Chaucer (Ackroyd's Brief Lives) - Peter Ackroyd (2005)

Chapter 3. The Diplomat

![]()

When Chaucer next appears in the historical record, in 1366, he is already in the king’s diplomatic service. In February of that year a warrant for his safe conduct was issued by the king of Navarre, in the name of “Ge froy de Chauserre escuier englois en sa compaignie trois compaignons . ” The nature of this mission by Chaucer and three unnamed companions is not certainly known. It has been suggested that they were travelling to Spain on pilgrimage to the shrine of St. James of Compostella, where they might wear the pilgrim badge of the scallop shell, but this is unlikely. Folk longed to go on pilgrimages, but not in the Lenten season. It is far more probable that they were engaged on a secret mission concerning the affairs of Pedro of Castile; he had aligned himself with Edward III’s oldest son, known familiarly as the “Black Prince,” but was facing an imminent invasion from France. Whether Chaucer was engaged in negotiations with the king of Navarre, or whether he was persuading certain English forces to assist Pedro, is unknown; it is only important to note that at the age of twenty-four he was being entrusted with important and perhaps clandestine diplomatic business. He was a rising member of the royal household, and would move upwards ineluctably through the ranks of valettus and esquire: a “new man,” coming from the world of London merchants and businessmen and financiers, who was also able to position himself within a more ancient and honourable hierarchy of the realm. Yet his position was therefore ambiguous; he was deemed to be one of the gentility, but he was not of aristocratic rank. It might be suggested that as a result he was in the best possible position to observe, and to understand, the social changes and displacements taking place all around him. Some of the Canterbury tales concern these “new men,” and the pilgrims debate the conflicting claims of noble birth or personal virtue as the guarantors of “gentillesse.” It was an abiding preoccupation of Chaucer’s generation.

There were other ways of acquiring royal patronage. Chaucer’s father died in the early months of 1366 and, although his will is not extant, it is inconceivable that his only son was not left some part of a large estate. With the advantage of inherited wealth and property Chaucer found himself conveniently placed to marry Philippa de Roet, herself already a lady in the household of Edward III’s consort, Philippa. In the household accounts there is reference to “Philippe Pan,” which has been construed as “Paon”; Philippa would then be the daughter of Sir Paon de Roet.

The marriage of Geoffrey Chaucer and Philippa de Roet was no doubt what a future generation would call a “career marriage.” It was by no means unusual for members of the royal household to unite themselves even more closely in this manner, in emulation of their employers, and we may see Chaucer’s social life following the established routines of the fourteenth-century court.

A lady of the chamber helps her mistress dress her hair

In the early autumn of that year “Philippe Chaucer” was granted a life annuity of ten marks by Edward III and described as “une des damoiselles de la chambre nostre treschere compaigne la roine ” ; as one of the ladies of Queen Philippa’s chamber, she may have been able to further her new husband’s career and reputation.

Very little is known of the Chaucers’ domestic and familial life. There seems to have been a first-born daughter, Elizabeth Chaucer, who was admitted to the Black Nuns in Bishopsgate Street in 1381 and who later entered Barking Abbey; she disappears into mysterious seclusion. More is known about Thomas Chaucer. He was born in 1367 and at an early age entered the household of John of Gaunt; he remained in courtly service all his life, and rose through the ranks to become a very rich and thoroughly successful man. His daughter—Chaucer’s granddaughter—finally resolved the distinction between the merchant class and the aristocracy by becoming duchess of Suffolk. The lifelong quest of the Chaucers for “gentle” status was finally achieved.

John of Gaunt also interested himself in the affairs of Elizabeth Chaucer, since it was he who paid for her admission to the Black Nuns, a payment that has led some Chaucerian biographers to fear the worst. It has been inferred that both Thomas and Elizabeth were in fact the children of Gaunt by Philippa Chaucer, and that the poet was used willingly or unwillingly to confer legitimacy upon them. It is certainly true that Philippa’s sister, Katherine Swynford, later became John of Gaunt’s official mistress; but any other relationship exists only in the area of speculation. If true, it would immeasurably deepen and complicate Chaucer’s relationship to the social and courtly world; it would also throw an interesting light upon his characteristic irony and detachment. But at this late date nothing is known or can be proven. To all appearances Geoffrey and Philippa Chaucer have all the attributes of a “professional couple” working in harmony, and such an arrangement need not necessarily be at the expense of love, trust and affection.

