Impresario: The Life and Times of Ed Sullivan - James Maguire (2006)

Part II. THE BIRTH OF TELEVISION

Chapter 15. Beatlemania

AS ED WALKED ONSTAGE TO BEGIN HIS BROADCAST on February 9, 1964, little about his demeanor revealed what this night was to be. Yet surely he felt it. In retrospect this evening’s show would be a cultural capstone, a black-and-white snapshot that defined the era as much as any of the decade’s moments. Its video footage would be replayed endlessly, as if it were some kind of visual mantra that contained the essence of its tumultuous period. Ed’s mien, however, was hardly different than during the hundreds of Sunday nights he had walked onstage over the last sixteen years.

As always, he was dressed in his trademark Dunhill suit, with a small white handkerchief jutting from the left breast pocket. His hair was slicked straight back in the same style he had worn it in since his reporter days in the early 1920s, a bit of dark hair dye the only concession to the years. The camera showed his steps to be stiff and measured. As he got to center stage, he managed a momentary smile that did little to brighten his almost cadaverous countenance.

But the studio audience’s expectant buzz was palpable. As the applause in CBS Studio 50 went on longer than usual, threatening to run away with itself, he waved his arm in a gesture of, okay kids, let’s quiet down. That afternoon at dress rehearsal he had warned the audience—largely teenage girls—to behave themselves. Otherwise, he had half-joked, he would “call in a barber.” Outside the theater at Broadway and 53rd Street there had been a near riot earlier that day, and an extra contingent of New York’s finest had been required to keep order.

He told his viewers he had just received a “very nice” telegram from Elvis and his manager, Colonel Tom Parker, wishing the Beatles—that evening’s headliner, making their American debut—“a tremendous success.” (Elvis, of course, wished the Beatles no such thing. The Fab Four, having just hit number one on the pop charts three weeks earlier, were pushing Elvis off the rock ’n’ roll throne. His resentment and envy of them is well documented; years later, in Elvis’ surprise visit to the Nixon White House, woozy with barbiturates, he explained to the president that it was groups like the Beatles who were leading kids toward drugs. But in 1964, sending this telegram was a good way to keep his name in front of the kids.)

The crowd, at the mention of Elvis and the Beatles in the same sentence, once again began bubbling over, and Ed again motioned to quiet them down. Veering from his usual practice, he began listing some of the season’s big moments: the singing nun Sister Sourire, the puppet Topo Gigio, the previous week’s duet of Sammy Davis, Jr., and Ella Fitzgerald. He was, as he often did, speaking in code: don’t worry, the teenagers don’t own this show, there’s always something for you older folks, and the little ones, too. For his studio audience, Sullivan’s catalog of the show’s allures was a minor agony, something to endure politely while attempting to keep the dam from bursting.

Then he said it. He announced that the Beatles would be out onstage shortly. At that point was heard a single female moan, apparently involuntary, almost sexual in its longing. The Beatles. Sullivan ignored it, mimicking himself as he set up the commercial break, after which he would bring on the English group: “If you’re a person who needs to be shown, here’s a rilly big proof from all new Aeroshave shaving cream.…”

![]()

Ed’s decision to book the Beatles came about partially by chance—or so the story goes. In truth, he helped invent a fabricated version of the event, a bit of creative storytelling that became accepted as historical fact.

According to Beatles lore, on the previous October 31, Ed and Sylvia were waiting for a flight in London Airport. While in London, they had visited Peter Prichard, an easygoing young Englishman who was Ed’s European talent scout, and who also worked for powerhouse British impresarios Lew and Leslie Grade. For Peter, who had performed in English vaudeville as a boy, landing the assignment as Sullivan’s eyes and ears in Europe was a dream job. He met Ed when the showman was auditioning talent agents at London’s Savoy Hotel; Peter was one of several agents Ed invited to come speak to him about their acts. Ed asked Peter to give his appraisal of the other agents’ acts. “I gave him my honest opinion, and I presume he liked it, because he called me in the next day, then he called Lew and said, ‘I’ve got your young man with me, he’s very good—he’s crafty.’ ” Over time, Prichard recalled, he and Ed developed something of a father-son relationship.

When Ed made one of his frequent trips to Europe, he always visited Peter in London, where they went to the theater together. If Ed heard of a European performer, he called Peter to investigate; the young agent also flew to Beirut, Russia, and Greece to see acts at Ed’s request. When Ed and Sylvia took their annual vacation in France, invariably staying at the Carleton Hotel in Cannes, Ed invited Peter and his wife to join them for a couple weeks. During their annual French vacations the two sat on the beach and talked for hours, Peter telling Ed about current European acts, Ed regaling the younger man with stories of his reporter days. Peter, who addressed Ed as “Mr. Sullivan” in his presence, held the showman in great regard and always listened raptly. Prichard remembered his friend as “a man’s man, tough, who wouldn’t handle fools easily.”

