Impresario: The Life and Times of Ed Sullivan - James Maguire (2006)

Part I. A SHOWMAN’S EDUCATION

Chapter 5. Café Society

THE GRAPHIC, TO THE RELIEF OF RESPECTABLE NEW YORKERS, published its last issue on July 7, 1932. The following day, the city’s daily dose of 2-cent scandal mongering suspended publication. The paper had filed for bankruptcy on July 2, by one account collapsing under $3.1 million of liabilities. Part of this astronomical sum was a string of unpaid libel judgments, two for $500,000 a piece, and at least two more for lesser amounts. Controversial to the end, the paper’s demise provoked street demonstrations as unpaid printers and tradesman paraded up Varick Street with an effigy of Bernarr Macfadden, shouting what a reporter described as “uncomplimentary ballyhoo.” The cops had to be called to contain the crowd.

For weeks afterward there was talk of bringing the Graphic back—optimistic scuttlebutt about investors who might be interested—but nothing came of it. In truth, the mood had passed. Those oversized headlines about suicide pacts between flappers and married men were titillating when the paper’s readers had an extra nickel in their pocket. But the deepening gloom accompanying the long breadlines at Broadway and 47th Street had caught up with the Graphic. The paper was from a different era. Other scandal sheets, like The Tatler and Town Topics, were also felled by the Depression.

One week before the paper closed, Ed received a call from someone identifying himself as Captain Joe Patterson, the publisher of the New York Daily News. Would Ed like to be a Broadway columnist for the News? The caller invited Sullivan over to discuss the terms of his new employment. Ed could hardly believe his good fortune—in fact he didn’t believe it. As soon as he put down the phone he was consumed with doubt. Could the call have been a prank? Perhaps someone he had offended in his column was exacting revenge with a cruel practical joke. Or so Ed thought; fortune this good couldn’t be trusted. He immediately phoned the Daily News and asked: had Joseph Patterson just called him? Yes, it was verified, it had been Patterson. Amazing—Ed had just been offered a job. Relief competed with euphoria.

Getting a call from the Daily News publisher was like being called up to the big leagues. Patterson’s father had published the Chicago Tribune, and Patterson had been the Tribune’s editor. During his army stint in World War I the flashy British tabloids had caught his eye, and he guessed the formula would succeed in America. Soon after Patterson launched the Daily News in 1919 it became a rousing success.

Originally called the Illustrated Daily News because of its emphasis on photos, this first modern American tabloid also proved to be one of the hardiest. It would survive through the decades as the majority of newspapers from that period were swallowed by larger papers or ceased publication. The Daily News continues to be one of New York’s leading papers.

The News spawned a legion of competitors. The Graphic had been inspired by the News, and its booming circulation also impressed William Randolph Hearst. Soon after the tabloid’s initial vaulting success, the newspaper magnate tried to buy it rather than compete with it. When Patterson refused to sell or stop publishing, Hearst launched a competing tabloid, the Daily Mirror. (Hearst’s strategy was to hire journalistic superstars, hence Winchell’s post as a Daily Mirror columnist.)

Patterson, an ardent socialist in his youth (though later highly conservative), wanted to publish a paper for the working man. Its style would be straightforward, and it would eschew lofty analysis. But if the Daily News lacked pretension, no one could say it wasn’t entertaining. The paper thumbed its nose at staid journalistic tradition: its headlines blared, its front page was often exclusively photos, and its stories emphasized emotional appeal over objective observation. Like the British tabloids it copied, the News was half the size of traditional papers, yet its circulation quickly grew far larger. By the mid 1920s the News had the largest daily circulation of any paper in New York City, at seven hundred fifty thousand; in fact, its circulation would be the largest in the country until the late 1940s.

Where the Graphic had dismissed any concern for journalistic propriety, the Daily News walked to the edge without jumping off. Its coverage could be sensational, even lurid, but it could not be fabricated. Patterson’s guideline was “no private scandal or private love affairs,” though if they became public through divorce proceedings they were fair game. Patterson understood the power of celebrity news and so nurtured a stable of gossip reporters. As Ed joined the paper, it already had two established show business columnists, John Chapman and Sidney Skolsky.

Although Sullivan had blasted his competitors as he launched his Graphic column, decrying the moral turpitude of the veteran gossips, he launched his Daily News column as an incumbent. As he began his News column in mid July—just two weeks after the Graphic folded—he made no grand proclamations, he simply went back to work chronicling Broadway life. His salary was $200 a week, a sharp step down from the Graphic’s $375 but a highly desirable paycheck nonetheless. He began with three columns a week, which put him in a kind of probation status; many Broadway scribes turned out a daily column as he had at the Graphic.

While his debut featured no grand announcements, his new column displayed a markedly different attitude. Ed’s new approach would not be as colorful or as free as it had been at the Graphic; there would be no more half-page descriptions of gypsy girls at stoplights and no philosophic meanderings about mob slayings. He was now a coolheaded, evenhanded veteran, like his colleagues Skolsky and Chapman.

More significantly, he was now an unabashed populist. At the Graphic he had written only periodically about the Depression and the struggles of the common folk; primarily his column had been a window into the lives of the swank set, even as his theme of their essential unhappiness pulled away the curtain. At the News he would still cover this half-mythic world. His column was full of stories about people like actress Peggy Hopkins Joyce, whose “only drink was champagne” and who went out on the town in a $3,000 ermine coverlet. As he churned out tidbits about actors, singers, cabaret stars, and well-to-do socialites—their dizzying round-robin of romance rotating faster than their nightclub of choice—the portrait could transport the average reader to a fabulous world.

But getting much more weight were the average people themselves. His writing now focused on and celebrated—empathized with—the life of the common man. As a freshman Broadway columnist he had been a fabulist with a touch of populism; now the populism came first. The shift was in keeping with the times, and with his new employer. The Graphic had embraced the giddy, no-tomorrow 1920s; the Daily News, sometimes called a newspaper that wore overalls, was an archetypical representative of the populism of the 1930s.

Soon after beginning his News column, Ed wrote about the phrase “You can’t do that to me,” and how often it expresses desperation. “All the ache and hurt that can be summoned is compressed into these six words,” he wrote. “The labor and work of a lifetime is about to be swept away as a veteran employee is dismissed from a business office. He wants to cry out that he has children at home to be fed and clothed … But his heart has stopped beating its normal tempo … and he can utter only six words: ‘You can’t do that to me.’ ” Ed incorporated this vox populi theme in his gossip blurbs by reporting the romances of people like Artie Cohen, a Broadway tailor who eloped with his bride to Rye, New York.

And Sullivan seemingly never passed up the chance to include items like those that chastised the “nationally-known comic [who] chiseled $2.50 from the pay of $7.50-a-day extras on the local Warner lot.” He tweaked actor Charlie Winniger, then starring on Broadway, because “his refusal to cut his “Show Boat” salary from $1,000 a week to $750 a week may throw 230 people out of work.”

His anecdotes were now more often about life outside the world of affluence:

“Overhead the L trains rattled and jolted along, between grimy buildings … On the street surface, cars honked impatiently and tense-faced traffic cops, nearing the end of a wearying tour, signaled curtly … In front of a restaurant, two derelicts feasted their eyes on the day’s menu, as if unable to tear their eyes from it. I thought to myself, ‘Here is the very essence of this huge city of ours’ and turned to go, almost colliding with a tall mendicant, his face coarsened by a two-day stubble of beard … ‘Cowboy songs, Mister?’ he said … ‘Get the songs of the open range, 5 cents’…Overhead the L trains rattled as I paid him his modest fee … ‘Songs of the Open Range’ … On Third Ave. and 42nd Street.”

It’s likely that Ed’s populism came to him naturally, but it was also an effective competitive strategy for a columnist in a crowded field. It set him apart from many of his competitors, like the News’ Sidney Skolsky, who would no sooner report the elopement of a tailor than print a Sunday school prayer. By playing to his audience, mingling mentions of the hoi polloi with the illuminati, Ed curried favor with those readers who could never hope to sip a champagne cocktail, which was most of them. He was an anti-elitist covering the elite.

But hard-pressed average readers also wanted release from the daily grind, and Ed gave it to them. These readers turned to Broadway columns for the same reason they flipped on a radio: to be transported, to enter a fantasy world. Ed was their membership card to an exclusive club, a fantastic world sometimes referred to as “café society.”

