Gothic Cathedrals: A Guide to the History, Places, Art, and Symbolism (2015)

CHAPTER 2

USES OF A CATHEDRAL:

From the Feast of Fools to Market and Concert Hall

In addition to the many uses for a cathedral, it might also serve as a place where judicial cases could be heard, a site for colorful theatrical pageants and guild plays, the location of a university graduation, or even as a concert hall for the public. Very much like the modern town hall or civic auditorium, the use of a cathedral largely depended on what the community needed at any given time. The variety of uses, for both secular and sacred purposes, was endless.

Of course, much of the activity in the cathedral, then as now, consisted of religious services, prayers, matins, vespers, the singing of chants, and the servicing the spiritual needs of visiting pilgrims coming to its shrines.

The heart of a medieval town was often a busy, bustling center, and the cathedral as the focal point of a growing town's activities. The cathedral square, the parvis, was often rather small, but as the Middle Ages went by, more structures were added to the cathedral complex itself. On the religious side, these might include ornate side chapels, oratories, sacristies, and additional murals or stained glass windows in a crypt. On the secular side, we might see space for flower merchants shops, crafts booths, food merchants, and so on.

Here in its bustling square, huge crowds would gather for a cathedral's great festivals and feast days, with a “buzz,” an excitement at the time similar to a major music festival or rock concert today. At a medieval cathedral, the devout might choose to mingle and chat with others nearby, or pray alone at the shrine of a favorite saint.

Craft exhibit booths and crowds milling about on the plaza at the famous modern-day Edinburgh Festival in Scotland. (Karen Ralls)

Juggler and fire eater entertains enthusiastic crowd of children, at Edinburgh Festival reception. (Karen Ralls)

A week in the life of a medieval Gothic cathedral

It might seem quite surprising today to conceive of a majestic medieval Gothic cathedral as being anything other than a most solemn place of worship. In fact, it was at times quite the contrary, especially on select feast days. Especially by the later Middle Ages, a different picture emerges. Within a cathedral's walls people often strolled and chatted openly, not hesitating to bring along their pet dogs, parakeets or falcons! On certain days, merchants were allowed to hawk their wares; and, in some cathedrals, they were even permitted to set up shop inside the nave on designated occasions and feast days. Either in or near the cathedral, jugglers would entertain the children, as they often still do at summer festivals.

Amusing for many today to consider is the fact that cathedrals were also known by the clergy to be a rather “notorious” favorite summer rendezvous spots for young lovers. Couples were known to carefully hide themselves during the day so they could remain locked in for the evening. Needless to say, such assignations were greatly irritating to the clergy. Measures often had to be taken to change the locks at certain locales.

Flasks were often confiscated to reduce incidents of “sacred intoxication.”

On the other hand, during the special pilgrimage times—which brought in so many jubilant crowds from far and wide—individuals were allowed to sleep and eat in the cathedral itself. Its heavy doors were bolted shut for the evening and reopened at 6 a.m. the following day. Then the solemn parading past the shrine of the cathedral would take place—if one were lucky enough to get a place in the queue.

Guild painter with mixed colors, depicted in a 14th century encyclopedia, Source unknown

Medieval civic meetings were held regularly in cathedrals. This worked so well so that some towns found it totally unnecessary to even build a town hall. As an important civic center, a cathedral might occasionally be a scene for the resolving of lawsuits or acrimonious town disputes. As mentioned earlier, on a more pleasant note, it might be also serve to host university graduation ceremonies. (1)

A cathedral could also on occasion be the site of everyday business. For instance, the mayor of Strausbourg was known to habitually use his own pew as his official office. At Chartres, wily wine merchants had their stalls in the nave. They were only told to move after the cathedral chapter committee set aside a portion of the crypt for their exclusive use. (2) The Guilds, too, would hold meetings in cathedrals, not hesitating to carefully ensure that their guild's talents and crafts would be on good display in an optimum location to help advertise their professional crafts to the public at certain times of year, much like a major fair or convention center today. Guilds—both parish as well as civic—were also responsible for holding many of the colorful pageants, dramas, and miracle-plays on the major feast days and at Christmas and Easter. Such events were a huge responsibility to undertake, finance, and maintain.

Papermakers guild members at work

Yet all of these various activities did not result in the chaos that one might imagine. The huge scale of many of the Gothic interiors made it possible to isolate conflicting activities quite effectively. At Amiens, for example, the cathedral could house the whole population of the day. Thus, a loud group of merchants hosting a meeting over at the west door area may have been but barely audible in a chapel opening off the choir. Clearly defined zones were set aside for specific purposes by the clergy. The laity were only admitted to the nave and aisles, and occasionally, for a pilgrimage to the tombs, accessible only from the choir ambulatory. The choir itself was reserved exclusively for the clergy—rather typical when only the clergy were viewed as having direct access to God and certain areas of the cathedral. It was not until the Reformation, much later, that the concept of greater powers and far greater access for all of the laity became more widespread.

Medieval guild plays and pageants

The “cinema” of the Middle Ages was the staged, dramatic productions that often took place in the cathedral. Elaborate theatre performances were held on certain feast days, often utilizing symbolism, humor, allegory and mythic elements in their productions, to make their ultimate point.