As Ed and Sylvia sat in London Airport in October 1963, an English rock ’n’ roll group was returning from a five-day tour of Sweden. The airport was mobbed by frenzied teenagers eager for a glimpse or a word—anything—from these young musicians. By some reports the crowd numbered close to fifteen hundred semicrazed fans. Their manic energy brought the airport to a near standstill—it even delayed Prime Minister Sir Alec Douglas-Home as his limousine was pulling into the airport. Ed knew a phenomenon when he saw one. Soon thereafter he called Peter Prichard; did Peter know who they were? Yes, they were called the Beatles, and they were becoming quite the sensation. Trusting his young friend’s opinion, Ed told him to keep track of the band. When they were ready for America he wanted to book them.

The London Airport story makes for a flattering portrait of Ed: in a moment of serendipity, the veteran showman, always looking for the next trend, spots a rock ’n’ roll band perched on the cusp of international fame. But it’s highly unlikely that Ed was in London Airport on October 31. His twice-weekly Daily News column shows him to be in New York on this date. It’s possible he could have made a trip to London between columns, but he invariably mentioned his foreign jaunts in the Daily News, and this period’s columns included no such reference. And nothing in his show’s schedule called for a trip to London in October. He was in London for a few weeks in September, at the end of his summer vacation, but there was no Beatles airport ruckus then.

By his own account, Ed first learned of the Beatles by reading the newspapers, not in an airport sighting. Ten months after the Beatles debut on his show, he wrote a letter to British showman Leslie Grade: “You have been misinformed—or understandably have forgotten how I came to sign the Beatles. In late September 1963 when we were taping acts in London, I locked up the Beatles, sight unseen, because London papers gave tremendous Page 1 coverage to the fact that both the Queen’s flight and the newly elected Prime Minister Douglas-Home’s plane to Scotland had been delayed in takeoffs for three hours. The reason: the airport runways had been completely engulfed by thousands of youngsters assembled at the airport to cheer the unknown Beatles!”

The letter contains a misstatement. The only time both the prime minister and the Beatles were at London Airport was October 31, so Ed was incorrect in his reference to late September. But his statement that he read news accounts of the band before seeing them appears true. He said as much in a 1968 interview with the Saturday Evening Post. The interviewer, noting that Sullivan told him that he learned of the Beatles in the newspapers, quoted Ed’s recollection of seeing the headlines: “ ‘Sylvia,’ he said (Mrs. Sullivan recalls it well), ‘Sylvia, there must be something here.’ ”

One other thing the letter doesn’t make clear: the news accounts of the Beatles that Ed read were probably the British clippings that Peter Prichard sent him in the fall of 1963. Throughout most of that fall, American newspapers hardly knew the Beatles existed—the band was all but unknown in the United States. And in fact it was a call from the London-based Prichard, along with these clippings, that convinced Ed to give this band a guest shot.

It’s not surprising that Sullivan booked the Beatles based on news accounts and a tip from Prichard, given how much he relied on newspapers and his talent scouts. He deserves no less credit for understanding the band’s potential. He was agreeing to present a group that, at the time he booked them, had never charted a single U.S. hit—there was an element of risk involved. Moreover, he had long been an adventurous rock promoter. Ever since Elvis he had used his hallowed talent showcase to introduce the latest rock acts to American living rooms, at a time when most adults viewed rock ’n’ roll as akin to a social disease. So the story of the London Airport sighting, with its portrait of Ed as a firsthand observer, does capture the spirit with which he stayed current with the new youth sound, if not the actual fact.

Still, Ed enjoyed the London Airport anecdote. It was almost true. He had booked the Beatles before any American promoter, he had been in London Airport just a few weeks before the band was, and the airport scene had really happened. It’s just that Sullivan wasn’t there—though at times he claimed he was. (Actually, his version varied based on his mood and what reporter he was talking to.) Just four months after the Beatles debut, he told an interviewer, “We were in London last September. There was a commotion at the airport. We inquired what the cause was and discovered that hundreds of teenagers were at the airport to see the Beatles off.” As he repeatedly put himself in London at the time of the first Beatles airport mob scene—complete with the mistaken September date—it became accepted as fact.

Peter Prichard, interviewed decades after the purported London Airport sighting, chuckled, and noted, “Well, as I always said, it’s a great press story. What can I say?” The anecdote, he said, sounds like the invention of a public relations expert. “In real life, if it would have happened, he [Sullivan] would have had a photograph of himself there.”

However, he hastened to add, “I wouldn’t argue with my boss [Sullivan]. After all these many years I wouldn’t want to end up being wrong with him. If that’s what he said he did, then hey.…” In fact, “I would never say aloud that Mr. Sullivan was wrong,” remarked Prichard. “I’ll be seeing him soon—and watch out! Imagine going through the pearly gates and seeing him coming at me.” Prichard laughed, and then imitated the famed Sullivan temper: “ ‘I’ve got to have a word with you!’ ”

![]()

Regardless of the veracity of the airport story, this much is true: in early November 1963 the Beatles’ manager, Brian Epstein, was in America on a twofold mission. He wanted to promote Billy J. Kramer, a young rock singer, and he wanted to replicate the Beatles’ European success in the United States. He had major doubts about this latter task. Epstein knew that English bands had never done well in America—and that included the Beatles. The group had released three singles in the United States, with scant success. “She Loves You” had even been played on Dick Clark’s popular American Bandstandtelevision show in September 1963, yet the tune had cast not even a shadow on the U.S. charts.