![]()

The milieu known loosely as café society was a glittering alloy of screen and stage performers, radio personalities, star athletes, debutantes, musicians, old money socialites, press agents, promoters, and producers: those who were talented and those who wanted to associate with the talented. Despite the Depression, café society rubbed elbows nightly in 1930s Manhattan. Its gathering places were nightclubs like the Colony, El Morocco, Dave’s Blue Room, the Hollywood, and—foremost—the Stork Club, nightspots where entrance alone—if you could get past the doorman—would set you back $5 or even $10.

This gathering of the beautiful and the lucky was a living incarnation of what moviegoers paid two dimes to see on-screen in the 1930s: cool glamour, light conversation attended by chilled champagne, and romances begun while fox-trotting to elegant orchestra music. That right outside the door the unemployment rate was twenty-five percent made this privileged party seem closer to dreamscape than reality.

Being a star in this world meant getting noticed, being one of those that others mentioned when they talked about their evening at Lindy’s or Jimmy Kelly’s. One of the best ways to do this was to appear, as frequently as possible, in Broadway’s leading gossip columns. In an era before television, these columns had inordinate power on the celebrity social scene. To rate a boldface tidbit in the pages of the Daily News, the Post, or the Daily Mirror meant you were a somebody, you existed, that others would turn their heads as you walked in. Ed, as a columnist for the News—far above the ever-shaky Graphic—was now the ultimate insider in this scene. His News berth made him a player, someone whose opinion was talked about and sought after, a leading social arbiter of café society.

The job allowed him to live in his natural habitat. Ed was a nightly sight at Broadway’s openings and ritzy watering holes, dressed in a tailored double-breasted suit, cigarette in hand, hair slicked straight back, socializing with an ever-expanding network of performers, politicos, socialites, and athletes. A magazine profile from the mid 1930s described him: “He seldom gets home before five a.m., in the meanwhile having taken in, on a typical night, ‘21,’ the Stork Club, the Hollywood, Dave’s Blue Room, Lindy’s, and Jimmy Kelly’s.… Courvoisier brandy is his only but not single drink; then it’s bed until one or two in the afternoon. The column is written—at home. That takes a couple of hours and Sullivan then drives down to the Daily News, reads his mail, and waits while the composing room gives him a proof.”

Central to his column were the vagaries of love among the smart set, the intoxicating sexual merry-go-round of Broadway romance:

“Take, for instance, slender and blonde June Knight … her affairs of the heart have kept my operatives working in double shifts since she arrived here to “hot cha” for Ziegfeld … First it was Elliot Myer … Then it was Elliot Sperber … Succeeded by Leo Friede … Who, in turn gave way to Sailing Baruch, Jr.,… Neil Andrews stepped in when Baruch stepped out … Now it looks as though Tommy Manville, Jr., is the lucky guy.”

Ed reported on a mythic group of people who had been liberated from the staid sexual mores of Victorian America. The 1920s had seen a revolution in morals and manners. Women, having picketed the White House and gotten hauled away in paddy wagons, had won the right to vote. Hemlines inched up and young ladies went out on the town by themselves. In 1926, Mae West premiered her play Sex, which scandalized the public with tunes like “Honey, Let Yo’ Drawers Hang Low”—and scored a box office bonanza. And though hemlines had fallen with the crash, something had been loosened by that giddy decade, and Ed’s column covered the results. He dished out a heady catalog of morsels like “Phil Baker, the only bird who can make love over the top of an accordion” and “Maurice Chevalier, who’d rather go places with his pal Primo Camera, than make love to Jeanette MacDonald.…” Printing material like this would have been forbidden not that many years previously—and would seem merely quaint a few decades hence—but it sold newspapers in the 1930s.

Ed’s reports of the rapid pace of modern love, which in his column seemed to twirl faster than ever, offered readers a vicarious thrill. “Romances fizzle and burn out in a hurry on the Queerialto that is tagged Broadway … the big heart affairs pass into the hands of receivers quicker than that,” he reported. (Sullivan invented his own slang term for Broadway, “Queerialto,” a combination of “queer”—he always found the Broadway world odd—and “Rialto,” after the famous Broadway theater.) If he could fit in a bit of moralizing with his coverage of romance, all the better:

“Funny, the reactions of the fellows who are involved in these affairs of the cardiac … Tommy Manville, Jr., heir to the asbestos millions … is typical of the wealthier playboys of the Main Stem … Interested in the lovelies of the stage, Manville, like his fellows, will go just so far … The breaking point arrives when a column like this reports that Manville is thinking of buying an engagement ring … The current romance is dead the following day … to the wealthy fellows, wedding bells make a noise like a police riot car.”

The News gave Sullivan wide latitude in terms of what he covered, and, like his TV show in later years, his column offered something for many audiences: romantic travails, theater news, political predictions, show business gossip, odd quotes that celebrities gave him, and bits of shopworn wisdom. It was all jumbled together without any differentiation, a stream of consciousness Broadway diary, like the circuitous route taken by a cabbie trolling all of Manhattan. On a daily basis he veered from wedding news, denoted as “hunting for a license bureau,” to announcing a starlet’s pregnancy, referred to as “the arrival of Sir Stork,” to alimony payments, all within the space of a single paragraph.

As at the Graphic, he rarely wrote detailed theater criticism, but he often passed pithy one-line judgment on new Broadway shows (which, if positive, were used in a show’s advertisements). “By far the smartest premiere of the winter season … Was the inaugural performance of Design for Living, featuring Noël Coward, Alfred Lunt, and Lynn Fontanne,” he opined. But even in these hit-and-run reviews he usually spent more ink on the evening’s social scene than on the dramaturgy.

In the Coward opening, he went on to list many of the well-heeled theater patrons in the audience. “Coward’s play delights this audience of the elite … it is as light as champagne bubbles, and produces the same gayety … You leave the theatre and mounted cops are holding back the curious sidewalk onlookers … There is a double line of cars in West 47th street, waiting for their mesdames and messieurs … Most of them are Rolls Royces … it was that kind of opening,” Ed observed, displaying, as he often did, his sense of being a reporter looking at the privileged from afar.

One of his column’s constants were bite-sized descriptions of famous people, opinionated portraits of those with whom he rubbed elbows. He would string together a number of these, as if bringing the reader to an exclusive Broadway party.

“Jack Benny, stage, radio, and movie comedian … Sleepiest of all Broadway personalities … He invites 20 people to 55 Central Park West, and then curls up on the living room couch and goes to sleep … On the level … If he could learn to sleep standing up, he’d make a fine cop … Estelle Taylor, ex-frau of ex-champ Dempsey … one of the keenest wits I’ve ever encountered … With a marvelous sense of humor that bewilders plenty of Coast dumbbells … [actress] Lupe Velez, madcap of movieland … Whose 70 coats, 230 dresses, and 126 pairs of shoes don’t mean a thing because she bought them only for ONE man … And then Gary Cooper wasn’t the fellow she thought he was.”

When he couldn’t actually be present he relied, as always, on his citywide network of sources developed while at the Graphic. They allowed him to report that Jimmy Cagney was in town and “secretly registered” at the Wellington Hotel, or that the Hollywood party thrown for George Burns and Gracie Allen featured some odd sights: “On the way to the dining room, a naked fellow, sitting in a tub of water, hailed the guests as they passed the door, and advised them not to eat, as the food was terrible.”

Sullivan was quick to trumpet any tidbits he scooped his competitors on, however reliable the scoop might be. “Months before Wild Bill Donovan forced his recognition as a gubernatorial candidate, the news was printed in this column … A week before Jimmy Walker resigned, my Monday column predicted it.” (In truth, predicting the forced resignation of the embattled mayor, known as the “Night Mayor” for his fondness for the high life, was hardly prescient; at any rate, a few months earlier Ed had predicted Walker would be cleared.)

“The information I got late last night … is loaded with political dynamite,” he wrote in October 1932, three weeks before the election that sent Franklin Roosevelt to the White House. “One who is in the know named for me the cabinet which he says Franklin D. Roosevelt plans to install at Washington … and it is SOME combination.” Ed listed eight members of the potential FDR cabinet, only one of whom became an actual cabinet member. In the early days of the Roosevelt administration, Ed was boundless in his support of the new president, as was the Daily News itself. In April 1933, he enthused: “Hugest individual hit of the season, Franklin Delano Roosevelt!!!”

True to the ethic of the Broadway columnist, Ed’s scoops were sometimes more timely than accurate. But that was the nature of this new brand of journalism. (The New York Post would later print page after page of Walter Winchell’s mistakes, his so-called “wrongoes.”) The Broadway column was less about authoritative news than it was the diary of a community, an ephemeral compilation of what the Manhattan tribe was chattering and whispering about. The writings of the Broadway columnists from this period were riddled with factual inaccuracies, half-truths, conjecture, and the alcohol-fueled imaginings born of typing against a 5:30 A.M. deadline. But while these columnists, Sullivan among them, provoked a public outcry from those who called them a moral corruption, their readers didn’t seem to care. The world that Ed was writing about was hungry for coverage, and those on the outside looking in were even hungrier for the details.