One of the most colorful events was the consecration of a new cathedral. Such events were often a unique combination of the highly sacred as well as allegorical, and not without a good sense of humor at times. A rather popular way to celebrate was for the bishop to lead a procession towards the new cathedral, attended by all his clergy in full splendor—except for one. This hidden cleric was to play the theatrical role of a so-called “evil spirit”; he would lurk inside the locked doors, lying in wait to outwit and “ambush” the bishop. Arriving before the closed door, the bishop would knock upon it three times with his large, ornately carved staff (called a crozier). The crowd at the procession would then proclaim, “Lift up your heads, O ye gates, and be ye lifted up, ye everlasting doors, and the King of Glory shall come on in.” First there would be total silence, then, a still voice from within would inquire “And who is the King of Glory?” The crowd would roar in response, “The Lord of Hosts, He is the King of Glory.” (3) At this signal, the bolts would slide open, the allegedly vanquished “spirit of evil” character slipping back out into the crowds—not to slink away in defeat, however, but often to join with his fellows in the ensuing lively festivities. At this, the bishop and his procession entered the cathedral for the final, more solemn, sacred consecration ceremony.

Another dramatic pageant took place on Easter Sunday. In some of the guild plays, a dialogue would take place between the Angel at the tomb and the Three Marys. Later the drama was elaborated upon to include the guards in armor (Pilate's men) keeping watch by night and day beside the candlelit tomb on stage. Such scenes would include—a simulated burst of thunder! Then smoke would mark the climactic moment when Christ was said to rise from the tomb. Some of the guilds were very creative in designing such dramatic effects in their productions.

Some cathedrals provided an even more dramatic spectacle at Pentecost, a joyful season. A dove was let down from the high roof above, and as it flew all about the nave, bright flames were meant to represent the very tongues of fire that descended upon the Apostles.

At Beauvais Cathedral, a dramatic enactment of the “Flight into Egypt” is recorded. A procession, headed by a young girl with a baby in her arms and seated upon an ass (donkey), entered the cathedral and advanced towards the altar. Then came a solemn Mass, conventional in every detail—except that the finales of the Introit, Kyrie, Gloria, and Credo ended not with the usual words, but with mock braying of a donkey, echoed by the celebrant himself, using what was known as “the prose of the ass.”

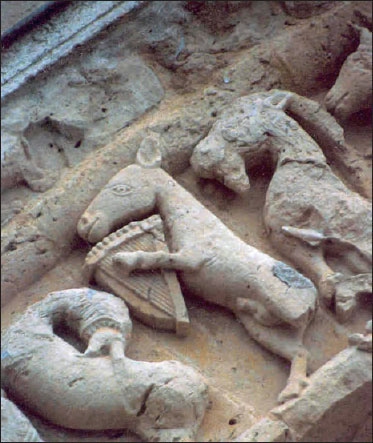

At Rouen cathedral, the annual “Feast of the Asses” went even further, indicating the precise places in the service when the donkey's tail was to be pulled sharply three times—and three times only—so as to achieve perfect synchronization with the priest's thrice-repeated benediction Dominus vobiscum. (4) The rather familiar modern-day children's game of “Pin the Tail on the Donkey” is believed by some folklorists to have derived from this and earlier donkey and ass-related customs from the ancient and medieval worlds. The creative inclusion of a stone carving of a donkey playing a harp was included on the exterior of some cathedrals (i.e, Chartres) and churches, such as at St. Pierre d'Alnay in France.

Stone carving of a donkey playing a harp at the Church of St. Pierre d'Aulnay. (Karen Ralls)

The burgeoning growth of medieval towns, the increasing importance of far more travel and business, the guild movement as a whole, and the spread of education were all factors that tended to create more frequent exchange of ideas, to retain and/or, foster the re-working, of elements of some folk customs and traditions into pageantry. Each influenced the other.

Of course, every religion tends to absorb or attempt to supplant certain aspects of past faiths for various reasons. These might include motives that are downright nefarious. Often, however, adjustments may be made via a more gradual process of mutual influences back-and-forth, or by a process of unconscious assimilation. The medieval Church was certainly no exception to any of this regarding its often quite eclectic festivals, as well as a rather good portion of its music—more so in some areas than others. It all depended on the regional customs, politics, economic situation, and beliefs, which could vary considerably. In actuality, it was a complex situation overall, with many influencing factors.

Perhaps our modern perception of the Gothic cathedral as primarily a house of Light (5) should be broadened to include acknowledgement of the light and inherent wisdom of the often extensive knowledge, local customs, ancient folklore, and unique traditions of the region in which it flourished. Many of these colorful festivities drew huge crowds and were enthusiastically anticipated by the populace as a result of including various elements of earlier customs, songs, or traditions that were important to that particular region. Some of the most colorful and interesting festivities of Christmas and Yuletide, Twelfth Night, the feast of Epiphany, the Feast of Fools, and certain saints' day celebrations often incorporated regional or local elements into their dramas.

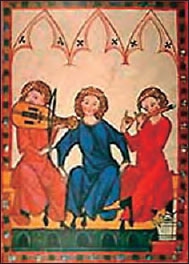

Medieval troubadours; ms. source unknown. (Ani Williams)

Medieval storytellers, jesters, and musicians

In medieval Europe, a variety of great storytellers developed their art. Their superb performances were not intended only for a particular court, an exclusive patron, or a restricted group. The crowds attracted by medieval festivals provided opportunities for storytellers to share their craft with even larger and more diverse audiences. Medieval European storytelling reached “right across the whole of society, with the wit and energy to appeal to an illiterate or semi-literate audience and, at the same time, the subtlety and complexity to satisfy the aesthetes of aristocratic and royal courts.” (6)

And, as we know, by the end of the Middle Ages, nearly everyone had seen or heard the engaging stories and music of the minstrels, jongleurs, and troubadours, and were familiar with the figure of the Fool or “jester.”