Perhaps now was the time. On October 13, the Beatles had performed on Val Parnell’s Sunday Night at the London Palladium, an English variety program that resembled the Sullivan show. With an audience of more than fifteen million, the band’s performance sparked a firestorm of fan interest that London’s Daily Mirror dubbed “Beatlemania.” It was this teenage mania that Epstein hoped to spread to the United States.

Peter Prichard, hearing that the Beatles manager sought an American television audience, placed a quick call to Epstein: “Brian was a friend of mine, and I said, ‘Don’t do anything until you’ve met up with Mr. Sullivan.’ ” Prichard then sent Sullivan a raft of positive reviews of the Beatles’ appearance on Val Parnell; he also called Ed and said the group was ripe for their American television debut. (These reviews, in fact, were likely the first news reports that Ed read about the Beatles.) As Prichard recalled, “Ed asked, ‘What’s the angle?’ ” meaning, how shall we sell this act to the public? “The angle is that these are the first long-haired boys to play before the Queen,” the agent replied. When Ed expressed interest, “I phoned Brian and said, ‘You’ll be getting a call from Mr. Sullivan.’ ”

Sullivan met with Epstein at the Delmonico on November 11. They haggled over whether the Beatles would get top billing; Epstein insisted on it, Sullivan refused—the band was virtually unknown in the United States. However, they managed to strike a deal. The Beatles would appear on February 9, and, betting on a ratings bump from the first show, Ed also booked them for the following Sunday’s show, to be broadcast from Miami’s Deauville Hotel. Additionally, he secured the rights to tape a third performance to be aired at his discretion. The fee was set at $3,500 for each live appearance, plus airfare and hotel, with an additional $3,000 for the taped segment. (The show’s budget ledger indicates that each Beatle was paid $875 for the February 9 show, which came to $515 after taxes.) That was about middling for Sullivan guests at the time; the headliners made $10,000 or more, while many acts made in the $2,500 range.

For Bob Precht, who showed up at the meeting only after negotiations were done, the booking was a source of consternation. He had no problem with the Beatles’ manager; “Brian was a bright guy—he knew what he wanted,” Precht recalled. However, Ed hadn’t consulted him, as per their arrangement. And, although Bob knew who the Beatles were, he wasn’t sure they warranted a guest shot on The Ed Sullivan Show.

Ed himself wasn’t too sure. In the second week of December, the CBS Evening News ran a report about the Beatles, a short feature produced by one of the network’s London correspondents. Shortly after the broadcast, Ed called CBS anchorman Walter Cronkite, who he was friends with. “He was excited about the story we had just run on the long-haired British group,” Cronkite said. But Ed didn’t remember the band’s name. “He said, ‘Tell me more about those, what do they call them? Those bugs or whatever they call themselves.’ ” The newsman himself couldn’t remember the group’s name, having to glance at his copy sheet to remind himself. Cronkite told Sullivan he knew nothing about the band, but said he would contact the London correspondent to give Ed more details.

Brian Epstein, having secured the Beatles’ Sullivan debut, launched his promotional assault in earnest. He had convinced Capitol Records to mount a $50,000 ad campaign, including five million “The Beatles Are Coming” stickers—all of which were reportedly affixed to surfaces across the country—and a mountain of “Be a Beatles Booster” buttons, sent to record stores and radio stations nationwide.

On December 17, a disc jockey in Washington D.C. played an advance copy of “I Want to Hold Your Hand” he had gotten from a stewardess friend; it had begun climbing English pop charts in early December. The effect was like fire in dry grass. Radio stations across the country began airing advance copies in heavy rotation. In an attempt to stay ahead of the escalating demand, Capitol Records moved up the U.S. release date from January 13 to December 26. The single began flying off record store shelves the moment it arrived.

As the mania mounted, Jack Paar attempted to steal the thunder from his rival Sullivan. The New York Times reported on December 15 that Sullivan would present the English foursome—“Elvis Presley multiplied by four”—in February. Parr saw his opening. On his January 3 TV broadcast he presented a lengthy clip of the Beatles performing “She Loves You.” Paar made light of the hysteria the group engendered, referring to the screaming girls: “I understand science is working on a cure for this.” Ed was enraged. In his eyes he had paid for an exclusive debut and the contract had been violated. He immediately called Peter Prichard in London, as the agent recalled: “Ed, as always, had a quick reaction, and said, ‘Tell them if that’s how they’re going to behave, let’s cancel them.’ ” Prichard, however, knew his friend and mentor too well to take immediate action. Instead, he merely waited for what he knew was coming. The very next day, Ed called and said that canceling the Beatles had been “a bit hasty.” Prichard assured Ed the issue had been handled.

Sullivan saw that the Paar clip had only fueled interest in the Beatles. Almost immediately, media coverage began building toward blanket saturation. Seemingly every newspaper and magazine, from The Washington Post to Life(which ran a six-page spread), began covering the band’s imminent U.S. debut. Countless publications, so recently filled with grim news of the Kennedy assassination, now had something cheery to focus on. And, of course, every Beatles article pointed to The Ed Sullivan Show.