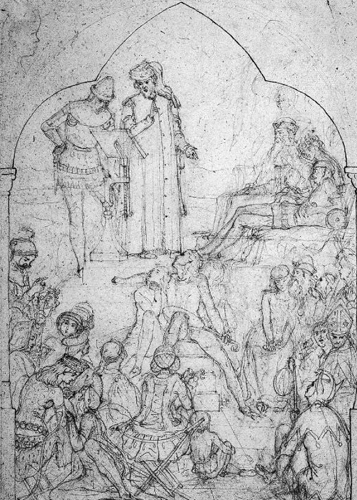

Pencil design for “Chaucer at the Court of Edward III,” Ford Madox Brown’s nineteenth-century vision of the poet at court

Even as he was acquiring a reputation as a skilled negotiator, Chaucer had already made his mark as a skilful poet of the court. By his own account he wrote “many a song and many a leccherous lay.” It is likely that these earliest verses were composed in French for a predominantly French-speaking court; we may imagine the young Chaucer reciting them to a small audience like that portrayed in his Troilus and Criseyde, where three ladies are sitting “withinne a paved parlour” listening to a “geste” or verse story. Indeed a manuscript of contemporaneous French love poems survives, with the notation of “Ch” against fifteen of them. They are sufficiently melodious and inventive for a young and aspiring poet and, if they are indeed by Chaucer, they serve to emphasise that his early work was firmly set upon the model of fashionable French poetry.

The court of Edward III was in many respects itself dominated by French custom. His wife, Philippa, came from Hainault; his mother, Isabella, had been a French princess. The captured king of France had been living in England as a willing or unwilling hostage, and continued all the arts of patronage while in captivity. The verses of Machaut and Froissart, Deschamps and Graunson, were widely circulated; Chaucer met Froissart after the French poet had joined the household of Queen Philippa, and there is some evidence of mutual influence. There is a further connection, which bears testimony to the variously interlinked groups which comprised late medieval society. Philippa Chaucer’s father, Paon de Roet, was a knight of Hainault. From the same principality came Queen Philippa, as we have seen, and Froissart himself. There was, in other words, a Hainault affinity to which Chaucer had an intimate attachment.

Philippa of Hainault, Edward III’s French queen. Chaucer’s wife, also called Philippa, served in her household

So at the beginning of his poetic career Chaucer wrote complaints and roundelays, ballades and envoys, on the themes of love and passion. It was a literature of longing, established by the rules of courtly etiquette and by the laws of fine amour or what in The Legend of Good Women Chaucer termed “the craft of fyn lovynge.” His contemporary, John Gower, records that “in the floure of his youthe” Chaucer filled the whole land with ditties and with glad songs, some of which still miraculously survive in his collected works. Much of Chaucer’s court poetry has disappeared, as the natural result of time and inattentiveness, but poems such as “The Complaint unto Pity” and “A Complaint to His Lady” testify both to what has been called the natural music of Chaucer’s verse and to his mastery of poetic diction. In his early years, too, he was an inventor and an experimenter. He introduced the rime-royal stanza and terza rima into English verse; he was the first to employ the French ballad form, but he changed the French octosyllabic measure into what has become characteristically English decasyllabics:

O verry light of eyen that ben blinde,

O verrey lust of labour and distresse …

He invented the native measure.

Yet there is one achievement that surpasses all of his technical skills. After his first forays into French court verse he chose to write in English for a predominantly courtly audience. He had enough confidence in his own skills, and in his own language, to adopt a native muse. In that sense he can be said to anticipate the rise of English in the fourteenth century. His was a period when the status of the native language was being elevated, and its usage becoming much more widely and securely based; in Chaucer’s lifetime it replaced French as the language of school-teaching. The Anglo-French language, derived from the Norman conquerors, had long dominated social discourse. But the court of Richard II was the first, since the time of the Anglo-Saxons, in which English was the principal language. Everything conspired to render Chaucer the most representative, as well as the most accomplished, poet of his time.