The Feast of Fools

Some of the medieval Church's own festivities between Christmas (25 December) and Epiphany (6 January) featured a period of increasingly creative and riotous behavior. The more raucous midwinter “Feast of Fools” is a good example of this. Then, for a limited time, a series of festivities were held where the authorities allowed the entire established social order to be reversed. To such a strictly hierarchal, feudal society, one can only imagine how this day, or period of days, was relished by the congregation! Large crowds would come to the cathedral to participate. For either one day, or sometimes three or more—depending on the locale—we see featured a delightfully outrageous range of characters, such as the Abbot of Unreason, the Prince of Fools, or the now infamous Lord of Misrule. Rules were turned “upside down,” much as they were for certain festivities in ancient times like the Saturnalia in Rome.

Wood carving of the image of a Fool (Stirling, Scotland)

The Feast of Fools, or of Asses, or of Sub-Deacons, was essentially a celebration of the lower clergy of cathedral chapters who held only minor orders. At its inception it was an exercise in Christian humility on the part of the higher clergy, whereby they handed over to the lowest the leadership in religious ceremonies at the time of the New Year feast. Soon, however, it spread backwards into the holy days between Christmas and New Year and began to involve burlesques of the same rite. (7)

In view of the rigid social hierarchy of the Middle Ages, and like its Pagan antecedents, the Feast of Fools could—not surprisingly—become a rather wild affair in some areas during this interlude. Stories of outrageous revelry within the nave were often reported, rivalling the lurid front-page headlines of any modern supermarket “tabloid.” Here is one such account:

Priests and clerks may be seen wearing masks and monstrous visages at the hours of office, dancing in the choir dressed as women, pimps, and minstrels, singing wanton songs and eating black-puddings at the altar itself, while the celebrant is saying Mass. They play at dice on the altar, cense with stinking smoke from the soles of old shoes, and run and leap throughout the church.... (8)

From about the year 1200, the Feast of Fools was quite familiar in France, which remained its stronghold for the rest of the Middle Ages—until its gradual repression in the fifteenth century and its complete abolition in the sixteenth. From France it rapidly spread into Flanders and into Britain. Each country had its own unique way of celebrating the Feast. Some were rather staid, others less so.

The Feast of Fools is mainly familiar to us today from the twelfth century. It seems to have been successively banned and revived depending on who was in power. Even if local churches initially tolerated the Feast—and its lively, colorful processions featuring a “Bishop of Fools” and other characters—it was often ceaselessly combated by the “Church Universal,” depending on the region and locals customs of those performing it. Much of our knowledge of the Feast of Fools comes from the surviving records of the many attempts to suppress it.

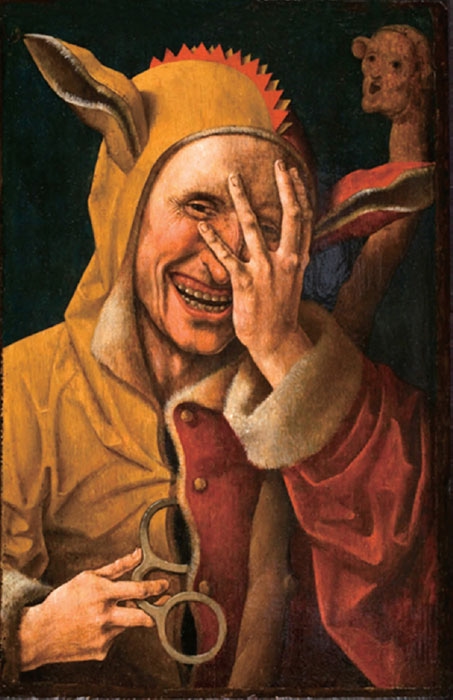

Laughing Fool, Netherlandish (possibly Jacob Cornelisz. van Oostsanen), ca. 1500, oil on panel, Davis museum. (WMC)

Feast of Fools revelry theme. Here, a hare is portrayed riding a dog, on a 13th century medieval tile found at the Friary, Derby, England. (WMC)

The Church was irked by the reported excesses of this festival, yet it continued to embrace certain aspects of the Feast—namely, its theme of humility for the clergy, and especially, its great popularity. Eventually, however, the Church passed strict regulations to help curb some of its excesses. Restrictions were passed in the fifteenth century at various Church councils in France: Rouen, 1435; Soissons, 1455; Sens, 1485; and Paris in 1528. These reforms truncated the usual riotous behavior during certain parts in the ceremony. In England, too, similar reform were instituted. For example, it was specified that the usual shouts of “Deposuit” (“put down, put down”)—i.e., the signal for the canons and senior priests to leave their high stalls so that the lower clergy could then take their places—should now be limited to only “five, and that not more than three buckets of water be poured over the Fool Preceptor at Vespers!” (9)

Although somewhat effective, not all of these rules were obeyed. The strongest resistance would occasionally come from the cathedral Chapter committees. For instance, in 1438, the Feast of Fools was forbidden by the Pragmatic Sanction of Charles VII. But in 1445, when the Bishop of Troyes tried to enforce the ban, he was defied by the Chapters of several churches. They first consecrated a mock-archbishop with a burlesque “of the sacred mystery of pontifical consecration” performed in the most public place in town, and then produced a play which featured Hypocrisy, Pretence, and False Semblance—clearly recognized by everyone as applying to the bishop in question and the two canons who had supported his policy.

At other times, it was the laity who resisted further reform of the Feast of Fools. In 1498, it was with the encouragement of the town authorities that the citizens of Tournai captured some vicars of Notre-Dame and forcibly baptized one of them as “bishop.” It was only an old custom, they pleaded. Probably no one would have objected had not the “bishop” distributed robed hoods with ears to some who would rather have been left out. Those offended souls took their revenge by stirring up the cathedral Chapter to take action. (10)

Though popular resistance was strong, the zeal of Church reformers against the Feast of Fools was not without effect. From the end of the fifteenth century onward, it began to die out in much of Europe.