By January 17, “I Want to Hold Your Hand” hit number one on the Cash Box charts, and by February 1st it sat atop the Billboard Hot 100. As the Beatles’ arrival inched closer—and the excitement spiraled ever higher—radio stations started counting down the days and hours to “B-Day.” By the time the band landed at New York’s newly renamed Kennedy International Airport on early Friday afternoon, February 7, hysteria ruled. Some three thousand teenagers (chaperoned by one hundred ten police) clamored to greet them. Describing the crowd, one reporter wrote, “There were girls, girls, and more girls.” A battalion of two hundred reporters and photographers were on hand, peppering the foursome with queries:

“Will you sing for us?”

“We need some money first,” John said.

“Do you hope to get haircuts?”

“We had one yesterday,” George explained.

“Are you a part of a social rebellion against the older generation?”

“It’s a dirty lie,” replied John.

The band’s limousines (one for each Beatle) ferried them to the Plaza, one of the city’s most recherché hotels, which had to endure days of mania. Girls hired taxicabs to deliver them to the front door, explaining to wary doormen that they had rooms there. The hovering crowd sang Beatles songs, or a tune from Bye Bye Birdie with changed lyrics: “We love you Beatles, oh yes we do!”

Ed, overjoyed at all the attention, allowed myriad reporters into Saturday’s rehearsal, which he attended, a rarity since Bob Precht normally handled it without him. For one of the band’s sets, set designer Bill Bohnert had created an elaborate backdrop spelling out the name Beatles. But Ed, examining it while surrounded by reporters, proclaimed: “Everybody already knows who the Beatles are, so we won’t use this set.” Because it was the only backdrop Ed had ever vetoed, Bohnert was convinced it was Sullivan’s way of reminding everyone who was in charge.

Vince Calandra, a production assistant, worked with the Beatles as they set up onstage. George Harrison had stayed back at the hotel suffering a high fever, and Calandra took his place during camera setup, wearing a Beatles wig for authenticity. Vince began chatting with the musicians, and Paul McCartney told him that he and John Lennon had often dreamed of playing the Sullivan show, long before the actual booking. “McCartney said that he and John were talking on the plane over, and they felt that once they had done The Ed Sullivan Show, that was going to be their claim to having made it,” Calandra recalled. As they stood talking, John Lennon asked Vince: “Is this the same stage that Buddy Holly performed on?” To Lennon’s delight, Calandra confirmed that it was.

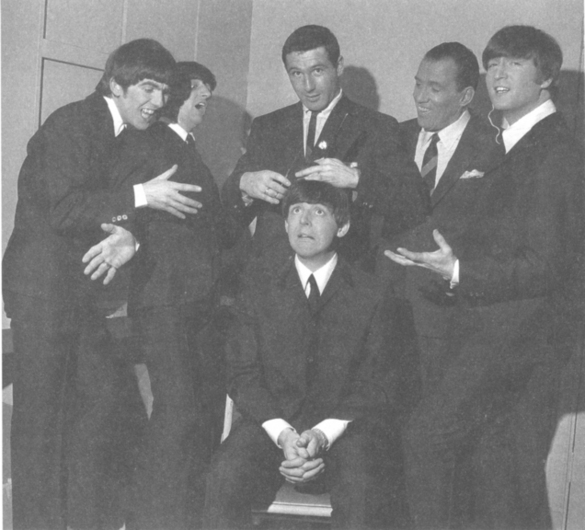

Pretending to give Paul McCartney a much-needed haircut, February 1964. Sullivan was deliriously happy with the ratings the Beatles generated. (CBS Photo Archive)

Getting a ticket to the rehearsal or broadcast was nearly impossible: the show received over fifty thousand requests, so obtaining one required a personal connection with CBS, Capitol Records, or the show’s sponsors. (The night of the performance, a number of girls were caught trying to enter through the air conditioning ducts.) Ed made sure that Jack Paar’s daughter Randy got tickets, which helped remind her father that Sullivan had scored the big scoop. On the other hand, Ed denied requests by three CBS vice presidents—his way of snubbing the management. In the moments before rehearsal the seven hundred twenty-eight-seat theater quivered with anticipation. When a crewmember wheeled Ringo’s drums onstage, the audience experienced its first moment of near hysteria. Ed gave them a stern lecture on the importance of paying attention to all the show’s performers, and he exacted a promise of good behavior from the teenagers.

With the Fab Four, February 1964. Their debut performance on the Sullivan show signaled a new era in American popular culture. (Getty Images)

As Ed sat offstage with his unlined pad of paper, preparing his introductory remarks, Brian Epstein approached him. The Beatles’ manager, a master of creating the image of his “boys”—for years they wore matching outfits at his directive—asked to see Sullivan’s remarks about the band. The request was almost comical: a twenty-nine-year-old rock ’n’ roll manager thinking he was going to check Ed’s introductions. “I would like for you to get lost,” Sullivan said, without looking up.

![]()

Almost double The Ed Sullivan Show’s usual audience was watching that night as the black-and-white CBS broadcast returned from its first commercial break. Like most of the stage shows Ed had produced since the 1930s, this evening’s program followed the columnist’s rule: to lead with the top item. So the Beatles’ moment had come.

