Edison and the Electric Chair: A Story of Light and Death - Mark Essig (2005)

Chapter 2. The Inventor

THOMAS ALVA EDISON began his working life in i860, at the age of thirteen, when he took a job as a "news butch" selling newspapers and candy on the Grand Trunk Railway that ran between Detroit and his home in Port Huron, Michigan. The job did not pay well, but he found ways to supplement his income. On April 6,1862, the Detroit Free Press was filled with news of the Civil War battle at Shiloh. Before the train started its return trip to Port Huron, Edison acquired 1,000 instead of his usual 100 papers and bribed a telegraph operator to wire news of the battle to stations along the line. At each stop the train was greeted by crowds of men eager for details of the battle, and Edison made a small fortune selling copies of the Free Press at five times the usual price.

Even as a boy, Edison displayed the skills that would serve him well for the rest of his life: an eye for the main chance, a knack for publicity, and a grasp of the possibilities of the latest technology.1

The young Edison—Alva to his mother, Al to his friends—never received much formal education. Born in February 1847, he spent the first seven years of his life in Milan, Ohio, before his father, a shingle maker, moved the family to Port Huron, where he attended school for less than a year. "Teachers told us to keep him in the streets, for he would never make a scholar," Edison's father reported. "Some folks thought he was a little addled." Edison's mother taught him to read at home.2

The Grand Trunk left Port Huron each morning at seven and arrived about four hours later in Detroit, where it stopped over until the return journey started in the evening. To fill the long afternoons, Edison joined the Detroit Young Men's Society and pored over the science books in its library. After reading a chemistry text, he bought chemicals, crucibles, and beakers, installed a laboratory in the train's baggage car, and spent many happy hours experimenting—until a broken bottle of phosphorus set the car on fire, and the enraged baggage master dumped the boy's laboratory onto the tracks. Edison later recalled that the baggage master "boxed my ears so severely that I got somewhat deaf thereafter." (Hearing problems would plague him for the rest of his life.)3

Seeking other outlets for his curiosity, Edison practiced on the equipment at railway telegraph offices. In 1862 he plucked a small boy from the path of a rolling freight car, and the boy's father, a telegraph operator, gave Edison formal telegraph lessons as a reward. His training complete, he left home at age sixteen to become a "tramp" telegrapher, moving from city to city in search of new jobs and new experiences. Between 1863 and 1868 he lived in Ontario, Toledo, Indianapolis, Cincinnati, Memphis, Louisville, and New Orleans.4

Edison at the age of fourteen, when he worked as a "news butch" on the Grand Trunk Railway in Michigan.

Within the hard-drinking, hard-living fraternity of tramp telegraphers, Edison stood apart. Not content to listen and transcribe, he wanted to understand the principles underlying the devices he used each day. While other men avoided night shifts as an impediment to carousing, Edison embraced them because they left his days open for experimenting on equipment and reading technical journals and books (one of his favorites was Michael Faraday's Researches in Electricity). Even Edison's amusements were scientific. At one point he and a friend acquired a device called an induction coil—which transformed low voltages from an electric battery into painful shocks—and wired it to the metal sink in a railroad roundhouse. As unwitting victims touched the sink, they shouted and jumped into the air. "We enjoyed the sport immensely," Edison said.5

In 1868 Edison landed a job with Western Union in Boston and appeared for his first day of work dressed in a blue flannel shirt, jeans, a wrinkled jacket, and a hat with a torn brim. The finely dressed Boston operators, amused by his rough appearance, took to calling him "the Looney" and hatched a plan to haze him. On his first shift, he was asked to receive press copy from New York. The New York operator, who was in on the plot, began to transmit at the rapid clip of twenty-five words per minute, but Edison kept pace easily. When the speed increased to a dizzying thirty, then thirty-five words per minute, Edison still did not waver. Finally, when the New York operator began to skip and abbreviate words, Edison was forced to break. He tapped a message down the wire to New York: "You seem to be tired, suppose you send a while with your other foot." The Boston operators burst into laughter. The episode "saved me," Edison said. "After this, I was all right with the other operators."6

Despite his receiving skills, Edison was less interested in operating than in experimenting with the equipment. At the time, Boston was second only to New York as a center of telegraphy in the United States. Using contacts forged during his years as an operator, Edison found investors willing to fund his experiments on telegraph printers, fire alarm systems, and a vote recorder. The last device—for tallying votes in legislative houses—never found a market, but it was historic nonetheless: It became Edison's first patented invention, U.S. Patent 90,646, issued June 1, 1869. The lawyer who filed this patent application for Edison described the young inventor as "uncouth in manner, a chewer rather than a smoker of tobacco, but full of intelligence and ideas." With a couple of partners Edison started a business providing gold and stock quotations for banks and brokerage houses. Buoyed by initial success, he quit his job with Western Union and in January 1869 placed a notice in the journal Telegrapher announcing that he would now "devote his time to bringing out inventions."7

