Edison and the Electric Chair: A Story of Light and Death - Mark Essig (2005)

Chapter 13. Condemned

ALTHOUGH the electrical execution law took effect on January 1,1889, newspapers had to wait until May for the year's first capital murder trial. It took place not in Manhattan, the state's murder capital, but at the opposite corner of the state. Buffalo—the city where Lemuel Smith became the first American to die from the shock of a dynamo, where Alfred Southwick conducted the first tests in electrical killing, and where George Westinghouse installed his first alternating system-was also home to the first man sentenced under the electrocution law.

Mary Reid owned a big square cottage on South Division Street in Buffalo. She lived with her two young daughters at the front of the house and rented four small rooms in the back to William Hort, his wife, Tillie, and their four-year-old daughter, Ella. At about eight o'clock on the morning of March 29,1889, as Mrs. Reid washed dishes, she heard a shrill scream from the back of the house, then the hollow thwack of someone chopping wood, then a few low moans, then silence. She walked toward the back of the house and called out, but she received no reply. She then walked outside, where she saw Mr. Hort walking toward her, his hands smeared with blood.

"I have killed Mrs. Hort," he said.1

Mrs. Reid gathered her children and fled to tell a neighbor, a bookbinder named Asa King, who walked to the Hort residence and opened the kitchen door upon a horrific scene. The tables and chairs were overturned, broken dishes and an uneaten breakfast scattered across the floor, blood spattered across the walls. Tillie Hort was on her hands and knees, rocking back and forth and moaning quietly. Her long hair, matted with blood, swept down to the floor. Not far away was a bloody hatchet. William Hort had returned inside and was standing at the back of the kitchen, wiping his bloody hands on a cloth. King urged Hort to go for a doctor, but he refused. Instead, Hort stepped over his bleeding wife, went out the door, walked down the street to Martin's saloon, and ordered a beer. King, who had followed, told the saloon keeper that Hort had killed his wife. Refused his drink at Martin's, Hort walked dowrn the street to the next saloon, where he had just taken the first sip of a beer when a Buffalo patrolman arrested him.

Mrs. Hort was rushed to Fitch Hospital. She had ugly gashes on her left shoulder, right arm, and right hand, but her head suffered the worst damage. Doctors counted twenty-six cuts in her skull, varying from one to four inches in length. They removed the loose shards of skull and tried to stop the bleeding, but there was little they could do. Tillie Hort died seventeen hours later.

Even before she died, reporters and the police had been piecing together the story of her life. One of the first things they learned was that Mr. and Mrs. Hort were not married. In fact, neither of them was legally named Hort: He was William Kemmler, and she was Tillie Ziegler. About a year and a half before, Kemmler was living in Philadelphia and working as a huckster, selling food from a wagon. One night, while drunk, he married a woman he knew only slightly. Desperate to escape the situation, he sold his horse and wagon and disappeared. He did not leave town alone. Matilda Ziegler, who was related to Kemmler by marriage, was unhappily wed to a man whose "fondness for fast women" had resulted in his contracting "a loathsome disease." She bundled up her young daughter, Ella, and ran away to Buffalo with Kemmler. They called themselves the Horts and settled down as man and wife. William—known to his friends as "Philadelphia Billie"—took up work as a huckster again and prospered. Before long he owned four horses and three wagons and employed a handful of men and boys who helped him peddle fruit, vegetables, butter, and eggs. He made more than enough money to support his small family, but he drank too much, and his fights with Tillie sometimes kept the neighbors awake.2

William Kemmler and Tillie Ziegler

After his arrest, the police supplied Kemmler with a glass or two of brandy, and he admitted to the crime. Illiterate, he signed his confession with an X. When the trial started a month later, on May 7, 1889, the courtroom galleries filled with what a reporter described as "the usual crowd which hastens to a murder trial as to a picnic." Kemmler entered the courtroom looking uncomfortable in a new brown suit. A slender man of twenty-eight, he had been deeply tanned from long days peddling vegetables, but a month in jail had bleached him out. From the moment of the arrest, newspapers made a point of saying that Kemmler took the situation "cooly" and expressed neither defiance nor remorse. He was similarly inscrutable during the trial, spending most of the time gazing at the floor, his elbows on his knees, snapping his thumb as if shooting marbles. Often his head sank so low that it rested on the table in front of him. The Express believed that Kemmler's calm indicated not murderous coldness but "mild-eyed imbecility."3