For an understanding of the record of the Feast of Fools in England, we are fortunate to have the research of the renowned British professor Ronald Hutton and his erudite works, including The Rise and Fall of Merry England. We learn the festival was never quite as major an event as it was in France (with the possible exceptions of Beverley and Lincoln). In fact, no records of the Feast of Fools can be found to occur much later than the fourteenth century.

The very popular tradition of the Boy Bishop in England was first recorded at York in a statue dated 1220. (11) The figure of the “Boy Bishop” seems to have been far more predominant in England than a “Bishop of Fools,” which was more common on the Continent. The Boy Bishop was the mock king of the feast of the choir-boys in a festival very similar to that of the Sub-Deacons. In other words, the Boy Bishop was a child elected by his fellow choir-boys and clad in ornate Episcopal vestments. He was allowed to officiate to some degree in religious activities during December. His presence is recorded in late medieval cathedral documents from Wells, Salisbury, York, St. Paul's, Exeter, Lincoln, Lichfield, Durham, and Hereford.

As Professor Hutton points out, “his activities are most clearly described at Salisbury, where he was elected by the choir-boys from amongst their number. He first appeared in public after vespers (evensong) upon 27 December, a day before the feast of the Holy Innocents...” (12) The 27th of December was also the major feast day of St. John the Evangelist.

The young Boy Bishop led the choristers in procession to the high altar, dressed in full Episcopal robes:

At St. Paul's, the Boy Bishop was chosen by the senior clergy, and was expected to preach a sermon. Three of these have survived, all clearly written by adults but with a great deal of dry humor at the expense of authority. At York the “Bairn Bishop” went to visit noble households and monasteries to collect money for the cathedral. Until the early 15th century, prelates occasionally complained about the degree of disorder associated with the custom but after then, it seems to have been generally accepted and well disciplined. Around 1500, the Boy Bishop processions were also observed in some of the major abbeys which included schools, like Westminster, Bury St. Edmunds and Winchester. (13)

Beltane Mask, a modern artwork in papier maché, by UK artist Rosa Davis.

Boy Bishops would also appear at wealthy collegiate and university churches like Magdalen and All Souls, Oxford and King's, Cambridge. However, at King's and Magdalen, the “bishop” generally presided not at Holy Innocents but on the feast of St. Nicholas, the 6th December. Boy Bishops were usually present in towns or university colleges where there was not also a Lord of Misrule. An exception to this was the royal court, and the household of the fifth Earl of Northumberland's household in London, which had both. (14).

The Lord of Misrule was never as popular a figure in England as he was in France, where the tradition lingered to the end of the fifteenth century. However, when the Lord of Misrule and his cohorts were suppressed and expelled from the churches and cathedrals in France by the efforts of reforming bishops, they were heartily welcomed in French towns, law courts, and universities. There, the ecclesiastic Feast of Fools was succeeded by the secular Societe Joyeuse—associations of young men who adapted the traditional fool's dress of motley colors, eared hoods, and bells. They organized themselves into “kingdoms” under the rule of an annually elected monarch known as Prince des Sots, Mere-Folle, Abbe de Malgouverne, and so on. (15) They celebrated certain traditional customs and these satirical societies sprang up all over France, flourishing mainly from the end of the 15th to the 17th century.

Fool-societies were also organized in other countries. In Germany, for instance, a secular Feast of Fools was held on the banks of the Rhine. Here it was the custom to organize at Twelfth Night a complete court—king, marshal, steward, cupbearer, etc.

In England, the Lords of Misrule or Abbots of Unreason succumbed more easily to the attacks of the reforming bishops. Rather than being the leader of a permanent group of merry Bohemians pledged to continuous criticism of contemporary society, the Lord of Misrule was relegated to being either a temporary court official appointed to provide entertainment for the Christmas holidays, or a leader elected by young students at the Universities or Inns of Court where he would preside over their rejoicings at Christmas and Shrovetide.

Yet, kings and noblemen had a “Lorde of Misrule” or a “Master of Merry Disports” to devise “mummeries” during the Christmas season. And there are references to Lords of Misrule at the Scottish and English courts, especially during the 15th and 16th centuries. From medieval times until the reign of Charles I (r. 1625-1649), there are ample records in England of royal fools, jesters, and dwarfs entertaining their patrons at court and in private homes. (16). When she returned to Scotland with her retinue in 1561, Mary Queen of Scots had a female jester among the professional Fools in her court. This “Lady of Misrule” was listed in the historical record as one Nicola la Jardiniere. It is also known that the Queen awarded her a special jesting outfit—a green dress, trimmed with crimson. (17)

A Lord of Misrule was appointed annually at the court of Henry VII (r. 1485-1509), and probably also in that of Henry VIII (r. 1509-1547). It seems clear that this character was a descendant of the old traditional Christmas lord, or King of the Bean. Even today, Mummers' plays greatly add to the local celebrations of Boxing Day in England and the post-Christmas season. Mummers often provide lively performances at a series of pubs with record crowds in attendance.

Medieval Fools were not only employed by royal courts and official noble households in many European countries, but by city corporations, guilds (both secular and sacred), and burghers (members of the bourgeoisie). The business community hired fools to entertain at various pageants throughout the year. (18) In England, for instance, “fool's tales” and associated folklore developed around certain places, towns, or sites in the landscape. (19)

The phenomenon of the “Christmas Prince” flourished in the colleges of Oxford and Cambridge. His title of Rex Regni Fabarum (King of the Kingdom of Beans) shows his likely connection to this old folk custom. Like the law clerks of Paris, the members of the Inns of Court in London were accustomed to celebrate certain festivals like the Twelve Days of Christmas. During this time they organized themselves as a mock “kingdom” under a Lord of Misrule.