Within a few months of this announcement, he withdrew from the Boston enterprise and moved to New York, where he formed a partnership with Franklin Pope, a prominent expert in telegraphy, and James Ashley, an editor of Telegrapher. By the end of 1870, the three had developed a telegraph printer and sold the rights to it for $15,000 (roughly the equivalent of $250,000 today). Shortly after the sale, the partnership split apart on bitter terms. Edison claimed Ashley and Pope tried to cheat him out of money, while they accused Edison of violating the partnership agreement by striking his own deals with manufacturers.8

The rift did not slow Edison's career. After the quick success of the printer, his inventing skills were in high demand. He signed contracts to develop inventions for several telegraph firms and, with the money they provided, opened a laboratory and manufacturing operation in Newark that employed more than forty-five hands. (In a letter to his parents back in Michigan, he described himself as a "Bloated Eastern Manufacturer.") A telegraphic news service he started failed after a few months, but it proved important nonetheless: The twenty-four-year-old Edison courted one of the company's employees—Mary Stil-well, age sixteen—and married her on Christmas Day 1871. 9

The main financial backer of Edison's Newark shops was the Gold & Stock Telegraph Company, for whom he developed the Universal stock printer, a device that became the industry standard, ticking out stock prices in brokers' offices all around the world. When Western Union bought control of Gold & Stock in 1871, Edison came under the wing of the industry giant. Western Union was particularly eager to finance Edison's research into duplex telegraphy, which allowed two messages to be sent simultaneously on the same wire, one in each direction. The company expected Edison simply to refine existing duplex technology, but Edison developed something revolutionary: the quadruplex telegraph, which allowed simultaneous transmission of two signals in each direction over one wire. By doubling the capacity of its wires, the quadruplex promised to save Western Union a great deal of money by limiting its biggest cash drain, the need to build and maintain wires. After Edison perfected his quadruplex and patented it, Western Union gave him a $5,000 advance payment and opened negotiations for purchase of full rights.10

Although Western Union had funded Edison's research, he had never signed a formal contract with the company. When the company was slow in coming to terms, the inventor therefore felt free to entertain an offer from Jay Gould. A notorious financier who had nearly cornered the gold market a few years earlier, Gould now wanted to challenge Western Union for control of the long-distance telegraph industry, and Edison's quadruplex was the key to his plan. When Western Union finally tendered a firm offer to Edison in January 1875, it was shocked to learn that the rights were no longer available; two weeks earlier Edison had sold out to Gould's company, Atlantic & Pacific, for $30,000. Western Union's president remarked that Edison had "a vacuum where his conscience ought to be."11*

WITH THE MONEY from the quadruplex and his other inventions, in 1876 the twenty-eight-year-old Edison built himself a new laboratory in the sleepy hamlet of Menlo Park, New Jersey, about twenty-five miles southwest of Manhattan. A few other men operated electrical and telegraphic laboratories at the time: The inventor Moses Farmer, for instance, worked on telegraphic and other electrical equipment from a small laboratory in Boston, and Elisha Gray conducted experiments at the shops of the Western Electric Manufacturing Company. But Edison's early triumphs allowed him to operate on a different scale. In a two-story frame building in Menlo Park, he built the best laboratory in the country and hired the most talented mechanics. He called it his "invention factory," and he had such faith in himself, his men, and his new lab that he predicted "a minor invention every ten days and a big thing every six months or so."12

R. F. Outcault's illustration of Edison's laboratory complex in Menlo Park, New jersey, as it appeared in 1881. The long building in the center is the main laboratory.

The first major invention to emerge from Menlo Park was a refined version of the device Alexander Graham Bell had first unveiled in 1876: the telephone. In Bell's telephone transmitter, the sound waves of the human voice vibrated a metal diaphragm, which induced an electric 21 current in an electromagnet. The current traveled over a wire and into a receiver, which essentially was a transmitter in reverse—an electromagnet vibrated a metal diaphragm, which (at least in theory) reproduced the original sound. Early users of Bell's telephone found, however, that voices emerging from the receiver were nearly unintelligible. The problem, Edison discovered, was the transmitter's electromagnet, which did a poor job of translating sound waves into electric current. Sensing an opportunity to win a patent on a crucial component of the telephone, Edison began experimenting on transmitters. He found that by replacing the electromagnet with buttons of compressed carbon, he could faithfully reproduce the modulations of the human voice. Edison's new carbon transmitter transformed the telephone from a novelty into a practical means of communication-and soon provided him with a fresh stream of income.