If Kemmler's sorry appearance inspired sympathy, the testimony quickly dispelled it. The prosecution took only a day to present its case. Kemmler's motive for murder was jealousy. He believed that Ziegler had become "too familiar" with one of his employees, a Spaniard named John "Yellow" DeBella. Mary Reid and Asa King described the gruesome crime scene and testified that Kemmler had admitted his guilt. A doctor from Fitch Hospital detailed Tillie Ziegler's wounds and handed the jury a paper box containing seventeen skull fragments removed from her head before her death. Dr. Roswell Park, later a noted cancer researcher, had consulted on Ziegler's case. When a defense attorney bizarrely asked whether Tillie Ziegler was "good-looking," Park grimly replied, "Not as I saw her."4

Kemmler's attorney did not bother to dispute much of the evidence against him. "We will not ask you to acquit this man," the lawyer told the jury, "for I believe it would be monstrous to turn loose upon society a man with such propensities as his." He argued, though, that Kemmler was a hopeless drunk and therefore incapable of premeditation. If this was so, the defendant deserved life in prison rather than death. A friend testified that he had never seen Kemmler not drunk, and an employee reported that while peddling "it was their custom to take in with strict impartiality all saloons on the route." One of Kemmler's employees reported that he got drunk with Kemmler on the afternoon before the murder. "He started in on cider and wound up on whisky," the man said. "We had some eggs to sell, but we were all too drunk to sell eggs." Asked to speculate on Kemmler's condition the following day the man reported that Kemmler usually was "shaky" when he woke up, and that the two of them "always went for a drink in the morning." The beer Kemmler bought at about half past eight after killing his wife was part of his morning routine.5

On May 9, the third day of the trial, the prosecution and the defense attorneys made their closing statements, and the judge sent the jury to its deliberations. At ten that evening, when the court reconvened, the members of the jury had not reached a verdict, so the judge sent them out for a full night of deliberations. The next morning the weary jury members filed back into the courtroom and announced that they remained deadlocked. Rumor had it that the panel was evenly divided between a verdict of first- and second-degree murder. The judge told the jury that to be responsible for his crime a man need not be intelligent; he simply must understand the nature of his act. If a guilty verdict required the defendant to be intelligent, the judge impatiently explained, then "half the human family would be exempt from the consequences of crime." The judge's instructions had the effect he so obviously desired. Within two hours, the jury found Kemmler guilty of murder in the first degree.6

Several witnesses testified that immediately after the crime, Kemmler said, "I have done it, and I am ready to take the rope." But New York State, of course, no longer hanged criminals. The court ordered that Kemmler be executed with electricity during the week of June 24,1889. The prisoner appeared sanguine in the face of death. He told his keeper that he "dreaded the long drop and thought he'd rather be shocked to death."7

KEMMLER WAS TRANSFERRED to the state prison in Auburn to await his death. In early June, however, newspapers reported that he would appeal his sentence on the grounds that the new execution method was unconstitutional. His case was to be handled by a new attorney, W. Bourke Cockran, one of the most respected and feared litigators in New York. Born in Ireland and educated in France, Cockran had been practicing law in New York since the late 1870s. His oratorical skills brought him to the attention of New York's Tammany Hall Democrats, who secured him a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives in 1887. Cockran resigned after just one term to return to his lucrative private practice.

Cockran was far too expensive for William Kemmler, and many newspapers charged that George Westinghouse was paying his fees. It was a logical assumption, because overturning the new law would foil Harold Brown's plan to use Westinghouse generators for executions. Cockran had never worked for Westinghouse before, but it was known that Westinghouse's chief attorney, Paul Cravath, often hired Cockran to handle litigation for him.8

Bourke Cockran

Cockran denied any connection. "I wish you would say that I am not retained by the Westinghouse Electric Company on behalf of Kemmler," he told a reporter. "I believe the law to be unconstitutional and inhuman, and deem it due to the honor of the State and for the welfare of justice that it should be tested. No electrical company has retained me, and I am doing this without hope of financial remuneration." Few believed the statement. The New York Times bluntly stated that Cockran was motivated not by "a desire to save Kemmler" but by "the objection of the Westinghouse Company to having its alternating current employed for the purpose" of execution.9

WESTINGHOUSE HAD ACCUSED Edison of promoting electrical execution to damage the market for alternating current; after Kemmler's trial, Westinghouse found himself accused of attempting to defeat the execution law in order to defend his system. It was clear to all observers that competition between the two firms had grown ferocious since the battle of the electric currents had started a year before.