When he began his career as a poet of the court there were obvious examples of English poetry all around him, from the romances of Sir Orfeo and Sir Launfal to the versified manuals and histories of various monkish chroniclers; there was also a fine lyric tradition, both secular and sacred. But there was no tradition of sophisticated courtly poetry in English; Chaucer adapted or assimilated the vocabulary and structure of fashionable French poetry, and effortlessly reproduced them within English diction and cadence. It is a significant achievement for a young poet, and did not go unremarked.

In fact one of his French models, Eustache Deschamps, sent Chaucer a “ballade” a few years later in which he praised him as a “grand translateur.” He was referring in particular to Chaucer’s translation of Roman de la rose, a French allegorical epic on the theme of love. As Chaucer explains in some early lines:

It is the Romance of the Rose,

In which al the art of love I close.

The first section of some four thousand lines was written by Guillaume de Lorris in the early thirteenth century, and it was concluded half a century later by Jean de Meun, a scholar whose narrative of love is embellished by digressions and asides on a thousand different subjects. Chaucer chose to translate only passages written by the earlier poet. It is not clear whether he published his results to the world, but there are unmistakable signs of his ready wit and invention. We can almost see him marshalling his native language into appropriate shape:

Though we mermaydens clepe hem here

In English, as is oure usaunce,

Men clepe hem sereyns in Fraunce.

He also evinces a genuine pleasure in the sensitive calibration between the Romance and Saxon elements of native speech:

Largesse, that settith al hir entente

For to be honourable and free.

Of Alexandres kyn was she.

Hir most joye was, ywys,

When that she yaf and seide, “Have this.”

It can be concluded that Chaucer, even at such an early stage in his poetic life, was possessed by the delights of diversity and variation; he constantly modified his poetic language to accomplish a wide range of effects, and was always intent upon changes of local detail. His tapestries of flowers, and his symphonies of birds, are rich and particular; he loved the art of miniature. When this is combined with vivid theatricality, and the sonority of the high style, then a most complex poetry may be created.

His Romaunt of the Rose is also the first indication that, by the act and art of translation, Chaucer reinvigorated the English language; when later poets celebrated his “eloquence” they were describing his happy ability to incorporate the swelling measures of French and Italian poetry within his own style. Part of Chaucer’s genius lay in translation; we may imagine a poet delighted by the art of the book. By his own account he found half of his experience in reading. What could be more natural for him than to meditate upon a text and slowly to reproduce it within the fabric of his own language?

In this context it may also be possible to begin to understand Chaucer’s somewhat recessive temperament. His literary persona, manifest throughout his writings, is one of embarrassed bookishness; this is often considered to be a pose or device, quite at odds with his successful and prosperous career in the world, but there may be real truth within it. Why would he wish to create it in the first place, if it did not correspond with some powerful persuasion of his own? He chooses to hide behind words. Or, rather, he allows his personality to be dissolved within them. It can be said, for example, that as a translator someone is doing the writing for him. He does not have to claim authority or responsibility for what he is doing. This is of course precisely the tactic which he uses in his poetry; he shifts the blame, if that is the right word, upon his characters in The Canterbury Tales:

For Goddes love, demeth nat that I seye

Of yvel entente, but for I moot reherce

Hir tales alle, be they bettre or werse …

Blameth nat me if that ye chese amys.

He fakes an original source for his Troilus and Criseyde. “Blameth nat me,” he intercedes. “For as myn auctor seyde, so sey I.” It is also the demeanour of the diplomat, presenting his case on behalf of a higher authority. The rhetorical procedures of his verse are in that sense characteristic; they become a device whereby he can conceal himself, ironically or otherwise. Rhetoric informs the texture of his narrative; it does the writing for him. He uses rhetoric so successfully, in fact, that he can detach himself from his poem. And was he also able to detach himself from his public career? Upon the stage of the world, where everyone played a part, it was important to become an accomplished actor.