But, as we have noted, all of these later developments of the Lord of Misrule or a Feast of Fools occur totally outside the context of the Gothic cathedral. While the title “Lord of Misrule” in England has often been erroneously assumed today to be primarily one relating to the mock-kings of the midwinter Christmas festivities, this figure was also related to a number of May games and other summer pageants. Thus, he was not solely a part of the Christmastide pageantry. (20)

The history and origins of the Lord of Misrule character may have been drawn from the lively Saturnalia festivals of ancient Rome, as some scholars and folklorists maintain. Lucian, in his Saturnalia, has drawn a vivid picture of the “Liberties of December,” held around the time of the winter solstice—for a short while, masters and slaves would switch places, laws lost their usual influence and force, and a mock “king” ruled the world. The same freedom was allowed at the New Year festival of the Kalends. (The Kalends was the first day of the month in the early Roman lunar calendar, the day of the new moon. It is the root of our word “calendar.”) At the Kalends of December, people exchanged presents, masqueraded, played the fool, and ate and drank to their heart's content.

As one might expect, during the early years of the Christian era, the Church did everything it could in certain locales to stamp out and suppress the celebration of the Kalends. They felt this festival was a form of “devil worship” that would inevitably lead to one's damnation or lead one further astray. But, ultimately, their efforts were of no avail. The older rites not only survived, but such periodic festivities ended up penetrating into the interior of many churches where similar “dramas” and “pageantry” would be played out in a Christian context in late medieval times. The reversal of sacred and profane, the temporary relaxation of secular laws, the overturning of ethical concepts for a time were all presided over by a “Patriarch,” “Pope,” or “Bishop” of Fools.

Finally, the Church decided on a more definitive policy regarding such festivities in many locales. By assimilating some customs around the theme of the ancient concept of the “Feast of Fools” or similar event, such lively pageantry ended up becoming a vital part of medieval Christmas festivities and Yuletide events. In a number of areas, some early chroniclers huffily declared that at times the clergy appeared to enjoy it as much—or more—than the general populace itself.

Some historians and folklorists believe the development of a specific “Patriarch” or a “Lord of Fools” figure (in a reworked Christian context) may have originated in Byzantium, the Eastern Christian empire. Already in the ninth century, the Council of Constantinople strongly condemned what they described as the “profanity” of courtiers who allegedly paraded a mock patriarch and were said to have “burlesqued the divine mysteries.” In the twelfth century, the Patriarch Balsamon attempted to suppress the revels in which the clergy of St. Sophia indulged, especially at Christmas and in early February at Candlemas. So it appears that a version, or versions, of a “Feast of Fools” took place in both East and West.

Outdoor festivities

The theatrical and dramatic activities held at the medieval cathedrals not only took place inside the building, but also took place outdoors. Some religious and cultural scholars maintain this was a first step towards secular theatre. Outdoor liturgical dramas and miracle plays—with their elaborate stage scenery and simultaneous action in Heaven, Earth, and Hell—often took place against the backdrop of a Gothic cathedral, the civic focal point for the community. Lasting for hours and sometimes even days on end, these colorful cycles of theatre and pageantry tended to occur during the summer when the weather was more favorable.

Paris, for example, held many famous medieval pageants, sponsored by the wealthier guilds, in or near its major cathedrals. Such pageants became especially popular with the public. In England, many well-presented, colorful mystery and biblical plays were sponsored by the guilds. These were often performed in June, for the Corpus Christi festival and on other occasions. (21) The major towns that provided Corpus Christi plays were Coventry and York.

Those at Coventry were arguably the most famous and were often visited by royalty. The city's crafts guilds spent lavishly on costumes, musicians, and equipment for these important events for all. The performances were true plays, long and elaborate (probably no more than ten in number), so that only the richest guilds could afford to stage them single-handedly. Only two of these plays have survived the ravages of time.

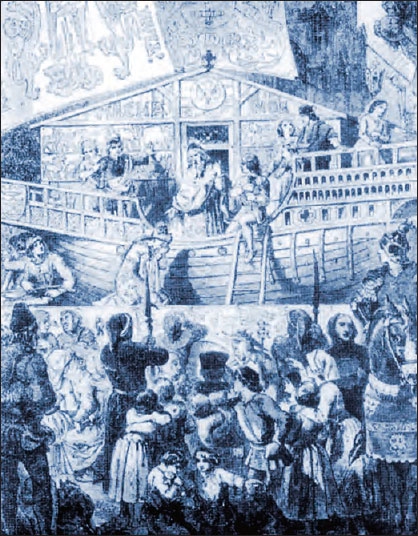

Medieval Noah's Ark guild pageant. (The Brydon Collection)

At York, fifty-two plays were held, each briefer than those at Coventry. This series covered between them the whole of Christian cosmic history from Creation to Doomsday—quite a feat! They were performed on large wheeled wagons—a heavy expenditure for the professional guilds to make and maintain. But maintain them they did, as it allowed them to move their stage plays around according to the cycle of the season's productions. While the texts for most of these plays have survived, it is not known exactly how they were produced, although more scholarly research is now being done in these interdisciplinary areas. Not all cathedral towns would stage a Corpus Christi play. London and Exeter, for instance, preferred to stage plays at the Midsummer Watch rather than Corpus Christi.