![]()

Sullivan’s unstinting dedication to his column left little time for home life. Replacing the domestic scene was a blur of Manhattan nightspots. Several months after landing his Daily News post he wrote about his recent nocturnal jaunt with Freeman Gosden and Charlie Correll, stars of the Amos ’n’ Andy radio show, then listened to by tens of millions of fans weekly. “I left them at 5 A.M., and I was pale and haggard,” he wrote. “Dave Marks, the toy millionaire, was in equally bad condition … ‘You’re not going home, Ed?’ Gosden queried reproachfully … I assured him that I was going home … ‘That’s too bad,’ said Correll, ‘we thought that as it’s only 5 A.M., we could go to Place Pigalle and then taper off with a cup of coffee.’ ” Being out all night was an occupational hazard for the columnist.

But Ed never missed home life. He seemed to take little interest in it. As recalled by his grandson Rob Precht, Ed found the concept of family life to be greatly overrated. He did, however, continue to take Sylvia out to dinner almost every night, as when they were courting. Sylvia was invariably elegantly dressed—she loved to go out—and the two made the rounds of New York’s fashionable restaurants; this also allowed Ed to continue his society reporting. Sylvia never learned to cook and never had the slightest desire to do so. Eventually the couple would move into an apartment with hardly any kitchen at all. As their daughter Betty recalled, “My parents never ate at home. My father liked to be able to choose what he wanted to eat. I don’t think he was that thrilled about eating.”

Betty herself was cared for by a paid companion during Ed and Sylvia’s evenings out. “When I was about two years old, my parents took me to Saratoga [in New York] to see the races. I was a very little girl, and I banged with my feet on the bottom of the table,” she remembered. “And my father was so distressed, embarrassed, that I really don’t think I went out with them until I was twelve. Until I could act like a young adult.” Her companion took her to eat at a succession of Manhattan restaurants, though Betty chose less formal places than those frequented by her parents.

As Ed took little time for home life, he also found little time for close friendships. In his twenties he had sought the companionship of boxer Johnny Dundee and soft-shoe dancer Lou Clayton, both largely as mentors. But while he now traveled a social circle as large as the Manhattan phone book, he was close with virtually no one. The sole exception was Joe Moore, the former speed skating star who was now a press agent, and whose friendship with Ed made him a conduit to Sullivan’s column. But even this was as much professional as personal. Having close friends “wasn’t in his nature,” recalled his daughter.

![]()

Covering the famous only whetted Ed’s appetite to be famous himself. His Daily News column greatly increased his profile but didn’t satisfy this core desire. That he was now a Broadway somebody only made the question more urgent: how could he turn himself from a reporter into somebody who was reported on? His first attempt at radio had been canceled, but in 1933 he found a far more intriguing opportunity: the movies. Or rather, he didn’t find the opportunity, he created it. Sullivan conceived of and wrote a film script, featuring himself as the star, called Mr. Broadway. He convinced a film laboratory and a large New York optical house to back the movie. To help him, Ed hired Edgar G. Ulmer, who later became a leading B movie director, and actor Johnnie Walker, who had starred in scores of silent movies.

Mr. Broadway was a two-part film, with the first part a cinematic portrayal of the columnist’s life as he made his rounds every night, and the second part a short melodrama. At the opening of the fifty-nine-minute movie, Ed introduces himself, then tours three of Manhattan’s busiest nightspots, the Hollywood, the Casino, and the Paradise. Along the way he talks with, or watches the performances of, a glittering galaxy of celebrities: Jack Benny and Mary Livingston, actor Bert Lahr, vocalist Ruth Etting, dancer Hal LeRoy, vaudevillians Benny Fields and Blossom Seeley, bandleaders Eddie Duchin and Abe Lyman, and boxers Jack Dempsey, Maxie Rosenbloom, and Primo Camera.

At about the film’s forty-five-minute mark, Ed confides that there’s a broken heart for every broken light on Broadway, reprising the theme of “unhappiness despite stardom” that ran throughout his Graphic column. At this point the film turns into an overheated melodrama about a young woman, her two suitors, and a stolen necklace. The director, Ulmer, later said he “didn’t like it at all, because Sullivan forced it into one of these moonlight-and-pretzel things. It was a nightmare, a mixture of all kinds of styles.”

On the town, 1935: As a gossip columnist with a daily column to fill, Sullivan circulated through Manhattan’s Café Society nearly every night of the week. Here he is at the Versailles Club with, from right, his wife Sylvia, Ziegfeld Follies performer Mary Alice Rice, and silent screen star Conrad Nagel. (New York Daily News)

Reviewers agreed. “There is nothing particularly new or entertaining in all this unless one happens to be the type that enjoys glimpsing the near greats at play,” sniffed The New York Times, which pronounced the story element “unintentional burlesque.” Variety found the nightclub tour interesting but judged the movie unsatisfactory overall: “As entertainment, it fails to measure up.” The low-budget production was “many leagues behind the average as to story, action, direction, photography.” As for Ed’s soap opera at the film’s end, “The meller [melodrama] sequence to which [the] film cuts in telling the story is very amateurishly carried out.… It shows how a man murders his best friend to please a girl whom he later learns is a prostie.”

Although the movie was roundly panned, Ed tried again in 1934 with Ed Sullivan’s Headliners. This twenty-minute short was directed by Milton Schwarzwald, who directed dozens of 1930s musical-comedy shorts; the film’s music was supervised by Sylvia Fine, a composer who later wrote some sharp material for singer-actor Danny Kaye, her husband. The short, again, was a collection of appearances by Broadway’s leading lights, with Sullivan as tour guide. But despite its celebrity sightings and directorial and musical talent, Headliners, like Mr. Broadway, disappeared without a trace. Because both films were made without the help of a studio, it’s likely they received limited distribution. Whatever minimal success they might have had, they failed in their primary goal: to launch Ed in a film career. Nevertheless, he wasn’t giving up.

![]()

After being hired by the Daily News in 1932 to write three columns a week, by early 1933 the paper promoted Sullivan to full status, with five Broadway columns weekly. He had made it on the Main Stem. As if to prove he was a force to be reckoned with, he began the year by picking a fight with no less a star than Eddie Cantor.

Having grown up in Yiddish theater, Cantor sang and joked his way to vaudeville’s pinnacle, topping it off by winning a role in Ziegfeld’s Midnight Frolics revue in 1916. His physical comedy fueled a passel of wildly popular silent films through the 1920s. Soon after the advent of talkies in 1927, Samuel Goldwyn hired him to croon, mug, and dance in a string of lavishly produced musical comedies. By 1933 Cantor was one the country’s most admired celebrities.

Sullivan, in a column segment called “Cantor Goes to Dogs,” claimed that the performer had stolen the comic dog routine of vaudevillian Bert Lahr. Worse, he compared Cantor to Milton Berle, an up-and-coming comedian well-known for lifting material from other comics. “I can’t give Cantor a great deal of credit in lifting Lahr’s act,” Ed wrote. “If Broadway has been intolerant of Milton Berle, a youngster, it should be doubly of Cantor for establishing a nasty precedent.”

Cantor, enraged, phoned Sullivan and cursed at him vehemently. In a follow-up column, Ed made sport of the conflict, recounting Cantor’s anger as a source of amusement. He described the performer’s verbal tongue lashing with typographical discretion:

1:04 A.M.—“Hello, Ed, this is Eddie Cantor. I just read that story and I want to tell you something.… I never had anything to do with those *!*”!* dogs!…”

1:05 A.M. (Sullivan) “Now wait a min-”

1:05¼ A.M. Cantor—“No, let me finish.… In the first place I’m not doing the dog act, Jessel’s doing it.… I don’t need those *!*”! dogs in my act.…”

It turned out that Sullivan’s claims of plagiarism were inaccurate. But Ed, characteristically, admitted no mistake. Instead he obfuscated, conceding that another producer had indeed been responsible, yet noting that the theatrical theft occurred in Cantor’s revue. At the skirmish’s end he threw one last column jab at the popular performer: “I suggest Cantor urge Jessel to drop Lahr’s dog act. That would do more to discourage theatrical banditti than any preaching in this space.”

The point Ed was making, really, was that he was now big enough to tweak a Broadway heavyweight. Just nineteen months before he had been a sports columnist, but now he was scolding one of the Main Stem’s top names, a star with an adoring national following. He had arrived.