In June 1367 Chaucer was awarded a life annuity of twenty marks (£13 6s 8d) by Edward III; since he is variously entitled “valettus” and “esquier” in the royal accounts, his rank must remain uncertain. In succeeding years he was also presented with gifts of winter and summer robes, as well as robes of mourning, appropriate to his degree. He was certainly considered valuable enough to be sent on various missions overseas. In the summer of 1368 he was given a licence to “pass” at Dover; it has been suggested that he was travelling to Milan, where Prince Lionel (after the death of his first wife) had just been married to Princess Violante Visconti. He would then have been exposed to the cult of “Franceys Petrak, the lauriat poete,” Petrarch then being resident in the city, but the circumstances of his journey are not definitely known.

It is clear, however, that in the following year he travelled to France in the retinue of John of Gaunt as part of “the voyage of war.” His role in these intermittent and fruitless hostilities, known to posterity as “the Hundred Years’ War,” is not recorded. He did receive, however, a “prest” or payment of ten pounds for services rendered. Yet the association with John of Gaunt is a significant one, attested by the annual grant he was soon to receive from him. John of Gaunt had become duke of Lancaster seven years before, after his marriage with Blanche of Lancaster. Edward III began his slide into credulous old age after the death of his wife in 1369, and as a result Gaunt’s palace at the Savoy became the true centre of court life in England; his powers of patronage were now such that all sought his favour. Another event brought Chaucer closer to Gaunt’s sphere of influence. In 1368, soon after his wedding to Princess Violante Visconti, Prince Lionel died; the rule of the ageing Edward III was increasingly uncertain, and Chaucer had need of new patrons.

He had left, as it were, a calling card. John of Gaunt’s wife, Blanche of Lancaster, died of the plague in the autumn of 1369—at the time when Gaunt himself was still engaged in his “voyage of war”—but on his return to England he instituted a memorial service to be held each year for her in St. Paul’s Cathedral. Some historians believe that she died the year before, in 1368, turning Gaunt’s expedition into a campaign of sorrowful forgetfulness as much as military hostility; but the nature of Chaucer’s response remains the same. He composed a poem of consolation, entitled The Book of the Duchess, which elegantly and prettily extols Blanche’s virtues while at the same time preserving her memory in the freely flowing poetry itself:

Therto she hadde the moste grace

To have stedefast perseveraunce

And esy, atempre governaunce

That ever I knew or wyste yit,

So pure suffraunt was hir wyt.

The tone and diction of the poem claim it for oral delivery and it seems likely that The Book of the Duchess was first recited at one of the memorial services held in the cathedral; it is couched in a respectful but informal tone, as if the poet were on easy if not necessarily familiar terms with Gaunt himself. The work of a court poet in his mid-twenties, whose abilities were already widely recognised, it is presented in the form of a dream vision, a form highly congenial to Chaucer’s imagination which always works by indirection and ambiguity; in dreams there are no responsibilities. When dealing with “high” matters, such as the grief of the duke of Lancaster, discretion was advisable.

The poem itself belongs to the French tradition of dits amoureux, and in particular to Machaut’s Jugement dou Roy de Behaingne. Its opening lines are, in addition, modelled upon the beginning of Froissart’s Paradys d’Amours. Throughout Chaucer’s poetic output, in fact, there will be found wholesale borrowings and appropriations. Half of his work derives from older and earlier sources. Yet we must forget modern notions of plagiarism and parody. One of the guarantees of virtue and sincerity, in a medieval text, lay in the fact that it derived from a greater authority. There was no merit in originality as such, only in the reformulation and refashioning of older truths. Yet The Book of the Duchess is no mere copy of Paradys d’Amours, or of any other of the texts to which it has been compared. The dry beat of Froissart’s verse has become lush and melodious; the prolixity of Machaut’s narrative style has been curtailed. The French preference for delicate rhetorical effects, and the lively expression of sentiment, has been excised in favour of narrative event and plain dialogue. The French sources have been absorbed, in other words, and out of them an English amalgam is created. It is the paradox of Chaucer’s work: the materials are familiar but their expression is novel and surprising. As he said himself, out of old fields comes all the new corn.