Ed, now apparently feeling the awesome weight of anticipation, shifted back and forth from foot to foot, projecting even more discomfort than in his usual stage unease. As he launched into his introduction, he bobbed forward stiffly, as if he was an old pugilist preparing to throw a late-round knockout punch.

The showman ran pell-mell through his cue card, dropping almost as many syllables as he pronounced:

“Now yesterday and today our theater’s been jammed with newspapermen and hundreds of photographers from all over the nation and these veterans agree with me that the city has never witnessed the excitement stirred by these youngsters from Liverpool who call themselves the Beatles”—at this point he refused to pause even for a moment, knowing that if he did the barely constrained volcano might erupt before he finished—“Now tonight, you’re going to twice be entertained by them—right now, and again in the second half of our show. Ladies and gentlemen…the Beatles! Let’s bring ’em out!”

Ed let his voice get carried away with the excitement, swooping his right arm in a roundhouse gesture toward stage left—who says this man is wooden?—and the studio audience experienced spontaneous combustion, giving voice to a full-throated primordial shriek expressing some otherworldly frenzy, equal parts romantic longing, lust, and sheer amazement that such creatures as inhabited the stage actually existed.

The camera panned over this female teenage riot, bouffants and pageboys shaking, arms akimbo and mouths agape, then settled on the Beatles, who, after Paul’s brisk count off, snapped into the mid-tempo “All My Loving.” Dressed in matching Edwardian suits with white shirts and ties, equipped with carefully coiffed mop tops, they appeared closer to terminally cute than revolutionary. The set had a mod look, with oversized white arrows pointing toward a center performance area, bathed in light from above. In the middle of this cleanly geometric stage, bobbing their heads in time to the music, it appeared possible the foursome might be aliens from another planet designed to drive earthlings batty. Paul smiled and sang lead, shaking his bangs with boyish charm, George and John crooned harmonies, and Ringo managed to look cool and goofy at the same time. The music was all but drowned in audience screams through much of the song, but it didn’t matter; the foursome’s buoyant energy proved able to break through every barrier, social or musical, put before it.

After their first number, they paused only briefly for a bow before beginning the sweet “Till There Was You.” In mid song the camera lingered over each member in turn, superimposing his name (during John’s section it read “Sorry girls: he’s married”). From this ballad the group jumped into “She Loves You” (“she loves you, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah!”). This, finally, was really rock ’n’ roll—fast insistent energy, the beat a rapid foot tapper, and they played it like joyful demons, three minutes of exuberant youthfulness, all about love and sex and having a good time. John smiled along with Paul as they belted out the melody. Being young had never seemed so attractive, so unbound by what came before. In the time it took to play three pop songs, America made a tectonic shift toward being a youth-oriented culture. As “She Loves You” ended, the studio audience kept shrieking like the theater was on fire—which, in a sense, it was.

![]()

Ed was to bring back the Fab Four for two more numbers, but first the studio audience had to behave itself through the other acts—such a difficult task that Sullivan interrupted his next introduction to demand quiet, papering over his pique with a small smile as he reminded the audience of its pledge of good conduct.

Following the Beatles was tuxedo-clad magician Fred Kaps, who did card tricks and—like magic—poured salt endlessly out of a small salt shaker; the cast from the Broadway musical Oliver! (including Davy Jones, who later fronted the pop group the Monkees) reprised two numbers; impressionist Frank Gorshin portrayed the White House staff as if it were peopled with actors (Gorshin went on to play the Riddler in the Batman TV series); Tessie O’Shea, an ample-girthed grand dame of English cabaret, wielded a copious fur boa while razzmatazzing show tunes—“This is gonna be sexy!” she warned; the comedy duo McCall and Brill rambled through a routine about casting calls. Then, after a commercial for Kent cigarettes, Ed, visibly relaxed, reintroduced the Beatles with a huge swiveling arm gesture: “Ladies and gentlemen, once again!”

Proving that, remarkably, they could top even themselves, the band galloped through “I Saw Her Standing There,” Paul and John tossing off sexy yowls while smiling in unison and shaking their matching mop tops. As the Beatles kept jouncing in time to the music, the studio audience’s excitement kept escalating in cascading, vibrating waves. Watching from the control room, Bob Precht remarked: “I don’t believe this—this is unreal.” Then the Beatles destroyed the last remnants of feeble resistance with their current number one hit, “I Want to Hold Your Hand,” with Ringo driving the steady backbeat, and John, Paul, and George giving the song a big ending by bobbing their guitars in choreographed rhythm. The boys, after taking their customary bow, walked over and shook Mr. Sullivan’s hand, each flashing a big smile as he did so. Speaking would have been impossible amid the hail of screeching, so the emcee sent them offstage with a nod of his head. The British Invasion had just begun, but the American surrender was already unconditional.

![]()

As Ed opened the following Sunday’s show, broadcast from Miami’s Deauville Hotel, he was in obvious high spirits. His introductory remarks explained his ebullience: “Last Sunday, on our show in New York, the Beatles played to the greatest TV audience that’s ever been assembled in the history of American TV.” Ed’s boast was correct. The Sullivan show’s Nielsen ratings in the early to mid 1960s hovered in the twenty-three to twenty-five range, meaning its typical audience was close to forty million viewers a week, or somewhat less than a quarter of the country. Surpassing even this gargantuan figure, the Beatles debut was a blowout. Its Nielsen rating of 44.6 translated to 73.9 million viewers—the largest audience in television history at the time.