Furthermore, his minor tussle with Cantor was Ed at his most natural: in conflict. As in the athletic fields of Port Chester, he always dove in headfirst, never backing down and never fearing the resultant split lip. For him conflict was as comfortable as breathing. And, it was good for the column. In tweaking Cantor, Ed was doing what Broadway columnists did. They engaged in arguments; they fought, bickered, and had spats with whomever was at hand, regardless of the merits of the case. It was a reliable way to keep their column a topic of conversation, and to ensure people turned to it shortly after glancing at the front page.

Toward the end of 1934, Ed combined his taste for journalistic fisticuffs with his populist instincts. As Christmas approached he used his column to write an open letter to Barbara Hutton, heiress to the massive Wool worth fortune. In the popular imagination Hutton was a cipher for easy wealth and the high life. At age four her mother had committed suicide, leading the tabloids to dub Hutton the “Poor Little Rich Girl.” In 1933, at age twenty-one, she inherited the $50 million Woolworth estate. She was then married to her first of seven husbands, Russian-born Prince Mdivani, commonly thought of as a society playboy.

Ed wrote Hutton a holiday request. “How about establishing an annual Princess Barbara Christmas Dinner for some of the poor of New York City?” he asked, suggesting she donate one thousand Christmas baskets to charity.

The item was characteristic of Ed’s writing, which played to his Depression-worn readers while reporting on the glittering set. But Ed didn’t stop with his request. He went on to give Hutton, and especially her husband, a journalistic thrashing:

“The unreality of your existence must be boring, Princess. You have a husband who has little or no relation to everyday life … I have heard grim and resolute men say some nasty things about your husband … I have heard underworld chieftains speak about him and his apparently callous disregard for human suffering, and I would not want them to speak that way about me.”

The article’s arm-twisting request for money was decried by, among others, a writer in The New Yorker magazine’s “Talk of the Town” section, who opined, “We think the time has come for someone to do something about the Broadway columnists who write open letters to people for money.” Hutton, seeking defense from the full-bore fusillade—she called it blackmail—sought the help of Walter Winchell. Winchell eagerly took up battle against his Newscounterpart, firing a return volley in his Daily Mirror column:

“We endorse anybody who helps the poor, but that’s beside the argument … The open-letter sender took pains to point out that her husband wasn’t popular with the gang chiefs ‘who would like to meet him on some waterfront.’ A remark, incidentally that some of the ‘boys’ resented … we subscribe to the sentiment of many who considered the article in the ugliest taste … and we pledge them all, that every time anybody uses (or abuses) a newspaper in that manner, we’ll fight it and protest against it at the top of our lungs and typewriter … That means YOU!”

But Sullivan’s strong-arm tactic prevailed. One week before Christmas a $5,000 check arrived from Hutton. And Ed, in his manner, thanked her. He wrote an open letter to New York’s children, describing the many letters he had received from needy parents:

“There’s one letter from one of your mothers, and it is typical … She says that the three of you had chopped meat for Thanksgiving, and the older boy said: ‘Mamma, why aren’t you and papa eating?’ … She told you that she and your dad had eaten earlier and that they weren’t hungry, but listen, you three little kids … Your mother and father were fibbing … When you grow up, I want you to be pretty swell to them. [These parents don’t ask for much,] just enough to stuff small stomachs on Christmas Day … it seems to me that in the richest city in the world, that is a reasonable request. A very lovely lady, who doesn’t want her name used, thinks that it is a reasonable request, too … she’s the kind of lady you read about in story books … She sent me a check for $5,000.”

Although Ed had achieved his goal, the incident marked a new season in his relationship with Walter Winchell. They would now be archrivals.

It hadn’t always been so. There was a period after Sullivan took over Winchell’s former spot at the Graphic that it looked as if the two, while professional rivals, might have something of a friendship. Walter had called Ed about the CBS radio opening, and Ed had sent Walter a series of affectionate notes. “Your Monday column still fills me with respectful amazement,” he wrote in one missive to Walter. “It’s gorgeous great. Where you get it, I don’t know but as I pay better dough, I believe your operatives, with the possible exception of Dorothy Parker, will see the error of their ways and get on the Sullivan bandwagon.”

After Winchell got into a contretemps at the Casino Park Hotel, in which stage producer Earl Carroll told him he wasn’t “fit to be with decent people” because of his brand of gossip, and Winchell had stood his ground—the incident became the talk of Broadway—Ed dashed him off a lighthearted memo: “If you let me know who’s fighting at the Casino next week I would like to make my reservations in advance.” Even after Ed moved to the Daily News, establishing himself in a secure post, he sent Walter a note combining flattery with affectionate chiding. A recent Winchell radio show, Sullivan opined in his letter, hadn’t lived up to the quality of Walter’s column; however, Ed confided, “you are the only one for whom I hold a sincere personal and professional respect.” When Walter’s nine-year-old daughter Gloria died on Christmas Eve of 1932, Ed and Sylvia sent a condolence note. But by 1934 their relationship had changed. Ed was no longer a freshman columnist, and any need to curry favor with an upperclassman was gone. They would henceforth only snarl at one another.

![]()

An element in Ed’s column that was as constant as conflict was his appreciation of female pulchritude. An attractive woman was “an eyeful,” and he used the phrase frequently. The avenues of Manhattan were chock-full of such creatures, by Sullivan’s account. In a typical column, he wrote about spending the evening at a Greenwich Village nightclub owned by Barney Gallant. “The other night, sitting in the half-gloom of the place … I asked him the one question he has always avoided … I asked him who, in his opinion, was the most gorgeous woman he’d ever seen.”

To further investigate New York beauty, he assembled an “All-American, All-Gal Eleven,” a mock all-star football team of female performers:

“Picking the first team, my All-American, All-Gal Eleven, was no part of a cinch … I spent a small fortune taking out each of the candidates, feeding ’em, and noting their reactions.

“In the course of my selections, I had to drop at least twenty girls for one reason or another. I had Peggy Joyce lined up for quarterback, but when she insisted on magnums of champagne for the training table I had to let her go. Claire Carter was ideal for tackle and she would have added blonde charm to the forward wall, but she wouldn’t leave Jay C. Flippen for practice.”

Not all of the women were picked because they were an eyeful. Gracie Allen, who played a ditzy counterpart to George Burns’ straight man, was chosen as quarterback for her ability to confuse the defense. Aunt Jemima, a heavyset vaudeville singer later memorialized as the advertising icon for a pancake syrup, was selected for her heft.

A few weeks later, Ed assembled a corresponding men’s Broadway all-star team, but he gave it short shrift by comparison, and apparently felt it unnecessary to take each man to dinner.

![]()

In the fall of 1933, Ed’s high profile as a Daily News columnist led to a series of invitations to produce and host charity shows. In November he organized and emceed an all-black show for the Urban League benefit at Manhattan’s Town Hall, presenting tap dancer Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, singing quartet the Southernaires, and the Nicholas Brothers, a two-brother vaudeville tap dance team. The following evening he emceed a revue he produced for the Jewish Philanthropic Societies, held at the Waldorf-Astoria hotel, featuring a raft of radio and stage stars.

At the end of November he walked onstage for an event that would mark the beginning of a life-long career: his first variety show.

The manager of Manhattan’s Paramount Theatre, Boris Morros, invited him to produce and host the show. The phone call from Morros became a favorite anecdote of Ed’s, though it appears to be an exaggeration. Morros called Sullivan to offer him $1,000 for a one-week run; for this fee, Ed would choose and pay the performers, taking the remaining money for himself. Ed—overjoyed by the lucrative offer—said, “You must be crazy.” In Sullivan’s telling, Morros thought the columnist was negotiating and so quickly raised the offer to $1,500. They went back and forth like this, and by the end of the day Morros agreed to pay him $3,750, according to Sullivan. It’s highly unlikely that a theater manager in the depth of the Depression would almost quadruple his offer based on a simple misunderstanding. But the anecdote portrays Ed as highly sought after, and he loved to repeat it. Whatever the actual negotiation process, he readily agreed.