MUSIC IN THE CATHEDRAL

A Gothic cathedral would also serve as a concert hall for the community, a place where music was heard, performed, and enjoyed. Images of monks singing gloriously resonant meditative Gregorian chants tend to come to mind today. Yet in the High Middle Ages, instrumental music would also be allowed on some occasions. Some of the most joyous uses of music took place in the setting of a Gothic cathedral. The Feast of Fools, in particular, was an occasion for the combination of medieval drama, minstrels and troubadours, and pageantry. We find numerous images of musicians in the design and stone and wood carvings at many cathedrals. (22)

Readers may be surprised to learn that the organ was not a major instrument in a medieval cathedral's music program. In fact, some cathedrals did not even bother to obtain an organ until later on; it was certainly not seen at the time as the central or primary musical instrument for a cathedral or a church, like it often is today. We will come back to the organ later in this chapter.

However, the study of music was absolutely central in medieval times, as it was one of the four liberal arts that formed the Quadrivium, the medieval curriculum. This is in contrast to our era, where music is usually considered an “extracurricular” or as a merely “elective” activity or only for entertainment, as opposed to more practical course matter. In cathedral schools, especially, practical instruction in music was seen as paramount. The Church's plainsong and other liturgical applications were widespread. Theoretical work on the mathematical basis of music—ultimately harking back to Pythagorean philosophy and other perennial wisdom streams from more ancient times—was an important part of the medieval curriculum.

LEFT: Harp player stone carving, Beverley Minster, England (Dr. Gordon Strachan)

RIGHT: Violin player carving at Beverley Minster, England (Dr. Gordon Strachan)

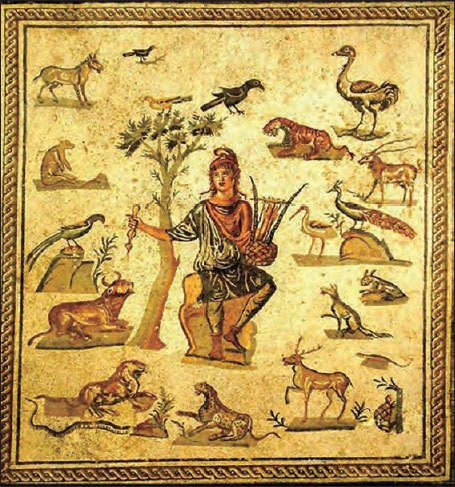

Roman mosaic depicting Orpheus, wearing a Phrygian cap and surrounded by the beasts enchanted by the music of his lyre. He is the archetypal musician, said to have charmed all of Nature and the Heavens with his tunes. (WMC)

The controversy surrounding the introduction of musical harmony

The medieval period saw the development of one of the most important changes in all of Western music history—one which has strongly affected us today—the development of harmony. Simply put, “polyphony” was music that was not monosyllabic, i.e., like a Gregorian chant. Instead, it was more complex with many harmonies interwoven in at the same time, much like hearing a single “chord” rather than merely a single note or tone. For centuries, the mainstream policy of the Church was a clear preference for monosyllabic chanting. The introduction of “polyphonic” music called forth the expression of fierce opinions on either side of the musical and ideological divide.

Traveling troubadours used polyphonic music—introducing the joyous (and “suspect”) major third interval—which assisted in spreading these colorful, new sounds all over Europe. Suddenly, for many, music was not only heard as a “single” note, as it now had many more layers, resulting in a totally new multi-dimensional sound experience to the ear. However, this was not something many in the Church felt was at all proper for solemn religious services. Monosyllabic chants were seen as far more appropriate, both musically and spiritually. As we will see, the introduction of polyphonic vocal music changed the music scene from the simple, pure melodic lines of Gregorian chant. The embracing of full harmonic choirs and sounds was a “revolution” for its time.

A fierce “showdown” over polyphony and harmony: “a chorus of sirens”?

Harmonic music was believed to degrade what churchmen felt to be the purity of the monosyllabic sound of the simple Gregorian chant. It was also felt to corrupt the old Church modes then in use. Polyphony was viewed as highly suspect, “too pagan,” inviting the influx of musical influences and tastes from other areas and cultures, and far too reminiscent of the ancient world. It was too much change from the usual austere, singular sounds of chants that people were used to. Its more complex harmonic sounds were believed by some to have a highly “corruptive” effect on the listener, risking further danger to one's soul.

In the twelfth century, John of Salisbury likened such harmonic singing to a “chorus of sirens.” Pope John XXII, in a bull issued at Avignon in 1324/5, sought to ban almost all polyphony, complaining that the modest plainchant was being obscured by many voices and sounds. Harmony was thought to be, or to invite, “sensuous” and “dangerous” influences—something to be avoided by the devout, especially in a monastic setting. Polyphony was described as “sinful,” music that could lead believers astray, risking eternal damnation. But these medieval “puritans” were not alone. Many before them—including the famous Church father Clement of Alexandria (2nd—3rd century)—had a definite preference for plainchant only, and did not relish being exposed to polyphony. Clement especially wanted to ban chromatic music “with its colorful harmonies ...” (23) commenting in one treatise that, “...we shall choose temperate harmonies... austere and temperate songs protect against wild drunkenness; therefore we shall leave chromatic harmonies to immoderate revels and to the music of courtesans.” (24)

As we can see, in the eyes of polyphony's detractors, there were serious religious, moral, and ethical issues involved with such sounds. Their fierce arguments over musical stylistic choices warned against dangers that could affect the very fate of one's soul. The stakes were high. The longtime controversy over harmonic music came to a head in the Middle Ages, presenting the church with a serious dilemma. After all, some of the best musicians in medieval times were within the Church, highly educated and gifted musicians in their own right. Not all of them were as fearful of the “new” polyphony as others. Some, particularly those who played a psaltery and the vocalists, risked much—even excommunication—if they were caught privately experimenting with harmonic sounds. Whenever they could, however, they worked in secret.

