Edison and the Electric Chair: A Story of Light and Death - Mark Essig (2005)

Chapter 11. "A Desperate Eight"

ALTERNATING CURRENT was much On Edison's mind during the summer of 1888. The French syndicate's grip on the world copper supply had not loosened, which meant that the price of conductors for Edison's system remained high. The Thomson-Houston Electrical Company, which previously sold arc lighting and direct-current incandescent equipment, began selling an alternating system as well, giving Edison a second major competitor in incandescent lighting. George Westinghouse continued to win most of the business in small towns, and he was doing well in cities, too. An Edison agent in one town wrote to describe "a desperate fight between the Westinghouse Co. and Edison" to win a lighting contract. Francis Upton, Edison's longtime associate, urged him to build a new system that could transmit greater distances and therefore compete "in places where now we have no chance, or where the Westinghouse Alternating System will be used."1

Among the drawbacks of the alternating system were the lack of a motor and meter. By March 1888, however, word leaked out that Westinghouse engineers had produced a meter, which would allow their current to be sold more efficiently. Even more alarmingly, in May the U.S. Patent Office issued five patents for an alternating-current motor to Nikola Tesla, a brilliant young Serbian inventor who earlier had worked for Edison. George Westinghouse snapped up the patents and put Tesla on his payroll. The motor was not yet ready for market, but the Edison interests worried that soon enough they would lose another major advantage over the competition.2

Early in 1888 Edward Johnson, Edison Electric's president, printed hundreds of copies of a long, scarlet-covered pamphlet titled A Warning firom the Edison Electric Light Company and mailed them to reporters and officials of local lighting utilities that had bought or were considering buying equipment from Edison's rivals. Johnson cited numerous violations of Edison patents—including the incandescent lamp—by Westinghouse, Thomson-Houston, and other companies, and he cautioned buyers of these rival systems that they might get stuck with worthless equipment if Edison's patents were upheld. The Edison system, he added, was far more efficient than its alternating-current rivals. Johnson also issued a grave warning concerning the dangers of alternating current. "Death-dealing" high-tension currents had killed dozens, Johnson reported, and he reprinted excerpts from newspaper articles about electrical accidents. The Edison system, on the other hand, had a "glorious record" without "a single instance of loss of life."3

Manufacturers of alternating current rose to its defense, and in the late spring of 1888 electrical societies staged heated debates between partisans of each system. "It is no longer a question of discussing the pros and cons in amicable conclave," the journal Electrician reported, "but of fighting tooth and nail." "The battle of the currents," as it became known, had begun.4

Just as the battle was heating up, George Westinghouse made a gesture of peace by writing to Edison. "I believe there has been a systematic attempt on the part of some people to do a great deal of mischeaf [sic] and creat [sic] as great a difference as possible between the Edison Company and The Westinghouse Electric Co., when there ought to be an entirely different condition of affairs," Westinghouse wrote. Perhaps, he proposed, Westinghouse Electric could make "some sort of arrangement with the Edison Company whereby harmonious relations would be established."5

Edison wrote a terse letter of reply. "My laboratory work consumes the whole of my time and precludes my participation in directing the business policy" of the company, he explained. This was not true, for Edison was actively involved in Edison Electric policy—he simply saw no reason to accept Westinghouse's offer. Because Edison believed his own lighting system was safer and more efficient, he expected victory and saw no reason to call a truce.6

In the spring and summer of 1888 the Edison and Westinghouse companies argued bitterly over the relative efficiency, reliability, and versatility of the two systems: which converted mechanical to electrical energy with the least loss; which was less liable to break down; which could provide power to sewing machines and elevators as well as lamps; which could serve houses in far-flung districts as well as urban centers. These were arcane and technical matters that remained confined to the dry pages of technical journals. But one issue—danger-had distinct popular appeal. In 1888 the daily newspapers reported an increasing number of accidental deaths from high-voltage alternating current. A Cleveland man died while adjusting a lamp at a theater, and in upstate New York a light company manager died while fixing the carbon on an arc lamp. In New York City, one lighting utility engineer received a fatal shock while oiling a dynamo, a second while cutting a wire that interfered with fire-fighting equipment, a third while demonstrating to a friend that shocks did not affect him.7