“Now tonight, here in Miamah Beach”—he never pronounced the city’s name correctly despite traveling there annually for decades—“again the Beatles face a record-busting audience.” His statement wasn’t quite correct; this evening’s Nielsens would indicate an audience of seventy million, just a tad down from the prior Sunday’s. Still, the skyrocketing ratings were making Ed almost giddy. As the crowd began murmuring at his mention of the Beatles, he held up his hands and bellowed “Wait!” but his high-beam grin appeared so happy the audience responded with a big chuckle. “Ladies and gentlemen, here are four of the nicest young people we’ve ever had on our stage—the Beatles, bring ’em on!”

While Ed was speaking, the band had been struggling to get onstage. Shortly before showtime, they took the elevator down from their hotel rooms, only to see an impenetrable crowd of fans blocking the stage entrance. They tried to get through politely, without making any headway, finally breaking through with the assistance of a phalanx of Miami police. As Sullivan staffer Bill Bohnert remembered, Ed finished his introduction, “Just as Ringo was sitting down and picking up his sticks.”

Clad in matching light-colored Edwardian suits, the band vaulted into a foot-tapping “She Loves You.” If the week before the group had been charged with energy, now their performance felt freer; apparently having passed the audition allowed them to enjoy playing to its fullest. Paul almost danced along with the backbeat as John happily bobbed in time. After only a moment’s pause they slid into the romantic “This Boy.” Although the band was at its freest, the Miami audience was more subdued than the previous week’s. A camera pan of the audience revealed why: much of the twenty-six-hundred-member crowd was middle-aged. As the Miami Herald reported, “The oldsters outdid the kids in mobbing The Ed Sullivan Show. A man in a white dinner jacket threw a wicked right at a young usher. A grandmother hammered a head with her high heels in her hand.” To end their set, Paul said hello in his charming cockney accent and promoted the band’s new album, then sang lead vocal on the up-tempo “All My Loving,” with sweet harmonies by John and George.

Outside the theater, some Sullivan crewmembers found themselves in danger. Hundreds of teenagers, unable to get inside, spotted the broadcast control truck parked in back of the theater. As Bill Bohnert remembered, “The door of the truck was open, and I looked out just as I saw a wave of people coming … they came roaring toward the truck, and I slammed the door shut just as this wave literally hit the truck—you could feel the truck shake.” The vehicle kept rocking back and forth as the mob attempted to find some way to watch or hear the broadcast.

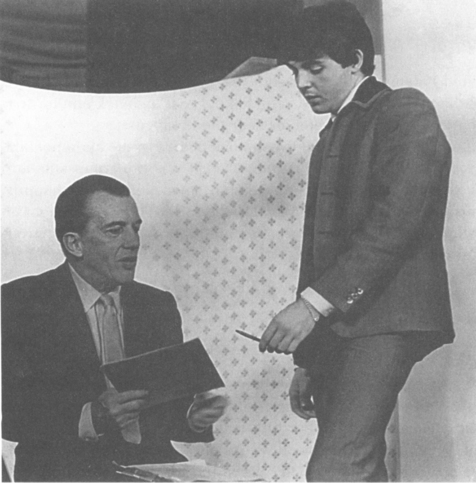

Paul McCartney getting Sullivan’s autograph. McCartney and John Lennon had long dreamed of playing the Sullivan show. (Globe Photos)

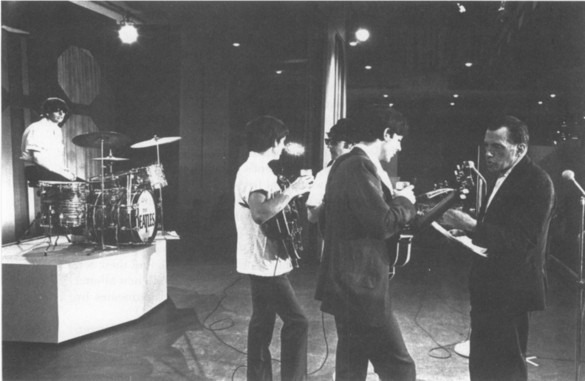

Rehearsal for the Beatles’ second Sullivan show appearance, February 16, 1964. (CBS Photo Archive)

After the Beatles’ first set, Ed introduced two famous boxers in the audience; the switch from rock ’n’ roll to boxing felt incongruous, yet it was Sullivan’s standard format. Reigning heavyweight champion Sonny Liston stood and waved happily, while 1940s-era champ Joe Louis managed only a dour smile. Then Ed brought on comedy team Marty Allen and Steve Rossi, who bantered in a vaudeville-style routine in which a reporter interviews a boxer:

Rossi: Would you say you’re the best fighter in the country?

Allen: Yeah, but in the city they murder me.

Rossi: Who taught you to fight?

Allen: Rocky Marciano, Joe Louis, Sugar Ray, and Elizabeth Taylor.