Despite the storms of disapproval of polyphony, its powerful detractors were unable to stem the tide of this musical innovation. So harmony and polyphony became more widely incorporated. From the twelfth century onward, more elaborate forms of music caught on and evolved. In the fourteenth century, the first integrated polyphonic setting of the Mass took place—a medieval “music milestone.”

The “major third” interval

In about the twelfth century, a three-note chord, the triad, was established—the “1-3-5” pattern familiar to musicians today. The three notes of a triad are known as the root, third and fifth. For example, on a piano, these notes could be middle C, E, and G, with the third interval (in this case, E) midway between the root and the fifth. The triad chord was to become the basis of Western harmony based on the natural harmonic series—building on the premise that in nature itself, a single note sets up a harmony of its own. The introduction of the major third interval as part of this triad completely changed the emotional ambience of the church modes then in use.

In 1322, Pope John XXII was so angered by the corrupting sound of the major third that he issued a decree to forbid its use. He felt it secularized the ecclesiastical modes, making it difficult to distinguish between them. (25) As we know, the major third interval was later heavily used in troubadour songs, and is generally thought to be a “joyful” sound to the human ear. Worldwide, ethnomusicologists note that, on the whole, it seems to make people feel “happy.” The major third and the 1-3-5 triad are still used in many popular songs. But with the introduction of accidentals—flats, naturals and sharps—to correct an inherent flaw in the natural harmonic series, there came far-reaching implications.

“Diabolis in musica”—the devil's interval

As is well-known in music theory, the interval of the diminished fifth (or augmented fourth) sounds “incomplete” and “unresolved” to the human ear. One specific interval, the diminished fifth, was greatly feared andshunned, its rather discordant sound believed to be dissonant and imperfect. Even the ancient Greeks acknowledged this interval's negative effect on the human ear. In medieval times, the diminished fifth (augmented fourth) was believed to be “of the devil,” corrupting and highly dangerous, thus dubbed diabolis in musica—the devil's interval.

In the Middle Ages, the first accidental, B-flat, was introduced to help correct what was believed to be the “demonizing effect” of the diminished fifth interval. Many musicologists believe that our tonal system is largely the product of Western Europe's reaction to the inherent “flaw” in the natural harmonic series, and the key-system now in use was partly designed to correct it. As a result, the old Church modes were altered, with the Greek Lydian mode becoming what is now called the key of F-major. This change, too, greatly angered many traditional churchmen at the time. The introduction of the B-flat rather than the usual b-natural completely distorted the natural church mode in their view.

Indeed, the hierarchy of the medieval Church was very well aware of the ancients' beliefs about the power and effects of certain sounds and musical instruments. These educated men had read the ancient Greek philosophers and were familiar with their writings on musical theory. In ancient Greece, certain music—such as that played on the cithara, a stringed instrument similar to a lyre—“was often guarded with religious scruple, and it was punishable by death to change the tuning or the number of strings...” (26) Ancient philosophers highly valued music in spiritual education, and held the belief that a nation which respects music, “and makes the laws of harmony the foundation of all its laws, measures, and philosophy, will be in accord with things as they are in the cosmos.” (27) Plato, for example, wrote in the Republic 401d, “For the soul: Education in music is ‘most sovereign.’” (28)

Others philosophers had similar views, and over time, it became a question of “what type” of music was believed to have a “positive” effects on the soul, and what may be deemed “negative.” Music was recognized as a dangerous art by Plato, Tolstoy, and some of the Church Fathers, all of whom wished at various times to control, limit and confine the uses of certain music. (29)

Musical instruments in church: highly suspect and later forbidden

In the early Christian era, musical instruments were the focus of yet another fierce struggle. As with Gothic design and the “new” harmonic musical style of polyphony, another issue came to the fore for the Church: whether it was proper or appropriate for musical instruments to be played inside a cathedral or church setting. This was heatedly debated.

Medieval Musician from the Luttrell Psalter.

The general feeling was that Christian churches should not host or sponsor so-called “pagan” instruments—especially the flute and the harp—which were often predominant in the ancient Greek festivals, feast days, and in many of their spiritual and other activities. One of the premier instruments of ancient Greece, the lyre-like cithara, was specifically singled out for blame by none other than the learned St. Augustine (354-430 CE). In his second discourse on Psalm 32:33, (Enarratio II in Ps. 32,5), Augustine asks the pointed question: “Has not the institution of those vigils in Christ's name caused the citharas to be banished from this place?” Obviously, the implication was that the cithara was not an instrument deemed appropriate for a religious service in “Christ's name.”

“...if he learns to play the guitar, he shall also be taught to confess it...”

Other musical instruments, in addition to the dreaded flute, harp, and cithara, were also banned in medieval churches, as dangerous “distractions” for the devout or pious. This even included the organ. Ironically, today we think of the organ as a conservative, iconic Church instrument. It may even sometimes seem a little dreary or solemn to some people. But it was initially feared in medieval times due to its bringing in harmonic sounds. As we have seen, harmonic vocal music, and especially any instrumental accompaniments, were believed to be further debasing the “purity” of the old Church modes. New perspectives were not necessarily welcome.

The overall popularity of the use of the organ in church music is definitely a modern-day preference. Today, most churches use an organ as their primary instrument for religious services. Although the organ was present in some medieval cathedrals and displayed in some of their stone carvings, its use was not widespread early on, nor once instituted, was it cherished by all. One famous Abbot, Aelred of Rievaulx, fervently complained, “Why, I pray you, this dreadful blowing which recalls the noise of thunder rather than the sweetness of the human voice?” There is not a single reference to an organ in use at Notre-Dame cathedral in Paris until as late as the fourteenth century—and even then, it was a much smaller instrument than most church organs in use today.