The telephone work led directly to another invention. At the time, when telephones were still largely in the experimental stage, no one had imagined a day when the instrument would be in every home and office, allowing people to speak directly to each other. Edison, like most other observers, expected that the telephone would function just as the telegraph system did, with an operator transcribing a voice message and delivering it to the recipient. The electrical pulses of a telegraph message could be preserved and replayed at a later time; Edison believed a telephone system should have a similar capability. The goal, as Edison described it in July 1877, was to "store up St reproduce automatically at any future time the human voice."13

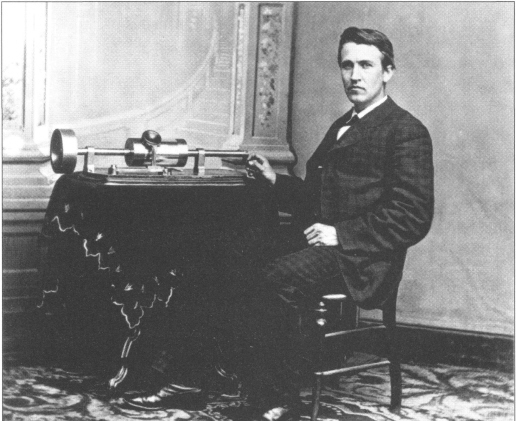

Edison earlier had invented a device to record the electrical impulses of telegraph messages on waxed paper tape, and he also knew that the human voice created vibrations in the diaphragm of a telephone transmitter. He decided to see if these vibrations, like the telegraph messages, could be embossed and repeated. Late in 1877 Edison designed a lathelike machine consisting of a cylinder wrapped with tinfoil and attached to a hand crank. There were two diaphragms, each attached to a needle. One needle would emboss the sound waves into the foil; the other, in passing over the indentations, would reproduce the original sound.

One of the Menlo Park workers built the device to Edison's specifications, and it surprised everyone by working the first time it was tried. Edison called it the phonograph, or "sound writer."

Edward H. Johnson, a business associate of Edison's since the early 1870s and a master showman, took charge of promoting the phonograph in public exhibits up and down the East Coast. The concept was so novel that many people refused to believe it. A Yale professor insisted that the "idea of a talking machine is ridiculous" and advised Edison to disavow published accounts of the phonograph in order to protect his "good reputation as an inventor." Many were convinced that Edison was simply a ventriloquist, throwing his voice into the machine. A visiting minister rapidly shouted a tongue-twisting string of biblical names into the phonograph; only when the machine spit them back precisely did he believe that Edison had no tricks up his sleeve. On an April 1878 trip to Washington, D.C., Edison entertained President Rutherford B. Hayes and his wife with the phonograph until three in the morning.14

Before he invented the phonograph, Edison was well known to Wall Street and telegraph men. Afterward, he became one of the most famous men in the world. When reporters flocked to Menlo Park to interview the creator of this marvelous machine, they were surprised to encounter not a solemn man of science but a beaming, boyish inventor. Pants baggy and unpressed, vest flying open, coat stained with grease, hands discolored by acid, Edison "looked like nothing so much as a country store keeper hurrying to fill an order of prunes." Newspapers described a man who rarely slept and who appeared to subsist entirely on pie, coffee, chewing tobacco, and cigars. Because of his partial deafness, which had grown worse since boyhood, Edison's face took on an aspect of gravely serious concentration when he listened, but when he described his latest inventions in his high-pitched voice, his gray eyes flashed and his smooth-shaven face lit up with joy. In 1878 the New York Daily Graphic coined the nickname that would follow him the rest of his life: "the Wizard of Menlo Park." Edison seemed to be a distillation of America's self-image—unpolished and unpretentious yet gripped by an ambition to transform the world.15

Edison with his newly invented phonograph. The famed Civil War photographer Mathew Brady took this portrait during Edison's 1878 trip to Washington, D.C.

. . .

EDISON CRAVED the public's attention, but it also exhausted him. By the late spring of 1878, he was tired and ill. He had been working at a frantic pace for more than a year and had not had a vacation since his honeymoon nearly seven years before. When a friend invited him to join an expedition traveling to the Wyoming Territory to view a solar eclipse, he jumped at the chance.16

Edison spurned the comforts of the expedition's reserved railroad car and instead spent much of the journey perched precariously on the cowcatcher, the wedge at the front of the locomotive designed to pitch cows and other obstacles out of the train's path. Despite its dangers—at one point, Edison later recalled, "the locomotive struck an animal about the size of a small cub bear, which I think was a badger," and he barely dodged out of the way—the spot allowed Edison to breathe the clear air of the West, untroubled by the black smoke billowing from the train's smokestack.17

During the western trip, Edison talked to other scientists about new discoveries in the field of electric lighting. Edison had toyed with lighting experiments before, but other projects intervened. Even before his train returned to Menlo Park, he had decided to take up the problem again. Much of the attraction was financial. In an interview in April 1878 Edison had said of the phonograph, "This is my baby, and I expect it to grow up to be a big feller and support me in my old age." He soon learned, though, that the phonograph was a solution without a problem: Everyone recognized its brilliance, but no one could figure out what to do with it. Edison imagined it as a tool for business dictation, but the machine was temperamental and slow to catch on, and the market for recorded music was a decade away. In 1878 the phonograph did not appear likely to turn a profit anytime soon.18

With electric light, on the other hand, the business plan was clear. People needed ways to dispel the darkness, and the existing technologies—candles, illuminating gas, kerosene lamps—were far from perfect. A good electric lamp might well support the inventor in his old age.

*Western Union sued Atlantic & Pacific over rights to the quadruplex, and the dispute was resolved only by the merger of the two companies in 1877.