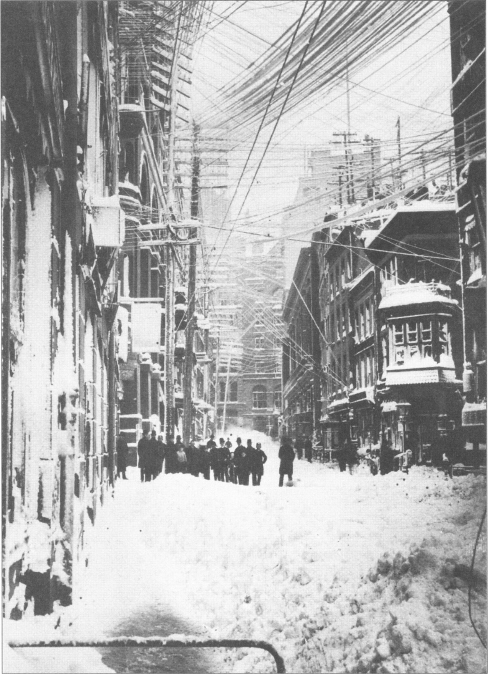

Most of those who died worked in the industry, but electricity posed a threat to the public as well. To see the source of the danger, pedestrians in New York City needed only to look up in the air. By the late 1880s Manhattan hosted nearly a dozen electric light utility companies, which included Harlem Lighting, Manhattan Electric, Mt. Morris Electric, North New York Lighting, Brush Electric Illumi-nating, United States Illuminating Company, Safety Electric, and Ball Electrical Illuminating. Edison Illuminating remained the city's primary supplier of incandescent lighting, its system now stretching as far north as Fifty-ninth Street, while the other companies were primarily in the business of supplying high voltage to arc lamps on city streets. In addition to the lighting firms, there were countless providers of telegraph, telephone, stock quotation, and fire alarm services. Whereas all of Edison's wires were buried underground, the wires of the other companies were strung overhead on tottering poles-some of which carried more than a dozen cross-arms and several hundred wires—or looped across the facades and over the rooftops of buildings.

Bad insulation made many of these wires unsafe. One electrician explained that the most common wire-coating material provided "as much value for the purposes of insulation as a molasses-covered rag." The better insulations were compounded of rubber, gutta-percha, tar, pitch, asphalt, linseed oil, and paraffin, but not even these could long survive the rigors of wind, rain, and high-pressure current. Some arc light cables carried 6,000 volts, far more pressure than the insulation could bear. Poorly insulated high-voltage lines were strung across tin roofs—creating hundreds of square feet of lethal metal surface—or placed just under windows, within easy reach of building occupants. About a third of the overhead wires were "dead," abandoned by their owners and left for years, stripped of insulation and draped across live wires. A drooping bare wire could saw through the insulation of even a brand-new line, and when metal touched metal, whatever the wires carried—human voices on the telephone, telegraphic dots and dashes, or sizzling electric current—veered off on a new path.8

Major cities in Europe required that all electric light wires be placed in underground conduits, and Chicago followed the same course. New York, however, allowed what an electrical journal called "aerial freebooting," in which wires were strung with "absolutely no official supervision." In 1884 the New York State Legislature passed a law much like Chicago's, requiring that all wires be placed in underground conduits. The lighting and telegraph companies, however, ignored the law, so the following summer the legislature created the Board of Electrical Subway Commissioners to enforce the burial of wires. As with much governmental action at the time, incompetence and corruption delayed the work. The law granted an exclusive contract to build the underground conduits to the Consolidated Telegraph and Electrical Subway Company, which was controlled by friends of the subway commissioners. The company's officers dithered in the digging of trenches, and their cronies on the subway commission were not inclined to hurry them along.9

In the late 1880s thousands of telegraph, telephone, and electrical wires ran above New York's streets, posing a danger to the public.

The delays pleased the lighting utilities. They resisted placing their wires underground because they would have to rent space in the conduits, and because underground wires required more expensive forms of insulation. This relentless pursuit of cost savings also discouraged the companies from conducting routine maintenance or installing safety devices that would have protected the public from overhead wires. In 1887 the legislature tried to force the issue with a stronger law that replaced the subway commissioners with the Board of Electrical Control and named New York's mayor as a member. After underground conduits were ready, companies would have ninety days to put their wires in them. When that time expired, the electrical board was to cut down any overhead wires that remained. Finally, by the spring of 1888, a few telegraph and light wires began to go underground.