Following the comics was a singer who would have been this evening’s headliner if the Beatles had bombed the prior week, leggy Hollywood chanteuse Mitzi Gaynor. In a blond bouffant and accompanied by four tuxedoed dancers, Gaynor shimmied through “Too Darn Hot,” changing up the mood with a sultry cocktail ballad, finishing with a brassy blues medley that ended with “When the Saints Go Marching In.”

Ed came on and told the audience an impressive bit of fiction: “The greatest thrill for the Beatles—and we got a big kick out of it—is the fact that they were actually going to meet Mitzi Gaynor tonight on our show.” If his intent was to make the Beatles appear as typical starstruck youth, he succeeded with at least part of the studio audience, who sighed appreciatively. But the idea that the foursome was eager to meet the milquetoast star of light musicals was patently absurd. Still feeling chipper, Ed interrupted himself to check his microphone. “Is this off, too?” he asked, glancing up at the microphone above him. Getting no answer, he muttered “Communists!” which prompted a reflexive laugh from the audience.

The showman presented a taped segment from Miami’s Hialeah Race Track in which a four-person acrobatic troupe named the Nerveless Nocks swayed on one-hundred-foot poles while performing tricks—“One of them almost lost their life doing that,” Ed reported. The live broadcast resumed as Sullivan brought on comic Myron Cohen, whose routine was pure Borscht Belt. (“A priest, a minister, and a rabbi are playing cards …”)

When Ed reintroduced the Beatles for their final set, he attempted a joke based on their song titles. In two weeks, boxer Sonny Liston would face Cassius Clay (soon to change his name to Muhammad Ali). “Sonny Liston, some of these songs could fit you in your fight—one song is ‘From Me to You.’ And another one could fit Cassius, because that song is ‘I Want to Hold Your Hand.’ ” The attempt at humor fell like a dull thud, though the audience offered a polite chuckle. Then: “Ladies and gentlemen, here are the Beatles!”

The energized quartet launched into an exuberant “I Saw Her Standing There,” in which John had to stoop to reach his too-low mike stand, but it didn’t seem to matter—the band was in rollicking good spirits, bouncing up and down as they strummed. John and Paul howled in unison at the verse’s end to set up a guitar solo by George. They stopped just long enough for Paul to count off—“One! Two! Three!”—before jumping into a fast take of “From Me to You.” To introduce their last number, Paul made his own attempt at humor: “This is one that was recorded by our favorite American group, Sophie Tucker.” The audience didn’t get the cheeky humor; was an eighty-year-old vaudevillian really this rock ’n’ roller’s favorite band? (The joke went over well in England, where audiences understood that Paul meant that the large-sized Tucker was big enough to be called a group.) The crowd’s silent response was interrupted by a single man laughing, very loud, continuing to guffaw through the first guitar strums; it sounded like Sullivan, who doubtless found the notion amusing. Then the band delivered “I Want to Hold Your Hand” as a dose of fun-loving sunshine, galloping through verse and chorus like the tune was happiness itself.

As the audience wailed and cheered, the Beatles walked over to Ed, who told them—and here Ed was addressing older viewers at home: “Richard Rodgers, one of America’s greatest composers, wanted to congratulate you, and tell the four of you that he is one of your most rabid fans. And that goes for me, too. Let’s have a fine hand for these fellows!”

A few days later, Ed and Bob Precht hosted a dinner for the Beatles and the staff, partially as a perk for the staff; their reward for working hard was an opportunity to mingle with the band. The musicians split up to sit at different tables, so all of the fifteen or so staff members had a chance to say hello. Over the course of the evening the crew found the foursome thoroughly charming. One of the secretaries remarked that Ringo felt a touch of melancholy because, having enjoyed himself so profoundly on his first American trip, he observed, “This was the best it was ever going to be—it could never get better than this.”

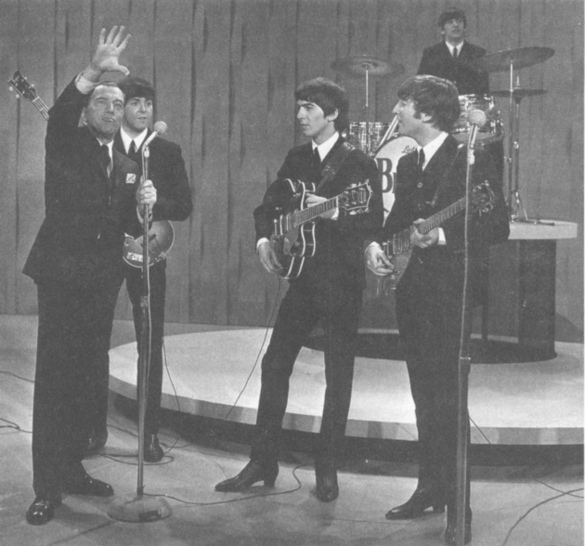

The Beatles on the Sullivan show, February 1964. Sullivan attempted to quiet the crowd, which was hardly possible. (CBS Photo Archive)

![]()

Ed had bestowed the Sullivan seal of approval on the new rock ’n’ roll sensation, and that, initially at least, appeared to be a safe bet. Within sixty days the Beatles held the top five spots on the Billboard Hot 100, with fourteen of their hits in the top one hundred chart positions, two feats that have never been topped. The band’s third Sullivan appearance on February 23 provided still another ratings jolt, though not as dramatic as the first two evenings. This third Beatles performance was taped the afternoon of their debut, and edited together with a show taped in front of a live audience to present the illusion of a live performance. Ed even recorded introductions suggesting the Beatles were live: “You know, we discussed it today, we’re all gonna miss them. They’re a nice bunch of kids.” (Additionally, in the spring of 1964, Ed flew to London to interview the Beatles on the set of A Hard Day’s Night, and presented this segment during a May broadcast.) The publicity value of the Beatles appearances was incalculable, as legions of reporters and television crews trailed the band’s every move during their first American trip, with all the reports mentioning the Sullivan show. The Beatles broadcasts and the attendant tidal wave of publicity boosted The Ed Sullivan Show’s ratings enough to make it the 1963-64 television season’s eighth-ranked show.