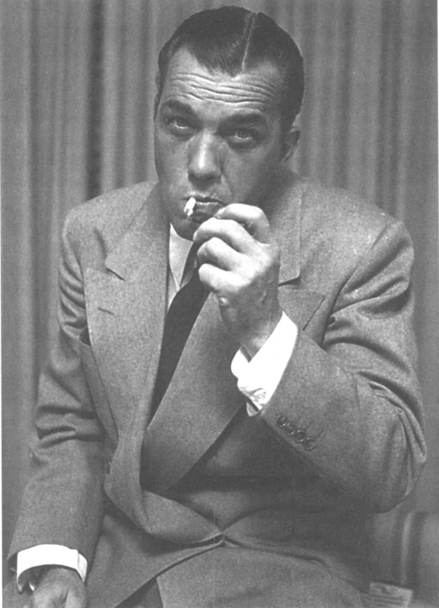

Broadway tough guy: although he would later present himself as the staid guardian of the American living room, Sullivan came of age in the rough-and-tumble of the 1920s New York newspaper business. This 1954 photo reveals the streetwise side of the showman. (Globe Photos)

To organize the show, he relied on a format with a rich tradition: vaudeville. By the early 1930s classic vaudeville was on its last legs. The Depression meant there were fewer people with an extra dime, and movies and radio were offering overwhelming competition. After the first talkie in 1927 the allure of moving pictures had proven irresistible, and radio brought theater into listeners’ homes for free. As Ed had written in 1932, “No longer does an actor boast of playing ten weeks at the Palace … Now they’re interested only in how many stations they’re on.” Vaudeville had grown stale and dated as many veteran acts offered the same routine year after year. Yet the American taste for the new and different had continued apace, the Depression notwithstanding. Forward-looking social commentators in the early 1930s were writing nostalgic eulogies for vaudeville.

Although vaudeville circuits were closing, the form’s guiding principles would live on; its roots ran too deep to disappear. Borne of the English music hall, Yiddish theater, and the traveling minstrel show, vaudeville had come into its own in America in the 1880s and had flourished for decades. Several generations of American performers grew up on its stage, including Bob Hope, Jack Benny, Al Jolson, Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, W.C. Fields, Mae West, Will Rogers, Ethel Waters, Jimmy Cagney, Bessie Smith, Bums and Allen, Fred Astaire, Gene Kelly, Sammy Davis, Jr., and the Marx Brothers.

Ethnic distinctions were very pronounced in vaudeville. Irish, Italian, and Jewish performers played their routines according to the broad stereotypes associated with these groups. Present in almost all shows was a blackface act, typically a white performer whose face was blackened with burned cork, affecting a dialect and playing the role of a happy-go-lucky shiftless black man for laughs. The crude caricature of blackface routines was a facet of vaudeville that appeared most dated by the 1930s.

A vaudeville show moved at a relentless tempo, with a blink-and-you-miss-it succession of one-legged tap dancers, comics, ventriloquists, blackface song and dance acts, legitimate musical theater, jugglers, acrobats, and one-liner artists, all pushed along by a master of ceremonies who kept things moving—briskly, at all times. If you didn’t like a routine there was no time to get bored; you’d soon see a new one.

If people enjoyed watching it, an act usually found its way to vaudeville. The Mayo Brothers did a two-man dance-acrobatics routine on a small tabletop. One popular performer was a skilled regurgitator who swallowed live fish and brought them back up at will. Jack Spoons lifted chairs with his teeth while he played the spoons, and Joe Frisco smoked a cigar while doing soft-shoe. Lady Alice balanced trained rats on both arms, with a rodent on top of her head that was trained to blow into a kazoo. Fuzzy Night and his Little Piano featured a man who danced with his piano.

The audience felt that their 10-cent ticket gave them the right to participate as much as the performers. The hecklers and “gallery gods,” as vocal audience members were known, voiced their opinion with full-throated freedom, letting fly with a thin shower of coins or last week’s leftover produce. If the jeers of the gallery gods pronounced an act unworthy, a large hook pulled the performer offstage.

Vaudeville’s core principle was offering something for everyone. The businessmen who ran the major circuits, most notably Benjamin Keith and Edward Albee, knew that an all-inclusive philosophy drew the biggest audience. A single show might offer the likes of Mae West making the men roar with pleasure at her risqué “shimmy” dances; a well-muscled and shirtless Man of Steel providing male pulchritude for the ladies; for recent émigrés, Benny Rubin telling funny stories in Yiddish dialect and Maggie Cline, the “Irish Queen,” belting out Throw Him Down, McCloskey; the Nicholas Brothers, two young black boys in elegant suits, dancing a dazzling tap routine; and Poodles Hanneford playing the slapstick clown. Vaudeville was the great wellspring of American entertainment, the heterogeneous offering of every voice. All of its acts existed side by side in a show business melting pot, exposing all the audience members to the dissimilar tastes of their seatmates. The performers, too, experienced cross-cultural pollination, as acts reached across ethnic divisions to steal the comic or musical inventions of their competitors.

Something for everyone, and everyone was invited: the credo of the Keith-Albee circuit was family entertainment. Vaudeville houses had been bawdy places, but under Keith and Albee’s iron-fisted control the shows were cleaned up. It was good for business. The use of vulgarity onstage was strictly prohibited under threat of instant dismissal. Benjamin Keith once advertised that he employed a Sunday school teacher at rehearsals to ensure propriety—though vaudeville shows were earthier than that suggests. But certainly the whole family could attend, kids and all.

Part of vaudeville’s “something for everyone” formula was appealing to the local tastes of the city the show found itself in. Local jokes were inserted into stock skits and a burg’s major ethnic groups were played to. Nowhere was this big tent approach as complex and cacophonous as in New York City. With its divergent immigrant population, satisfying New York audiences compelled producers to cater to a discordant quilt of attitudes and backgrounds. Fortunately for the city’s showmen, every performer they needed for this unlikely task was locally available. New York was vaudeville’s heart, its mecca that all vaudevillians dreamed of.

The Olympian pinnacle of New York vaudeville was the Palace, at Broadway and 47th Street. Just thinking about the Palace brought a faraway gleam to a performer’s eye. In 1919 its brightest stars were commanding the heavenly salary of $2,500 a week. In the late 1920s, Eddie Cantor made $7,700 a week. However, by the early 1930s even the Palace was fading. Despite some glorious 1931 shows by Kate Smith, Sophie Tucker, and Burns and Allen, by the early 1930s it was largely a movie house.

The Paramount, where Ed produced his first show in November 1933, was also in transition. The theater was hedging its bet between film and vaudeville. For one ticket price, patrons saw both a live stage show and a Hollywood film, one following the other. This practice would become standard in New York theaters throughout the 1930s and 1940s. Sullivan’s Paramount revue, called Gems of the Town, shared the bill with the recently released musical comedy Take a Chance, starring James Dunn and June Knight. (Ed had reported on Knight’s love life in his column.)

Sullivan’s variety show at the Paramount was not classic vaudeville, though it was close. The program featured a similar up-tempo parade of fast-paced acts with an emcee as a central ringmaster. But Sullivan left out some of vaudeville’s most characteristic routines, like blackface minstrel singing and broadly ethnic acts. To headline the show he booked clown-comic Jimmy Savo, a top vaudeville star who had played the Palace in its prime; Charlie Chaplin had called him “the best pantomimist in the world.” That night at the Paramount he bounced and bounded all over the stage. The show’s reviewer, who enjoyed the show, wrote that Savo, “knows when to strike; when to efface himself; when to leave the stage altogether; and how to get the maximum effect out of a sudden, unheralded return.” Sharing the bill with Savo were two tap dancing acts, Betty Jane Cooper and the Lathrop Brothers, and an acrobatic troupe, the Uierios. Based on his other shows from this period, it’s likely that Ed added a contemporary touch to his revue: introducing celebrity athletes or performers from the audience, whom he had invited to be on hand.

In essence, Sullivan’s Paramount stint was what was then called a variety show. It was updated vaudeville, a quick-stepping stage show offering something for everyone—comedy, music, acrobatics—without the most dated acts. (The terms “variety” and “vaudeville” had been used interchangeably to describe stage shows for many years, and “vaudeville,” though the genre was declared dead, would still be used for years to come.)

Vaudeville’s near-death state probably contributed to Paramount Theatre manager Boris Morros’ decision to invite Ed to produce a show. As vaudeville withered, theater managers started using tricks like hiring columnists to produce revues. The advantage was twofold: a columnist could advertise his own show, and he could also cajole performers to appear for less by offering them publicity (or threatening to pan them). As Time magazine observed years later, “Though at war with Winchell, Ed, like a good general, learned a great deal from his enemy. Winchell emceed a stage show at Manhattan’s Paramount, using the pressure of his column to line up good acts at a nominal cost. Ed did the same and earned $3,750 for a week’s stand.”