But there was one notable holdout. The United States Illuminating Company, an arc lighting firm that used alternating current, refused to bury its wires or even maintain them properly. The firm challenged the law in court, insisting that its lines were perfectly safe and required neither burial nor regulation.10

That position became increasingly difficult to defend. In April 1888 a boy peddler died on East Broadway after touching a downed telegraph wire that fell across a high-tension light wire. Later that month a young clerk died in front of his uncle's store after touching a low-hanging arc lamp wire. In May a lineman for Brush Electric died from a shock while working outside a building on Broadway. All of those fatal wires carried alternating current.11

When asked his opinion of the best method of executing criminals with electricity, Thomas Edison replied, "Hire them out as linemen to some of the New York electric lighting companies."12

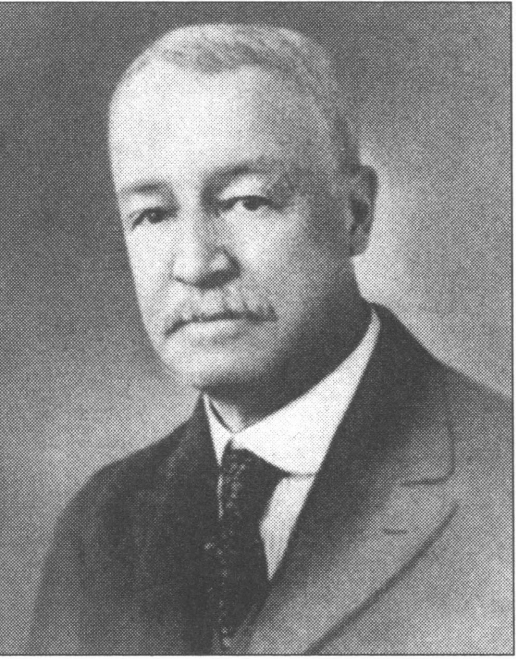

Harold Pitney Brown

WITH THIS CLUSTER of three deaths in New York, the debates over high-voltage current jumped from the pages of electrical journals to the mass-circulation daily newspapers. On June 5—one day after Governor Hill signed the electrical execution bill into law—the New York Evening Post printed a letter from an obscure electrician named Harold Pitney Brown. Just thirty years old, Brown had a decade of experience in the electrical industry. In 1877 he had started working for Western Electric in Chicago, which manufactured a wide variety of electrical devices, including medical apparatus, telegraph and telephone equipment, and an "electric pen"—a sort of early mimeograph—invented by Edison. During the early 1880s Brown installed arc lighting plants for Brush Electric, and by 1888 he was describing himself as an independent electrical consultant. Brown's boss at Western Electric had been a man named George Bliss, a close associate of Edison's who 140 became a fierce opponent of Westinghouse in the battle of the currents. Brown, it turned out, agreed with his former boss.13

In his letter to the Post Brown defended those who wanted to ban high-voltage overhead lines in New York, but he also opened a more general attack on alternating current. He echoed the arguments of Johnson's Warning, but he expressed them in incendiary language. Alternating current was so dangerous to human life, Brown claimed, that it could "be described by no adjective less forcible than damnable." The only reason to use it was to save on copper costs: "That is, the public must submit to constant danger from sudden death in order that a corporation may pay a little larger dividend" An alternating-current wire above a New York street, Brown warned, "is as dangerous as a burning candle in a powder factory." Brown advised New York City's Board of Electrical Control to limit the transmission of alternating current to no more than 300 volts—a restriction that would effectively ban it altogether, for without the advantages afforded by high-voltage transmission, it could not compete effectively with direct current. Brown was not troubled by this possibility, because he considered direct current far preferable: "a continuous current of'low tension,' such as is used by the Edison Company for incandescent lights, is perfectly safe."14

Manhattan's Board of Electrical Control suddenly found itself at the center of a nasty fight over electrical safety. At a July meeting of the board, defenders of alternating current—most of them employees or allies of Westinghouse—vilified Brown. One described Brown's letter as "a villainous budget of perversions of fact," while another claimed Brown was "entirely ignorant" of electrical technology. A Westinghouse vice president cited Edward Johnson's circulars and Brown's letter as evidence of the "desperation of opposition companies." Brown's attack, one critic claimed, was "made rather with a view to injuring rivals than with a purpose of protecting the 'dear public.'"15