The meeting of these two major entities, the life force of the Beatles with the national institution that was The Ed Sullivan Show, produced some kind of cultural fission, an inestimable spark of change, a sense that the season had turned irrevocably. It was all anybody was talking about. If Ed had always dreamed of fame, in these weeks he entered a stratosphere of cultural primacy that even he had never imagined. The showman basked in his glory.

Dissenters, however, sat unhappily in living rooms across America. Their apprehension was only partially voiced by the critics, who reviewed the Beatles’ Sullivan debut as if it were slightly rotten fruit. The New York Timesreviewer, who compared the Beatles’ haircuts to that of children’s show host Captain Kangaroo, and who referred to Ed as “the chaperone of the year,” observed that, “In their sophisticated understanding that the life of a fad depends on the performance of the audience, and not on the stage, the Beatles were decidedly effective.” Joining the chorus, The Washington Post’s critic opined that the musicians were “imported hillbillies who look like sheepdogs and sound like alley cats in agony.” Critics, however, were a group that Ed had always succeeded in spite of; it was the home audience he worried about, and he understood that a deep sense of unease hid beneath the mostly bemused reviewers’ barbs.

For some, the Beatles were a novelty; for others, of course, the group was as thrilling as anything they had ever seen. For another segment, however, the fast music, the long hair, the out-of-control teens—it all made them distinctly uncomfortable. “I was offended by the long hair,” recalled Walter Cronkite, who represented the voice of mainstream America as much as anyone. “Their music did not appeal to me either.” Part of Ed’s nearly flawless sense of the public’s taste was his deep reverence for—even wariness toward—conservative values. He was, after all, helping to create the status quo. He decided which artists and entertainers performed live for his massive national audience, which performers received the hallowed Sullivan imprimatur of acceptability. This was a delicate balancing act since survival meant entertaining everyone while offending no one.

Sullivan’s cautious, stolid nature worked in his favor in this regard. He had never wanted to be a leader, never wanted to take the public where it wasn’t ready to go. To keep the show in a dominant position he had to walk in lockstep, or just a step ahead, with a fickle public. Any move toward change had to be made carefully. His most precious talent was his ability to sense audience desire and to gratify that desire. The Beatles booking demonstrated that Sullivan the producer—the global talent scout—continued to have an unerring nose for ratings gold. But was his audience the unified entity it always had been?

Elvis, seven years earlier, had prompted a major backlash, with angry letter writers decrying what they saw as the singer’s corrupting influence on youth. Yet while Presley turned the pop song into a vehicle for rambunctious sexuality, ultimately he was a nice boy with an “aw shucks” quality, who used his royalties to buy a new house for his parents. The Beatles were something else. All those teens in near riot—they actually required police to contain them—whatever this was about, it wasn’t about deep reverence for conservative values. When the New York press corps greeting the Beatles at the airport had asked, “Are you part of a social rebellion against the older generation?” it had been a serious question. And social rebellion was not part of what had allowed Sullivan to outlast the competition since 1948.

The Reverend Billy Graham, who had violated his rule against television on the Sabbath to watch the Beatles, seemed to speak for some of Sullivan’s audience. The band was a symptom of “the uncertainty of the times and the confusion about us,” he said. The problem for those viewers who felt as Graham did was that the show would soon take on a new tone. Spurred by the Beatles ratings spike, by the spring of 1964 Sullivan was booking a plethora of rock acts, changing the program in ways that many found disturbing. “Frequent appearances of rock ’n’ roll groups on The Ed Sullivan Show have turned the show into a teenage attraction that creates problems for the producers and the Columbia Broadcasting System,” reported The New York Times. The problem was the teenagers themselves. Something had changed; the teens visiting the Sullivan show “set up an hour-long din that distracts other performers and mars the audio portion of the show.” In response, the show stopped admitting anyone under age 16 unless accompanied by a parent. That was one solution, but a reporter—surely echoing what many parents hoped—suggested another: couldn’t the show just stop booking rock ’n’ roll?

“That’s a possibility,” Bob Precht said, “but we feel strongly that rock ’n’ roll is part of the entertainment scene. Such groups are selling records like mad. We can’t ignore an important trend in our business. We don’t want to be a rock ’n’ roll show, but there is value in having youngsters watch our show.” In other words, The Ed Sullivan Show was trying to have it both ways, to satisfy two audiences—teens and their parents—who now wanted very different things. The “Big Tent” was being stretched further than ever before.