Singing itself was already highly “suspect” in many areas, especially when accompanied by “pagan” musical instruments. Such instruments still enjoyed great popularity with many Europeans, but the Church shunned them. “A cappella,” is an Italian phrase which literally means “in the manner of the church.” Today, it designates singing unaccompanied by musical instruments. As early as the fifth century, the Church's offical attitude toward music was made clear:

Singing of itself is not to be considered as fit only for the unclean, but rather singing to the accompaniment of soulless instruments and dancing... Therefore the use of such instruments with singing in church music must be shunned... Simple singing alone remains... If a lector learns to play the guitar, he shall also be taught to confess it. If he does not return to it, he shall suffer his penance for seven weeks. If he keeps at it, he shall be excommunicated and put out of the church. (30)

Obviously, such views, even from early on in the Church's history, demonstrate a definite concern by the hierarchy to protect ecclesiastical singing from every kind of instrumental music. Even in the earlier centuries of the church's history, the playing of certain musical instruments inside a church was often a highly contentious issue. By the High Middle Ages, as we know, the troubadours in particular began to use and promote the major third interval and experiment with other creative musical styles, at times risking their lives in the process; such creativity came at a price, however, for they, too, eventually became targets—i.e, musical “heretics”—of the Inquisition, especially in the Languedoc.

In my earlier work, entitled Medieval Mysteries, there is a chapter on the history of the medieval troubadours in the High Middle Ages period, including information about how they, too, were eventually targeted by the Inquisition:

The Knights Templar, Cathars, Sufis and similar groups liaised with troubadours, contributing to the overall flowering of the troubadour movement at its peak. Yet, in time, the culture, language and music of the troubadours were wiped out by a combination of the Inquisition and the Bubonic Plague. By the 14th century, in Toulouse, the mere possession of a troubadour manuscript was enough to land one before the terrible tribunals of the Inquisition. Of the Occitan troubadours, only a few hundred sparse melodic frames have survived...Europe lost a great treasure when the last troubadour died in 1292. He was Guiraud Riquier of Narbonne (1254-92). But by the time he reached maturity, the art was already failing. The Inquisition targeted the trouabadours and worked feverishly to suppress them... (31)

Even in modern times, debate still goes on in certain locales whether to allow the use of different instruments within a cathedral or church, and, if so, at what times, and under what circumstances—“echoes” of the various debates in the medieval era and earlier centuries about music.

There is little doubt that vocal music predominated in medieval Gothic cathedral services and activities. Despite a widespread rejection of certain music by puritanical clerics, the late Middle Ages is known for a triumphant flowering of its vocal music. As we've discussed, there were the popular feast days at which lively, raucous, bawdy songs were sung by all, as medieval music ranged at those times from the seriously solemn to the wildly festive.

Sacred music is deeply associated with spiritual and religious experience. In more recent eras, the German poet Goethe and others have referred to the concept of architecture as “frozen music.” In other words, they associate the use of sacred space with sound. (In the traditional Hermetic Qabalah, sound is associated with Spirit.) Thus, in the Renaissance, “they often proportioned rooms according to musical chords so that when you were walking into a building, you were really walking into, as they called it, a piece of frozen music. So there was a harmony with universal structures, and then also with human structures,” comments modern American architect Anthony Lawlor. (32)

LEFT: Organetto instrument, as portrayed on the stone carving at Beverley Minster, England (Dr Gordon Strachan)

RIGHT: Organ-like instrument, similar to a medieval hurdy gurdy, portrayed in a stone carving at Beverley Minster, England (Dr Gordon Strachan)

In western Europe, musicologists note that we can largely thank the late medieval era for the polyphony and harmony we hear in our favorite music today, popular and otherwise. And, of course, we should also still pay tribute today for the courageous efforts of the medieval troubadours and other musicians for daring to introduce new styles and traditions, often against great, even life-threatening, odds.

In spite of numerous efforts to suppress it, polyphony and beautiful harmonies nevertheless survived—both within the Church and without—and in both vocal music as well as instrumental. The exquisite Notre Dame cathedral plays a key role here in music history, for it is a fact that “the music composed for the liturgy at the new cathedral of Notre-Dame became the first international repertory of harmonized music. It spread throughout Europe and served as the foundation and inspiration for the next century's developments, from which a clear line can be traced to the more familiar music, popular and classical alike, whose harmonic nature everyone takes for granted.” (33)

Thus, despite the reluctance of the Church to adapt, music too, became a key part of the experience of a Gothic cathedral. Medieval cathedral visitors and pilgrims would see the colorful influx of light from the bright stained glass windows; appreciate the architectural unity of the cathedral building and grounds; and hear the inspiring music of the choir, sometimes accompanied by musical instruments. This sensory environment resulted in what many today find to be a beautiful and aesthetic way to spend a day when in a major European city.

In contrast to the Romanesque Abbey—often located in a deliberately isolated and remote location—the centrally located Gothic cathedral was the main focal point of a medieval town. It was an expression of a newly emerging civic consciousness—a result of the rapid growth of medieval towns—providing a focus of artistic and intellectual life in addition to religious services. The cathedral schools, typified by Chartres, were one of the foundations out of which universities would later grow.

The buildings themselves provided the focus for the display of an often high level of artistic skill and accomplished sophisticated craftsmanship. Such artistic, scientific, and engineering advances helped to celebrate the knowledge, philosophy of beauty, and aesthetic experience at the peak of the great “age of the cathedral.”

One of the most important crafts in the development of Gothic architecture was stonemasonry, to which we will now turn. Who were these gifted stonemasons?