEGO, and that is Bionicle’s most enduring legacy. It’s no longer enough for development teams to simply propose a new product. LEGO management expects team leaders to plot it on the innovation matrix and demonstrate what other, complementary innovations will add to the concept’s revenue stream. Having learned that complementary innovations are too important to be left to chance, teams use the matrix to create and deliver them.

Bionicle was not just the toy that kept LEGO from falling into bankruptcy in 2003. It taught LEGO a far more expansive definition of innovation, one that need not be confined simply to products. It showed that while not all innovations are created equal, even incremental innovations can be highly effective, especially when combined into a complementary suite. LEGO codified these insights by creating the innovation matrix and requiring every development team to map their ideas to it. As a result, the matrix ensured that a full spectrum of innovations wasn’t an occasional outcome but a required result. And, as we’ll see in Chapter Ten, the company later reorganized itself around the matrix, thereby making it plainly evident which business unit was responsible for each type of innovation. Thus, the Bionicle team provided LEGO with an enduring, best-case example for guiding an expansive innovation effort. By looking back at Bionicle, Knudstorp was able to cast a bright light into the future.

* Thankfully, Faber’s medicine worked, and he was able to tell us his story ten years later.

† We use “IP” as shorthand for a company’s intellectual property, which can include patents, trademarks, and copyrights. These properties can become some of a company’s most valuable assets. Although LEGO had to send a portion of the profits from its licensed Star Wars toys to Lucasfilm, it could keep all of the profits from its Bionicle toys, since it owned the Bionicle IP.

‡ In 1979 LEGO introduced a set of toys around a theme called Fabuland, with characters, stories, and comic books accompanying the toys. The line never really caught on and was discontinued.

§ The concept went through many iterations and was also called Voodoo Bots and Bone Heads.

‖ Recall that Bionicle was developed under Poul Plougmann, who wanted LEGO to appeal to the larger market of boys who were indifferent to the brick. Most of those efforts failed. Bionicle was the one shining success.

Early LEGO

Photo 1. The duck, a wooden LEGO toy from the 1930s, occupies a special place in LEGO lore. When young Godfredt told his father that he had saved time and money by only using two coats of varnish on a batch of ducks, his father made him go back to the train station, get the ducks, and stay up all night adding the third coat. The story is used to illustrate the maxim “Det Bedste Er Ikke For Godt.” (Only the best is good enough.)

Photo 2. A LEGO Town set from the 1960s promised a play experience that was “real as real.”

Photo 3. One of the LEGO Group’s many innovations under young Kjeld Kirk Kristiansen was the introduction of fantasy themes such as Space. The 1979 Space Cruiser was a big hit.

Experimentation at LEGO : 1999-2002

Photo 4. The LEGO & Steven Spielberg MovieMaker set was an attempt to find a “blue ocean” market opportunity.

Photo 5. In the early 2000s, LEGO phased out the DUPLO brand in favor of the new LEGO Explore brand. The LEGO Explore Music Roller was one of the first toys to feature the new brand.

Photo 6. LEGO Digital Designer, developed by Qube Software, allowed users to create virtual LEGO constructions and upload them to a LEGO website.

Photo 7. The Galidor action figure, introduced in 2002, had a full spectrum of complementary innovations, including a new building system, a TV show, and a video game.

Photo 8. Between 1996 and 2002 LEGO launched three LEGOLAND theme parks in the UK, US, and Germany.

The Evolution of Bionicle

Photo 9. The Slizer line, launched in 1999, was the toy world’s first buildable action figure and a precursor to the Bionicle figures.

Photo 10. The RoboRiders line, launched in 2000, never took off and was pulled from the market after little more than a year.

Photo 11. Building on the success of Slizer and RoboRiders, LEGO sketched early concepts for Voodoo Heads, the toy that would become Bionicle.

The Birth of Bionicle

Photo 12. Two of Christian Faber’s early concept sketches from 2000 for the toy that would become Bionicle. Note the pill-shaped container that delivers the Bionicle heroes to the island of Mata Nui.

Photo 13. The canisters used to package the Bionicle toys in 2001 were very similar to the concepts drawn by Christian Faber.

Photo 14. The innovations tracked in these two pages culminated in Bionicle, a line that was far darker and more violent than anything LEGO had offered before and was an immediate hit with boys around the world.

Open Innovation at LEGO

Photo 15. The four original Mindstorms User Panel members (standing) were selected from the LEGO fan community and invited to help the LEGO team develop the next generation of the product. In the back (from left to right) are Steve Hassenplug, John Barnes, David Schilling, and Ralph Hempel. Kneeling in front are the LEGO Group’s Søren Lund (left) and Paal Smith-Meyer.

Photo 16. The LEGO Architecture Fallingwater kit.

Photo 17. Adam Reed Tucker, a Chicago architect who had created massive LEGO models of famous buildings and landmarks, worked with Paal Smith-Meyer at LEGO to develop the Architecture line of toys.

LEGO, Minecraft, and 3D Printers

Photos 18, 19, 20. LEGO fans can now design and replicate kits in their homes. Above is a re-creation of the LEGO Architecture Fallingwater kit in the online game Minecraft. Using a fancreated conversion program, that model was sent to a 3D printer to create a physical version, shown left next to the original LEGO Fallingwater kit. Finally, the fan-designed re-creation was “printed” using a Makerbot 3D printer, shown bottom left.

The Birth of LEGO Games

Photo 21. The original proposal for LEGO Games. Notice the Innovation Matrix in the lower left and the management team’s votes in the lower right. Management was asked to rate each concept according to how well it met the criteria of “never seen before,” “obviously LEGO,” and its potential to achieve annual sales of DKK one billion (about $200 million) per year.

Photo 22. LEGO dice prototypes. The final version is shown in the lower right of the photo.

Photo 23. Ramses Pyramid, one of the first sets in the LEGO Games line.