![]()

Sullivan’s first attempt at radio had been short-lived, but in March 1934 he found another opportunity. NBC was launching Musical Airship, a half hour of dance music and show business gossip, and he leaped at the chance to be its host. In the mid 1930s radio broadcasts of dance bands held America in a semihypnotic trance. Dozens of swing orchestras like those of Paul Whiteman and Eddie Duchin played live as tens of millions of listeners fox-trotted, tangoed, and waltzed. As one reporter noted, “During a single evening twenty or thirty nationally recognized batoners hold sway.” Combining dance music with humor and witty banter was a winning format. A top radio show that season was CBS’s pairing of the Guy Lombardo Orchestra with the George Burns-Gracie Allen comedy team.

When Musical Airship debuted on March 7, it featured the Vincent Lopez Orchestra, one of the country’s leading swing outfits. Sometimes called “The Tango Terror,” Lopez had been a successful bandleader for more than a decade; over the years his bands were a way station for the likes of Glenn Miller and Tommy and Jimmy Dorsey. Sullivan had been friends with Lopez for years; it was at the bandleader’s nightclub that Ed had met Sylvia in 1926.

The show was a joint effort: Ed was master of ceremonies, introducing Lopez’s band. He interspersed the music with show business news and chatted with a celebrity guest he brought along each week. On many weeks the Lopez band was fronted by vocalist Frances Langford, an elegant chanteuse whose star soared the following year in the Hollywood film Every Night at Eight with George Raft. Also on the show was a three-man vocal group called the Three Scamps. Musical Airship was broadcast live every Wednesday at 10 P.M. from New York’s elegant St. Regis Hotel. Sponsored by Gem Razor, the show paid Ed $1,000 a week.

The program got off to an auspicious start. Radio Guide immediately made the show its “high spot selection”—its favored choice—for the 10 P.M. hour. In April it was reported that Ed’s presence on the show “has been renewed for some time to come.” In May, a Radio Guide reviewer praised Ed, though he quibbled with one of his opinions: “Ed Sullivan, who writes a mean column, and master-of-ceremonies the Wednesday evening Musical Airship (NBC) quite well, passed a counterfeit when he intimated it was odd that radio had never yet contributed to the stage—only taken away from it.”

Despite the favorable coverage, Musical Airship had trouble finding its audience. That spring it earned a C.A.B. rating of 7.3, far better than Ed’s first show, but far behind leaders like the Jack Benny Program (25.3) and the Fred Allen Program (18.5). One month after its debut Sullivan’s show was moved from 10 P.M. to 9 P.M.—a better timeslot, but directly opposite the popular Old Gold program, hosted by charismatic tenor Dick Powell. In the middle of May it was moved again, to 8 P.M., and in early June it was back at 9 P.M. Then on June 20, with little notice, Musical Airship was canceled.

Based on the results of Radio Guide’s mail-in popularity contest, the show was hardly noticed, or at least Ed’s portion never was. Vincent Lopez garnered some modest attention; among bandleaders, readers voted him toward the bottom half. That was far better than Ed. Among the one hundred twenty-two stars ranked, with Bing Crosby and Eddie Cantor at the top, and Walter Winchell in about the middle, Sullivan wasn’t rated at all. Apparently no one sent in an entry listing him as their favorite performer. Radio wasn’t turning out to be the elevator to fame that Ed had hoped for. His first show in 1932 had lasted a little more than four months; this year’s program barely made it past three.

![]()

With his broadcast career appearing fruitless, Ed turned to the stage. Churning out a column five days a week, which many Broadway scribes viewed as more than enough, left him wanting more. In May, toward the end of Musical Airship, he had produced a single vaudeville program at Brooklyn’s RKO Albee Theatre. On July 7, just two weeks after his radio cancellation, he launched his vaudeville career in earnest.

He called his revue Ed Sullivan’s Dawn Patrol. Like his first show at the Paramount the previous November, Dawn Patrol was an up-tempo vaudeville revue with a mixed bag of comedy, dance, and music. But the new show was more elaborate and showcased a more contemporary lineup. Opening at Manhattan’s Loew’s State Theatre, on the bill were ballroom dancers Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mears, vocalist Joan Abbott, tap dancer Georgie Tapps, singer-hoofer Delores Farris, acrobatic dancer Barbara Blane, and banjo player Ken Harvey. Unlike his one-week stand at the Paramount, his revues would now run regularly, with a fresh lineup of performers for every new revue. Sullivan’s stage shows jumped from theater to theater, but his chief venue was Loew’s State, whose marquee headlined the name Ed Sullivan in oversized letters on a routine basis.

His revue’s title, Dawn Patrol, was a double entendre. It referred to the popular 1930 Howard Hawks talkie, The Dawn Patrol, about daring and chivalrous World War I flying aces; it also referred to Sullivan’s own practice of club crawling until the sun came up. He often subtitled his column “Dawn Patrol” because it reported on his nocturnal wanderings, and because the phrase helped advertise his vaudeville shows.

Sullivan wore two hats in his Dawn Patrol revue, as he would throughout his career: producer and emcee. As producer, he was the show’s business manager, taking a fee from the theater then dividing it among the performers and himself as he saw fit. More important, he made Dawn Patrol’s creative choices, building the show from the ground up, deciding which acts to book, placing them in order, determining the balance between comedy and music and dance, and giving the show its pacing. He refreshed the show constantly, mixing and matching performers as he spotted new talent in nightclubs. At some point, probably not as early as 1933, he took his control of the shows a step further: he decided which material performers would present, choosing their songs, making decisions about dance numbers, and editing the comics’ jokes. Standing right offstage as the show ran, he was its chief critic. He monitored each revue act by act, making changes based on his sense of the crowd’s response. Innumerable hours spent watching his stage shows and gauging audience response would be an invaluable education.

In contrast to his role as producer, his role as emcee—while much more visible to the public—was relatively insignificant. He simply ushered acts on and off the stage, building up the act beforehand and leading the audience in applause afterward. In fact, in his earliest shows he chose not to be master of ceremonies. Instead he hired Harry Rose, known as the “Broadway Jester,” to keep the show moving. After Rose began as emcee, there appears to be a period in which they shared hosting duties. Only after about a year of producing Dawn Patrol, when it was highly successful, did Ed make himself its master of ceremonies.

Ed’s career as a vaudeville producer-emcee demanded a grueling pace. Like many theaters, Loew’s State offered patrons a stage show and a movie for a single ticket. The double bill started in late morning and repeated itself, back to back, until after midnight, sometimes until 3 A.M. The greasepaint and sweat stayed on all day long. It was no wonder that many vaudeville performers brought their children into their act; the family lived at the theater. But as demanding as it was for performers, for the audience it was joy. As in traditional vaudeville theaters, some audience members bought a ticket in early afternoon and stayed all day—the Depression meant they could afford little else. (Some vaudeville producers placed a heinously bad act at the show’s end in an attempt to clear the theater.)

The vaudeville audience of the 1930s was a tough crowd. While more restrained than their recent forebears, who hurled rotten produce, people heckled mercilessly, and they wouldn’t clap or laugh out of polite protocol. Nor would they return to a revue if they weren’t getting their hard-earned 10 cents’ worth. A few years later Ed wrote about an attempt at humor in one of his shows. Eleanor Powell, a tap dancer, stood in front of the stage curtain and announced that she would reveal what happened when famed card manipulator Cardini played poker with the cast. The curtain opened to show Cardini losing everything but his dress shirt to a group of poker players. The audience “sat in complete silence … not even a murmur,” Ed wrote. It was a rigorous education for a showman. Pleasing this audience was like running a race carrying a forty-pound weight; if you could survive in these conditions you would likely be in good shape anywhere. And competition was fierce. Within a few blocks of Loew’s State in midtown Manhattan there was a plethora of such shows competing for their customers’ limited pocket change.

Ed’s motivation for mounting variety shows was partially money. His $200 a week Daily News salary was more than comfortable, yet his notoriety from his column made being a stage producer a lucrative second job. As a variety show producer with a well-known name he could command a large sum; anything left over after paying performers was his. And singers and dancers, with the incentive of his column mentions, could be cajoled to appear in Dawn Patrol revues at a competitive rate. As the shows became ever more successful, it’s likely that Sullivan made still more.

In addition to the money was the magnetic draw of being star of the show, center stage, with his name up in lights. Even after his television career made him wealthy, he found a way to get onstage or in front of a camera again and again. In the mid 1950s, then the producer of a hugely successful TV program, he acted in a summer stock production for fun. And in that same period he launched a live vaudeville tour of the country. He would not—could not—stay away from the spotlight. Once he debuted his Dawn Patrol revue in 1934 he was onstage constantly until almost the very end of his life.