Westinghouse was not timid about the methods he used to ensure success, and, even by the freewheeling standards of the time, he earned a reputation as an unscrupulous businessman. "We do not like the method of doing business of the Westinghouse Co.," a smalltown electrical entrepreneur reported, and many agreed with him. In 1888 the Thomson-Houston company decided to begin producing street-railway equipment. To do so it needed to revise its corporate charter, which required a special act of the Connecticut legislature. Westinghouse interests, fearful of a new competitor in the railway business, lobbied strongly against the bill. Edward Johnson of Edison Electric considered the Westinghouse effort grossly unjust and helped Thomson-Houston win the charter revision. "The methods of the Westinghouse people are, as we know, of the most unfair and undignified character," wrote Elihu Thomson, the cofounder of Thomson Houston.10

A year later Thomson was outraged to learn that George Westinghouse had been awarded a broad patent on an alternating-current meter that he had not even invented. Whereas Thomson's own application for a meter patent—filed much earlier than Westinghouse's—gathered dust in the government office for ten months, Westinghouse's was issued only two months after filing. As Thomson saw it, "the Patent Office could only have allowed this patent through corruption or bribery of some kind." According to a banker who knew all the major players in the industry, Westinghouse "irritates his rivals beyond endurance." Charles Coffin, the president of Thomson-Houston, complained of Westinghouse's "attitude of bitter and hostile competition."11

Thomas Edison had a particular reason to resent Westinghouse, who made a habit of appropriating Edison's inventions for his own use. Edison told a reporter, "It … always made me hopping mad to think of the pirates in the electric business, not merely stealing the radical inventions which made the lamp possible, but taking advantage gratis of the long line of thousands of experiments which I had made night and day for a couple of years."12

Edison Electric was embroiled in two crucial suits with Westinghouse. In one, it defended its basic patent for the incandescent lamp Edison invented in 1879. Although the suit was originally filed against the U.S. Electric Lighting Company in 1885, by the time it came to a hearing in 1889, that company had been purchased by Westinghouse. In the other suit, Edison Electric was the defendant. The Consolidated Electric Light Company had sued Edison Electric, claiming that Edison's lamps violated a patent, owned by Consolidated Electric, on incandescent lamp filaments made from paper. In 1888 George Westinghouse gained control of Consolidated, adopted the suit as his own, and pressed it with vigor. Of the hundreds of lawsuits filed in the first decades of the electrical industry, only these two carried real significance. In both cases, Edison defended his most prized invention—the lightbulb—against infringement by George Westinghouse.13

Edison took the matter personally. Early in 1889, as the patent battle intensified, a mutual friend of Edison and Westinghouse tried to broker a peace, urging Edison to visit Westinghouse in Pittsburgh. Edison would have nothing of it, explaining that Westinghouse's "methods of doing business lately are such that the man has gone crazy over sudden accession of wealth or something unknown to me and is flying a kite that will land him in the mud sooner or later."14

At the time Westinghouse's kite was flying high, with his business growing far more quickly than Edison's. Some Edison Electric officials believed that they were losing ground to Westinghouse because their company was poorly organized. At the start of 1889 the Edison electrical business was still fragmented into several distinct firms, including Edison Electric Light Company (the patent-holding company) and the manufacturing enterprises (the Tube Company, Lamp Company, Machine Works, and Bergmann & Company). In April these firms were merged to form a new company called Edison General Electric, with Henry Villard as president and Samuel Insull—who earlier had served as Edison's secretary and as manager of the Machine Works—as vice president. (Edward Johnson resigned the presidency of Edison Electric and became the president of the electric railway division of the new company.) Edison General, it was thought, would operate more efficiently and command enough capital to push rapid expansion of the Edison system. A few dissenters within the company suspected that the consolidation failed to correct the company's basic problem: the lack of an alternating system to compete with Westinghouse's. 15