But the critics did not stop at impugning Brown's knowledge and motives. Whereas Brown had claimed that direct current was much safer than alternating, they argued that just the opposite was true. "The alternating current," one claimed, "while disagreeable, is far less dangerous to life than a direct current of the same tension," and another insisted, "I have myself received 1,000 volts without even temporary inconvenience." As long as the current is less than 1,100 volts, one man said, "no fatality can occur, or serious inconvenience result." One electrician went so far as to claim that a shock could be good for people. When a person was felled by a lethal direct-current shock, he said, "the passage of an alternating current through the body has been very efficacious in restoring life."16

These electricians did not explain why they believed alternating current was less dangerous. Brown and his allies, on the other hand, put forth a theory to justify their stance. The dangers of electricity, they said, lay not in the current itself but in its interruptions. Direct current, flowing smoothly in one direction, did little damage, while alternating current, which changed directions many times a second, ripped and tore at the body's tissues. "It is the rapid succession of shocks that kills," Brown wrote in his letter to the Post, "while a single steady impulse of the same intensity would do little damage."17

Brown's letter and the responses to it revealed a dispute that had not yet been resolved by experimental evidence: At a given voltage, which was more dangerous, alternating current or direct?*

To prove the alternating forces wrong, Brown needed allies and equipment. "I therefore called upon Mr. Thos. A. Edison, whom I had never before met," Brown later explained, "and asked the loan of instruments for the purpose, which could not be obtained by me elsewhere. To my surprise, Mr. Edison at once invited me to make the experiments at his private laboratory."18

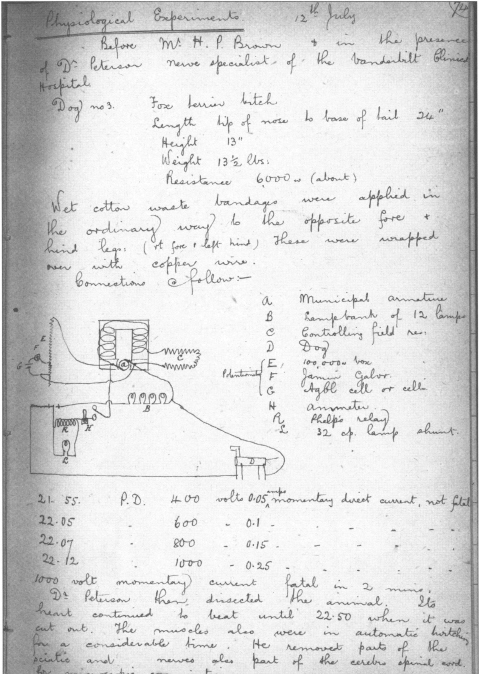

EDISON'S EXPERIMENT for the World reporter in June was an unsystematic demonstration, with no records kept. In July experiments of a different sort took place. The key participants were Brown, Arthur Kennelly, and Dr. Frederick Peterson, a specialist in nervous diseases who would later become the president of the American Neurological Association. The experiments took place under carefully controlled conditions, and Kennelly kept meticulous records in the official laboratory notebooks. Over the next year several dozen animals would die at the Edison laboratory to test the dangers of electricity. These experiments constituted the first scientific researches into killing with electrical generators.19

On July 12 Kennelly and Brown wired a fox terrier to a direct-current dynamo, and the dog survived momentary shocks of 400, 600, and 800 volts. Finally, at 1,000 volts, it died. The second subject, a half-breed bulldog, died almost immediately after receiving a two-second shock of 800 volts alternating current. A few days later a half-breed shepherd was given 1,000 volts direct current, then, in succession, shocks of 1,100,1,200,1,300, and 1,400 volts. At each shock, Kennelly jotted in his notebook, the "dog yelped once but not much hurt." The shepherd was released. Next a "black mongrel" was subjected to increasing jolts with alternating current, and Kennelly recorded the grim results: at 300 volts, "dog howled for about 1 minute & struggled violently"; at 400 and 500, "dog yelped and struggled"; at 600, "dog yelped and groaned. Died in 90 seconds."20

On July 17 Kennelly killed a "yellow mongrel" with 500 volts direct current, with the electrodes attached to the dog's legs, as they had been in all the earlier experiments. Kennelly then applied 300 volts alternating current to the ears of a bull terrier. The dog showed little effect while the current was on, but when it was cut off, the animal bled from the eyes and appeared to be in great pain. Kennelly then "hastened to apply the whole power of the machine in order to terminate his sufferings."21

The dogs that died in these experiments had been bought from neighborhood boys at twenty-five cents a head. The Orange area was soon depopulated of strays, and Edison went looking for a new supply. Back in April he had received a letter from Henry Bergh, the president of the ASPCA, who had heard about the Buffalo SPCA's use of electricity to kill strays and wanted Edison's advice on the matter. The inventor had recommended "a small alternating machine." In July it was Edison's turn to ask a favor.22

A page from the laboratory notebook of Arthur Kennelly, Edison's chief electrician, showing a circuit arrangement for one of the experiments on dogs.