![]()

Although he called the shows vaudeville, they owed as much to the New York nightclub as to the Keith—Albee circuit. As a denizen of Manhattan’s nightspots, that was where Ed found his talent and earned his show business education. He played up the nightclub element in his shows, dubbing some versions the “All-Star All-American Nightclub Revue.” A reviewer in 1934 noted that Sullivan offered “a variety of singers, dancers, and comics from the night clubs,” and three years later, another observed, “In customary fashion, the production has a nightclub setting, is brilliantly lighted and well-staged.” That the shows drew talent from the city’s cabarets and nightclubs meant that they were more contemporary and more urban than traditional vaudeville. (Though, of course, the worlds of nightclub and vaudeville performers overlapped.)

He also broke with vaudeville tradition in the way he ordered the show. Vaudeville custom called for the biggest act to be saved for near the end—to keep the audience waiting. The opening act might be a greenhorn tap dancer who was likely to be booed offstage. But Ed, as a newsman, was guided by the journalistic practice of starting with a hot lead, an arresting opening sentence to lure the reader into reading the entire article. He brought this reporter’s ethic to his stage shows, beginning each revue with a bang. Years later, when he competed in a medium in which audiences changed programs with the flip of a channel, his strategy of grabbing viewers upfront proved crucial to his success.

Sullivan’s players were a constantly revolving cast, though he had a few favorites. On any given night his show might include vocalist Josephine Huston, who appeared in Gershwin’s 1933 musical Pardon My English; the Three Berry Brothers, a troupe that sang and danced “in the true Harlem manner,” as one reviewer wrote; Gali-Gali, a Turkish magician who told jokes; Gloria Gilbert, a soft-shoe artist who starred in Broadway revues throughout the 1930s; and Frances Faye, a hard-driving jazz singer who originated a syncopated vocal style known as the Zaz-Zu-Zaz. Providing musical accompaniment was usually the house band, Ruby Zwerling and his Loew’s State Senators. A favorite performer of Ed’s was Yiddish dialect comic Patsy Flick, an old-time vaudevillian with whom he occasionally did a comedy sketch. Sullivan himself, in addition to hosting, narrated clips of silent movies, providing stories and humorous quips about the on-screen action.

One typical 1935 Dawn Patrol opened with Rita Rio, a jazz singer who would become a well-known big band vocalist; she sang that evening “in the accepted hot-cha fashion,” noted a reviewer. Lending a more traditional feel, Babs Ryan and Her Brothers sang vocal harmonies, and song stylists Gross and Dunn crooned updated versions of vaudeville duo Van and Schenk’s hits. Providing laughs was Dave Vine, a Jewish dialect comic, and Peg Leg Bates, “a one-legged Negro tap and acrobatic dancer, proved a sensation at yesterday’s matinee with his amazingly facile routines,” wrote a reviewer. (Bates would appear on Sullivan’s television show three times.)

Sullivan’s stage shows were uniformly well reviewed; in a small mountain of vaudeville notices there wasn’t a single sour note. Typical of the reviews was the New York Journal-American’s description of the show as “swift, funny … once again he has assembled an ingratiating lot of performers who trot out their talents in an admirable fashion.” Audiences agreed. Theater owners knew that Sullivan could be counted on to sell tickets, and between 1934 and 1937 his revues grew progressively more successful at the box office. (The city’s tepid emergence from the Depression surely helped this.)

In 1936, fellow Broadway columnist Louis Sobol reported, “Some weeks ago, columnist Ed Sullivan established a new record at Loew’s State when something like $41,000 rolled into the box office.” (Sobol, however, tweaked Sullivan by pointing out that his record was broken the following week by a George Burns—Gracie Allen show at Loew’s.) The following year, the Journal-American noted, “Ed Sullivan’s Dawn Patrol revue, at Loew’s State Theatre has broken all attendance records and will be retained for a consecutive week’s engagement.… This marks the second time in the vaudeville history of the State that a show had been held for a consecutive week’s engagement.”

As for Ed as emcee, reports were mixed. Most positively, one Dawn Patrol reviewer wrote, “In his third appearance here, Mr. Sullivan is much more at ease than he was in his debut, doing a commendable job as master of ceremonies.” Modest praise, to be sure, and contradicted by other sources. Based on eyewitness accounts of his vaudeville shows, Sullivan’s persona was much like it was in his television show, that is, stiff. As canny and skillful as he was as a producer, he was never a natural onstage. A Variety reviewer noted this after an early Sullivan vaudeville production, when Ed still shared emcee duties with Harry Rose: “Harry Rose with his aggressive style of emceeing is working hard this week and looks responsible for keeping the show together.… His sustained clicking makes it easier for the rest of the troupe, especially for Sullivan, who found Rose’s help quite handy in the microphone moments.…”

It was a central irony of his life: despite his countless hours onstage, as much as he hungered to be in front of an audience, he was never comfortable in its eye. Part of it was simple stage fright. As numerous staffers from his television show recalled, he suffered from stage nerves. This avid socializer, one of Broadway’s leading glad-handers, lost his natural charm when facing a full theater.

Adding still more gravity to Sullivan’s stage presence may have been his feelings about what he called “phonies”—those people, as he wrote in his column, who put on a false front, who pretended. He despised the fakers. Although he himself could be disingenuous, the act of adopting a suave show business persona was not in his nature. Perhaps he was too rigid, or perhaps putting on a happy face was simply distasteful to him. Either way, Ed, unequivocally, had to be Ed.

Another person, realizing he was essentially uneasy onstage, might have found an alternative. Sullivan could have been the show’s producer without acting as emcee, as in his first few shows at Loew’s State. He had the option of continuing to hire Harry Rose or another performer as master of ceremonies. Certainly the kings of vaudeville, Benjamin Keith and Edward Albee, weren’t known as onstage personalities. But something powerful drew Ed to a live audience, regardless of what small agonies this required of him. He needed to be in the spotlight. So when the Brooklyn RKO Albee, the Capitol, or Loew’s State ran ads, it was always: “In Person—Ed Sullivan—and his All New Dawn Patrol Revue.”

In 1936 Sullivan began emceeing the Harvest Moon Ball, the annual whirling-blur finale to the city’s amateur dance competition. Sponsored by the Daily News, and promoted by the paper heavily, Harvest Moon had an almost religious following. When the first unofficial contest was held in Central Park Mall in 1927, 75,000 people showed up to watch or compete, forcing city officials to cancel later contests for fear of public safety. The News relaunched the annual event at Madison Square Garden in 1935, and it grew bigger every year through the 1930s and 1940s. The Harvest Moon Ball became the country’s top amateur dance contest.

Thousands of energetic dancers competed in preliminary contests at nightclubs like the Savoy and Roseland to earn a spot in the finals, where top swing orchestras vamped as couples swirled and swung their best Lindy hop, collegiate shag, fox-trot, tango, or rhumba. The News promoted the contest as a chance at fame. “Booking agents will grab up any dance teams whose routines have the stuff upon which stardom is built,” tempted the paper. In the second year that Sullivan emceed Harvest Moon, two hundred thousand people bought tickets in the first fourteen days of the competition.

While Ed didn’t produce these yearly events, hosting them greatly boosted his profile. He parlayed their popularity to his advantage by booking the winners in his vaudeville shows. And because Harvest Moon was a dazzling visual spectacle, it was filmed for newsreels, a fact that later would profoundly influence his career.

Between writing five columns a week and producing a steady stream of vaudeville shows, Ed ran a continuous circuit between several nightclubs, that week’s vaudeville house, the Daily News office, and whatever charity event he was hosting. Meeting the incessant demands of a daily column meant trawling nightspots until near dawn and sifting through piles of tips from press agents and publicity flacks. The lineup for upcoming stage shows had to be selected and booked, and the shows themselves often played all day long. He worked the phone constantly. The pace of it all meant he sometimes banged out his column while backstage at his variety revue. One evening, theater promoter A.C. Blumenthal brought author H.G. Wells, famous for War of the Worlds, to Loew’s State to introduce him to Sullivan. Ed, typing away backstage, was so distracted that when he heard the name, he hardly looked up from his typewriter. Instead, he absented-mindedly said, “Oh, just like the English writer,” at which point Blumenthal had to tell Ed it was the English writer.

To help with his errands, Ed hired Carmine Santullo, a Bronx-born shoe-shine boy, a shy, skinny teenager with big dark eyes. He became Ed’s tireless factotum. Carmine worshipped Ed, always calling him Mr. Sullivan, and he was happy to do virtually anything for his employer: deliver Ed’s column to the Daily News office, filter and respond to mail, and help with the unending stream of phone calls. He could shrug off Ed’s sudden bursts of temper with hardly a care and anticipate his boss’s answer to any question. Carmine would remain with Ed throughout his life, becoming more of a family member than an employee. In the late 1960s, Carmine arranged for a passel of state governors to declare that February 9 would be Ed Sullivan Day.