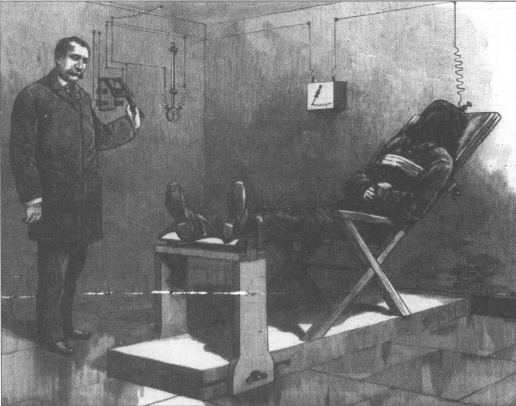

JUST AFTER the Buffalo jury convicted William Kemmler in May 1889, Harold Brown provided the first public description of the execution apparatus to the New York Star: "There will be a strong oaken chair, of the reclining make, in which the condemned will sit, and electrodes for the head and feet. The former of these electrodes consists of a metal cap, with an inner plate covered with a sponge that has been saturated with salt water, which is to be fastened on the condemned man's head by means of stout straps held by another strap around the body under the armpits. The other electrode is simply a pair of electrical shoes tightly laced on the convict's feet." A few weeks later illustrations of the chair appeared in the New York Daily Graphic and Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper. 16

Brown apparently believed that revealing these details would help his cause, but they had the opposite effect. The New York Evening Post explained that it originally had backed the law in the belief that "the victim would die with the touch of a wire or a knob." As the Post saw it, the myth of the simple and tidy execution was exploded by these new descriptions of the apparatus, in which the prisoner would "be seated in a formidable-looking chair, have his feet encased in shoes which contain damp sponges, have another sponge placed on his head, and his head clamped down with metallic bands." The first exe-cution "will doubtless be very interesting to the scientists," the Postclaimed, but its humanity was in doubt.17

Harold Brown released this illustration of his proposed electric chair in May 1889, not long after winning the state contract to supply execution apparatus.

Electricians and doctors—those who knew most about the balkiness of machines and the resilience of the human body—had first expressed reservations about the law the previous summer, and their doubts had only grown. "The question is really and solely one of aesthetics," the Medical Record wrote. Although electricity might kill quickly, it was not "humane, or civilized, or even scientific, to strap a condemned prisoner to a chair and throw him into a convulsion, or possibly burn the top of his head off." Although the popular press at first had praised the new law as a great leap forward for civilization, many editorial writers got cold feet as the date of the first execution approached. The Buffalo Express, Philadelphia Bulletin, St. Paul Pioneer-Press, Albany Argus, New York World, and New York Herald formed a chorus of opposition to the new law. A World story noted Harold Brown's links to the Edison laboratory under the headline "Thomas A. Edison Said to Be Behind the Plan to Use the Alternating Current in the Death Penalty in Order to Bring it into Disrepute." The Tribune, which originally had supported the law, now predicted that the first execution would be "distressingly bungled." The Sun went a step farther: "The only thing to do is to repeal the law." Because many suspected that the law would be declared unconstitutional, murder trials across the state were put on hold pending a judicial decision.18

The growing opposition to electrical execution pleased Bourke Cockran. In June he argued Kemmler's case before S. Edwin Day, the Cayuga County judge whose courtroom was just a few blocks away from the cell where Kemmler awaited his death. Far from being a humanitarian reform, Cockran said, electrical execution constituted cruel and unusual punishment and therefore violated both the state and federal constitutions. No one had ever killed with electricity deliberately, Cockran explained, and so no one really knew what would happen to the first victim: "We hold that the state cannot experiment upon Kemmler."19

By the summer of 1889 there were so many charges of backhanded dealings and shoddy science that most people did not know what to think of electrical execution. The courts charted a deliberate course. In response to Kemmler's appeal, Judge Day ordered hearings to gather evidence on the question of whether electrical death violated the constitutional prohibition of cruel and unusual punishments. Supporters and opponents of the law, who had sniped at each other in the press for over a year, now would meet in open debate, to be examined and cross-examined by attorneys for the state and for William Kemmler. From the crucible of the adversarial legal system, it was hoped, the pure light of truth would emerge.