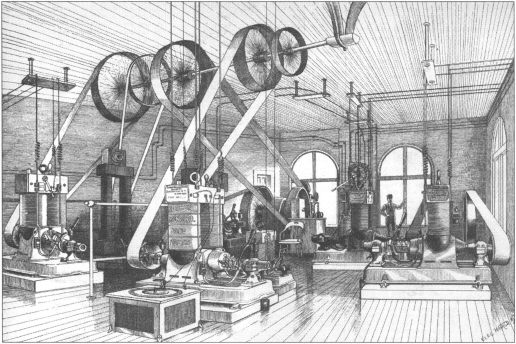

The Edison laboratory's dynamo room, where the dog-killing experiments took place.

"I have lately been trying various experiments on dogs with a view to finding how great a pressure and quantity of electricity it takes to kill them," Edison wrote to Bergh. Although he knew the pressure "within certain rough limits," Edison explained, he wanted to fix it more precisely. "Can you therefore aid me to obtain some goodsized animals for these experiments?"23

Bergh indignantly rejected Edison's request as "antagonistic to the principles which govern this Institution." The SPCA's goal was to use enough current "to produce instantaneous and merciful death," whereas Edison's efforts to determine the minimum lethal voltage were "calculated to inflict great suffering upon the animals." Edison, aware from his own experiments of the truth of Bergh's statement about suffering, quickly apologized.24

The experiments continued with dogs obtained in other ways. Most of the tests took place late at night, between ten and midnight. Edison normally welcomed visitors, but he kept these experiments as secret as possible. The lab workers, though, knew what was happening, alerted by the agonized howls of dogs. Edison's men stood outside the dynamo room and peered in through the windows to catch glimpses of the experiments.25

BROWN AND KENNELLY believed they were ready to prove that alternating current was more dangerous than direct, so they scheduled a public demonstration. On the evening of July 31,1888, a crowd of seventy-five gathered in an auditorium at Columbia College in Manhattan. The audience included the best and brightest of New York's electrical community: members of the city's Board of Electrical Control, officers of the Edison and Westinghouse companies, the editors of Electrical World and Electrical Review, and the secretary of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers. Brown, assisted by Kennelly and Dr. Peterson, produced a seventy-six-pound black mongrel. Although it suffered dreadfully, the dog survived successive jolts of 300,400,500, and 700 volts direct current. When given 500 volts alternating current, it "gave a series of pitiful moans, underwent a number of convulsions and died." Brown and Kennelly then prepared to experiment upon another dog, but one of Henry Bergh's ASPCA officers stopped the proceedings. The officer said that "if it was necessary to torture animals in the interest of science it should be done by the colleges or institutes and not by rival inventors."26

Undeterred, Brown scheduled a second demonstration for the evening of August 3. This time Kennelly was not present, nor were the representatives of the Edison or Westinghouse companies. To avoid further interference from the ASPCA, Brown enlisted the assistance of two physicians licensed to practice vivisection. Brown used alternating current to kill three dogs: a black mongrel (killed by 272 volts), a Newfoundland (340 volts), and a Newfoundland-setter mix (234 volts). The doctors then dissected each dog to note the physiological effects of the current.27

"If this sort of thing goes on, with the accidental killing of men and the experimental killing of dogs," the Electrician wrote, "the public will soon become as familiar with the idea that electricity is death as with the old superstition that it is life."28

"We made a fine exhibit yesterday," Harold Brown wrote to Kennelly. "It is certain that yesterday's work will get a law passed by the legislature in the fall, limiting the Voltage of alternating currents to 300 Volts."29

*The danger of an electric current actually depends on the combination of volts and amperes; a high-voltage current is not dangerous if the amperage is low. Published reports on these debates, however, usually noted only the voltage, omitting the amperage measurements.