![]()

Hollywood. By the mid 1930s the word had a whisper all its own, a come-hither suggestion of glamour and money and sex and, most of all, boundless fame. In the 1920s, Broadway and Hollywood had been close rivals in the public imagination. Broadway’s glorious Ziegfeld Follies and many touring stage shows were held in a regard similar to that of the silent pictures of Valentino. But by the 1930s the fame machine was shifting inexorably westward. Since Jolson’s first talkie in 1927, show business had never been the same.

The Broadway columnists took notice, including ever more Hollywood tidbits in their coverage. The columnists’ affection for Hollywood was far from unrequited. The studios understood the value of romancing New York’s entertainment columnists. Some columnists were even hired to appear or star in movies. If the picture made a profit—more likely with the columnist’s clout—it was an added benefit. But at the very least the studios considered the money well spent on the care and feeding of publicity sources.

Walter Winchell authored the story for 1933’s Broadway Thru a Keyhole, and it had propelled his already considerable profile still higher. And the film’s studio, 20th Century Pictures (later 20th Century Fox) was requesting more from Winchell. Sidney Skolsky, Ed’s gossip colleague at the Daily News, wrote the screenplay to the 1935 Hollywood production Daring Young Man.

Paramount in 1935 invited Ed to make a cameo appearance in Paramount Headliner: Broadway Highlights No. 2. The first Broadway Highlights film, made earlier in the year, had featured appearances by stars like Jack Benny, Al Jolson, and Sophie Tucker, emceed by Paramount studio head Adolph Zukor. Like its predecessor, Highlights No. 2 was a showcase for brief celebrity appearances, spotlighting personalities like comedian Milton Berle, crooner Rudy Vallee, screen star Norma Talmadge (whom Ed called “my favorite actress”), and boxer Benny Leonard. The short film was shown before full-length features as a studio promotion, and so was given wide release. But Ed’s minor role in this star vehicle was dwarfed by the success enjoyed by Winchell and Skolsky—and he was aware of that.

In April 1936, Fox Movietone News hired Ed to narrate a biweekly newsreel, to be shown in nine thousand theaters across the country. This was the same series of newsreels narrated by famed newsman Lowell Thomas in his march-tempo gravitas cadence. The acclaim that Ed had wanted, the national exposure, now seemed so close—but still wasn’t there. Ed’s Paramount cameo and his newsreel narration only increased his appetite for more.

By the mid 1930s, Ed began to turn his eyes westward, drawn by the allure of Hollywood. Growing up, he had dreamed of New York, and he had succeeded there, as a Broadway columnist and stage show producer. But now a far more compelling siren song called, trilling from a place that offered Stardust far surpassing that found in New York. He was well known in the city, arguably famous as a local celebrity, but he hungered for something bigger. He hobnobbed day and night with the truly famous, luminaries who were admired from coast to coast, and that’s what he wanted for himself.

He devised a plan. He had already accomplished one unlikely metamorphosis, from sports reporter to Broadway potentate. Now, in 1937, he dreamed of a far grander change: moving to Hollywood, which would catapult his star to where he had always wanted it to be. He could be a Hollywood columnist, attaching his fortunes to the ever-growing notoriety of the film capital. But the most compelling possibility was doing what Winchell and Skolsky had done. If those two typewriter-bangers could make it onto the silver screen, then surely Ed could also. He hadn’t had any success with his own attempt at film, 1933’s Mr. Broadway, but if he were a Hollywood columnist, romanced by the studios as the Coast columnists were, he could parley his status into a film career. He could be a screenwriter, maybe try his hand at acting—with the nascent film industry growing so quickly, there was no telling where it might lead.

Many had a similar plan. With the pace at which the film industry churned out pictures, its appetite for scripts was insatiable. In the summer of 1937, F. Scott Fitzgerald moved to Hollywood, enticed by visions of scriptwriting riches. At around this time or in the next few years a small crowd made a similar pilgrimage, including Robert Benchley, Dorothy Parker, Aldous Huxley, and Nathaniel West. They were undeterred by studio head Jack Warner’s description of screenwriters as “schmucks with Underwoods”—or perhaps that made the task seem all the easier.

One person stood in Ed’s way. Sidney Skolsky already covered the Daily News’ Hollywood beat and showed no signs of wanting to give it up. The paper had sent Skolsky to the Coast in 1933 to write a gossip column from inside the film colony. He had stretched his one-year assignment into four; Skolsky enjoyed the beat, with its lavish perks and access to what he thought of as the real action. Although Skolsky’s Hollywood column was printed side by side with Ed’s Broadway column—or maybe because of it—Skolsky sang the praises of the Coast over the Stem constantly. The very week that Ed’s Broadway column debuted in July 1932, Skolsky archly noted, “Notice how all the Broadway columns these days are dotted with Hollywood items. That’s because there’s nothing doing on Main Street.”

By 1936, Ed was writing of the “decline and fall of the legitimate Broadway theater” in the face of Hollywood’s advance. The problem, he explained, lay in the twelve cans of film delivered to New York’s Ziegfeld Theater. Where once the great Ziegfeld had produced his Show Boat gala live, now it was delivered to this same theater in twelve cans of film. “This is the new show business … twelve cans of film … Three hundred copies are made in the Coast laboratories … Each copy will play perhaps thirty theatres.…” Live theater, Ed reported, was “romantic, stimulating, exciting … but the new way is more profitable.” (And it was no secret that the Depression had dimmed Broadway’s lights considerably, and that the public’s hunger for Hollywood fantasy was only increased by the downturn.) Ed’s column in 1936 became a kind of de facto Hollywood-Broadway column, as he liberally sprinkled tidbits about film personalities into his Broadway coverage.

Skolsky, in what must have been agonizingly attractive to Ed, kept dropping bon bons about the joys of the Hollywood columnist. “When Gary Cooper and Madeline Carroll were announced for the cast of the flicker The General Died at Dawn, Paramount didn’t know that John O’Hara, Clifford Odets, and Sidney Skolsky would also be in the cast,” he wrote in 1936. His reporting suggested that with enough proximity, even a newshound was invited into the hallowed set, as when he went to the movies with child film star Shirley Temple. “When I arrived at the theatre Shirley was already there, seated. She didn’t say, ‘You’re late, you kept me waiting.’ She merely said, ‘Good evening, Sidney,’ and shook hands with me.”

Ed began to lobby Daily News editor Frank Hause to replace Skolsky. Exactly when he began his extended effort is unknown, but by 1937 the News management relented. They agreed to recall Skolsky to write the Broadway column and send Sullivan to Hollywood. But there was a problem: Skolsky didn’t like the idea and refused to come back to New York. “I pleaded with him by wire and phone to return but no dice,” Hause later wrote. “I guess the competition on the Broadway beat was too much for the Little Mouse, and he liked the easier tempo and climate of Hollywood.”

The News kept pushing Skolsky to return. And he kept pushing back. Finally, he chose to resign rather than return to New York. He aired his feelings publicly in Variety. “Broadway columns are as passé as Broadway,” he wrote. His column’s tagline had been “Don’t get me wrong—I love Hollywood,” but in Variety he altered it: “They got me wrong—I love Hollywood.” He took a job as the Hollywood columnist for the Daily Mirror. With Skolsky out of the way, the News assigned Ed to the Hollywood beat for one year, as they had Skolsky.

As Sullivan sat down to write his farewell Broadway column in September, he certainly had reason to feel fondly toward his New York position. The perks had been numerous. That summer the columnist had sailed to Europe aboard the SS Normandie with a group of show business stars that included Jack Benny and his wife (and comedy partner) Mary Livingston. Cole Porter was onboard to serenade the guests; one night he played the Gershwin tune “Lady Be Good” as a tribute to the composer, who had died a week earlier. Ed had plenty of free time in between filling columns with breathless tidbits like “the Cole Porters are Marlene Dietrich’s favorite shipboard companions.” While crossing the Atlantic he watched movies (appropriately, the 1937 Preston Sturges comedy Easy Living was shown). He also practiced his dance steps in preparation for hosting that fall’s Harvest Moon dance competition, and polished his Ping-Pong skills. “Your athletic reporter worked out on the desk tennis tables and thought himself pretty good,” he wrote. “Then a boy of twelve came along … he gave me a terrible shellacking, and I slunk away to the library.”

Ed’s good-bye column on September 10 was a sentimental recap of his New York years, from his beginnings at the Evening Mail in 1921 through his joy at landing his Daily News position in 1932. He veritably shoveled praise onto the News—not surprising, considering the paper had just granted him the assignment he so coveted.